By Bram Peters, Food Systems Programme Facilitator

The future is a mystery, full of uncertainties, risks and opportunities. Yet, humans and human systems have a remarkable ability to turn imagination into reality. In this landscape of uncertainty, foresight becomes an essential tool, helping us navigate what lies in the future. This is especially important when it comes to food systems transformation.

In this blog, I will endeavour to give you a glimpse at how foresight, awareness of the political nature of futures, and alternative scenarios can help us rethink and reshape our food systems for a more just and sustainable future.

Four Ways to Think About the Future

According to Muiderman et al. (2020), there are four main approaches to foresight:

- Assessing Probable (and Improbable) Futures

Example: The IPCC climate scenarios, which predict likely outcomes based on different climatic and environmental trends, and possible climate actions. - Contending with Multiple Plausible Futures

Example: Scenario matrices that explore what could happen in different situations under various combinations of uncertainties. - Imagining Diverse, Pluralistic Futures

Example: Visioning exercises where we picture a desired future, then work backwards (backcasting) to figure out how to get there. - Scrutinizing the Performative Power of Future Imaginaries

This approach examines how our collective visions of the future can actually shape reality.

Most foresight work focuses on the first three approaches. But in today’s world, shaped by pandemics, global conflicts, and rising political tensions, having the skills to apply the fourth approach can be considered to be more important than ever. A recent Synthesis Review of food system futures conducted by Foresight4Food identified that we can generally see various clusters of key food systems futures around ‘business as usual’, ‘global sustainability’,

‘local solutions’, ‘rising inequalities’, and ‘uncontrolled chaos’. However, it was also observed that none of these described scenarios portray very radically different food system futures.

The Power of Collective Imagination

Jasanoff and Kim, in their book Dreamscapes of Modernity (2015), introduce the idea of socio-technical imaginaries:

“Collectively imagined forms of social life and social order reflected in the design and fulfilment of nation-specific scientific and/or technological projects.”

In simpler terms, societies tell themselves stories about who they are, where they’ve been, and where they’re going. These stories—these imaginaries— can reshape history, redefine the present, and chart a course for the future. And often, they serve the interests of those in power.

The Future Is Political—and It’s Already Here

Why does this matter? Because the future isn’t just something that happens to us. It’s something that societies seek to actively shape, often through powerful narratives. Consider some current, concerning, imaginaries being promoted by powerful elites:

- Trump’s “Golden Dome” and the slogan “Make America Great Again”

- Elon Musk and other tech company elites’ visions of Artificial General Intelligence

Alternative imaginaries to counter power and transform societies toward a very different future also exist. Think about:

- The Degrowth Manifesto, as proposed by Kohei Saito in his book ‘Slow Down’

- Ministry of the Future, as narrated by Kim Stanley Robinson

Shaping Better Futures—Together

Foresight, when used critically, inclusively and deliberatively, has the power to shape more inclusive and constructive imaginaries. Jasanoff writes that these imaginaries “offers a glimpse into the realities of the known, the made, the remembered, and the desired worlds in which we live—and which we have the power to refashion through our creative, collective imaginings.”

In other words, we can—and should— together imagine alternative, inclusive, sustainable and transformative futures, making them tangible. The time to do this, at scale, is now. The Foresight4Food Global Workshop, taking place in Jordan from 15-19 June, will include an exercise on ‘Radical Food System Futures’. This will harness the collective intelligence of the foresight and food systems community, and enhance focus on imagining very different food systems than we see around us today.

Preparations are well underway for the 5th Global Foresight4Food Workshop set to take place in Amman, Jordan, from 15 to 19 June 2025. This dynamic event will bring together foresight thought leaders, innovators, and changemakers from around the world. Designed to spark dialogue, ignite creativity, and drive tangible progress, the workshop offers a unique platform to advance the global foresight agenda for food systems.

In the lead-up to the event, Asem Nabulsi —Foresight4Food FoSTr Programme Deputy Facilitator in Jordan—shares his perspectives on the critical challenges and emerging opportunities shaping global food systems. In this blog, he offers valuable insights into the urgent need for systemic change and highlights the powerful role foresight can play in building a more equitable, nutritious, and sustainable future.

Beyond the Macro Lens: Reclaiming the Food System Narrative

A critical concern shared by many in the global food space is that the decisions influencing food systems are often made at the macro level, detached from the lived realities of communities and the interconnected outcomes they produce. The fragmented approach overlooks how policies and practices affect health, nutrition, livelihoods, and the environment. Foresight provides the structure to consider these dimensions together, helping stakeholders envision multiple futures and make informed, holistic decisions.

Sharing Real-world Experiences

The success of the upcoming Foresight4Food Global Workshop hinges on more than dialogue—it depends on active participation, sharing real-world experiences, and co-creating concrete, implementable recommendations.

When foresight thought leaders, innovators, and food system stakeholders from around the world sit together, it should not just be about knowledge exchange; it should be about laying the groundwork for lasting change through mutual understanding and collective action.

From Dialogue to Action: Integrating Insights into Practice

I see this global workshop as a springboard to rethink professional strategies. One needs to fully understand the importance of multistakeholder perspectives and collaborative design of actions that consider the full spectrum of affected groups. This approach ensures that decisions are not only visionary but grounded in equity and practicality.

Regional Collaboration: The Untapped Potential

While food systems are often discussed within national borders, I would like to remind you that no country exists in a vacuum. Regional interdependence, from raw materials to trade and market access, necessitates greater collaboration. To build more resilient food systems, I suggest enhancing bilateral and multilateral trade, establishing regional food hubs, diversifying trade routes, and creating supportive regulatory frameworks. These steps could buffer regions against future disruptions and strengthen food sovereignty.

The Leadership Imperative

Leadership is essential for steering transformation. Setting a suitable regulatory environment, mapping the current food system and agreeing on the goals and best way forward to reach the desired goals, fostering a cooperative environment for change, uniting stakeholders understanding and action towards the desired goals, taking the decisions and actions that incentivise actions that enhance positive food system transformation at the different levels and for different stakeholders, raising awareness for all actors affecting and being affected by food systems, creating a national re-iterative process to regularly examine the efficacy of changes made and looking out for changing factors that might affect the food system, and starting the communication and actual practical steps for regional cooperation.

From Vision to Implementation: Making Collaboration Stick

A practical roadmap to ensure the workshop leads to a lasting impact is to focus on the importance of moving from vision to implementation. It means building a shared understanding, defining common goals, and designing actions that are informed by the perspectives of diverse stakeholders across multiple levels. Open discussions around potential trade-offs and strategies to mitigate negative impacts are also key. To translate dialogue into action, I would highlight the need for clear, well-defined plans with assigned responsibilities and timelines. I believe that this structured yet adaptable approach is crucial for fostering durable cross-sector collaboration and meaningful progress.

With these reflections in mind, I look forward to welcoming you in Jordan and seizing this unique opportunity to catalyse both regional and global efforts toward meaningful food system transformation.

By Bhawana Gupta and Monika Zurek

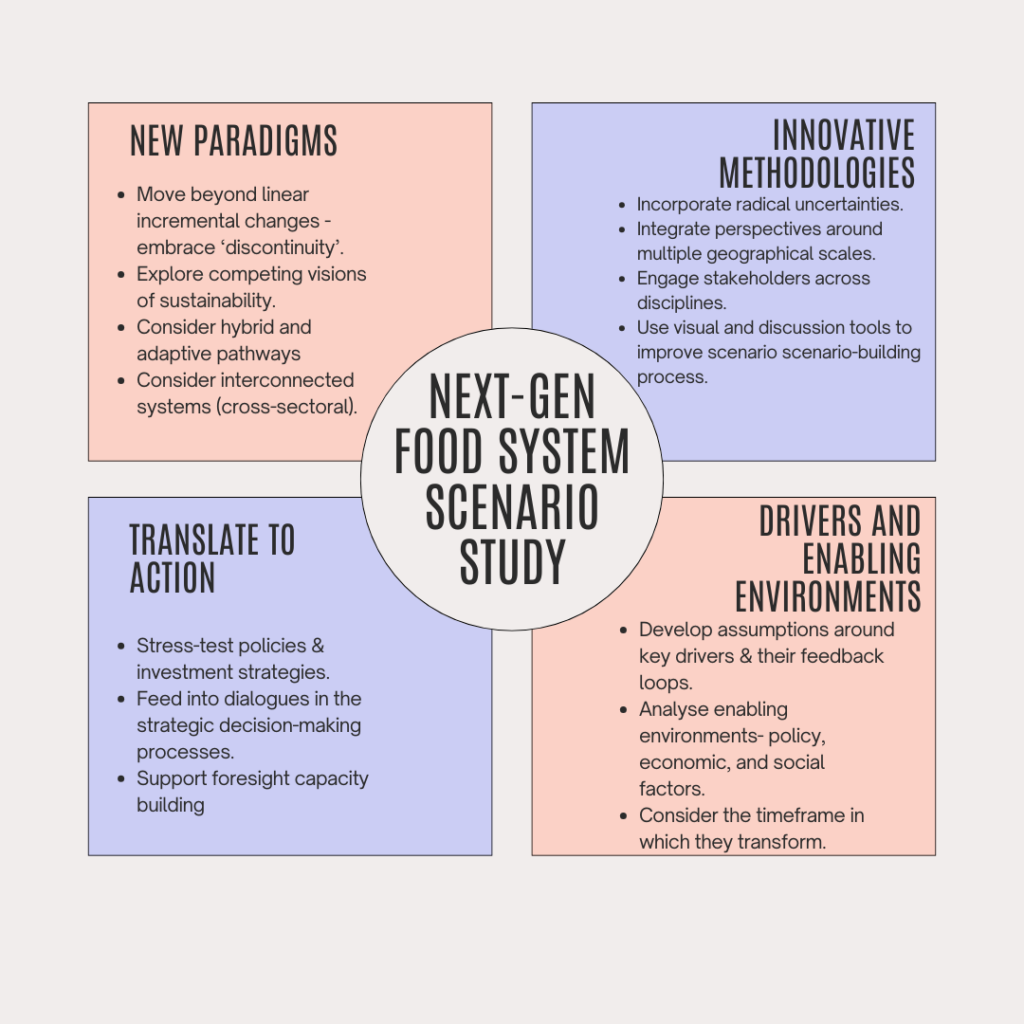

What if the future of our food system looks nothing like what we’ve imagined so far? Our recent report “Food systems of the future” examines how foresight studies are shaping our view of what’s to come. It reveals the urgent need for a new wave of forward-thinking work that dares to imagine fundamentally different food system configurations. Next-generation food system scenarios must embrace a new change paradigm, innovative methodologies, and a clear pathway to incentivise action through a deeper understanding of future drivers and enabling environments.

Why do we need another global-level scenario study?

We live in what many call the acceleration phase of the Anthropocene, an era defined by rapid and unpredictable change. For years, scholars and practitioners across disciplines worked to unravel the complexities of our global food system, using scenarios as vital tools to explore how different forces shape its future. But it’s crucial to remember that these scenarios are not only built on data; our assumptions, beliefs also shape them, and our constantly evolving grasp of the drivers of change[i].

The evolution of food system scenarios reflects this shift. Early models mostly focused on projecting food production and demand based on population growth. Over time, their scope broadened to encompass factors like resource availability, climate change, policy shifts, and socio-economic dynamics. Yet, the turbulent events of the past five years—think of the global pandemic, geopolitical tension, and unexpected supply chain disruption—have shown us that even the most sophisticated scenarios failed to capture certain uncertainties.

Grappling with the multifaceted complexities of the future is undoubtedly a wicked problem. But by continually refining our foresight techniques, we can better prepare for future shocks and proactively design alternative pathways. Let’s explore the critical building blocks for this next generation of global food system scenarios.

1. New paradigms

In Donella Meadows’ view, a paradigm is a shared set of beliefs, values, and assumptions that underlie a system. This core mindset dictates the system’s goals, structures, and operational rules. It follows that a paradigm shift is one of the most powerful drivers of lasting change within a system. For our discussion, there are three aspects that should be considered:

- Discontinuity: Past scenario studies often urged the inclusion of a surprise element or discontinuity[ii] (read box 1 for definition). However, these discontinuities were considered weak in almost all scenarios, especially quantified ones. Instead, scenario studies emphasised continuous incremental changes in the system. Going forward, our scenarios must move beyond a smooth and predictable evolution to explicitly explore non-linear changes, tipping points, and abrupt shifts.

BOX- 1

The term discontinuity is used variously in scenario literature, broadly signifying a sharp departure from past trends caused by high-impact developments, phenomena, and events. The significance of a discontinuity depends on its character, magnitude, speed, and ripple effects, and whether it has been anticipated and ameliorated. Here, a discontinuity refers to a significant shift of social-ecological structure and dynamics, rather than a transient perturbation after which the system reverts to its original trajectory. Related terms are surprises, bifurcation, critical transition, tipping points, tipping elements, wild cards, and black swan events. More recently, the phrase game changers has been introduced for shifts in how society is organized through understandings, values, institutions, and social relationships.

- Mental models: Since the IPCC’s ‘Shared Socio-economic Pathways’, most global scenario studies have relied on a mental model that assumes four broad pathways:

- A sustainable pathway characterised by progressive policy and technological adoption.

- A business-as-usual pathway, projecting a continuation of current trends.

- A collapse or environmental destruction pathway, depicting worst-case outcomes.

- A divided world pathway, where inequalities worsen and cause socioeconomic distress.

While seemingly intuitive the widespread use of this mental model is influenced by cultural biases, cognitive processes[iii], and the culture of scientific reticence[iv] (read box 2 for more). These factors can lead to the design of scenarios that are overly simple, feel intuitively right, and align with common ways of thinking about the future: an optimistic view, a middle ground, and a pessimistic view. We must challenge this reliance on simplistic archetypes and embrace more nuanced and multi-dimensional perspectives in our scenario development.

BOX- 2

Anchoring bias: We tend to rely too heavily on initial information, making it difficult to envision radically different futures.

Confirmation bias: We seek out information that confirms our existing beliefs, reinforcing the status quo.

Incrementalism: We assume change will be gradual and predictable, neglecting the potential for sudden, non-linear shifts.

Lack of interdisciplinary input: Many scenario studies are limited by the perspectives of a narrow range of experts, missing crucial insights from other fields like sociology, ecology, and complexity science.

- Cross-sectoral linkages: Too often, scenario studies operate in isolation, focussing on a single system like food. They fail to incorporate the strong interdependencies with other critical systems such as energy, water, or social systems. This approach can create a lack of understanding of the potential for cascading system failures, or conversely, unexpected positive feedback loops. Future scenarios must explicitly model these intricate interconnections, exploring how changes in one sector can trigger ripple effects across others.

2. Innovative methodologies

Advancing food system scenarios requires leveraging innovative methodologies, for example:

- Multi-scale analysis: Most past food system scenario studies focused on processes at specific geographic scales. Yet food systems operate across a spectrum, from individual households to global markets, with numerous complex inter-dependencies. These dynamics need to be captured in the future studies. The methodology for linking scenarios at different scales was explored by Zurek et al[v]. By integrating local, regional, and global food system dynamics, we gain a more holistic understanding of potential futures.

- Radical scenario development: The scenarios developed in the last decade have often underplayed outlying, surprise, or disaster events[vi]. Yet the inclusion of diverse and radical uncertainties can advance the quality and utility of scenarios[vii]. The development of radical scenarios combines established scenarios with group discussion techniques, as discussed in Talwar et al.[viii]. We need to better embrace wild cards and black swans as integral parts of scenario development, exploring how low-probability, high-impact events can reshape the future.

- Multi-disciplinary expert involvement: Food systems are inherently complex and interconnected, necessitating the involvement of actors across multiple sectors (e.g., agriculture, trade, health, and environment) and governance levels (from local to global). Innovative participatory methodologies such as Transdisciplinary Foresight Labs[ix] and Causal Layered Analysis (CLA)[x] can unpack issues on various levels and uncover underlying assumptions around litany, systemic causes, worldviews, and myths that shape expert opinions. Together, these methodologies support more holistic, inclusive, and imaginative scenario processes.

3. Drivers and enabling environments

Today’s scenarios commonly describe assumptions around the drivers of change (e.g. technological shifts, demand patterns, and trade dynamics). Next-generation studies must go further and reflect on the enabling environments that shape the dynamics of future food system drivers and the timeframe within which the change unfolds. This includes[xi]:

- Policy and governance: How do regulations, institutional capacity, and international agreements shape food system operations?

- Economic and financial structures: How do investment patterns, trade dynamics, and economic inequality influence food access and production?

- Social and cultural context: How do changing consumer preferences, social equity, and cultural norms drive food demand and system practices?

- Technological and infrastructural frameworks: How does digital connectivity, research and development (R&D), and infrastructure development enable or constrain food system innovation?

- Environmental governance: How do policies and practices regarding resource management and climate change impact food production sustainability?

4. Translate to action

Developing next-generation scenarios is not just an academic exercise. To be truly impactful, these studies must bridge the gap between foresight and implementation, ensuring that scenario narratives translate into policy and strategic actions. This involves:

- Using real-world stress tests: Running policies and investment strategies against multiple scenario conditions to assess their resilience.

- Embedding scenario thinking: Integrating foresight and scenario planning directly into decision-making processes at national and global levels. (Read about institutionalising foresight in decision-making in another blog).

- Engaging non-traditional stakeholders: Involving a broader range of voices, including grassroots organizations, indigenous groups, and regenerative farmers, to develop a shared language around food systems and future pathways.

Conclusion

Essentially, the prevailing paradigm in many current scenario studies inadvertently restricts our imagination and limits our collective ability to envision and prepare for truly transformative change. It creates an illusion of control in a world that is far more contingent and unpredictable. The necessary shift towards scenario studies that adequately reflect paradigm shifts is a complex but crucial endeavour, requiring a fundamental rethinking of how we construct and interpret future possibilities.

The food system of tomorrow will not be shaped by predictions, but by our collective capacity to anticipate, adapt, and transform. Advancing next-generation global food system scenarios requires bold thinking, cross-sector collaboration, and an openness to radical possibilities. The question remains: are we ready to embrace this challenge?

[i] Cork, S., Alexandra, C., Alvarez-Romero, J.G., Bennett, E.M., Berbés-Blázquez, M., Bohensky, E., Bok, B., Costanza, R., Hashimoto, S., Hill, R. and Inayatullah, S., 2023. Exploring alternative futures in the Anthropocene. Annual Review of Environment and Resources, 48(1), pp.25-54.

[ii] Rothman, D.S., Raskin, P., Kok, K., Robinson, J., Jäger, J., Hughes, B. and Sutton, P.C., 2023. Global Discontinuity: Time for a Paradigm Shift in Global Scenario Analysis. Sustainability, 15(17), p.12950.

[iii] Cork, S., Alexandra, C., Alvarez-Romero, J.G., Bennett, E.M., Berbés-Blázquez, M., Bohensky, E., Bok, B., Costanza, R., Hashimoto, S., Hill, R. and Inayatullah, S., 2023. Exploring alternative futures in the Anthropocene. Annual Review of Environment and Resources, 48(1), pp.25-54.

[iv] Rothman, D.S., Raskin, P., Kok, K., Robinson, J., Jäger, J., Hughes, B. and Sutton, P.C., 2023. Global Discontinuity: Time for a Paradigm Shift in Global Scenario Analysis. Sustainability, 15(17), p.12950.

[v] Zurek, M.B. and Henrichs, T., 2007. Linking scenarios across geographical scales in international environmental assessments. Technological forecasting and social change, 74(8), pp.1282-1295.

[vi] Gupta, B., Zurek, M.B., Woodhill, J. and Ingram, J. 2025 submitted for publication to Frontiers in Sustainable food systems

[vii] Gordon, D., 2021. Radical Uncertainty: Decision-Making Beyond the Numbers. Quarterly Journal of Austrian Economics, 24(1), pp.206-210.

[viii] https://jfsdigital.org/2019/06/15/the-future-of-energy-reinvented-case-study-of-the-radical-scenario-development-approach/

[ix] Pólvora, A. and Nascimento, S., 2021. Foresight and design fictions meet at a policy lab: An experimentation approach in public sector innovation. Futures, 128, p.102709.

[x] UNDP (2022). UNDP RBAP: Foresight Playbook. New York, New York.

[xi] Gupta, B., Zurek, M., Woodhill, J., Ingram, J. (January, 2025). Food Systems of the Future: A synthesis of food system drivers and recent scenario studies. Foresight4Food. Oxford, United Kingdom.

By Jim Woodhill – Lead Foresight4Food Initiative

It was great to participate in the next phase of Jordan’s journey toward food systems transformation as part of the Foresight4Food Initiative. This significant step brought together around fifty key stakeholders on November 11 to discuss strategies for accelerating change.

The discussions built on earlier work from the Foresight4Food FoSTr Programme in Jordan, including scenario analyses developed during previous workshops, computer modelling results, and a series of policy briefs. These resources provided a foundation for the day’s explorations into actionable pathways for transforming Jordan’s food systems.

A key highlight of the workshop was the collaborative spirit among diverse stakeholders. This environment fostered consensus-building around critical challenges and opportunities. Participants examined deep-seated barriers to change, focusing on economic and social incentives, the power dynamics of various actors, and entrenched mindsets that hinder progress.

Drawing from detailed policy briefs on topics such as vegetable and fruit markets, food governance, the role of the private sector, and the contributions of civil society, the workshop delved into strategies for enabling meaningful change.

Informed by the policy papers on vegetable and fruit markets, food governance, the role of the private sector and the role of civil society, the workshop looked more deeply into how change can be brought about.

One particularly impactful aspect was the use of computer modelling, conducted with Wageningen University and Research’s MAGNET model. This analysis demonstrated the potential consequences of continuing current practices (“business-as-usual”) versus adopting healthier, more sustainable pathways. Such data-driven insights are instrumental for policymakers, equipping them with evidence to support investments and policy reforms.

Beyond the workshop, conversations with Jordanian universities explored integrating foresight and systems thinking into academic curricula. Additionally, a dedicated training session provided researchers and policymakers with hands-on experience using the MAGNET model to analyze food system changes.

The workshops were made possible with support from the Jordanian Hashemite Fund for Human Development (JOHUD) and the National Alliance Against Hunger and Malnutrition (NAJMAH), underscoring the importance of partnerships in driving food systems transformation.

By Jim Woodhill, Lead Foresight4Food Initiative

Why do we need to transform our food system and how can foresight help?

The way food is consumed and produced is central to the polycrisis afflicting today’s world – said Ravi Khetarpal (APAARI), Amina Maharjan (ICIMOD), and Patrick Caron (University of Montpellier) in their keynote presentations at the 4th Global Foresight4Food Workshop.

The Foresight4Food Initiative held its fourth global gathering in the beautiful setting of BCDM Savar, Dhaka from June 3 to 7, 2024. Over 120 foresight practitioners from across 22 countries came together to share ideas and discuss the latest thinking on applying foresight to the challenges of transforming food systems. The event was hosted by the Government of Bangladesh and the Global Alliance for Improved Nutrition (GAIN) Bangladesh, with support from the Food and Agriculture Organization (FAO) and the World Food Programme in Bangladesh.

In a highly interactive week, participants engaged in a masterclass on foresight approaches, shared their experiences and lessons, heard from thought-leaders on food systems and foresight, and identified ways of strengthening foresight practice in their own countries and regions.

What does the future hold for our food systems?

Feeding the world contributes over 30% of greenhouse gases, and without change increasing population and wealth will drive this even higher. Meanwhile, diets are changing, often towards more unhealthy options. It is estimated that, by 2035, diet-related poor health could cost the global economy about 3% of GDP annually: this is the same negative impact that COVID-19 had on the economy. Environmentally, land use associated with food production is the main reason for the world’s massive loss of biodiversity and collapsing ecosystems.

And all of this is set against a background of increasing geopolitical tensions, and uncertainties for trade and access to resources.

As discussed during the different workshop sessions, foresight helps to understand the longer-term consequences of these trends, and the risks of “business as usual”. Even more importantly, participatory foresight and scenario development engages stakeholders in imagining how the future for our food systems could be different, in order to achieve sustainability, equity and resilience.

Highlights of the week included:

- Sixteen case studies on the use of foresight across Africa, Asia and the Middle East shared by participants – offering a wealth of insights, lessons and inspiration.

- Senior-level engagement from the Government of Bangladesh with insight into how foresight is seen as a key tool for helping to achieve their goals for food systems transformation.

- A deeper look at simulation modelling for foresight, and how a combination of qualitative and quantitative approaches can bring a range of important insights.

- Reflections on ensuring foresight processes are inclusive and consider gender dynamics.

- Six thematic sessions on cutting edge foresight issues which helped in mapping out a forward agenda for Foresight4Food.

- Strategic sessions on knowledge platforms and financing of food systems.

- Field trips where participants used insights from food system issues in Bangladesh to stimulate discussion on the future of the food system and sharing of cross-country lessons and experiences.

From my perspective, the key takeaways from the week were:

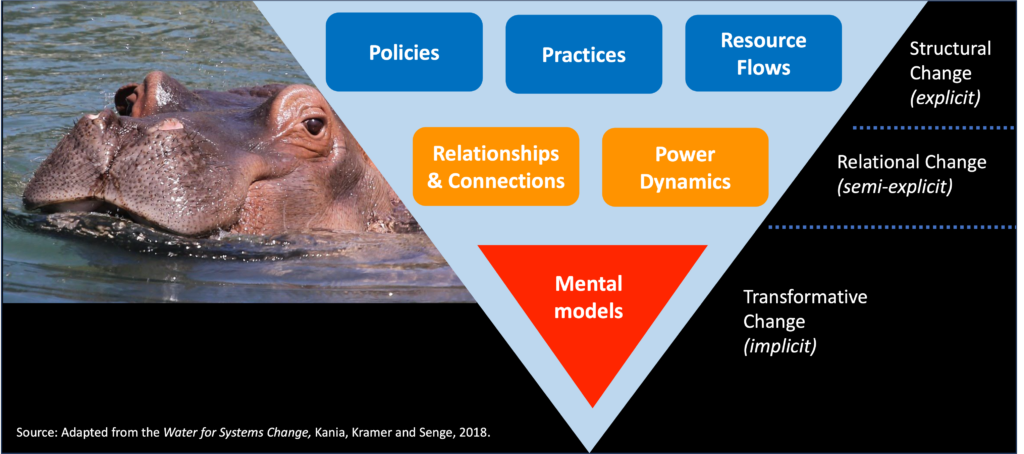

- The value of connecting foresight with a deeper understanding of the political economy of systems change, which is needed to help tackle the structural barriers to transforming food systems.

- Recognition of the critical importance of effective multi-stakeholder processes at national and local levels in driving food systems change, and the value of the foresight for systems change approach in supporting such processes.

- The necessity of increasing and reconfiguring investments in food systems and the need for this to be informed by the longer-term perspectives that foresight can bring.

- The value of integrating participatory foresight processes with quantitative modelling and use of data, while realising the constraints of limited food systems data at national and local levels.

- The importance of having foresight units and processes institutionally embedded in government, with a mandate and scope to challenge policy assumptions.

- A recognized need and growing demand for enhancing the capacities of policymakers, researchers and think tanks/consultants to design, facilitate and use foresight processes.

Participants left highly motivated to take forward the foresight work they are involved in and to help support the Foresight4Food network. The event ended with strong calls for the network to collaborate in helping to set up regional foresight support hubs across different continents.

By Jim Woodhill, Foresight4Food Initiative Lead

Last month (November 2023) I had the wonderful experience of engaging with over fifty young leaders from across Africa, joined by colleagues from Bangladesh, Nepal, and Jordan. We had all gathered in Naivasha, Kenya, to explore how skills in facilitating foresight can be used to help bring about food systems transformation.

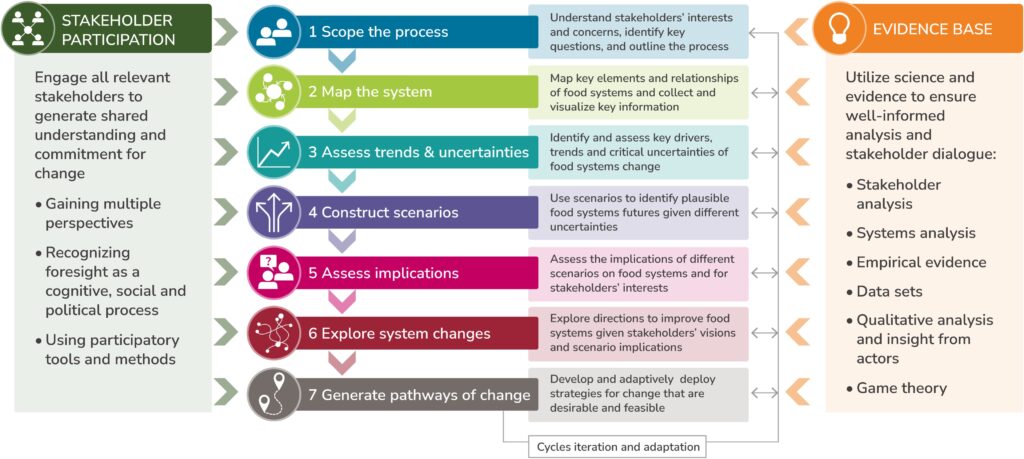

The fascinating work these young leaders are involved in and their deep interest in understanding how to be more effective change-makers was truly inspiring. It was encouraging to see how valuable they found the foresight for the food systems change framework and the associated set of participatory tools for engaging stakeholders.

Participants all came with projects from their own countries where they are keen to use foresight and systems thinking to help facilitate change in food systems by bringing together different stakeholders. The participants were from diverse backgrounds representing policy, the private sector, NGOs, and academia.

A Guiding Framework: During the workshop we introduced participants to an overall guiding framework for facilitating foresight for food systems change. A range of participatory tools were used for systems analysis, development of future scenarios and exploring systemic interventions. To bring reality into the workshop, the Kenya horticulture sector was used as a case study for the foresight analysis. Participants spent a day visiting horticulture farms, packing and processing facilities and the local market. They explored with local stakeholders how they saw the future for the horticulture sector and the issues that “keep them awake at night”.

Visualising the system: The workshop was highly interactive with participants practicing in the facilitation of a range of participatory tools which can be used to bring stakeholders into dialogue around systems change. One of my favourite participatory tools “rich picturing”, which enables a diverse group of stakeholders to develop a shared understanding of a system by drawing it, was found by participants to be especially powerful.

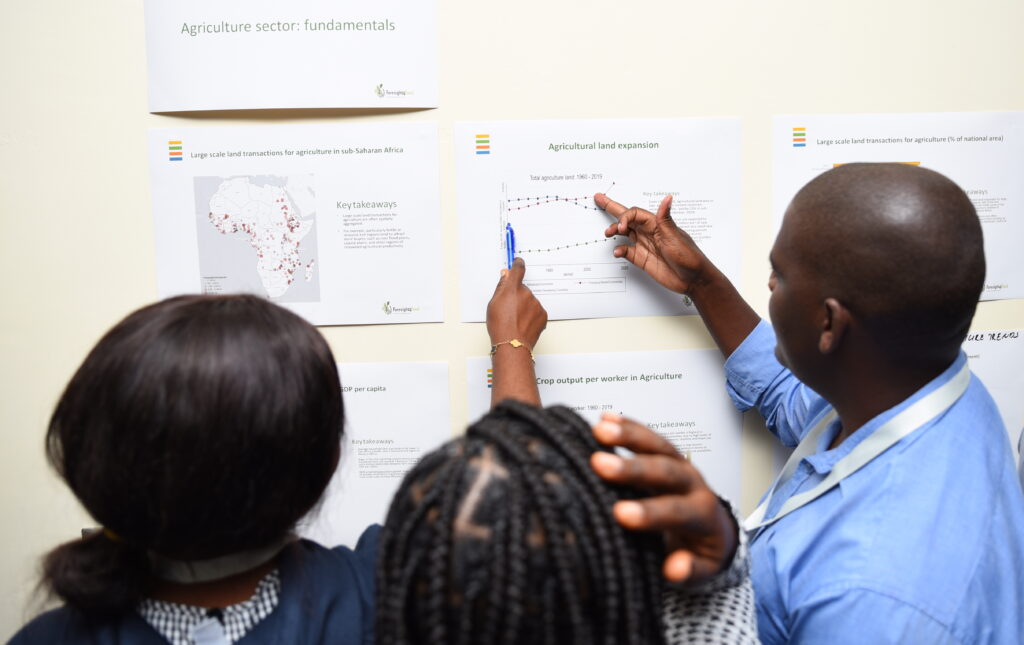

Data-driven dialogue: To go deeper into the systems analysis it is valuable for stakeholders to explore the available data on key drivers and trends. Over 100 graphs visualizing key data points related to the Kenya horticulture sector and food systems at national, continental, and global scales were collated and posted around the walls. The participants then explored this data in groups of three and discussed its implications and how it perhaps challenged their existing assumptions.

Exploring the future using scenarios: Central to the foresight approach is developing a range of different plausible future scenarios (generally with a 10 to 30-year horizon) for how the system might evolve given critical uncertainties. Workshop participants did this for the horticulture sector, looking at factors such as how diets might change in the future, regional and global trading relations, severity of climate change, and the enabling policy environment for small-scale producers and the small- and medium-scale enterprises (SME) sector. The scenarios help to identify future risks and opportunities for different stakeholder groups and society at large. They also help to unlock creative thinking about how to “nudge” systems towards more desirable futures and away from less desirable ones.

The deeper issues of systems change: It is easy to talk about systems change. In reality trying to change systems bumps into all the difficult issues of vested interests, power relations, ideologies, and deeply held cultural beliefs. On top of this human and natural systems are complex and adaptive and behave in self-organising, dynamic, and often unpredictable ways. It doesn’t mean you can’t intervene to try and bring positive change. But it does mean that top-down, linear, and mechanistic models of change generally don’t work. The workshop engaged participants in deep and challenging discussions about what it means to be a leader of systems change. This included the need to be adaptive, how to create alliances for disrupting existing power relations, the importance of building relations between diverse stakeholders, and the importance of patience. Systems change often requires taking time to build the foundations for change without being able to know when circumstances might suddenly unlock opportunities for big steps forward.

Identifying directions for change and intervention options: Developing directions and pathways for systems change is the most difficult and challenging part of the foresight for systems change process. It is highly context-specific and requires a deep insight into the political economy of the situation. Cause and effect mapping, theory of change thinking, and causal loop analysis can all help in identifying opportunities for intervening which could help to drive systems change in desired directions. Bringing change will often require an integrated approach to technological, institutional and political innovation. During the workshop causal loop diagrams were used to explore possible entry points for shifting horticulture systems in ways that could improve health, livelihoods and the environment.

New friends, new networks and big ambitions: After an intense week of learning and sharing participants left inspired to apply the foresight approach back in their own work environment. New friends were made and there were clear calls to find mechanisms to support ongoing networking and peer support.

Many thanks to the facilitation and support team who made a fantastic week possible, Gosia McFarlane, Marie Parramon-Gurney, Kristin Muthui, Bram Peters, Joost Guijt, Riti Herman Mostert, and Abdulrazak Ibrahim. The event was made possible by support from the Mastercard Foundation.

More information about the Foresight4Food Framework of Foresight for Food Systems Change can be found on our website, and an updated approach paper will be published in January 2024.