By Bram Peters

The future of food systems is uncertain, yet one thing is clear—transformative change is urgently needed. Climate change, inequality, and geopolitical instability are reshaping how food is produced, distributed, and consumed. How can we navigate these complexities and create a more sustainable, resilient food system?

At the Power of Foresight Workshop held on 30-31 January 2025 at the FAO headquarters in Rome, experts and practitioners gathered to discuss how foresight can drive food systems transformation. Their insights reveal a crucial truth: the process itself— working with complexity, embracing inclusivity, diverse perspectives, and collective intelligence—is central to making real progress.

Insights from the ‘Power of Foresight’ Workshop

- 17 different cases and the stories of 48 participants from 27 countries demonstrated that foresight approaches have much to offer to the process of food systems transformation

- Working with complex systems is what it’s about, and effective foresight practices for food systems change to embrace this

- Openness to new and inclusive perspectives should be central to all foresight for food systems transformation efforts

- The process brings the answer – and foresight can bring awareness of crucial process elements such as collective intelligence, agency, time and scale

- Embracing the ‘ifs’: how you do foresight, and what comes before and after, is just as important as the development of scenarios

- Foresight is not one approach or one methodology – there are a diversity of ways to go about it

- The national food systems pathways can benefit from foresight approaches

Photos: 30 January 2025, Foresight4Food workshop. FAO Headquarters, Rome. Photo credit: ©️FAO/Cristiano Minichiello

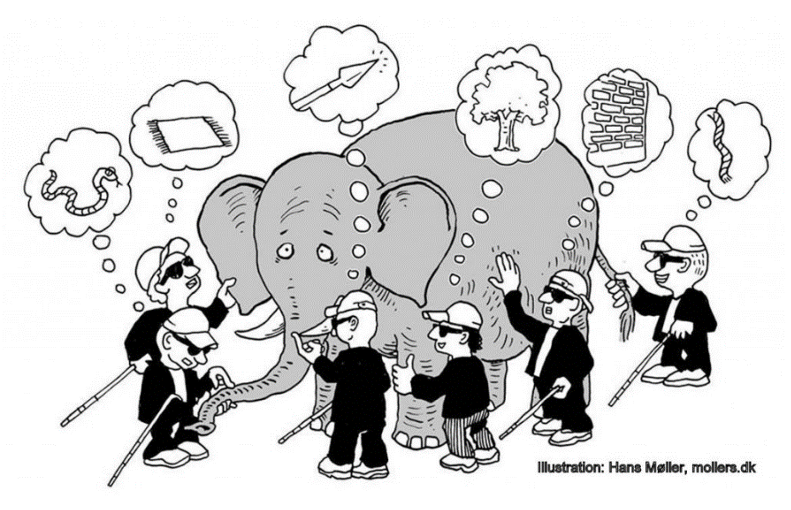

Working with complex systems: Let’s talk about the elephants in the room

When it comes to food systems transformation, there isn’t just one elephant in the room—there are many. These metaphorical elephants represent the complex, interconnected challenges we face, and ignoring them only hinders progress.

- First, as a whole range of interrelated challenges and assumptions we are not working on enough: whether that’s climate change, human rights, global geopolitical turbulence, growing inequality. All these challenges together form a context of global polycrisis.

- Second, we can see elephants in the room related to our apparent inability to take decisive transformative action in food systems: a lot of talk, limited action.

- Finally, we can see elephants as representing systems. An elephant can represent a dynamic, complex food system, of which we might only be able to see or understand the trunk, tusks, ears or tail.

Like the elephant and the blind men metaphor (see image to the right), food systems are deeply interconnected with global issues like climate change, inequality, and geopolitical instability. Tackling these requires a holistic approach, recognizing that transformation cannot happen in silos.

Gather new and inclusive perspectives – and change your own

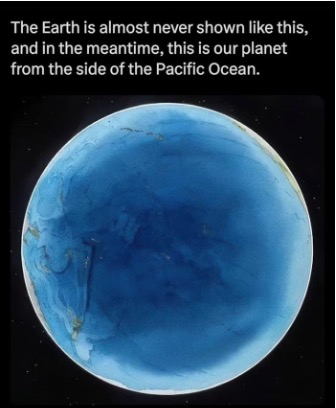

What’s central to talking about complex food systems is perspective. We all have different mental images of food systems—whether local agriculture, marine ecosystems, or trade networks. Expanding our perspectives helps identify new entry points for addressing issues like malnutrition, poverty, and sustainability.

For some, like from the Pacific region, it’s about marine ecosystems in which food is central. Changing your perspective can be a helpful way of looking at a complex topic: such as to see the Pacific food system composed not of ‘small island states’ but rather ‘large ocean states’ connected with the global food system through trade, governance, and oceanic currents. Why is flipping your perspective so important? It helps to reframe entry points for discussion with other stakeholders and view the root causes of things like malnutrition, non-communicable diseases, poverty and human rights abuse in food systems differently.

If you are able to change your perspective, it helps to understand the viewpoints of those less heard. Having an inclusive process to gather different viewpoints is crucial to changing perspectives and behaviour, mobilising for collective action and creating shared visions of the future.

The process is the answer

Ever tried herding cats? Well, transforming food systems is about fostering C.A.T.S.—a process centred on:

- Collective intelligence – Multi-stakeholder collaboration and co-creation

- Agency – Empowering change through action

- Time – Bridging past, present, and future

- Scale – Recognizing interconnections between local and global systems

So, what does it mean to herd cats when talking about food systems? It means there are no magic bullets: the process is central to the outcome.

Effort on addressing the ‘ifs’

Foresight can be of great added value to support the food systems transformation process. Whether it is about co-creating alternative futures, conducting backcasting towards a more desirable scenario, highlighting the cost of delayed action, or informing anticipatory policy – foresight and scenario tools are a key toolbox in the hands of systems change champions.

In order for foresight to be effective, there are a number of conditional ‘ifs’ i.e., if foresight experts and facilitators:

- Are able to move beyond added value, tackling pre-conditions, obstacles, and constraints affecting how stakeholders prepare for the future.

- Not only preach to the converted – we need to involve stakeholders who think and act differently

- Are cognizant of power differences, lock-ins and political economy

- Build on other approaches that also provide value, such as design thinking, human-centred development and mission-oriented policy making.

- Pay attention to what comes before and after the development of scenarios

Scenarios only developed from the perspective of single organisations or without meaningful consultation and dialogue will not be effective.

Foresight approaches and national food systems pathways

There are a broad range of foresight approaches, some expert-driven or participatory, others quantitative, experiential, creative or analytical. Each has their value – but these needs come from a clear user need and scope within a food system. However, it is essential to keep in mind that foresight is a tool, not a panacea, and cannot address all questions.

With 156 national convenors driving progress through implementing 137 national food systems transformation pathways, the upcoming UNFSS+4 Stocktaking Moment (July, Addis Ababa) presents an opportunity to share lessons and strengthen impact. What we have seen the past two days in Rome, is the incredible richness and diversity of initiatives that use foresight to support the food systems transformation process.

Sharing the lessons from these initiatives, communicating the potential of foresight, and supporting the national convenors to further realise the impact on transforming food systems outcomes will be crucial in the run-up to the Stocktaking Moment.

Reflections on the Third Global Foresight4Food Workshop in Montpellier 2023

By Bram Peters, Food Systems Programme Facilitator

Strike? What strike?

Amid the turbulence created by strikes in France, a diverse and committed group of people still managed to get to and from the Third Global Foresight4Food Workshop in Montpellier from 7-9 March.

Perhaps, as foresight practitioners, we should have seen it coming! You would think that foresight practitioners who make it their business to look into the future might be better at anticipating turbulence, or at least a substantial level of social upheaval.

Why go through the trouble to come anyway? Because food systems are in turbulence as well. Never has there been a more urgent need to transform food systems. More than 3.1 billion people globally do not have access to healthy diets. The impact of climate change in the form of droughts and disasters is increasing. Agri-food systems are responsible for one-third of greenhouse gas emissions. The Covid-19 pandemic and the Russia war in Ukraine have shown how integrated, yet fragile, the global food system is.

We need foresight in food systems transformation

Yet, “the greatest danger in times of turbulence is not the turbulence; it is to act with yesterday’s logic” (according to futurist Peter Drucker). That’s where foresight comes in.

We need a long-term perspective to explore alternative pathways to reach desirable or avoid undesirable food system changes.

Following from the UN Food Systems Summit in 2021, many countries are searching for ways to navigate change and develop anticipatory policy to guide them.

As such, the issue on the table was: how can the foresight community of practice offer support and relevant advice to food system stakeholders?

Creating a safe space to think, connect and engage

In Montpellier, Foresight4Food brought together a diverse group of foresight practitioners, researchers, users of foresight and implementors of food systems approaches to discuss how foresight can contribute to national level food systems transformation pathways amid all this turbulence.

The Masterclass on the 7th generated a lot of energy, a shared language, and many practical explorations of tools and methods. The main Workshop on the 8th and 9th saw interactive exchanges, presentations of valuable projects and sharing of insights.

Among others, organisations such as FAO, CGIAR, GFAR and CIRAD shared ground-breaking applications of foresight thinking linked to food systems. There were cases from Asia, Africa; thematic cases on food systems data; new and past initiatives; dashboards and multi-stakeholder processes.

Researchers and data experts, such as from Wageningen University and Food and Land Use Coalition, shared innovative tools and models to advance new ways of projecting trends.

Critical perspectives were shared. Insights were brought from Africa and Asia, such as by Forum for Agricultural Research in Africa, and much more.

Moving the needle: developing our forward agenda

We, as Foresight4Food team, gained a lot of energy and motivation to continue fostering this vibrant network.

A few pickings of things we want explore moving forward. Develop and encourage ‘Communities of Practices’ through active partnership principles. Make a meta-analysis of existing food system foresight cases and comparative insights and lessons. Create guidance for foresight community on the process of actually doing foresight for food systems. Develop key principles for quality approaches and a toolbox to support implementation.

Thankfully, even in the face of the French strikes, a quality characteristic among foresight practitioners is the ability to be adaptable and flexible – as is needed when you work with the complexity of food systems.

By Jim Woodhill, Lead Foresight4Food Initiative

How can we understand the multiple dimensions of transforming food systems? On top of the disruptions to peoples’ incomes and food supply chains caused by COVID, the Russia war in Ukraine has pushed fertilizer, energy and food prices to all-time highs. Millions are falling back into hunger and poverty. Even in the affluent world, many poorer people in society are being forced to use food banks, eat lower nutritional value food, and make tough decisions between using their dwindling financial resources to pay for food or keep their houses warm in winter.

This situation underscores the conclusions of the UN Secretary General’s 2021 Food Systems Summit that highlighted the need for a far more resilient, equitable and sustainable food system. Heads of state universally declared that a transformation of food systems is needed to cope with climate change, tackle hunger and poor nutrition, reduce poverty, and protect the environment.

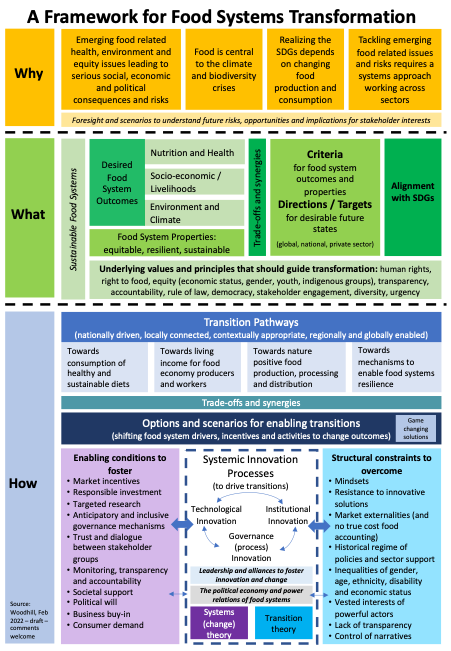

But what does food system transformation actually mean? In this blog, I outline a framework (Figure 1 below) for thinking about food systems transformation. It is based on WHY change is needed, WHAT needs to change, and HOW change can be brought about.

Introducing food systems transformation

“Food systems” has provided a new framing for a more integrated approach to the issues of food security and nutrition, agriculture, climate change, environment and rural poverty. This systems view makes a lot of sense as, one way or another, how we consume and produce food is central to all the Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs). Billions of people work in the agri-food sectors, everyone needs a healthy diet, food is central to culture, food trading and retailing are huge markets and agriculture is the biggest user of land and water resources.

This systems perspective is bringing together a plethora of associated ideas, language and concepts. Terms such as food system outcomes, transformation, transition pathways, resilience, equity, trade-offs and synergies, living income, nature positive approaches, agroecology and the true-cost of food are just a few of these. The emerging food systems discourse is also giving more attention to power structures, the political economy, stakeholder engagement and dialogue, empowering excluded voices, market externalities, coalitions, economic incentives, and data needs.

Before explaining the framework, let’s ask what is meant by a transformation of food systems. Transformation means a complete or radical change of something in form, function or appearance. So, transforming food systems means fundamentally changing how they operate to dramatically improve environmental, health and livelihood outcomes for society at large. This requires fundamental changes in the behaviour of consumers, investors, agri-food sector firms, farmers, researchers and political leaders. In turn, a dramatic shift in economic and social incentive structures is needed, with the true cost of food embedded into how markets function. To avoid future risks these fundamental changes are needed with urgency.

To-date, and perhaps not surprisingly, much of the debate and political narrative has focused on what needs to change and why. The more difficult question of how change can actually be brought about has so far received less attention. Perhaps this is because such discussion cannot avoid difficult political-economic issues of long-term collective interests versus short-term vested interests. We are still a long way from having sufficiently detailed strategies, plans of action, policy commitments and investments to bring about the transformation. How to get from WHY to HOW?

WHY transform food systems?

Why food systems need to change has been well analysed, is clear to most stakeholder groups, and is increasingly articulated by political leaders. The problems and longer-term impacts and risks of the way food is currently consumed and produced is well-evidenced in terms of the negative consequences for health, the environment, and equitable economic development. If this interconnected set of issues is not tackled effectively and promptly the risks of dire longer-term social, economic and political consequences are high.

Food value chains contribute about a third of total greenhouse gas emissions. Agriculture and fishing are by far the largest causes of biodiversity loss and ecosystem degradation. These impacts on the environment cycle back to undermine the Earth’s very capacity to produce food for the long run.

Further, it is increasingly clear that the SDGs and in particular SDG1 – no poverty – and SDG2 – zero hunger – will not be achieved without a fundamental change in how food systems function.

The work of the Food Systems Summit brought a much wider understanding and acceptance that the numerous development issues linked to food can only be effectively dealt with through a cross-sectoral and systems-oriented approach. An additional critical aspect of the food systems framing is an acceptance that these issues are of equal importance for countries in the Global North and the Global South.

Foresight and scenario analysis can make a vital contribution in helping to explore the ways food systems might change and with what risks and opportunities for different stakeholder interests.

WHAT needs to be transformed?

The desired outcomes from food systems have become well-articulated in terms of three main areas:

- ensuring food security and optimal nutrition for all.

- meeting socio-economic goals, in particular reducing poverty and inequalities.

- enabling humanity’s food needs to be met within planetary environmental and climate boundaries.

Overall, food systems are recognized as needing to function with the properties of being resilient to shocks, sustainable over the long-term and equitable in terms of the costs and benefits to different groups in society.

Across these food system outcomes and properties, there are inevitable trade-offs and synergies, which bring with them the potential for both conflict and collaboration between different interest groups. While the broad directions for desired food system outcomes and properties are relatively well established, the nature and extent of these synergies and trade-offs is much less well understood. More work is also needed to establish specific criteria, directions for change and targets for food system outcomes, which will be necessary to guide transformation at national or local levels, within sectors or across business operations. More attention needs to be given to how the criteria and targets for food systems transformation align with those of the SDGs.

The Food Systems Summit and the work of the Committee on World Food Security (CFS), in particular its recently adopted Voluntary Guidelines of Food Systems and Nutrition (VGFSyN), have identified underlying values and principles that should guide the processes and outcomes of food systems transformation. These include human rights (incl. the right to adequate food), sustainability, resilience, transparency, accountability, adherence to the rule of law, stakeholder engagement, gender equality, and inclusivity (particularly for women, youth, indigenous groups and small-scale producers).

Food systems that deliver on the desired outcomes and properties, and function in adherence with the underlying values and principles articulated above, can be considered as sustainable food systems.

HOW can food systems be transformed?

The transformation of food systems will require a focus on transition pathways, largely driven at the national level but connected with local processes and enabled by larger-scale system shifts at regional and global scales. Four main transitions can be identified from the Food Systems Summit deliberations:

- a consumption shift to sustainable and healthy diets.

- an equitable economic shift to ensure food economy producers and workers, have a fair living income including being able to afford healthy diets.

- a shift toward nature positive approaches for food production, processing and distribution which have a net-zero climate impact and operate within a sustainable and safe zone of utilizing natural resources.

- a shift towards mechanisms of resilience for food systems which can ensure societies a large to not risk food insecurity and that groups who are poor or vulnerable are protected.

Desired food system outcomes can potentially be achieved through multiple different pathways and scenarios with numerous different trade-offs and synergies. For example, consumption shifts could be influenced by food prices and taxes, public education, product labelling or shifts in food marketing practices. Resource efficiency and circularity could be achieved by a number of measures, including consuming (at a global level) less animal protein, adopting agroecological approaches, energy efficiency, water management, reducing waste, or new technologies which reduce methane emissions from cattle farming. Equity for those working in the sector could be improved through various combinations of increasing food prices, implementation of labour and land tenure rights, improved social protection, improving overall rural economic development or creating greater economic opportunity outside the food sector.

Developing and assessing the options and scenarios to enable transitions is where a vast amount of investment and work is needed if food systems are to be sustainably transformed. The Food Systems Summit process identified a significant number of “game changing solutions”, ideas that could contribute to developing viable transition pathways. Further assessment and work will be needed to refine, prioritize and build on this contribution from the Summit.

Scenarios can help identify potential trade-offs and co-benefits of those solutions across intended food system outcomes. The principles of equity and inclusion are especially important to consider when analysing options and trade-offs. For example, gender equality is not guaranteed to improve with increased income from food systems activities, so attention must be paid to gender-transformative and inclusive value chain development.

Generating viable options for transforming food systems will require systemic innovation that connects processes of innovation across the domains of technology, institutions and social norms, and politics and governance. Food systems transformation will be impeded or enhanced depending on the constellation of power relations across societies and the agri-food sector. This is particularly salient where influential actors are prepared to defend vested interests at the cost of changes for the wider collective good. Such systemic innovation will require profound paradigm shifts and completely new approaches to policy coherence.

Insights from systems theory and transition theory have much to offer in terms of how to guide and broker change in complex (food) systems. For example, encouraging, supporting, linking and scaling up “niche” innovations that can respond to new needs, challenges and opportunities. This requires adaptation to local contexts that can be supported by territorial approaches to development. Over time, such innovations can help to disrupt existing and unsustainable food systems “regimes” (attitudes, policies, power relations, market relations) and enable more sustainable alternatives to become embedded.

The Food System Summit has helped to identify numerous factors that can be considered as enabling conditions or structural constraints for food systems transformation. Systems change involves “nudging” systems in desirable directions by working to amplify enabling conditions and dampening structural constraints. This requires attention to the underlying political economy. Strategic alliances and political leadership are needed to help shift understanding, narratives and power dynamics.