By Bhawana Gupta and Monika Zurek

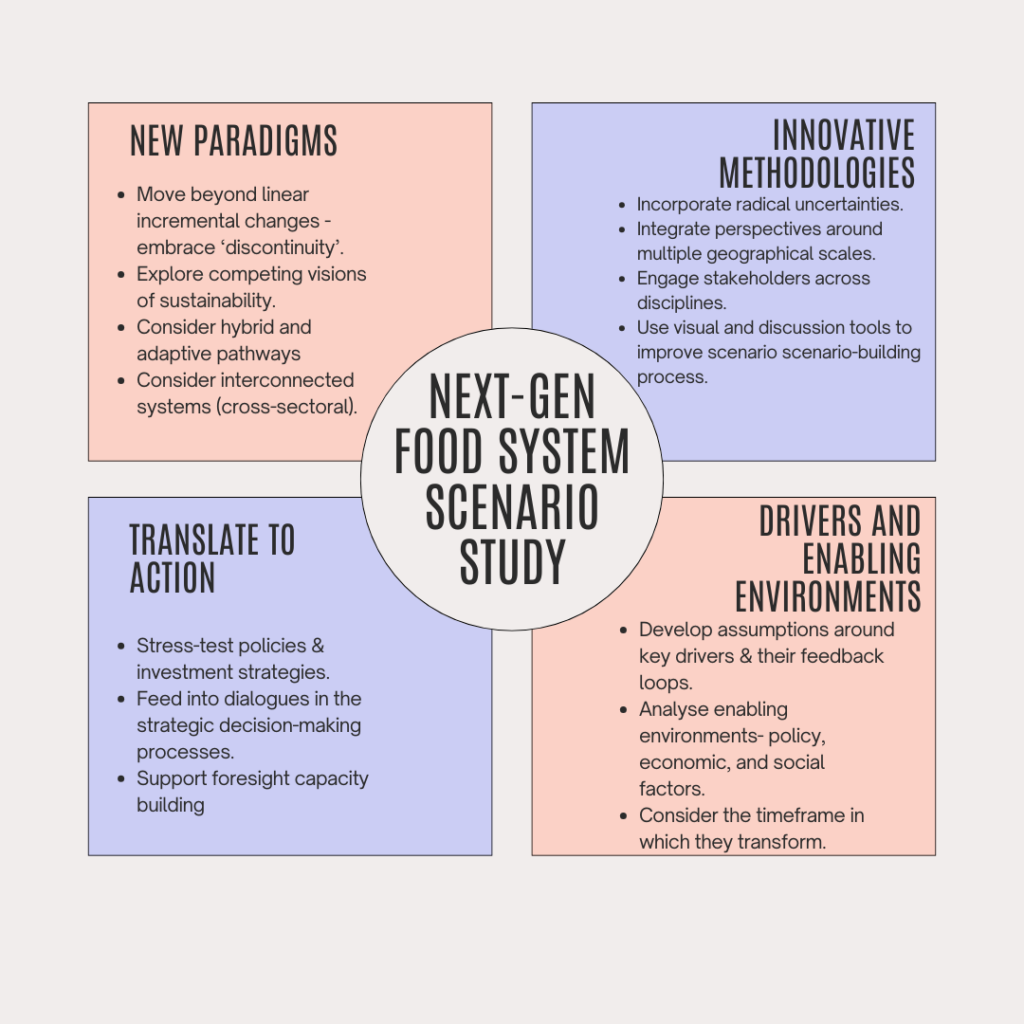

What if the future of our food system looks nothing like what we’ve imagined so far? Our recent report “Food systems of the future” examines how foresight studies are shaping our view of what’s to come. It reveals the urgent need for a new wave of forward-thinking work that dares to imagine fundamentally different food system configurations. Next-generation food system scenarios must embrace a new change paradigm, innovative methodologies, and a clear pathway to incentivise action through a deeper understanding of future drivers and enabling environments.

Why do we need another global-level scenario study?

We live in what many call the acceleration phase of the Anthropocene, an era defined by rapid and unpredictable change. For years, scholars and practitioners across disciplines worked to unravel the complexities of our global food system, using scenarios as vital tools to explore how different forces shape its future. But it’s crucial to remember that these scenarios are not only built on data; our assumptions, beliefs also shape them, and our constantly evolving grasp of the drivers of change[i].

The evolution of food system scenarios reflects this shift. Early models mostly focused on projecting food production and demand based on population growth. Over time, their scope broadened to encompass factors like resource availability, climate change, policy shifts, and socio-economic dynamics. Yet, the turbulent events of the past five years—think of the global pandemic, geopolitical tension, and unexpected supply chain disruption—have shown us that even the most sophisticated scenarios failed to capture certain uncertainties.

Grappling with the multifaceted complexities of the future is undoubtedly a wicked problem. But by continually refining our foresight techniques, we can better prepare for future shocks and proactively design alternative pathways. Let’s explore the critical building blocks for this next generation of global food system scenarios.

1. New paradigms

In Donella Meadows’ view, a paradigm is a shared set of beliefs, values, and assumptions that underlie a system. This core mindset dictates the system’s goals, structures, and operational rules. It follows that a paradigm shift is one of the most powerful drivers of lasting change within a system. For our discussion, there are three aspects that should be considered:

- Discontinuity: Past scenario studies often urged the inclusion of a surprise element or discontinuity[ii] (read box 1 for definition). However, these discontinuities were considered weak in almost all scenarios, especially quantified ones. Instead, scenario studies emphasised continuous incremental changes in the system. Going forward, our scenarios must move beyond a smooth and predictable evolution to explicitly explore non-linear changes, tipping points, and abrupt shifts.

BOX- 1

The term discontinuity is used variously in scenario literature, broadly signifying a sharp departure from past trends caused by high-impact developments, phenomena, and events. The significance of a discontinuity depends on its character, magnitude, speed, and ripple effects, and whether it has been anticipated and ameliorated. Here, a discontinuity refers to a significant shift of social-ecological structure and dynamics, rather than a transient perturbation after which the system reverts to its original trajectory. Related terms are surprises, bifurcation, critical transition, tipping points, tipping elements, wild cards, and black swan events. More recently, the phrase game changers has been introduced for shifts in how society is organized through understandings, values, institutions, and social relationships.

- Mental models: Since the IPCC’s ‘Shared Socio-economic Pathways’, most global scenario studies have relied on a mental model that assumes four broad pathways:

- A sustainable pathway characterised by progressive policy and technological adoption.

- A business-as-usual pathway, projecting a continuation of current trends.

- A collapse or environmental destruction pathway, depicting worst-case outcomes.

- A divided world pathway, where inequalities worsen and cause socioeconomic distress.

While seemingly intuitive the widespread use of this mental model is influenced by cultural biases, cognitive processes[iii], and the culture of scientific reticence[iv] (read box 2 for more). These factors can lead to the design of scenarios that are overly simple, feel intuitively right, and align with common ways of thinking about the future: an optimistic view, a middle ground, and a pessimistic view. We must challenge this reliance on simplistic archetypes and embrace more nuanced and multi-dimensional perspectives in our scenario development.

BOX- 2

Anchoring bias: We tend to rely too heavily on initial information, making it difficult to envision radically different futures.

Confirmation bias: We seek out information that confirms our existing beliefs, reinforcing the status quo.

Incrementalism: We assume change will be gradual and predictable, neglecting the potential for sudden, non-linear shifts.

Lack of interdisciplinary input: Many scenario studies are limited by the perspectives of a narrow range of experts, missing crucial insights from other fields like sociology, ecology, and complexity science.

- Cross-sectoral linkages: Too often, scenario studies operate in isolation, focussing on a single system like food. They fail to incorporate the strong interdependencies with other critical systems such as energy, water, or social systems. This approach can create a lack of understanding of the potential for cascading system failures, or conversely, unexpected positive feedback loops. Future scenarios must explicitly model these intricate interconnections, exploring how changes in one sector can trigger ripple effects across others.

2. Innovative methodologies

Advancing food system scenarios requires leveraging innovative methodologies, for example:

- Multi-scale analysis: Most past food system scenario studies focused on processes at specific geographic scales. Yet food systems operate across a spectrum, from individual households to global markets, with numerous complex inter-dependencies. These dynamics need to be captured in the future studies. The methodology for linking scenarios at different scales was explored by Zurek et al[v]. By integrating local, regional, and global food system dynamics, we gain a more holistic understanding of potential futures.

- Radical scenario development: The scenarios developed in the last decade have often underplayed outlying, surprise, or disaster events[vi]. Yet the inclusion of diverse and radical uncertainties can advance the quality and utility of scenarios[vii]. The development of radical scenarios combines established scenarios with group discussion techniques, as discussed in Talwar et al.[viii]. We need to better embrace wild cards and black swans as integral parts of scenario development, exploring how low-probability, high-impact events can reshape the future.

- Multi-disciplinary expert involvement: Food systems are inherently complex and interconnected, necessitating the involvement of actors across multiple sectors (e.g., agriculture, trade, health, and environment) and governance levels (from local to global). Innovative participatory methodologies such as Transdisciplinary Foresight Labs[ix] and Causal Layered Analysis (CLA)[x] can unpack issues on various levels and uncover underlying assumptions around litany, systemic causes, worldviews, and myths that shape expert opinions. Together, these methodologies support more holistic, inclusive, and imaginative scenario processes.

3. Drivers and enabling environments

Today’s scenarios commonly describe assumptions around the drivers of change (e.g. technological shifts, demand patterns, and trade dynamics). Next-generation studies must go further and reflect on the enabling environments that shape the dynamics of future food system drivers and the timeframe within which the change unfolds. This includes[xi]:

- Policy and governance: How do regulations, institutional capacity, and international agreements shape food system operations?

- Economic and financial structures: How do investment patterns, trade dynamics, and economic inequality influence food access and production?

- Social and cultural context: How do changing consumer preferences, social equity, and cultural norms drive food demand and system practices?

- Technological and infrastructural frameworks: How does digital connectivity, research and development (R&D), and infrastructure development enable or constrain food system innovation?

- Environmental governance: How do policies and practices regarding resource management and climate change impact food production sustainability?

4. Translate to action

Developing next-generation scenarios is not just an academic exercise. To be truly impactful, these studies must bridge the gap between foresight and implementation, ensuring that scenario narratives translate into policy and strategic actions. This involves:

- Using real-world stress tests: Running policies and investment strategies against multiple scenario conditions to assess their resilience.

- Embedding scenario thinking: Integrating foresight and scenario planning directly into decision-making processes at national and global levels. (Read about institutionalising foresight in decision-making in another blog).

- Engaging non-traditional stakeholders: Involving a broader range of voices, including grassroots organizations, indigenous groups, and regenerative farmers, to develop a shared language around food systems and future pathways.

Conclusion

Essentially, the prevailing paradigm in many current scenario studies inadvertently restricts our imagination and limits our collective ability to envision and prepare for truly transformative change. It creates an illusion of control in a world that is far more contingent and unpredictable. The necessary shift towards scenario studies that adequately reflect paradigm shifts is a complex but crucial endeavour, requiring a fundamental rethinking of how we construct and interpret future possibilities.

The food system of tomorrow will not be shaped by predictions, but by our collective capacity to anticipate, adapt, and transform. Advancing next-generation global food system scenarios requires bold thinking, cross-sector collaboration, and an openness to radical possibilities. The question remains: are we ready to embrace this challenge?

[i] Cork, S., Alexandra, C., Alvarez-Romero, J.G., Bennett, E.M., Berbés-Blázquez, M., Bohensky, E., Bok, B., Costanza, R., Hashimoto, S., Hill, R. and Inayatullah, S., 2023. Exploring alternative futures in the Anthropocene. Annual Review of Environment and Resources, 48(1), pp.25-54.

[ii] Rothman, D.S., Raskin, P., Kok, K., Robinson, J., Jäger, J., Hughes, B. and Sutton, P.C., 2023. Global Discontinuity: Time for a Paradigm Shift in Global Scenario Analysis. Sustainability, 15(17), p.12950.

[iii] Cork, S., Alexandra, C., Alvarez-Romero, J.G., Bennett, E.M., Berbés-Blázquez, M., Bohensky, E., Bok, B., Costanza, R., Hashimoto, S., Hill, R. and Inayatullah, S., 2023. Exploring alternative futures in the Anthropocene. Annual Review of Environment and Resources, 48(1), pp.25-54.

[iv] Rothman, D.S., Raskin, P., Kok, K., Robinson, J., Jäger, J., Hughes, B. and Sutton, P.C., 2023. Global Discontinuity: Time for a Paradigm Shift in Global Scenario Analysis. Sustainability, 15(17), p.12950.

[v] Zurek, M.B. and Henrichs, T., 2007. Linking scenarios across geographical scales in international environmental assessments. Technological forecasting and social change, 74(8), pp.1282-1295.

[vi] Gupta, B., Zurek, M.B., Woodhill, J. and Ingram, J. 2025 submitted for publication to Frontiers in Sustainable food systems

[vii] Gordon, D., 2021. Radical Uncertainty: Decision-Making Beyond the Numbers. Quarterly Journal of Austrian Economics, 24(1), pp.206-210.

[viii] https://jfsdigital.org/2019/06/15/the-future-of-energy-reinvented-case-study-of-the-radical-scenario-development-approach/

[ix] Pólvora, A. and Nascimento, S., 2021. Foresight and design fictions meet at a policy lab: An experimentation approach in public sector innovation. Futures, 128, p.102709.

[x] UNDP (2022). UNDP RBAP: Foresight Playbook. New York, New York.

[xi] Gupta, B., Zurek, M., Woodhill, J., Ingram, J. (January, 2025). Food Systems of the Future: A synthesis of food system drivers and recent scenario studies. Foresight4Food. Oxford, United Kingdom.

Reflections on the Third Global Foresight4Food Workshop in Montpellier 2023

By Bram Peters, Food Systems Programme Facilitator

Strike? What strike?

Amid the turbulence created by strikes in France, a diverse and committed group of people still managed to get to and from the Third Global Foresight4Food Workshop in Montpellier from 7-9 March.

Perhaps, as foresight practitioners, we should have seen it coming! You would think that foresight practitioners who make it their business to look into the future might be better at anticipating turbulence, or at least a substantial level of social upheaval.

Why go through the trouble to come anyway? Because food systems are in turbulence as well. Never has there been a more urgent need to transform food systems. More than 3.1 billion people globally do not have access to healthy diets. The impact of climate change in the form of droughts and disasters is increasing. Agri-food systems are responsible for one-third of greenhouse gas emissions. The Covid-19 pandemic and the Russia war in Ukraine have shown how integrated, yet fragile, the global food system is.

We need foresight in food systems transformation

Yet, “the greatest danger in times of turbulence is not the turbulence; it is to act with yesterday’s logic” (according to futurist Peter Drucker). That’s where foresight comes in.

We need a long-term perspective to explore alternative pathways to reach desirable or avoid undesirable food system changes.

Following from the UN Food Systems Summit in 2021, many countries are searching for ways to navigate change and develop anticipatory policy to guide them.

As such, the issue on the table was: how can the foresight community of practice offer support and relevant advice to food system stakeholders?

Creating a safe space to think, connect and engage

In Montpellier, Foresight4Food brought together a diverse group of foresight practitioners, researchers, users of foresight and implementors of food systems approaches to discuss how foresight can contribute to national level food systems transformation pathways amid all this turbulence.

The Masterclass on the 7th generated a lot of energy, a shared language, and many practical explorations of tools and methods. The main Workshop on the 8th and 9th saw interactive exchanges, presentations of valuable projects and sharing of insights.

Among others, organisations such as FAO, CGIAR, GFAR and CIRAD shared ground-breaking applications of foresight thinking linked to food systems. There were cases from Asia, Africa; thematic cases on food systems data; new and past initiatives; dashboards and multi-stakeholder processes.

Researchers and data experts, such as from Wageningen University and Food and Land Use Coalition, shared innovative tools and models to advance new ways of projecting trends.

Critical perspectives were shared. Insights were brought from Africa and Asia, such as by Forum for Agricultural Research in Africa, and much more.

Moving the needle: developing our forward agenda

We, as Foresight4Food team, gained a lot of energy and motivation to continue fostering this vibrant network.

A few pickings of things we want explore moving forward. Develop and encourage ‘Communities of Practices’ through active partnership principles. Make a meta-analysis of existing food system foresight cases and comparative insights and lessons. Create guidance for foresight community on the process of actually doing foresight for food systems. Develop key principles for quality approaches and a toolbox to support implementation.

Thankfully, even in the face of the French strikes, a quality characteristic among foresight practitioners is the ability to be adaptable and flexible – as is needed when you work with the complexity of food systems.