By Bram Peters, Food Systems Programme Facilitator

The future is a mystery, full of uncertainties, risks and opportunities. Yet, humans and human systems have a remarkable ability to turn imagination into reality. In this landscape of uncertainty, foresight becomes an essential tool, helping us navigate what lies in the future. This is especially important when it comes to food systems transformation.

In this blog, I will endeavour to give you a glimpse at how foresight, awareness of the political nature of futures, and alternative scenarios can help us rethink and reshape our food systems for a more just and sustainable future.

Four Ways to Think About the Future

According to Muiderman et al. (2020), there are four main approaches to foresight:

- Assessing Probable (and Improbable) Futures

Example: The IPCC climate scenarios, which predict likely outcomes based on different climatic and environmental trends, and possible climate actions. - Contending with Multiple Plausible Futures

Example: Scenario matrices that explore what could happen in different situations under various combinations of uncertainties. - Imagining Diverse, Pluralistic Futures

Example: Visioning exercises where we picture a desired future, then work backwards (backcasting) to figure out how to get there. - Scrutinizing the Performative Power of Future Imaginaries

This approach examines how our collective visions of the future can actually shape reality.

Most foresight work focuses on the first three approaches. But in today’s world, shaped by pandemics, global conflicts, and rising political tensions, having the skills to apply the fourth approach can be considered to be more important than ever. A recent Synthesis Review of food system futures conducted by Foresight4Food identified that we can generally see various clusters of key food systems futures around ‘business as usual’, ‘global sustainability’,

‘local solutions’, ‘rising inequalities’, and ‘uncontrolled chaos’. However, it was also observed that none of these described scenarios portray very radically different food system futures.

The Power of Collective Imagination

Jasanoff and Kim, in their book Dreamscapes of Modernity (2015), introduce the idea of socio-technical imaginaries:

“Collectively imagined forms of social life and social order reflected in the design and fulfilment of nation-specific scientific and/or technological projects.”

In simpler terms, societies tell themselves stories about who they are, where they’ve been, and where they’re going. These stories—these imaginaries— can reshape history, redefine the present, and chart a course for the future. And often, they serve the interests of those in power.

The Future Is Political—and It’s Already Here

Why does this matter? Because the future isn’t just something that happens to us. It’s something that societies seek to actively shape, often through powerful narratives. Consider some current, concerning, imaginaries being promoted by powerful elites:

- Trump’s “Golden Dome” and the slogan “Make America Great Again”

- Elon Musk and other tech company elites’ visions of Artificial General Intelligence

Alternative imaginaries to counter power and transform societies toward a very different future also exist. Think about:

- The Degrowth Manifesto, as proposed by Kohei Saito in his book ‘Slow Down’

- Ministry of the Future, as narrated by Kim Stanley Robinson

Shaping Better Futures—Together

Foresight, when used critically, inclusively and deliberatively, has the power to shape more inclusive and constructive imaginaries. Jasanoff writes that these imaginaries “offers a glimpse into the realities of the known, the made, the remembered, and the desired worlds in which we live—and which we have the power to refashion through our creative, collective imaginings.”

In other words, we can—and should— together imagine alternative, inclusive, sustainable and transformative futures, making them tangible. The time to do this, at scale, is now. The Foresight4Food Global Workshop, taking place in Jordan from 15-19 June, will include an exercise on ‘Radical Food System Futures’. This will harness the collective intelligence of the foresight and food systems community, and enhance focus on imagining very different food systems than we see around us today.

By Bhawana Gupta and Monika Zurek

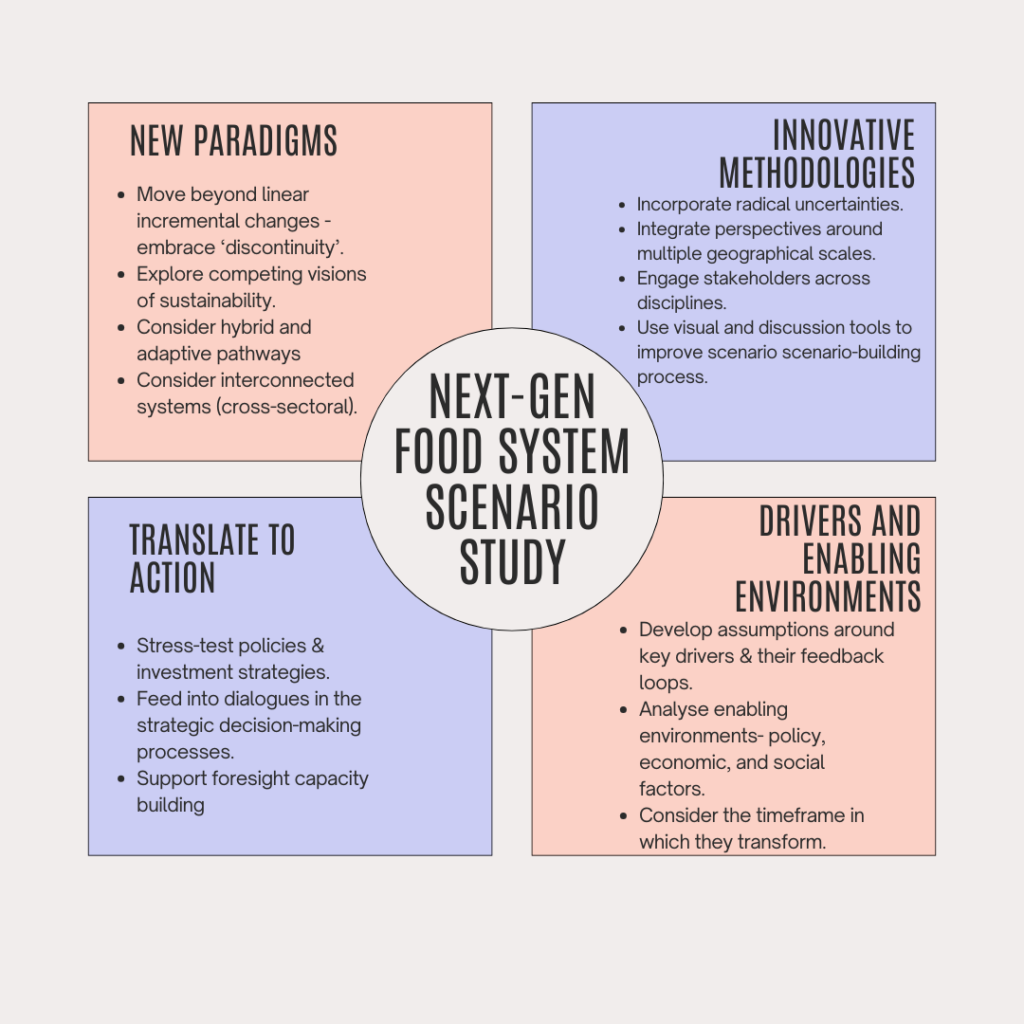

What if the future of our food system looks nothing like what we’ve imagined so far? Our recent report “Food systems of the future” examines how foresight studies are shaping our view of what’s to come. It reveals the urgent need for a new wave of forward-thinking work that dares to imagine fundamentally different food system configurations. Next-generation food system scenarios must embrace a new change paradigm, innovative methodologies, and a clear pathway to incentivise action through a deeper understanding of future drivers and enabling environments.

Why do we need another global-level scenario study?

We live in what many call the acceleration phase of the Anthropocene, an era defined by rapid and unpredictable change. For years, scholars and practitioners across disciplines worked to unravel the complexities of our global food system, using scenarios as vital tools to explore how different forces shape its future. But it’s crucial to remember that these scenarios are not only built on data; our assumptions, beliefs also shape them, and our constantly evolving grasp of the drivers of change[i].

The evolution of food system scenarios reflects this shift. Early models mostly focused on projecting food production and demand based on population growth. Over time, their scope broadened to encompass factors like resource availability, climate change, policy shifts, and socio-economic dynamics. Yet, the turbulent events of the past five years—think of the global pandemic, geopolitical tension, and unexpected supply chain disruption—have shown us that even the most sophisticated scenarios failed to capture certain uncertainties.

Grappling with the multifaceted complexities of the future is undoubtedly a wicked problem. But by continually refining our foresight techniques, we can better prepare for future shocks and proactively design alternative pathways. Let’s explore the critical building blocks for this next generation of global food system scenarios.

1. New paradigms

In Donella Meadows’ view, a paradigm is a shared set of beliefs, values, and assumptions that underlie a system. This core mindset dictates the system’s goals, structures, and operational rules. It follows that a paradigm shift is one of the most powerful drivers of lasting change within a system. For our discussion, there are three aspects that should be considered:

- Discontinuity: Past scenario studies often urged the inclusion of a surprise element or discontinuity[ii] (read box 1 for definition). However, these discontinuities were considered weak in almost all scenarios, especially quantified ones. Instead, scenario studies emphasised continuous incremental changes in the system. Going forward, our scenarios must move beyond a smooth and predictable evolution to explicitly explore non-linear changes, tipping points, and abrupt shifts.

BOX- 1

The term discontinuity is used variously in scenario literature, broadly signifying a sharp departure from past trends caused by high-impact developments, phenomena, and events. The significance of a discontinuity depends on its character, magnitude, speed, and ripple effects, and whether it has been anticipated and ameliorated. Here, a discontinuity refers to a significant shift of social-ecological structure and dynamics, rather than a transient perturbation after which the system reverts to its original trajectory. Related terms are surprises, bifurcation, critical transition, tipping points, tipping elements, wild cards, and black swan events. More recently, the phrase game changers has been introduced for shifts in how society is organized through understandings, values, institutions, and social relationships.

- Mental models: Since the IPCC’s ‘Shared Socio-economic Pathways’, most global scenario studies have relied on a mental model that assumes four broad pathways:

- A sustainable pathway characterised by progressive policy and technological adoption.

- A business-as-usual pathway, projecting a continuation of current trends.

- A collapse or environmental destruction pathway, depicting worst-case outcomes.

- A divided world pathway, where inequalities worsen and cause socioeconomic distress.

While seemingly intuitive the widespread use of this mental model is influenced by cultural biases, cognitive processes[iii], and the culture of scientific reticence[iv] (read box 2 for more). These factors can lead to the design of scenarios that are overly simple, feel intuitively right, and align with common ways of thinking about the future: an optimistic view, a middle ground, and a pessimistic view. We must challenge this reliance on simplistic archetypes and embrace more nuanced and multi-dimensional perspectives in our scenario development.

BOX- 2

Anchoring bias: We tend to rely too heavily on initial information, making it difficult to envision radically different futures.

Confirmation bias: We seek out information that confirms our existing beliefs, reinforcing the status quo.

Incrementalism: We assume change will be gradual and predictable, neglecting the potential for sudden, non-linear shifts.

Lack of interdisciplinary input: Many scenario studies are limited by the perspectives of a narrow range of experts, missing crucial insights from other fields like sociology, ecology, and complexity science.

- Cross-sectoral linkages: Too often, scenario studies operate in isolation, focussing on a single system like food. They fail to incorporate the strong interdependencies with other critical systems such as energy, water, or social systems. This approach can create a lack of understanding of the potential for cascading system failures, or conversely, unexpected positive feedback loops. Future scenarios must explicitly model these intricate interconnections, exploring how changes in one sector can trigger ripple effects across others.

2. Innovative methodologies

Advancing food system scenarios requires leveraging innovative methodologies, for example:

- Multi-scale analysis: Most past food system scenario studies focused on processes at specific geographic scales. Yet food systems operate across a spectrum, from individual households to global markets, with numerous complex inter-dependencies. These dynamics need to be captured in the future studies. The methodology for linking scenarios at different scales was explored by Zurek et al[v]. By integrating local, regional, and global food system dynamics, we gain a more holistic understanding of potential futures.

- Radical scenario development: The scenarios developed in the last decade have often underplayed outlying, surprise, or disaster events[vi]. Yet the inclusion of diverse and radical uncertainties can advance the quality and utility of scenarios[vii]. The development of radical scenarios combines established scenarios with group discussion techniques, as discussed in Talwar et al.[viii]. We need to better embrace wild cards and black swans as integral parts of scenario development, exploring how low-probability, high-impact events can reshape the future.

- Multi-disciplinary expert involvement: Food systems are inherently complex and interconnected, necessitating the involvement of actors across multiple sectors (e.g., agriculture, trade, health, and environment) and governance levels (from local to global). Innovative participatory methodologies such as Transdisciplinary Foresight Labs[ix] and Causal Layered Analysis (CLA)[x] can unpack issues on various levels and uncover underlying assumptions around litany, systemic causes, worldviews, and myths that shape expert opinions. Together, these methodologies support more holistic, inclusive, and imaginative scenario processes.

3. Drivers and enabling environments

Today’s scenarios commonly describe assumptions around the drivers of change (e.g. technological shifts, demand patterns, and trade dynamics). Next-generation studies must go further and reflect on the enabling environments that shape the dynamics of future food system drivers and the timeframe within which the change unfolds. This includes[xi]:

- Policy and governance: How do regulations, institutional capacity, and international agreements shape food system operations?

- Economic and financial structures: How do investment patterns, trade dynamics, and economic inequality influence food access and production?

- Social and cultural context: How do changing consumer preferences, social equity, and cultural norms drive food demand and system practices?

- Technological and infrastructural frameworks: How does digital connectivity, research and development (R&D), and infrastructure development enable or constrain food system innovation?

- Environmental governance: How do policies and practices regarding resource management and climate change impact food production sustainability?

4. Translate to action

Developing next-generation scenarios is not just an academic exercise. To be truly impactful, these studies must bridge the gap between foresight and implementation, ensuring that scenario narratives translate into policy and strategic actions. This involves:

- Using real-world stress tests: Running policies and investment strategies against multiple scenario conditions to assess their resilience.

- Embedding scenario thinking: Integrating foresight and scenario planning directly into decision-making processes at national and global levels. (Read about institutionalising foresight in decision-making in another blog).

- Engaging non-traditional stakeholders: Involving a broader range of voices, including grassroots organizations, indigenous groups, and regenerative farmers, to develop a shared language around food systems and future pathways.

Conclusion

Essentially, the prevailing paradigm in many current scenario studies inadvertently restricts our imagination and limits our collective ability to envision and prepare for truly transformative change. It creates an illusion of control in a world that is far more contingent and unpredictable. The necessary shift towards scenario studies that adequately reflect paradigm shifts is a complex but crucial endeavour, requiring a fundamental rethinking of how we construct and interpret future possibilities.

The food system of tomorrow will not be shaped by predictions, but by our collective capacity to anticipate, adapt, and transform. Advancing next-generation global food system scenarios requires bold thinking, cross-sector collaboration, and an openness to radical possibilities. The question remains: are we ready to embrace this challenge?

[i] Cork, S., Alexandra, C., Alvarez-Romero, J.G., Bennett, E.M., Berbés-Blázquez, M., Bohensky, E., Bok, B., Costanza, R., Hashimoto, S., Hill, R. and Inayatullah, S., 2023. Exploring alternative futures in the Anthropocene. Annual Review of Environment and Resources, 48(1), pp.25-54.

[ii] Rothman, D.S., Raskin, P., Kok, K., Robinson, J., Jäger, J., Hughes, B. and Sutton, P.C., 2023. Global Discontinuity: Time for a Paradigm Shift in Global Scenario Analysis. Sustainability, 15(17), p.12950.

[iii] Cork, S., Alexandra, C., Alvarez-Romero, J.G., Bennett, E.M., Berbés-Blázquez, M., Bohensky, E., Bok, B., Costanza, R., Hashimoto, S., Hill, R. and Inayatullah, S., 2023. Exploring alternative futures in the Anthropocene. Annual Review of Environment and Resources, 48(1), pp.25-54.

[iv] Rothman, D.S., Raskin, P., Kok, K., Robinson, J., Jäger, J., Hughes, B. and Sutton, P.C., 2023. Global Discontinuity: Time for a Paradigm Shift in Global Scenario Analysis. Sustainability, 15(17), p.12950.

[v] Zurek, M.B. and Henrichs, T., 2007. Linking scenarios across geographical scales in international environmental assessments. Technological forecasting and social change, 74(8), pp.1282-1295.

[vi] Gupta, B., Zurek, M.B., Woodhill, J. and Ingram, J. 2025 submitted for publication to Frontiers in Sustainable food systems

[vii] Gordon, D., 2021. Radical Uncertainty: Decision-Making Beyond the Numbers. Quarterly Journal of Austrian Economics, 24(1), pp.206-210.

[viii] https://jfsdigital.org/2019/06/15/the-future-of-energy-reinvented-case-study-of-the-radical-scenario-development-approach/

[ix] Pólvora, A. and Nascimento, S., 2021. Foresight and design fictions meet at a policy lab: An experimentation approach in public sector innovation. Futures, 128, p.102709.

[x] UNDP (2022). UNDP RBAP: Foresight Playbook. New York, New York.

[xi] Gupta, B., Zurek, M., Woodhill, J., Ingram, J. (January, 2025). Food Systems of the Future: A synthesis of food system drivers and recent scenario studies. Foresight4Food. Oxford, United Kingdom.

The Foresight for Food System Transformation (FoSTr) programme, led by Foresight4Food, is now two years into its journey of helping shape more sustainable, inclusive, and resilient food systems. With increasing uncertainties affecting global food systems—from climate change to economic challenges—the need for foresight and scenario analysis has never been more critical.

Running from 2022 to 2025, the programme is funded by the Dutch Ministry of Foreign Affairs through an IFAD grant. Based on the approach of the Foresight Framework, the programme focuses on supporting four key countries: Bangladesh, Jordan, Kenya, and Uganda.

Since its commencement, we have seen tremendous strides in advancing the key objectives of the FoSTr programme across multiple fronts. This blog highlights the progress and impact of the FoSTr programme and the exciting path ahead.

In-Country Impact: Strengthening Foresight Processes

In each of the focus countries, national foresight processes gained momentum, engaging a wide range of stakeholders, including government bodies, research institutions, and community representatives. In total, 403 individual stakeholders participated in in-country workshops across the four countries, contributing to meaningful conversations about the future of food systems.

Here is a quick overview of FoSTr programme’s progress in each of the focus countries:

Bangladesh – Strong government buy-in has been established, with collaboration from the Ministry of Food and other key players, all contributing to the national food system transformation agenda.

Jordan – Partnerships with the Ministry of Agriculture and other government entities have positioned FoSTr as a key advisor, particularly in driving forward the work of the newly established Food Security Council.

Kenya – Foresight analysis has been particularly active at both the national and county levels, with significant involvement from the Nakuru and Marsabit County governments.

Uganda – FoSTr is closely aligned with the Uganda Planning Authority, helping develop foresight tools for future food system planning.

Global Collaboration: Building a Brokering Hub

On a global scale, FoSTr expanded its network of foresight and food systems practitioners, deepening collaboration across organizations like the Forum for Agricultural Research in Africa (FARA), the Global Alliance for Improved Nutrition (GAIN) in Bangladesh, and a number of renowned research institutes in the focus countries.

The work of FoSTr programme was very well-received at the 4th Global Foresight4Food Workshop in Dhaka, where more than 120 foresight practitioners from Asia, Africa, and Europe gathered to share insights on foresight methodologies and food system challenges.

Read also:

Using Foresight to Re-imagine the Future of Food Systems: Foresight4Food holds its 4th Global Meeting – by Jim Woodhill

In a highly interactive week, participants engaged in a masterclass on foresight approaches, shared their experiences and lessons, heard from thought-leaders on food systems and foresight, and identified ways of strengthening foresight practice in their own countries and regions…

A Start to the Foresight Process: Food Systems Maps

As a part of the foresight process, there is a need to have a collective understanding of the food system in different contexts. Hence, the Foresight4Food FoSTr team in collaboration with our facilitators and research partners in each focus country, created comprehensive food systems reports mapping the dynamics, trends, drivers, and activities within the food system.

These Food System Maps offer an initial snapshot of the current food system status in the focus countries and are intended to inform a more comprehensive foresight process. As the dynamics, trends, drivers, and activities within the food system continually change, these reports welcome ongoing reflection and discussion.

Knowledge Base

FoSTr also played a vital part in strengthening the Foresight4Food Resource Portal, which provides access to Foresight Studies, key data around Food System Drivers and Outcomes, a database of Foresight Initiatives, and other academic literature that helps food systems practitioners develop better Foresight Models.

The Foresight4Food Resource Portal is regularly updated with the latest research and emerging studies as well as products and resources that come out of different programme activities.

Read also:

The Complexity of Global Drivers of Food System Transformation – by Bhawana Gupta

The global food system needs to be transformed. It needs to deliver better health and improved livelihoods while protecting the environment and minimizing negative social impacts. However, there are many interconnected factors playing a role. Food Systems are complex…

Overcoming Challenges

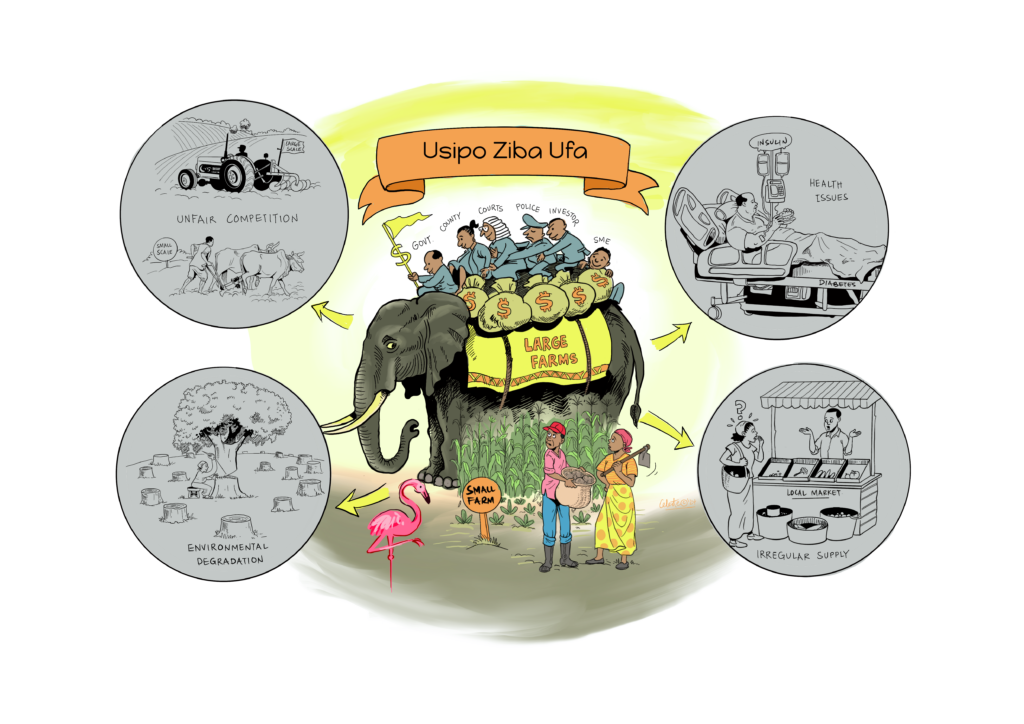

Like any ambitious programme, FoSTr encountered its share of challenges. These included navigating political instability in some focus countries. Meanwhile, navigating the political economy of food systems—especially where entrenched power dynamics and vested interests are at play—required FoSTr to strike a delicate balance between supporting ongoing policy processes and introducing more transformative ideas for change.

The Way Forward

As the Foresight4Food FoSTr programme enters its third and final year, several key objectives will guide the remaining activities:

Brokering Foresight Processes: Continue to build connections with national stakeholders and existing initiatives, ensuring that foresight insights are integrated into policy-making and planning processes.

Capacity Building: Organize intensive face-to-face training workshops to further enhance foresight facilitation skills and broaden participation from underrepresented groups, including the private sector and youth.

Scenario Analysis and Policy Recommendations: Complete the ongoing scenario analyses and translate these into clear policy recommendations that will guide national food system transformation agendas.

Sustaining Momentum Beyond 2025: Establish sustainable communities of practice that can continue to drive foresight activities beyond the programme’s official end.

Conclusion: A Transformative Journey

In an era where global food systems are under immense pressure due to climate change, population growth, and shifting socio-economic landscapes, forward-thinking approaches are critical to ensuring food security and sustainability.

The Foresight4Food FoSTr programme has made significant headway in its mission to advance food system foresight processes in Bangladesh, Jordan, Kenya, and Uganda while building a broader global network of foresight practitioners. As we look ahead to the final year, the focus will be on translating foresight insights into action, empowering national stakeholders, and ensuring that the work of FoSTr continues to have a lasting impact on food systems worldwide.

Bonus: FoSTr Facilitators Insights

As the Foresight4Food FoSTr programme continues to foster systemic change in global food systems, the programme facilitators will be sharing their observations on the work and progress of FoSTr programme in their respective countries through insightful blogs. Watch this space and our social media channels for more updates.

By Bram Peters

The Foresight4Food FoSTr team has just returned from an active and productive trip to Kenya, despite the challenging political situation in the country. From our perspective, this highlights the need to adapt to turbulence and to use foresight to build resilience for Kenya’s food system.

From June 19 to 26, together with my team members including Jim Woodhill, Herman Brouwer, and Wangeci Gitata-Kiriga we conducted a range of food systems foresight workshops in Nairobi and Nakuru with a wide range of national food systems stakeholders. Here is a brief update on the action.

Navigating turbulence

On the morning of June 19, Foresight4Food, together with partners ILRI–CGIAR, Results for Africa Initiative and University of Nairobi, organised two sessions in Nairobi. The interactive breakfast session was all about ‘Navigating agri-business in turbulent futures’. The session was co-hosted by IFAD Kenya and was attended by a range of private sector associations, business support services, innovation facilitators and impact investors.

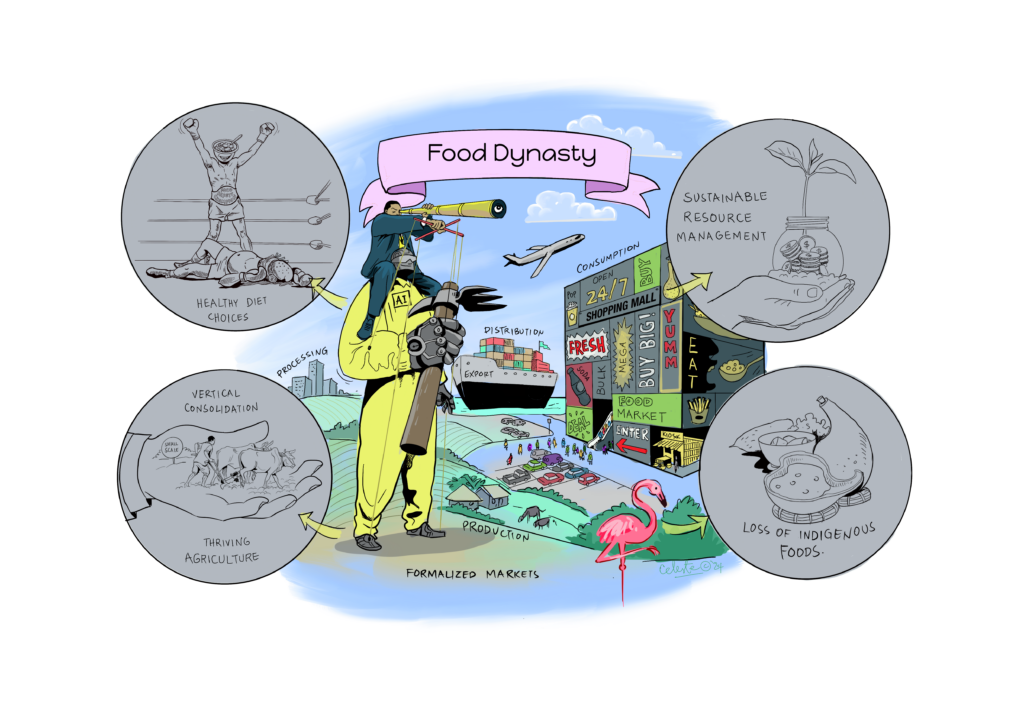

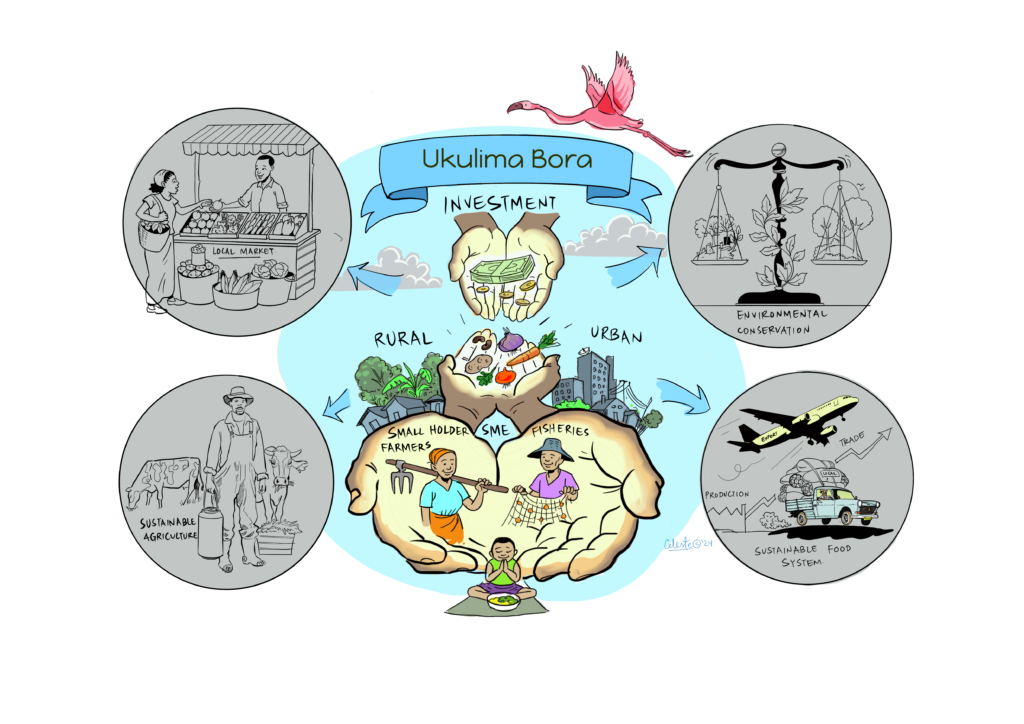

The focus of the meeting was to introduce the topic of foresight in relation to agribusiness in Kenya, share some of the scenarios that were developed in the context of Nakuru, and discuss the implications of different futures of the food system. Participants were shown five different scenarios of how the food system might look in 2040 in Nakuru and were invited to think through and discuss the implications of these scenarios.

With a strong presence and involvement of leaders from various private sector associations such as the Agriculture Sector Network (ASNET) of the Kenya Private Sector Alliance, the discussion invited stakeholders to reflect not only on trends and uncertainties emerging in Kenya, but also how their own businesses are preparing for the future.

Supporting the pathways for food system transformation

In the afternoon of June 19, the FoSTr team organised a national update session on the progress of FoSTr since June 2023. The session was attended by many individuals from the morning session, as well as representatives from government, civil society and research organisations. The FoSTr team presented the latest updates, including the launch of a ‘Kenya Food Systems Mapping Report’, and with a collection of scenarios for the Nakuru food system.

With a special presentation by the Ministry of Agriculture and the Food Systems Technical Working Group and special remarks from IFAD on the 3FS tool, it was discussed how a wide range of ecosystem support initiatives are buttressing the national food systems transformation pathways in Kenya. The approach by Foresight4Food to engage with two counties, Nakuru and Marsabit, and to build on Bottom-up initiatives showed how our approach complements the ongoing national-level initiatives.

Systemic Theory of Change

From June 19 to 21, the Foresight4Food FoSTr team facilitated a 3-day workshop for the inception phase of the new Netherlands-funded, World Food Programme and UNESCO on ‘Sustainably Unlocking the Potential of Lake Turkana. Stakeholder representatives from the Lake Turkana region (both on the Marsabit and Turkana sides of the lake) gathered in Nairobi to engage in a shared analysis of the complex food system and co-create the high-level focus of the programme.

The Turkana Lake food system is highly complex, with high food insecurity, vulnerability to climate change and conflict, and many cultural dynamics around pastoralist and fisheries livelihoods. Finding market opportunities and strengthening resilience is not easy, and requires a different way of working. Using the Foresight4Food approach, and building on 6 scenarios that were developed in previous workshops in Marsabit and Turkana, stakeholders explored what might need to be done to understand systemic risks and how lasting opportunities can be triggered.

Preparing a Systemic ToC is all about analysing the context, articulating the transformations needed in light of various future scenarios, and developing the building blocks for action. The building blocks include pathways, processes and partnerships. Through many interactive discussions and exercises, the stakeholders conducted value chain mapping of the fish value chain, CATWOVE for articulating systemic change narratives, and Causal Loop Mapping.

Manifesto for Change for the Nakuru Food System

On June 24 and 25, the FoSTr team including partners ILRI-CGIAR, Results for Africa Initiative and University of Nairobi once again visited Nakuru, now to explore systemic change pathways. As we already noted from previous workshops, the food system of Nakuru County is full of potential, as Nakuru’s natural resources are rich and a wide range of agricultural value chains are represented. However, challenges related to food and nutrition security and environmental sustainability exist. Trends of climate change, unhealthy diets and land fragmentation are appearing. The future holds many uncertainties. In order to future-proof the food system, it is urgent that investments are made to further enhance the resilience and sustainability of food and agriculture in Nakuru.

Since November 2023, a diverse group of more than 40 different stakeholders from Nakuru county have been coming together to consider the future of food system, supported by researchers and facilitators of Foresight4Food. This inclusive group looked at the challenges and opportunities for food and agriculture today and how they might evolve in 10-15 years. Food system analysis, an assessment of drivers and trends relevant to Nakuru, and 5 scenarios were developed by this group.

During these two days, stakeholders from Nakuru engaged in scenario interpretation and Causal Loop diagramming to come up with key pathways to kickstart food system transformation in Nakuru. These outputs culminated in a Manifesto for Change: a vision for the desired future for Nakuru’s food system and a range of possible pathways that can set us in that direction, while preparing us for a range of uncertainties. The Manifesto calls upon all stakeholders to join and align their actions, and intensify collaboration to transform Nakuru’s food system so that it can feed its people nutritiously; advance economic development; restore balance with nature; grow in-county revenue and eventually GDP growth for Kenya.

by Bram Peters

As a part of the FoSTr programme, the Foresight4Food team organized the “Exploring Alternative Futures for Jordan’s Food System” workshop in Amman, Jordan that brought together food systems stakeholders in Amman to discuss the future of Jordan’s food security. Here are some of the observations and insights from the event.

With themes of resilience, adaptation, action, and collaboration, participants engaged in scenario planning and back-casting exercises to anticipate challenges and shape future outcomes. Key uncertainties like water availability, healthy diets, regional trade, and business structures were explored through four scenarios set in 2040. These insights, supported by quantitative modeling, fostered rich discussions about desirable futures and the actions needed today to create a sustainable, resilient food system for Jordan.

During the workshop, colleagues from the University of Jordan and Jordan University of Science and Technology presented four policy briefs. These were: Food Loss and Waste, Water-to-Food Conversion, State of Smallholder Farming in Jordan and Malnutrition. Each policy brief captures the state of knowledge and offers recommendations to explore how to address these issues from a food systems perspective.

The FoSTr team introduced four critical uncertainties that will be highly important and uncertain to the long-term future of the Jordan food system:

- The extent of fresh water available to agriculture

- The extent to which healthy diets are adopted

- Level of ease of regional trade

- The type of business structure the food system will have

Each of these uncertainties was combined to offer four scenarios, taking place in 2040, up for discussion with the participants. Supported by insights from quantitative simulation modelling, the implications on food systems outcomes were explored in each scenario. Some scenarios described that the people of Jordan adopt healthy diets despite a challenging regional trade situation. In others, severe limitations on fresh water for agriculture were seen in combination with a highly corporate-led food system.

Additionally, the participants explored how that situation might look in each. These scenarios served to open up minds towards the possibility of different situations emerging in the future and highlight the need for anticipatory action and systemic change.

The scenarios led to a discussion of what might be the ‘most likely‘ and ‘most desirable’ scenarios for the Jordan food systems stakeholders. The outline of a desirable future, informed by trends and uncertainties, was formulated to serve as a guiding star. A back-casting approach was used to then explore what events and turning points might occur between 2040 and now to realise that desired future. Based on this timeline, stakeholders brainstormed a range of different actions and stakeholders which are needed now, to already start pushing the system towards the Desired Future.

Building on the encouraging shared co-ownership of the results of the workshop, the Foresight4Food FoSTr team will continue efforts to develop policy briefs, deepen the action areas that were developed, and support the Food Security Council of Jordan in proving the underpinnings for the ongoing work on national food systems transformation.

FAO’s new insightful scenarios for the future of food systems

By Bram Peters, Foresight4Food Global Facilitator

What drivers can trigger food systems transformation? How can we move beyond business as usual in the face of rising food insecurity, environmental degradation and economic instability? The good news is that we can shape food systems to be more resilient and sustainable. The challenge: trading off short-term benefits in search of longer-term outcomes. FAO developed four future scenarios that explore that explore these questions and how we can navigate such paths.

End of 2022, the United Nations Food and Agriculture Organisation (FAO) published the report ‘The Future of Food and Agriculture – Drivers and triggers for transformation’. The key triggers and drivers for transformation are identified based on a diverse and wide range of literature and expert knowledge and then applied to four scenarios to achieve the FAO goal of ‘Four Betters’: better production, better nutrition, better environment and better life. Trade-offs over time and the key use of policy triggers are at the centre of the report’s conclusions. This blog dives into these drivers and futures, and delves into the key implications of this report.

In Search of ‘Four Betters’

FAO strives for ‘Four Betters’: better production, better nutrition, better environment and better life. How to achieve such a vision, and how will this look in the future?Much depends on how drivers play out, how stakeholders tackle trade-offs, and how certain triggers are turned into policy options and implemented. The recent report makes clear that the historical development paths followed by high-income countries, drawing from hegemonic power, colonial wealth and unsustainable practices, are impossible for current low- and middle-income countries to follow. This requires a mindset shift regarding taking responsibility, sharing burdens and investing in a new type of focus on the long-term objective.

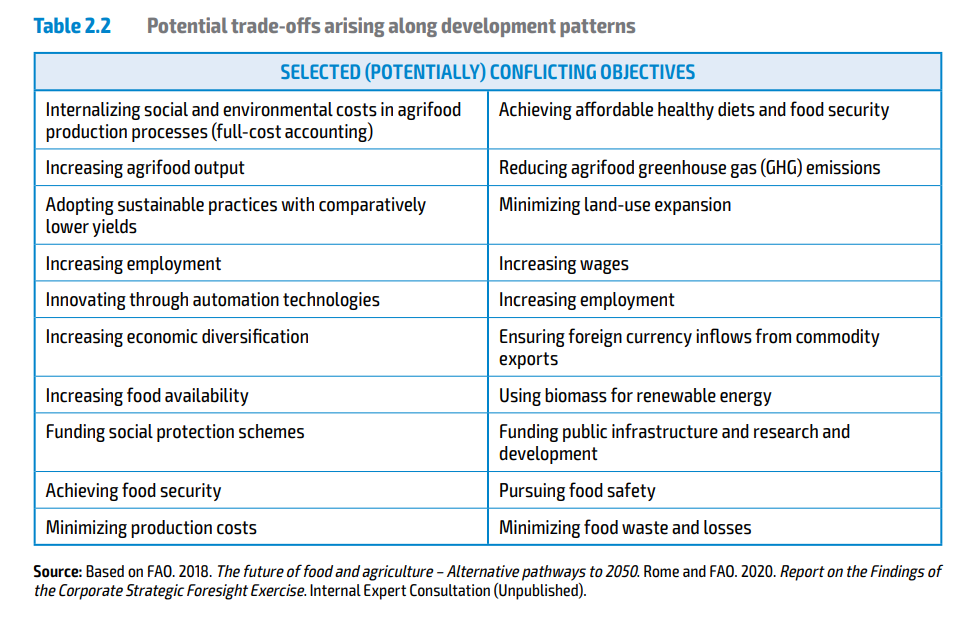

Difficult-to-navigate trade-offs and choices include:

- Short-term productivity gains against greater sustainability and reduced climate impact; “Better production starts from better, critical and informed consumption, but producing more with less will also be unavoidable”.

- Efficiency against inclusiveness; for instance, “technological innovations are part of the solution – provided new technologies and approaches are also accessible to the more vulnerable”.

- Short-term economic growth and well-being against greater long-term resilience and sustainability. In concrete terms, this means “selling the message that well-off people have to lose out economically in the short run, in order to reap environmental benefits and resilience for all in the medium and long term is counterintuitive in this short-termism era”.

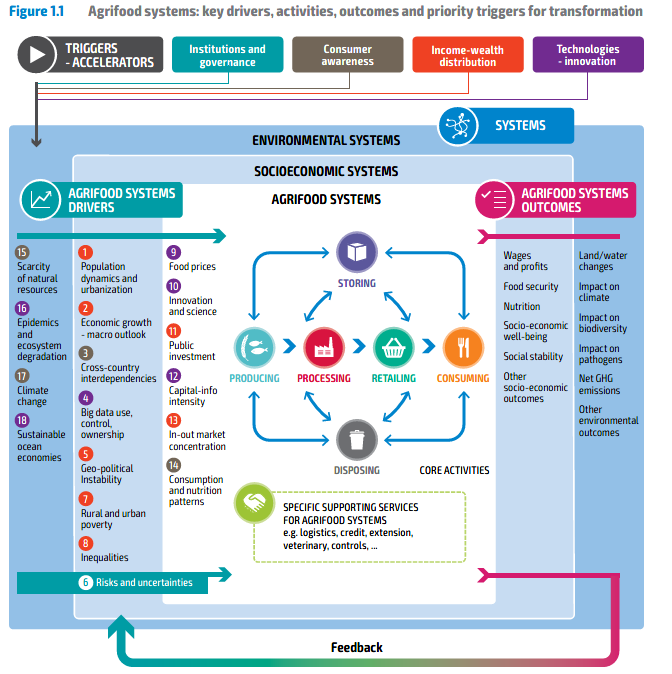

These are difficult but essential messages. The report highlights the importance of realising that food systems transformation is an inherently political and cultural process. Promising drivers and triggers for change are occurring globally, but must be harnessed and adapted. Let’s have a look at some of the drivers identified. Drivers are categorised as ‘overarching, systemic drivers’, which often include global, geopolitical and demographic elements, ‘drivers affecting food access and livelihoods’, and ‘drivers that affect food and agricultural production and distribution processes. Drivers within these categories affect agri-food, socioeconomic and environmental systems (Figure 1.1).

Captured in an agri-food system framework (partially based on previous work from Foresight4Food), some predominant drivers include scarcity of natural resources, epidemics and ecosystem degradation, cross-country interdependencies, inequalities, big data use and control, geopolitical instability, food prices, public investment and consumption and nutrition patterns. Cutting through these drivers are ‘risks and uncertainties’, as many drivers can turn into hazards, risks and cascading crises.

New Future Scenario Narratives

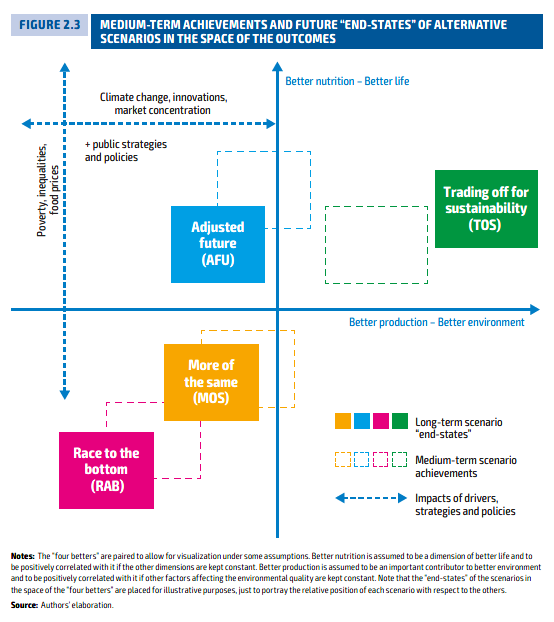

Radically divergent futures can emerge if the interactions of drivers, changes in individual and collective behaviour, the materialization of natural events, risks and uncertainties, and the influence of public strategies and policies play out differently. FAO developed four scenarios from the near future to the end of the century and explored the implications of each for food systems. The FAO ‘Four Betters’ were used to formulate four visions and narratives of the future. Using a ‘back-casting approach’ (where a number of aspirational visions are developed and it is then explored what future pathways could lead to these futures). The FAO team explored how each of these futures could be reached through combinations of key drivers, interconnections between agri-food, socioeconomic and environmental systems and ‘weak signals’ of possible futures.

By imagining alternative pathways and priority trigger points, the four scenarios are not defined as separate destinations to get to by moving along four different train tracks. Instead, each future

scenario could be reached at different points depending on the strategic policies and decisions implemented, the trade-offs in policymaking, and unless irreversible processes are triggered.

Trade-offs now and in the future will offer wicked dilemmas for decision-makers. Foresight thinking highlights that certain current decisions may lead to short term results but can increase medium and long-term uncertainty and, in the worst situations, foreclose certain long-term futures. See various conflicting policy objectives in Table 2.2.

The four scenarios are visualised on a juxtaposition of 2 paired FAO ‘Betters’: ‘Better nutrition/Better life’; and ‘Better production/Better environment’. These betters were paired to enable visualisation and relative positioning of futures vis-à-vis each other in a matrix.

The four scenarios include:

1. More of the Same (MOS)

2. Adjusted Future (AFU)

3. Race to the Bottom (RAB)

4. Trading off for Sustainability (TOS)

More of the Same involves muddling through reactions to events and crises while doing just enough to avoid systemic collapse, which will lead to the degradation of agri-food systems’ sustainability and to poor living conditions for many, increasing the long-run likelihood of systemic failures. Adjusted Future entails that some moves towards sustainable agri-food systems will be triggered in an attempt to achieve Agenda 2030 goals. Some improvements in terms of well-being will be obtained, but the lack of overall sustainability and systemic resilience will hamper their maintenance in the long run.

Race to the Bottom is characterised by gravely ill-incentivized decisions that will lead to the collapse of substantial parts of socioeconomic, environmental and agri-food systems, with costly and almost irreversible consequences for a vast number of people and ecosystems. Trading off for Sustainability would mean that awareness, education, social commitment, sense of responsibility, participation and critical thinking will trigger new power relationships and shift the development paradigm in most countries. Short-term gross domestic product (GDP) growth will be traded off for the inclusiveness, resilience and sustainability of agri-food, socioeconomic and environmental systems.

Each scenario narrative explores how certain key domains could develop. What would geopolitics, economic growth, demographics, resources and climate, agriculture, and technology and investment in food systems look like in each future? How each key driver would materialise in each future is also illustrated. For instance, the driver ‘Innovation and Science’, in the MOS scenario, imagines that various agricultural technologies such as robotics, blockchain and AI were developed and were expected to support data-driven transformation but failed in the face of too much focus on means and not enough institutional and social innovation. In the AFU scenario, some investments in novel technologies helped improve productivity and resource use efficiency.

However, more systemic approaches such as agroecology and multi-cropping were not followed through and unequal investment across countries took place, meaning that real transformation was incomplete. In the RAB scenario, science was further used to ensure control of corporate entities or geopolitical allegiance, reinforcing inequalities and further exclusion of small-scale actors and leading to faster exhaustion of natural resources. Finally, in the TOS scenario, science and innovation are fully geared toward sustainable food systems and involve strong contributions from educated and aware civil societies using innovative decision-making processes. Greater awareness of consumers facilitated the trade-off of outputs with sustainability and supported the creation of a diverse and resilient agri-food system across communities.

Various assumptions always play a role in developing scenarios and their policy triggers. Compared to previous scenario exercises, a key assumption, due to updated data models and prognoses, is that the collapse of substantial parts of agri-food, socioeconomic and environmental systems is almost certain(!). A second important assumption in the TOS and RAB scenarios is that ‘globally emerging well-educated, informed, critical, increasingly aware and non-manipulable civil societies’ are a crucial factor that either can enable or prevent those futures from being realised. Another assumption is that governance of markets is important to address inequalities. This is contrary to scenarios developed by the World Economic Forum, where the assumption was that if markets are connected and economic growth is fast, inequalities will also decrease.

So, what does it mean to work with these futures?

Concluding most directly: the picture is not reassuring, but something can be done if with urgency. SDG achievement is off track, finding ‘win-win’ solutions is difficult if not impossible, and MOS and RAB scenarios must be avoided with great urgency as they could very well become reality. However, the implications of the scenarios and the complexity of food systems also mean that other lessons require deeper reflection. Two elements are essential to underline: the interconnectedness of systems and our abilities to boost transformative change.

The interconnectedness of systems means that negative trajectories and global challenges can cascade into even bigger crises. Solutions cannot emerge easily due to entangled problems within agri-food, socioeconomic and environmental systems. Climate change, shock resilience, sustainable resource use, poverty and ending hunger are at the top of overarching challenges.

Agency grants us the means to set a new path, but it may be challenging to implement change under the influence of drivers and opposing power and interests. As such, being on the path toward MOS or RAB does not mean that we cannot set in a new direction. We must utilize ‘priority triggers of change’ or boosters of transformative processes to move away from business as usual. The report identifies four key policy triggers: institutions and governance; consumer awareness; income and wealth distribution; and innovative technologies and approaches.

Following a systemic logic, changes made through these triggers within the agri-food system should also impact socioeconomic and environmental systems. Activation or deactivation of these triggers (especially regarding which stakeholders gain the power to influence the manner of their activation) will highly influence the realisation of certain scenarios. For instance, better institution and governance mechanisms will influence on a range of key drivers and domains, such as better institution and governance mechanisms will influence on a range of key drivers and domains, such as governance of new technologies, migration, market power and intergenerational equity.

The report concludes with the words of Antonio Gramsci, Italian philosopher and radical journalist. “My mind is pessimistic, but my will is optimistic. Whatever the situation, I imagine the worst that could happen in order to summon up all my reserves and will power to overcome every obstacle”: words to be taken to heart. Acceptance of long-term perspectives by citizens and their governments is crucial for transformative action to start now. We must ‘outsmart’ political-economic constraints and enlarge agency space.

As Foresight4Food, we are committed to promoting and enhancing foresight approaches to strategically prepare for different food systems outlooks, by learning from the past but especially looking forward to explore.

COVID-19 is a deep disruption to human systems. The world is having to muddle through huge uncertainties about the consequences and longer-term impacts. This requires ‘thinking the unthinkable’ and exploring ‘neglected nexuses’. A key issue is how food system recovery pathways might unfold, especially given the “Build Back Better” mantra now being voiced by many leading decision makers.

Even before the outbreak it was clear that a profound a transform of food systems is needed for good nutrition, inclusive development and environmental sustainability. This combined with major concerns about the resilience of food systems, particularly in the face of climate change, led the UN Secretary General to call for a Food Systems Summit in 2021.

The current economic and social crisis induced by COVID-19 underscores the critical need for food systems that are resilient to shocks (particularly given underlying stresses), and which in times of crisis can protect the welfare of all, especially poor and vulnerable food producers and consumers.

Over the last months many assumptions and projections about poverty levels, nutrition, food trade, vulnerability of different groups and achievement of the SDGs have gone out the window. Scenarios of increased poverty and inequality are seeming far more likely. Updated perspectives, framing and insight are urgently needed. Leadership, decision making, and advocacy have a critical need for rapid “collective intelligence” gathering and synthesis about what is happening to food systems, emerging risks, opportunities, and the options for responding.

However, in these times of turbulence, uncertainty, novelty and ambiguity (TUNA), conventional data collection, modelling and analytical mechanisms are not enough. They need to be be complemented by greater attention for existing scenarios and analysis that highlight the risks of global disruptions, and by additional intelligence gathering to provide rapid and meaningful insights into what post COVID-19 futures might look like.

This calls for sense making and decision processes appropriate to high levels of complexity and uncertainty. Such processes need to draw on human capabilities for perceiving, communicating and recognising complex patterns, which can be connected into networks for collective intelligence and adaptive responses. There is well developed theory and methodology to support such an approach. In essence it involves:

- Creating heightened and rapid ‘situational awareness’ through sensing methods that ‘probe’ for critical changes in systems using peoples experience to judge what is important and significant, while using diverse perspectives and dissent to also detect ‘weak signals’.

- Sense making through opening up spaces for structured collective deliberation by actors with diverse backgrounds, experience, perspectives and interests, and making use of rapidly sourced coherently structured ‘narrative information’.

- Engaging stakeholders and decision makers in well informed scenario thinking about risks, opportunities and transformative pathways.

- Reconfiguring decision making and innovation through more inclusive and diverse forums that engage decision makers in processes built around principles of complexity analysis and scenario thinking.

Over the coming weeks Foresight4Food will be working with the Forum for Agricultural Research in Africa (FARA) to provide an online webinar series to help practitioners use foresight and scenario approaches to assess the potential impacts of COVID-19 on food and agriculture.

Blog by Jim Woodhill – Foresight4Food Initiative Lead