By Jim Woodhill, Lead Foresight4Food Initiative

Why do we need to transform our food system and how can foresight help?

The way food is consumed and produced is central to the polycrisis afflicting today’s world – said Ravi Khetarpal (APAARI), Amina Maharjan (ICIMOD), and Patrick Caron (University of Montpellier) in their keynote presentations at the 4th Global Foresight4Food Workshop.

The Foresight4Food Initiative held its fourth global gathering in the beautiful setting of BCDM Savar, Dhaka from June 3 to 7, 2024. Over 120 foresight practitioners from across 22 countries came together to share ideas and discuss the latest thinking on applying foresight to the challenges of transforming food systems. The event was hosted by the Government of Bangladesh and the Global Alliance for Improved Nutrition (GAIN) Bangladesh, with support from the Food and Agriculture Organization (FAO) and the World Food Programme in Bangladesh.

In a highly interactive week, participants engaged in a masterclass on foresight approaches, shared their experiences and lessons, heard from thought-leaders on food systems and foresight, and identified ways of strengthening foresight practice in their own countries and regions.

What does the future hold for our food systems?

Feeding the world contributes over 30% of greenhouse gases, and without change increasing population and wealth will drive this even higher. Meanwhile, diets are changing, often towards more unhealthy options. It is estimated that, by 2035, diet-related poor health could cost the global economy about 3% of GDP annually: this is the same negative impact that COVID-19 had on the economy. Environmentally, land use associated with food production is the main reason for the world’s massive loss of biodiversity and collapsing ecosystems.

And all of this is set against a background of increasing geopolitical tensions, and uncertainties for trade and access to resources.

As discussed during the different workshop sessions, foresight helps to understand the longer-term consequences of these trends, and the risks of “business as usual”. Even more importantly, participatory foresight and scenario development engages stakeholders in imagining how the future for our food systems could be different, in order to achieve sustainability, equity and resilience.

Highlights of the week included:

- Sixteen case studies on the use of foresight across Africa, Asia and the Middle East shared by participants – offering a wealth of insights, lessons and inspiration.

- Senior-level engagement from the Government of Bangladesh with insight into how foresight is seen as a key tool for helping to achieve their goals for food systems transformation.

- A deeper look at simulation modelling for foresight, and how a combination of qualitative and quantitative approaches can bring a range of important insights.

- Reflections on ensuring foresight processes are inclusive and consider gender dynamics.

- Six thematic sessions on cutting edge foresight issues which helped in mapping out a forward agenda for Foresight4Food.

- Strategic sessions on knowledge platforms and financing of food systems.

- Field trips where participants used insights from food system issues in Bangladesh to stimulate discussion on the future of the food system and sharing of cross-country lessons and experiences.

From my perspective, the key takeaways from the week were:

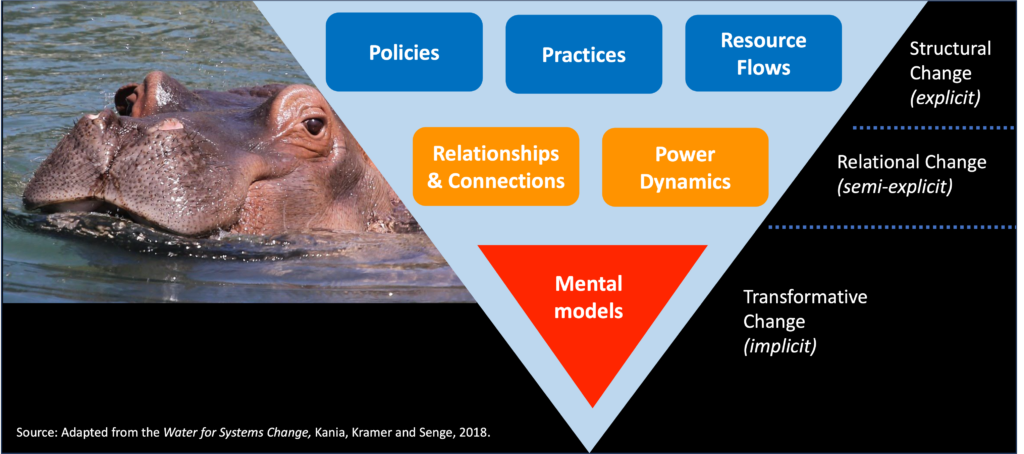

- The value of connecting foresight with a deeper understanding of the political economy of systems change, which is needed to help tackle the structural barriers to transforming food systems.

- Recognition of the critical importance of effective multi-stakeholder processes at national and local levels in driving food systems change, and the value of the foresight for systems change approach in supporting such processes.

- The necessity of increasing and reconfiguring investments in food systems and the need for this to be informed by the longer-term perspectives that foresight can bring.

- The value of integrating participatory foresight processes with quantitative modelling and use of data, while realising the constraints of limited food systems data at national and local levels.

- The importance of having foresight units and processes institutionally embedded in government, with a mandate and scope to challenge policy assumptions.

- A recognized need and growing demand for enhancing the capacities of policymakers, researchers and think tanks/consultants to design, facilitate and use foresight processes.

Participants left highly motivated to take forward the foresight work they are involved in and to help support the Foresight4Food network. The event ended with strong calls for the network to collaborate in helping to set up regional foresight support hubs across different continents.

By Bram Peters

The Foresight4Food FoSTr team has just returned from an active and productive trip to Kenya, despite the challenging political situation in the country. From our perspective, this highlights the need to adapt to turbulence and to use foresight to build resilience for Kenya’s food system.

From June 19 to 26, together with my team members including Jim Woodhill, Herman Brouwer, and Wangeci Gitata-Kiriga we conducted a range of food systems foresight workshops in Nairobi and Nakuru with a wide range of national food systems stakeholders. Here is a brief update on the action.

Navigating turbulence

On the morning of June 19, Foresight4Food, together with partners ILRI–CGIAR, Results for Africa Initiative and University of Nairobi, organised two sessions in Nairobi. The interactive breakfast session was all about ‘Navigating agri-business in turbulent futures’. The session was co-hosted by IFAD Kenya and was attended by a range of private sector associations, business support services, innovation facilitators and impact investors.

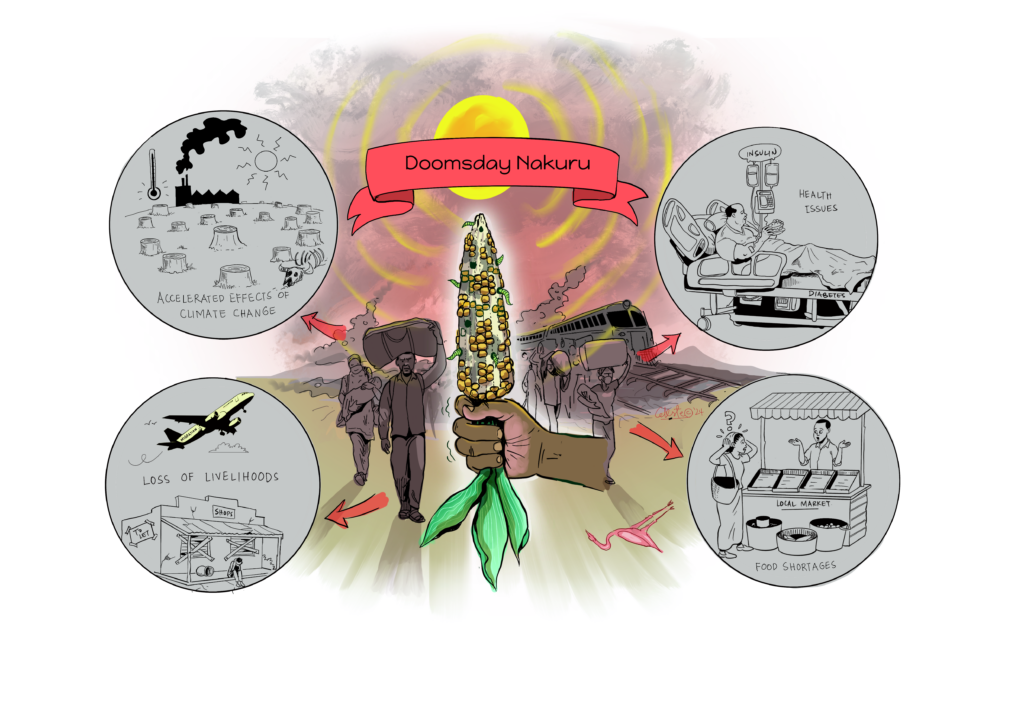

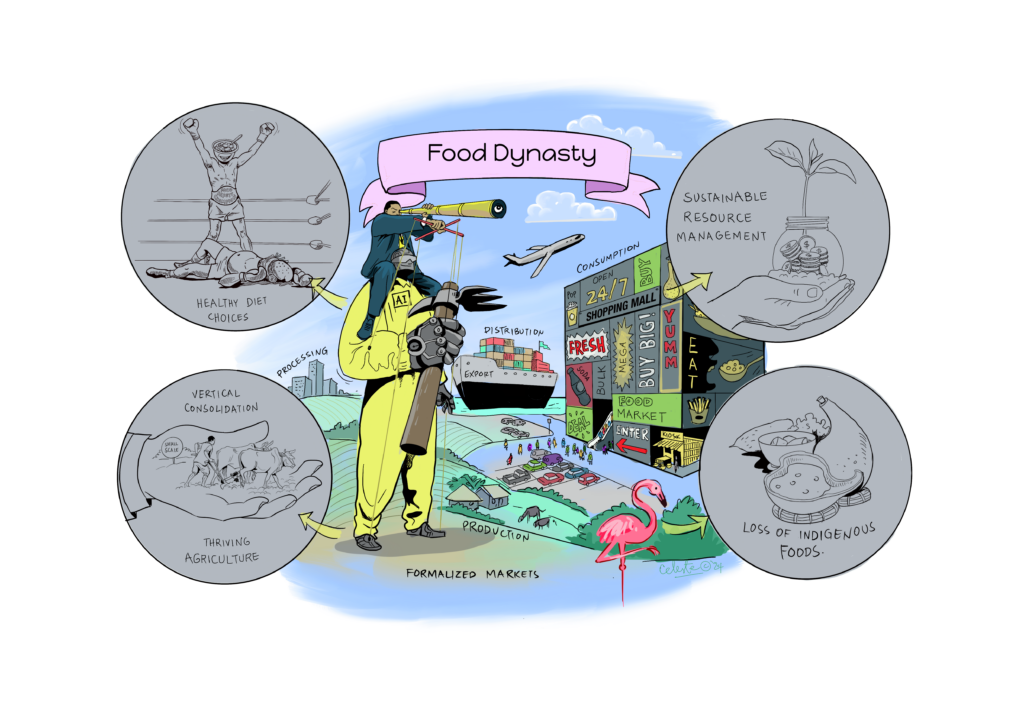

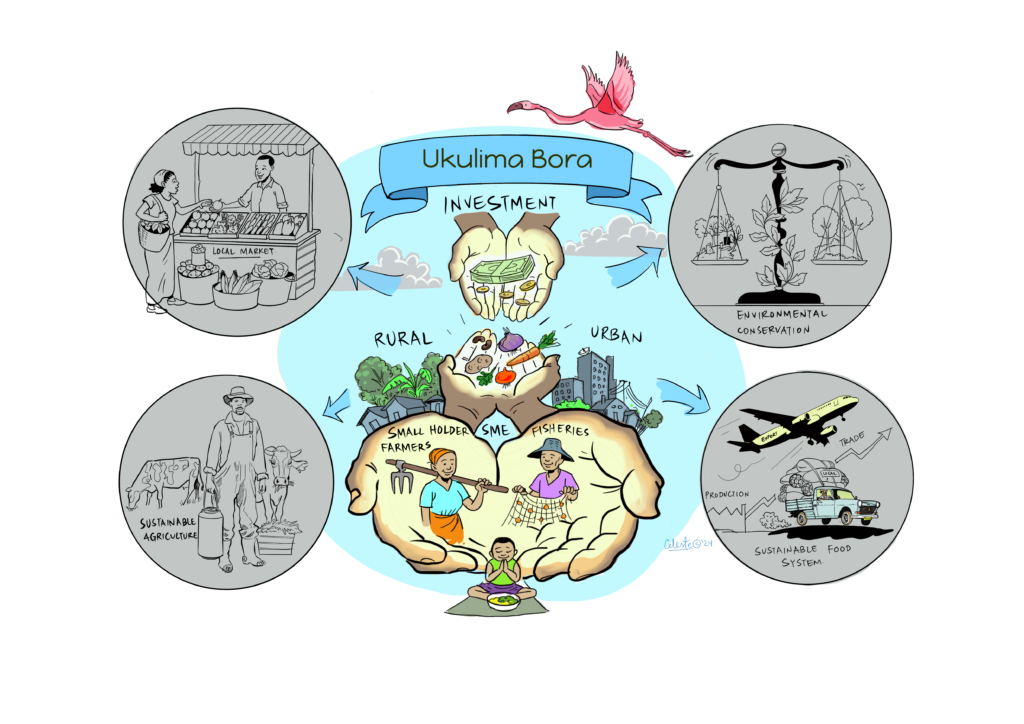

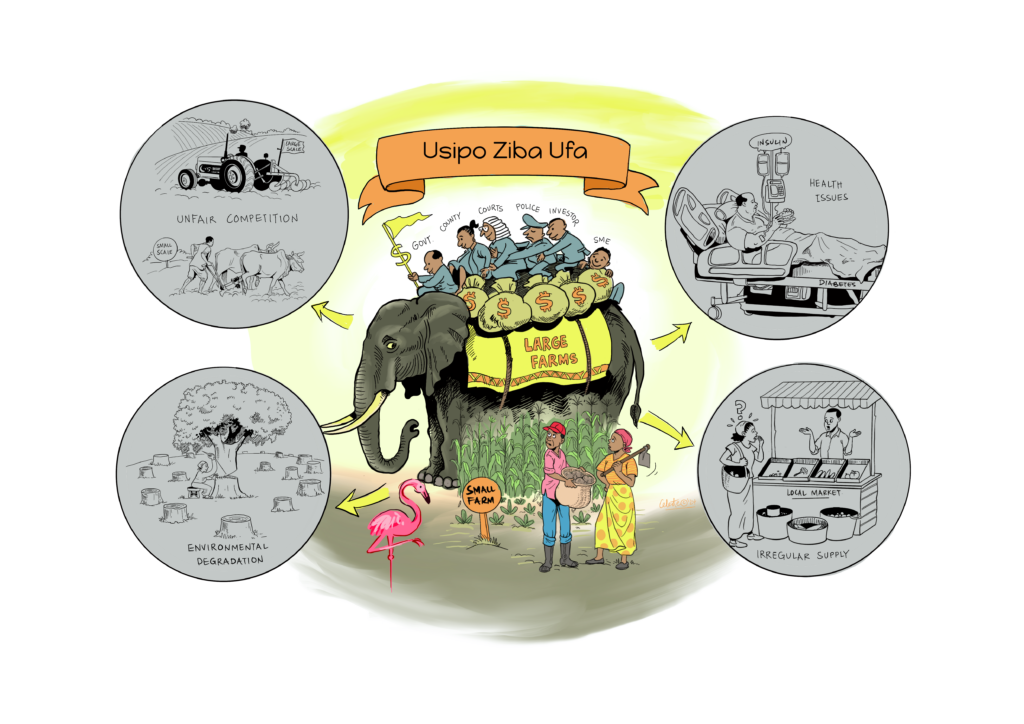

The focus of the meeting was to introduce the topic of foresight in relation to agribusiness in Kenya, share some of the scenarios that were developed in the context of Nakuru, and discuss the implications of different futures of the food system. Participants were shown five different scenarios of how the food system might look in 2040 in Nakuru and were invited to think through and discuss the implications of these scenarios.

With a strong presence and involvement of leaders from various private sector associations such as the Agriculture Sector Network (ASNET) of the Kenya Private Sector Alliance, the discussion invited stakeholders to reflect not only on trends and uncertainties emerging in Kenya, but also how their own businesses are preparing for the future.

Supporting the pathways for food system transformation

In the afternoon of June 19, the FoSTr team organised a national update session on the progress of FoSTr since June 2023. The session was attended by many individuals from the morning session, as well as representatives from government, civil society and research organisations. The FoSTr team presented the latest updates, including the launch of a ‘Kenya Food Systems Mapping Report’, and with a collection of scenarios for the Nakuru food system.

With a special presentation by the Ministry of Agriculture and the Food Systems Technical Working Group and special remarks from IFAD on the 3FS tool, it was discussed how a wide range of ecosystem support initiatives are buttressing the national food systems transformation pathways in Kenya. The approach by Foresight4Food to engage with two counties, Nakuru and Marsabit, and to build on Bottom-up initiatives showed how our approach complements the ongoing national-level initiatives.

Systemic Theory of Change

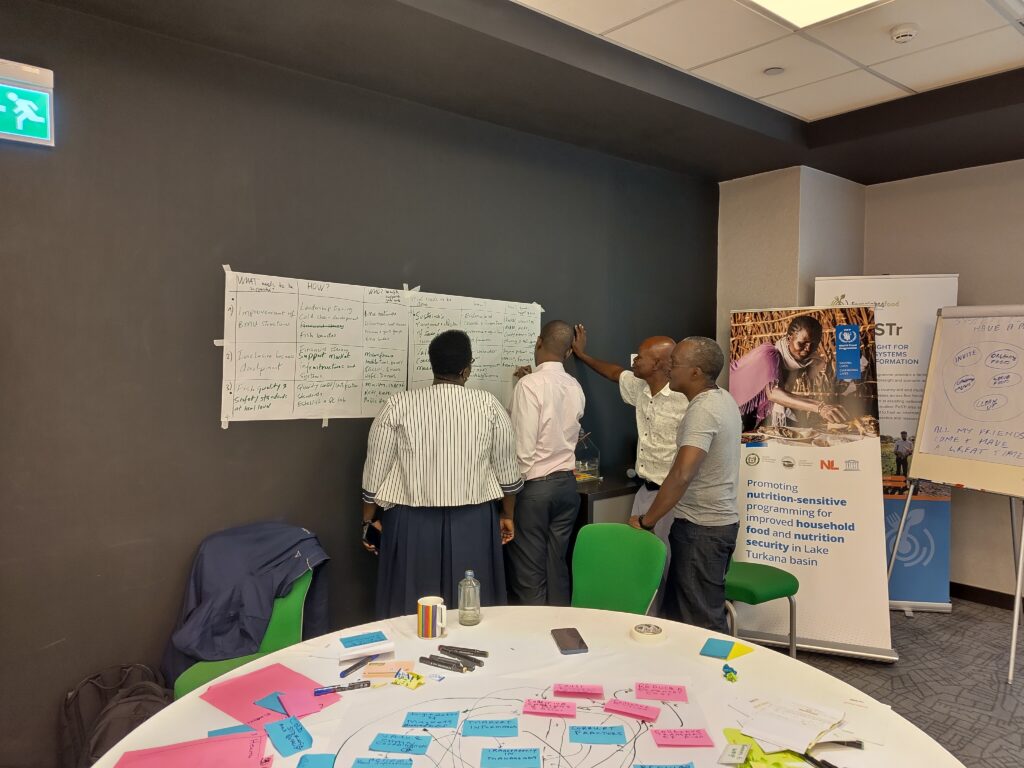

From June 19 to 21, the Foresight4Food FoSTr team facilitated a 3-day workshop for the inception phase of the new Netherlands-funded, World Food Programme and UNESCO on ‘Sustainably Unlocking the Potential of Lake Turkana. Stakeholder representatives from the Lake Turkana region (both on the Marsabit and Turkana sides of the lake) gathered in Nairobi to engage in a shared analysis of the complex food system and co-create the high-level focus of the programme.

The Turkana Lake food system is highly complex, with high food insecurity, vulnerability to climate change and conflict, and many cultural dynamics around pastoralist and fisheries livelihoods. Finding market opportunities and strengthening resilience is not easy, and requires a different way of working. Using the Foresight4Food approach, and building on 6 scenarios that were developed in previous workshops in Marsabit and Turkana, stakeholders explored what might need to be done to understand systemic risks and how lasting opportunities can be triggered.

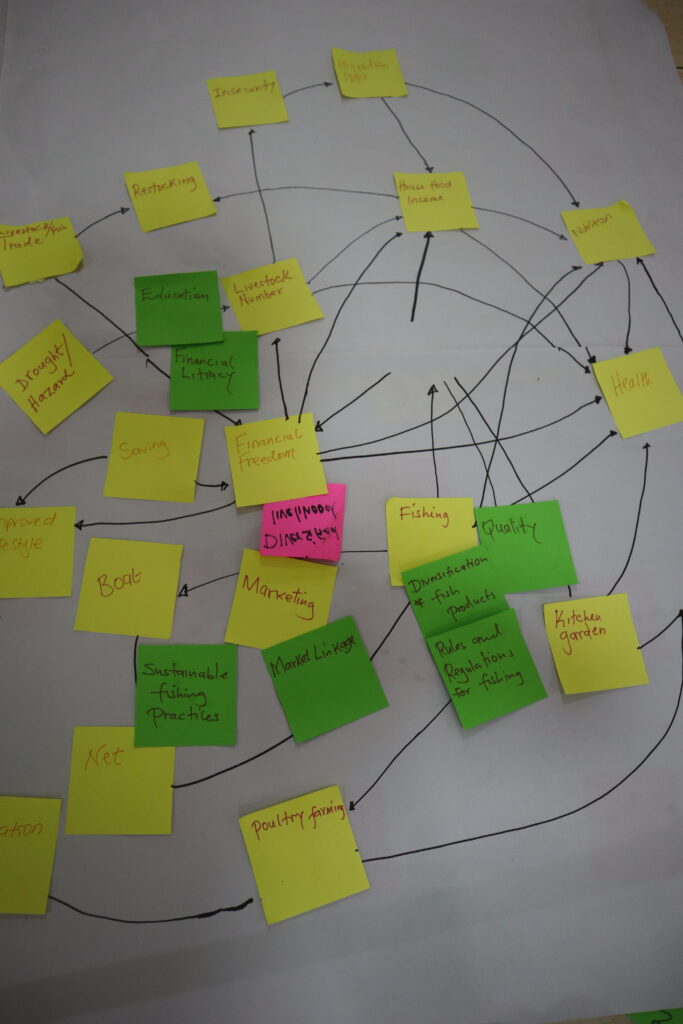

Preparing a Systemic ToC is all about analysing the context, articulating the transformations needed in light of various future scenarios, and developing the building blocks for action. The building blocks include pathways, processes and partnerships. Through many interactive discussions and exercises, the stakeholders conducted value chain mapping of the fish value chain, CATWOVE for articulating systemic change narratives, and Causal Loop Mapping.

Manifesto for Change for the Nakuru Food System

On June 24 and 25, the FoSTr team including partners ILRI-CGIAR, Results for Africa Initiative and University of Nairobi once again visited Nakuru, now to explore systemic change pathways. As we already noted from previous workshops, the food system of Nakuru County is full of potential, as Nakuru’s natural resources are rich and a wide range of agricultural value chains are represented. However, challenges related to food and nutrition security and environmental sustainability exist. Trends of climate change, unhealthy diets and land fragmentation are appearing. The future holds many uncertainties. In order to future-proof the food system, it is urgent that investments are made to further enhance the resilience and sustainability of food and agriculture in Nakuru.

Since November 2023, a diverse group of more than 40 different stakeholders from Nakuru county have been coming together to consider the future of food system, supported by researchers and facilitators of Foresight4Food. This inclusive group looked at the challenges and opportunities for food and agriculture today and how they might evolve in 10-15 years. Food system analysis, an assessment of drivers and trends relevant to Nakuru, and 5 scenarios were developed by this group.

During these two days, stakeholders from Nakuru engaged in scenario interpretation and Causal Loop diagramming to come up with key pathways to kickstart food system transformation in Nakuru. These outputs culminated in a Manifesto for Change: a vision for the desired future for Nakuru’s food system and a range of possible pathways that can set us in that direction, while preparing us for a range of uncertainties. The Manifesto calls upon all stakeholders to join and align their actions, and intensify collaboration to transform Nakuru’s food system so that it can feed its people nutritiously; advance economic development; restore balance with nature; grow in-county revenue and eventually GDP growth for Kenya.

By Zoe Barois

Over the past year, the Foresight4Food Foresight for Food System Transformation – FoSTr team and our country partners have begun a foresight process in Jordan, Uganda, Kenya, Bangladesh, and Niger to support national food system transformation. As an initial step, a collective understanding of the food system in different contexts was needed. Hence, the Foresight4Food team in collaboration with our facilitators and research partners in each focus country, created comprehensive food systems reports mapping the dynamics, trends, drivers, and activities within the food system.

Being a lead on food system mapping, I’m sharing my reflections on the process in this blog.

We started with a scoping phase using the Foresight4Food foresight framework, which allows for flexibility and contextual adaptation. This phase involved identifying key stakeholders, understanding their interests, and assessing current and future concerns.

Our next goal was to foster a shared understanding of the food system’s key dynamics, outcomes, drivers, and activities to identify trends and uncertainties. This collective understanding forms the foundation for a participatory process using foresight and scenario analyses to support meaningful food systems change.

The second step, system mapping, was done in collaboration with country facilitators and research teams. We used the Foresight4food framework to identify key food system outcomes, activities, and drivers, considering their interaction with the broader environment. Data were compiled from national and global sources and generated through participatory workshops.

In addition to providing an overview of current status and trends, we conducted a deeper analysis using causal loop diagrams created with research partners during workshops. This approach helped identify trade-offs and synergies, informing actions to improve food system outcomes. We also noted recurring patterns that affect feedback loops, further clarifying the system’s structure.

These reports offer an initial snapshot of the current food system status and are intended to inform a more comprehensive foresight process. As the dynamics, trends, drivers, and activities within the food system continually change, these reports welcome ongoing reflection and discussion.

Read and download reports

The global food system needs to be transformed. It needs to deliver better health and improved livelihoods while protecting the environment and minimizing negative social impacts.

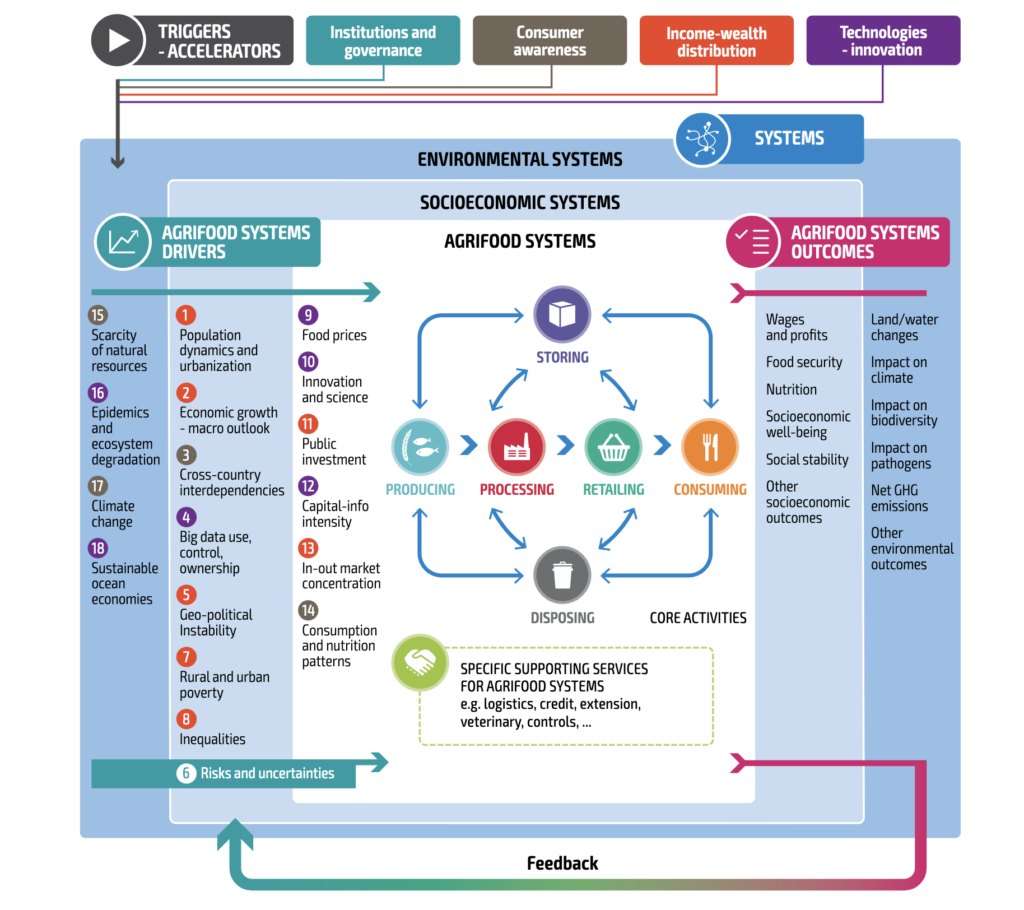

However, there are many interconnected factors playing a role. Food Systems are complex adaptive systems which require a deep analysis of their various driving forces and dynamics. They are shaped by a multitude of interconnected factors or drivers, some well-defined, others with a lot of uncertainties with them. A recent study by Forsight4Food identified the most critical drivers of the global food system as described by a set of 19 recent foresight reports. It was not easy to define and categorize these very drivers, and we will also discuss these challenges in this blog.

The Entangled Web of Drivers

Many studies, from the 2003 Millennium Assessment report to FAO 2022 have defined what is a ‘driver’. But the challenge is the lack of a universally agreed-upon definition for a driver. This means that categorizing these drivers is problematic. For instance, they can be classified based on their relationship with other drivers (direct or indirect), external factors (like PESTLE analysis- Political, Economic, Sociological, Technological, Legal and Environmental), or the extent of our knowledge about them (known knowns or unknown unknown).

What makes it even more intricate is that, due to the systemic nature of the food system, its nutrition, environmental condition, and economic development outcomes feedback indirectly becomes driver themselves. This creates feedback loops that complicate pinpointing which drivers are truly direct and which are indirect. Ultimately, it depends on the specific part of the system you’re focusing on. This is nicely depicted in the FAO’s food system diagram, however, it does not show the interconnections between different factors which is what needs careful consideration.

Source: FAO 2022

Here’s another layer of complexity: There are “known knowns” drivers like climate change and population growth and many models have been developed to understand the future trend. Then there are drivers such as government interventions (trade policies and subsidies) which is undoubtedly an important driver, but predicting the future impact of specific interventions is challenging. Similarly, we understand that diets are shifting towards more protein, but whether this trend holds true depends on the specific scenario we’re considering. These are “known unknowns” – we know they exist, but their future impact is a mystery. But the complexity is even deeper: “unknown unknowns”. Take the influence of social media on food choices. This is a relatively new area of study, and its full impact on the food system remains unclear. There can be overlaps in any type of categorisation system. Therefore, it is important to involve experts at this stage.

Identifying the Critical Few

The next hurdle is identifying “critical drivers” – those with the most significant potential to impact the food system. These drivers can influence various stages through established historical trends or emerging uncertainties. A key challenge lies in determining their relative importance across diverse contexts, often depending on stakeholder perspectives. For instance, immigration policies can have a significant impact on agricultural workforces in some regions. Incorporating stakeholder consultations is crucial to prioritize the most impactful drivers in these specific contexts.

Keeping the Conversation Open

It’s vital to remember that the impacts of drivers manifest differently across various socio-economic settings and among different food systems stakeholders. Highlighting the context in which a driver is critical helps us develop more targeted solutions.

We must also acknowledge that new or emerging drivers with unclear trends can also have profound impacts. For example, as mentioned earlier, the role of social media in influencing food choices is a relatively new area of study.

Therefore, the conversation around identifying critical drivers needs to be open to periodic updates. As we uncover new information and witness the emergence of new drivers, we can refine our understanding of the food system and adapt our strategies accordingly.

Future Trends and Projections

The future trajectory of these drivers is influenced by various factors, both internal and external to the system. Climate change, consumer behaviour, and technological advancements all play a role in shaping the path ahead. These complexities of cross-impacts create uncertainties about the future, often interpreted through different assumptions in various projections.

Many reports from IPCC, FAO and UNDP present some of the trends and projected trends around food system drivers. But these vary due to the underlying assumptions. Moreover, deciphering these projections can be challenging due to two key factors: 1) varying timescales and 2) diverse representations of what a sustainable food system actually looks like. However, by delving deeper into these assumptions and comparing them, we can gain a more comprehensive understanding of the possible futures that lie ahead.

What we found…

The review of recent studies on food system drivers revealed a mix of established and emerging influences. We categorised drivers using the known-knowns and known-unknowns classification. Long-standing factors like demographic changes, climate issues, technological innovation, resource efficiency, socio-economic inequalities, government interventions, health considerations and level of connectivity continue to shape food systems, while new drivers such as the rise of e-commerce post-COVID-19, concerns about power imbalances in food value chains, labelling and packaging, data ownership issues, the role of indigenous knowledge, labour migration policies and perceptions around vegan and vegetarian diets are gaining importance. The relevance of these drivers varies based on stakeholder perceptions, indicating the diverse issues decision-makers must consider for effective management and adaptation.

The review also noted varying levels of uncertainty associated with these drivers. Established drivers, such as demographic trends, have narrower uncertainty ranges due to extensive research, leading to more consistent projections. However, differences in time frames, methods, and assumptions among studies complicate direct comparisons of quantitative trends. Emerging drivers, like government interventions and social media’s influence on consumer behaviour, exhibit broader uncertainty ranges and diverse trend directions, making them particularly significant for developing future scenarios. Our upcoming report will discuss these critical points in detail.

Conclusion

Transforming global food systems to deliver better outcomes is a complex and urgent challenge. Understanding the critical drivers shaping these systems, both well-known and emerging, is essential for creating the societal understanding and political will needed for meaningful change. Just as a map evolves with new discoveries, our understanding of these critical drivers needs constant refinement. Through ongoing research, collaboration, and open communication, we can navigate the complexities of the food system and support targeted solutions towards a more sustainable food system.

The preparations for the 4th Global Foresight4Food Workshop are well underway. A diverse group of participants are expected to join and use this opportunity to share their ideas and insights as well as connect with a growing community of foresight practitioners. In regard to this, we asked Dr. Rathana Peou Norbert-Munns, Sustainable Development, Agrifood System Policies and Climate Foresight Planning Specialist at FAO and a valuable member of the Foresight4Food steering group to share some thoughts and her expectations from the workshop.

The biggest challenge our world is facing that keeps me up at night…

If I had to pinpoint the most significant challenge, it would undoubtedly be climate change. However, as a foresight planning specialist, I’d say that a forward-thinking planning approach helps various stakeholders recognize not only the widely acknowledged issues but also those that are just beginning to emerge, the so-called early signals. These insights enable us to map out risks across multiple time horizons and envision plausible futures and encourage us to rethink our current actions and adopt innovative approaches which are urgently need it. Ultimately, while these concerns sometime disrupt my sleep, it definitely fuels my daily actions with a clear, long-term vision for sustainable change.

What I look forward to in the 4th Global Foresight4Food workshop

My expectations are set high to leverage the tool of Foresight for Food System Transformation effectively. In a global polycrisis, there is a pressing need for innovative and strategic thinking to guide decisions that ensure sustainable food systems.

This year’s theme of the Foresight4Food Global Workshop captures the essence of what we aim to achieve: a shift in how we envision and shape the future of food systems. It promises to be a crucial platform for sharing insights, fostering collaborative efforts, and enhancing the capabilities of practitioners through knowledge exchange and community building. It is an opportunity to connect with a diverse network of experts and stakeholders, all driven by the common goal of transforming food systems for a better future. By creating a safe space for discussion and reflection, the workshop will challenge us to consider innovative accelerators for our work and identify necessary changes in our approaches.

“This year’s theme of the Foresight4Food Global Workshop captures the essence of what we aim to achieve: a shift in how we envision and shape the future of food systems.”

The workshop will also allow us to critically assess vested interests within the food systems, ensuring that our solutions are inclusive and equitable, truly embodying the principle of leaving no one behind.

On a personal level, I expect that the insights I’ll gain from the workshop will be integral to refining approaches developed for key programs in the Asia Pacific region. By learning the latest foresight methodologies and emerging trends, I aim to reflect with an increasing community of practitioners and find avenue to collaborate more effectively with stakeholders to implement resilient and sustainable food policies and practices.

Some ways to make the workshop more effective, my two cents

To ensure the workshop has a lasting impact on cross-sector collaborations and actions towards food system transformation, Foresight4Food must foster an environment of honesty where participants feel secure in openly sharing both challenges and innovative ideas. Encouraging creative and bold thinking is essential, as it will drive the development of groundbreaking strategies that transcend traditional sector boundaries and catalyze meaningful changes through transformative foresight.

Foresight4Food is organizing its 4th Global Workshop in June titled “Reframing Food Futures: Making Foresight Transformative”. To raise the tip of the curtain on this exciting event, we have asked Mohammad Monirul Hassan, Foresight4Food Country Facilitator and Global Alliance for Improved Nutrition (GAIN) Advisor, to share some of his thoughts and expectations. Here is what he has to say:

As a food systems practitioner, what keeps me up at night

Bangladesh has made significant progress in food security and nutritional status over the past decade, with a growth rate of food production much higher than population growth. The country’s food grain production self-sufficiency has been sustainable and stable, and access to food has improved over time. However, the country still faces challenges in ensuring food and nutrition security for its growing population of around 170 million, projected to reach over 186 million by 2030.

The recent COVID pandemic and the subsequent Russian-Ukraine war have put enormous pressure on the food supply in the country, as Bangladesh is a net food importing country. We have achieved self-sufficiency in rice and some other products; however, the country is still dependent on wheat imports, edible oil, lentils, pulses, and spices. Due to the depreciation of Bangladesh’s Taka against the US Dollar, import costs have increased significantly which impacted the price of commodities both in the food and non-food sectors. The lower-income households are struggling to meet daily needs due to income losses and price hikes.

As a Bangladeshi citizen and a food systems practitioner, a thought that concerns me is that the emerging negative trends and uncertainties like climate change, population growth, income inequality, agricultural labor scarcity, and barriers to access to safe and nutritious food may push back the decade-long achievement of the food and nutrition security of the country in the long run.

Climate change adaptation is the key priority in Bangladesh. Bangladesh is one of the most vulnerable countries in the world to climate change impacts. Developing climate-resilient technologies that exhibit tolerance to drought, flood, heat, cold weather, and salinity can help mitigate production losses caused by the frequent occurrence of extreme weather patterns anticipated due to climate change. Alongside conventional staple crops like rice, wheat, and maize, more focus is given to advancing technologies for protein-rich crops such as pulses and beans, as well as vitamin-rich fruits and vegetables. Enhanced breeds of cattle and poultry that possess the ability to endure harsh climatic conditions are being developed.

The focus is given to enhancing productivity through advances in crop, livestock, and fisheries management, either individually or in combination with genetic enhancements. Improved management methods in agriculture can enhance profitability for producers while also promoting sustainability by optimizing the use of inputs such as seeds, fertilizers, pesticides, and water, and lowering the environmental impact of farming. To improve the food and nutritional situation, more emphasis needs to be placed on coordination, enhancing partnership and policy coherence, and strengthening implementation means.

FoSTr’s support in Bangladesh’s vision of sustainable food systems

Food system transformation is high on the political agenda in Bangladesh with the formulation of the National Food and Nutrition Security Policy 2020, its Plan of Action (PoA) 2021-2030, National Agricultural Policy 2018, and Bangladesh’s contribution to the UN Food System Summit 2021 and the UNFSS +2 Stock Taking Moments (STM). Bangladesh has outlined its “Making Vision 2041: A Reality-Perspective Plan of Bangladesh 2041”, Dhaka Food Agenda 2041, Smart Bangladesh Vision 2041, and the Bangladesh Delta Plan 2100, which depict the country’s aspiration and preparation towards a developed nation.

To support that, the Foresight for Food Systems Transformation (FoSTr) program is providing a flexible decision-support facility to support Bangladesh with evidence-based foresight and scenario analysis that goes along the country’s vision to work towards sustainable food systems in Bangladesh.

As part of reporting to UNFSS STM+4 (2025) and fulfilling the Honorable Prime Minister’s commitment to UNFSS, foresight analysis of the food systems will complement the data, research, risk analysis, and scenarios development for the future food systems and provide necessary guidance for food systems transformation.

Expectations of the Foresight4Food Global Workshop experience

For this year’s Global Foresight4Food Workshop, the theme is “Reframing Food Futures: Making Foresight Transformative”. What I seek from this workshop is an opportunity for cross-country learning about using foresight tools, their drawbacks, and ways for improvement for better foresight analysis, as well as areas of collaboration, partnerships, and future investments for the country’s food systems transformation. I also think this will be a wonderful opportunity to showcase how Bangladesh is transforming its food systems with its various challenges.

From a personal point of view, I expect that the learning and insight of the workshop will help me understand the food systems transformation agenda in Bangladesh. It will also help me in policy advocacy in prioritizing areas and activities that build sustainable and resilient food systems.

Another aspect of the Foresight4Food Global Workshop that I hope for is that it will create space for highly interactive dialogue, igniting creativity and sparking actionable progress on the foresight agenda, offering cutting-edge updates on foresight practice and applying foresight to country realities.

The workshop will contribute to understanding how other countries are transforming their food systems, what works and what doesn’t, what matters most, and what supports are required, etc. The workshop will be a great opportunity where you’ll be able to build networks, partnerships, investment opportunities, and investment progress tracking and implementation. Moreover, the workshop will help governments reframe some of the initiatives and prioritize them based on the political economy contexts.

All in all, it will be truly exciting to see energetic participation from food systems researchers, practitioners, and government and private sector representatives gathered under one roof to talk about making foresight transformative.

By Bram Peters – Food Systems Programme Facilitator, Foresight4Food

In the north of Kenya, on the border with Ethiopia, the landscape is expansive and dry. Pastoralism is the main source of livelihood, but to the west of this landscape is Lake Turkana, one of the largest saline desert lakes of the world. Here communities engage, some productively and others reluctantly and out of desperation, in fishing.

In March 2024, the Foresight4Food FoSTr team traveled to the fascinating Kenyan county of Marsabit to facilitate a multi-stakeholder forum to support the co-creation of the new ‘Sustainably Unlocking the Economic Potential of Lake Turkana’ programme.

In Marsabit, stakeholders from around the Turkana Lake, including fishers, traders, service providers, county government technical officers, and non-governmental organizations, came together to analyze the context and co-create future scenarios and intervention areas for a new WFP and UNESCO programme, funded by the Embassy of the Kingdom of the Netherlands.

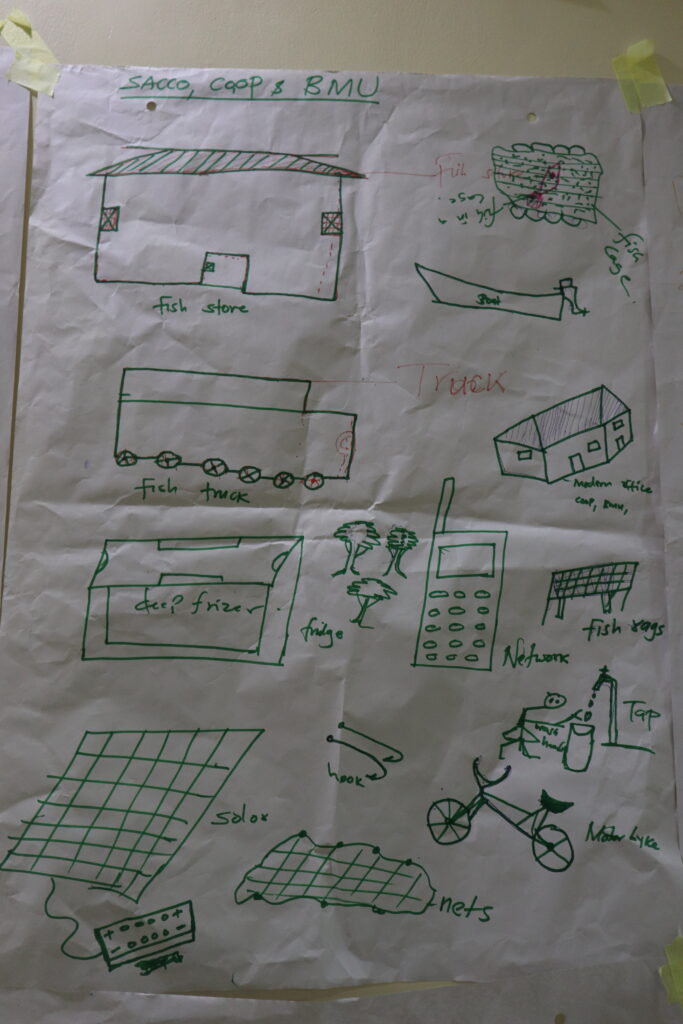

Together with the World Food Programme and the World Food Programme Innovation team, the FoSTr team held a highly interactive and productive three-day workshop. As most stakeholders mainly spoke Kiswahili, we switched to short presentations with much emphasis on interactive group work. On the first day, the workshop focused on contextual understanding of the Lake Turkana food system as well as the Marsabit county livelihoods, using the Rich Picture mapping exercise. Participants together drew the food system, the geography of the lake, but also the stakeholders, activities, key relations and dynamics.

On the second day, the groups presented their deep knowledge of the context to each other and elaborated on this. Workshop participants tackled key trends shaping the food and livelihoods system: groups discussed how various themes (for example: lake water levels, fish stocks to income sources, conflict, and education) changed over time and what they expect to happen 10 years into the future. Important in this discussion is their analysis of what driving issues would influence change in the future.

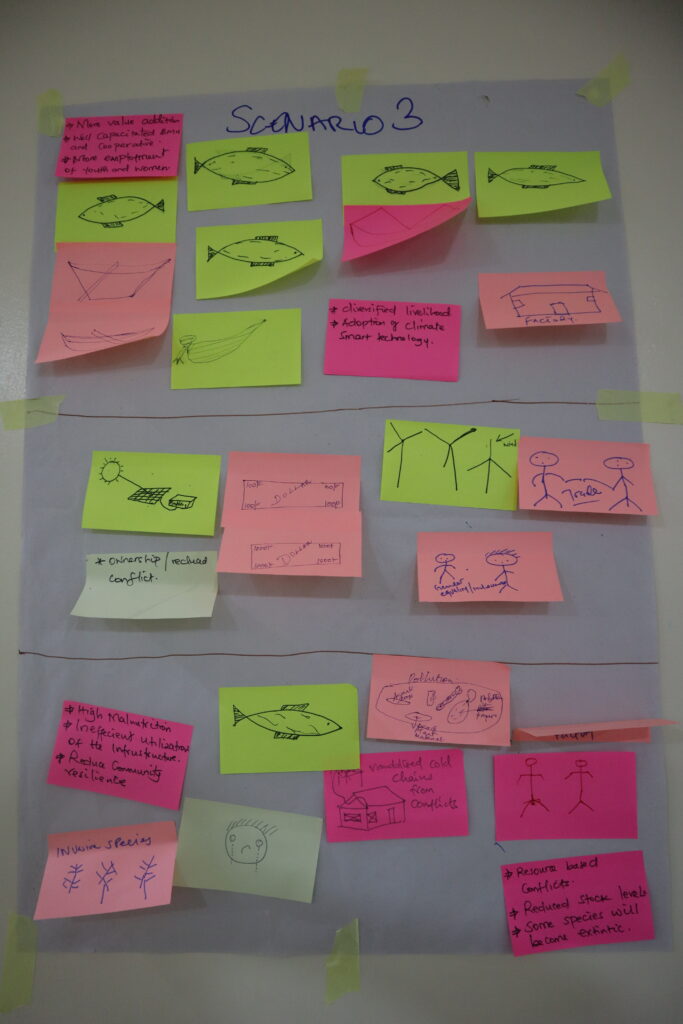

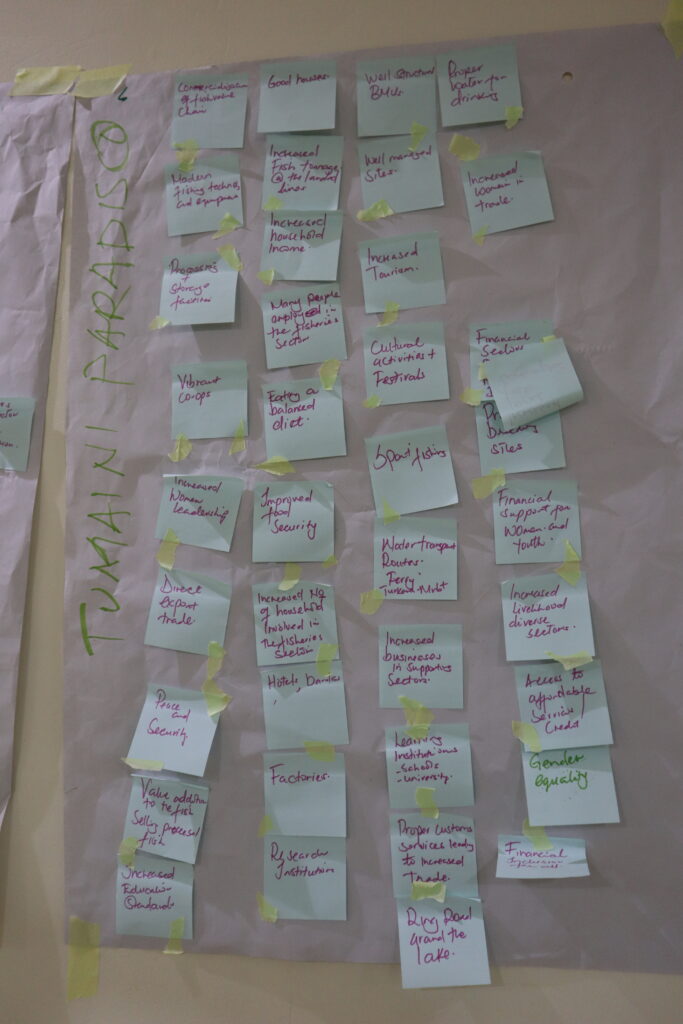

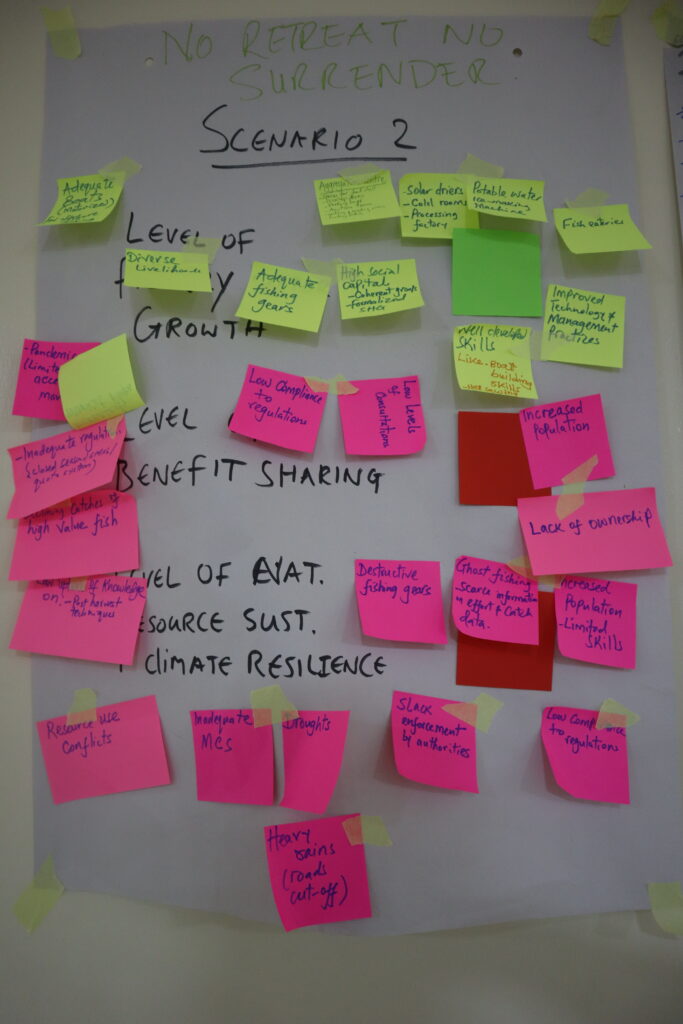

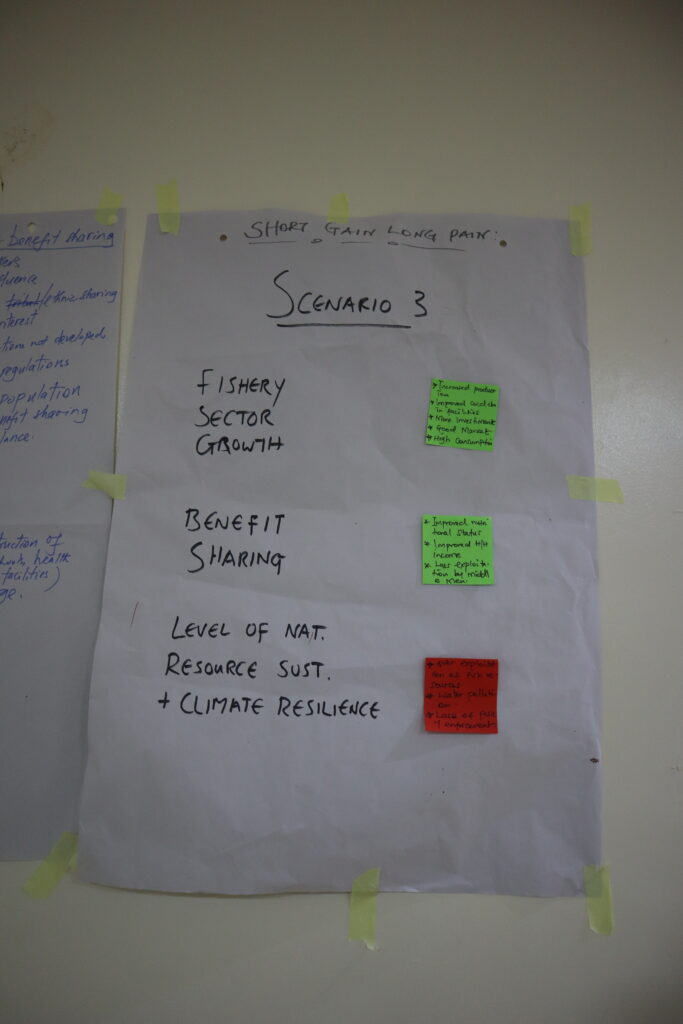

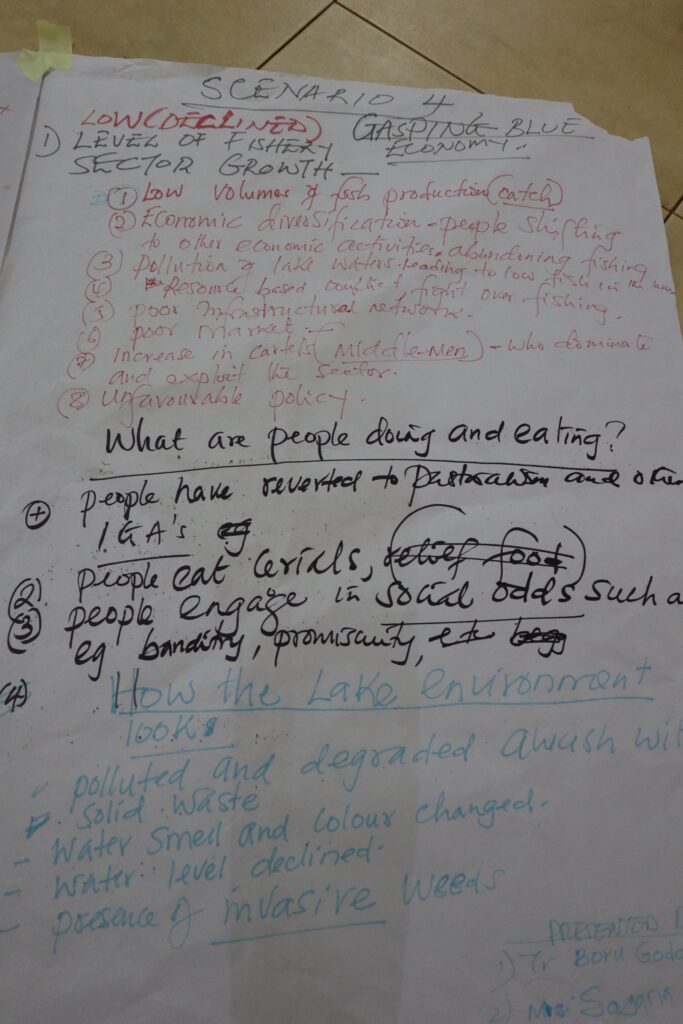

5 scenarios were created for the future regarding the fisheries sector and supporting livelihoods, as well as an in-depth discussion on key entry points for intervention in the system. These scenarios had names that described these futures succinctly:

- ‘Tumaini Paradiso’, a future with a growing fishing sector, inclusive benefit sharing and sustainable natural resource management;

- ‘No retreat, no surrender’, a situation in which the benefits of a growing fisheries sector are controlled by a few;

- ‘Short gain, long pain’, a scenario where the fisheries sector grows and livelihoods improve around the lake, but the environment is not maintained;

- ‘Gasping blue economy but others rise’, is a future where the fisheries sector remains marginal for communities, but other sectors are developed that also contribute to inclusive development and environmental sustainability

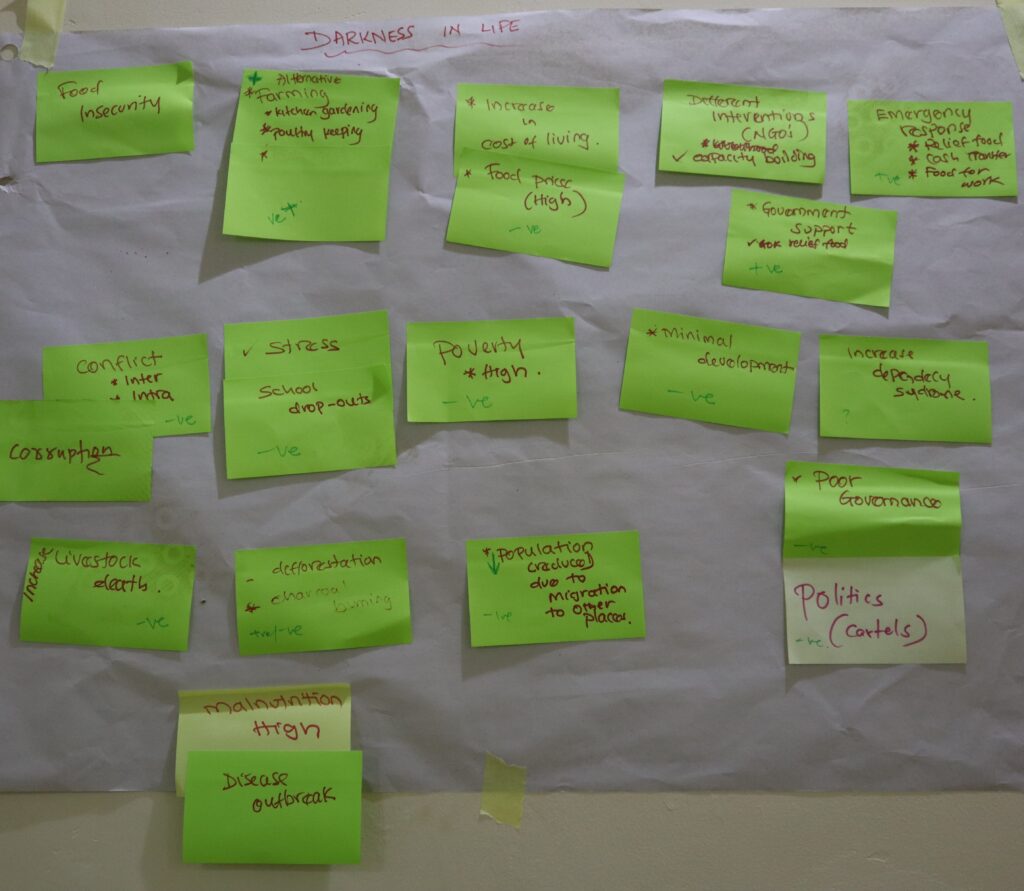

- ‘Darkness in life’, a bleak outlook where none of the envisioned sustainable economic development around the lake delivers and where climate resilience is low, and conflict is rife.

Different stakeholders participating in the workshop had different opinions on the likelihood of certain scenarios emerging. Some imagined the situation worsening, while a few viewed the future more positively. These reflections clearly showed a combination of outlook of participants as well as the signals they interpret from the current situation and the trends seen now. Interestingly, none of the stakeholders felt the ‘Paradiso’ scenario was likely, showing that the programme needs to be modest in its systemic ambitions, but also be ready to do things very differently. These scenarios showed what could become a very relevant frame of reference to the stakeholders as well as the programme implementors.

On the last day of the workshop, participants explored a common vision for the future, and how the food system is currently working. This led stakeholders to have a first try at exploring what is needed to change that system toward the common vision.

At the end of the workshop, I felt highly positive about these fruitful discussions that enabled participants to think about what might happen to the Marsabit food system in the years to come, and what factors would influence these changes. In addition to that, the insights gathered through the multi-stakeholder forum are expected to not only support the inception phase of the programme but will also support multi-stakeholder engagement throughout the programme.

The Foresight4Food FoSTr team will continue to support the World Food Programme team in realizing the ‘Sustainably Unlocking the Economic Potential of Lake Turkana’ programme inception phase. A follow-up workshop will take place in Turkana County from March 25 to 28, with stakeholders from that side of Lake Turkana.

By Jim Woodhill, Foresight4Food Initiative Lead

Last month (November 2023) I had the wonderful experience of engaging with over fifty young leaders from across Africa, joined by colleagues from Bangladesh, Nepal, and Jordan. We had all gathered in Naivasha, Kenya, to explore how skills in facilitating foresight can be used to help bring about food systems transformation.

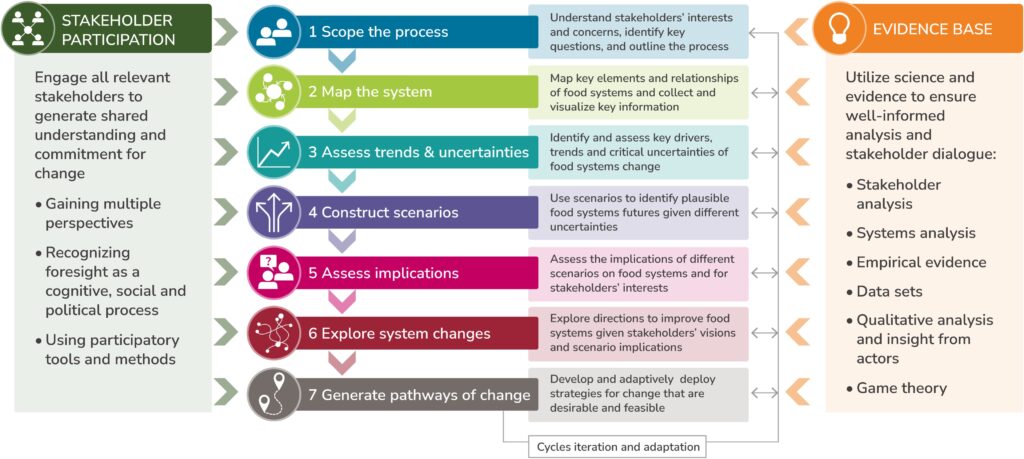

The fascinating work these young leaders are involved in and their deep interest in understanding how to be more effective change-makers was truly inspiring. It was encouraging to see how valuable they found the foresight for the food systems change framework and the associated set of participatory tools for engaging stakeholders.

Participants all came with projects from their own countries where they are keen to use foresight and systems thinking to help facilitate change in food systems by bringing together different stakeholders. The participants were from diverse backgrounds representing policy, the private sector, NGOs, and academia.

A Guiding Framework: During the workshop we introduced participants to an overall guiding framework for facilitating foresight for food systems change. A range of participatory tools were used for systems analysis, development of future scenarios and exploring systemic interventions. To bring reality into the workshop, the Kenya horticulture sector was used as a case study for the foresight analysis. Participants spent a day visiting horticulture farms, packing and processing facilities and the local market. They explored with local stakeholders how they saw the future for the horticulture sector and the issues that “keep them awake at night”.

Visualising the system: The workshop was highly interactive with participants practicing in the facilitation of a range of participatory tools which can be used to bring stakeholders into dialogue around systems change. One of my favourite participatory tools “rich picturing”, which enables a diverse group of stakeholders to develop a shared understanding of a system by drawing it, was found by participants to be especially powerful.

Data-driven dialogue: To go deeper into the systems analysis it is valuable for stakeholders to explore the available data on key drivers and trends. Over 100 graphs visualizing key data points related to the Kenya horticulture sector and food systems at national, continental, and global scales were collated and posted around the walls. The participants then explored this data in groups of three and discussed its implications and how it perhaps challenged their existing assumptions.

Exploring the future using scenarios: Central to the foresight approach is developing a range of different plausible future scenarios (generally with a 10 to 30-year horizon) for how the system might evolve given critical uncertainties. Workshop participants did this for the horticulture sector, looking at factors such as how diets might change in the future, regional and global trading relations, severity of climate change, and the enabling policy environment for small-scale producers and the small- and medium-scale enterprises (SME) sector. The scenarios help to identify future risks and opportunities for different stakeholder groups and society at large. They also help to unlock creative thinking about how to “nudge” systems towards more desirable futures and away from less desirable ones.

The deeper issues of systems change: It is easy to talk about systems change. In reality trying to change systems bumps into all the difficult issues of vested interests, power relations, ideologies, and deeply held cultural beliefs. On top of this human and natural systems are complex and adaptive and behave in self-organising, dynamic, and often unpredictable ways. It doesn’t mean you can’t intervene to try and bring positive change. But it does mean that top-down, linear, and mechanistic models of change generally don’t work. The workshop engaged participants in deep and challenging discussions about what it means to be a leader of systems change. This included the need to be adaptive, how to create alliances for disrupting existing power relations, the importance of building relations between diverse stakeholders, and the importance of patience. Systems change often requires taking time to build the foundations for change without being able to know when circumstances might suddenly unlock opportunities for big steps forward.

Identifying directions for change and intervention options: Developing directions and pathways for systems change is the most difficult and challenging part of the foresight for systems change process. It is highly context-specific and requires a deep insight into the political economy of the situation. Cause and effect mapping, theory of change thinking, and causal loop analysis can all help in identifying opportunities for intervening which could help to drive systems change in desired directions. Bringing change will often require an integrated approach to technological, institutional and political innovation. During the workshop causal loop diagrams were used to explore possible entry points for shifting horticulture systems in ways that could improve health, livelihoods and the environment.

New friends, new networks and big ambitions: After an intense week of learning and sharing participants left inspired to apply the foresight approach back in their own work environment. New friends were made and there were clear calls to find mechanisms to support ongoing networking and peer support.

Many thanks to the facilitation and support team who made a fantastic week possible, Gosia McFarlane, Marie Parramon-Gurney, Kristin Muthui, Bram Peters, Joost Guijt, Riti Herman Mostert, and Abdulrazak Ibrahim. The event was made possible by support from the Mastercard Foundation.

More information about the Foresight4Food Framework of Foresight for Food Systems Change can be found on our website, and an updated approach paper will be published in January 2024.

By Amina Maharjan

Achieving the Sustainable Development Goals by 2030 is becoming ever more challenging in the Hindu Kush Himalaya (HKH), as the region grapples with the many complex and interconnected crises of climate change, biodiversity loss, food and water insecurity, and growing economic inequality, among others. We do not need a crystal ball to help us see what the future climate could hold in store for the people and environment of this region. It is already experiencing the devastating impacts of climate change, with new temperature and precipitation records continually being surpassed. More severe and frequent extreme weather events, such as droughts, floods, and avalanches are becoming the norm. For the HKH, elevation-dependent heating means that even a temperature increase of 1.5°C is too hot for the sustainable wellbeing of the region’s people and ecosystems.

If ‘business as usual’ and current emission trends continue, the HKH is on course to experience irreversible changes in its natural and social systems. Without enough food, water, or energy, life would be challenging for the millions of people who call the HKH home, and for some, it would simply be unliveable. It is vital that we start thinking about what kind of future we want to create and how we can act when the worst-case scenario thresholds are crossed. We need to plan for an uncertain future and be better prepared for these worst-case scenarios.

In order to brainstorm together on these shared uncertainties, over 40 participants representing 25 organizations from six countries in the region – Bangladesh, Bhutan, China, India, Nepal, and Pakistan – and beyond – Austria, Thailand, United Kingdom, United States of America – came together for a consultative workshop on ‘Foresight and Scenario Development for Anticipatory Adaptation in the Hindu Kush Himalaya’ on 19–20 September 2023, organized by the International Centre for Integrated Mountain Development (ICIMOD) in Kathmandu, Nepal. The participants included representatives from governments, international organizations, NGOs, think tanks, universities, and research institutions.

Over the two days, the participants engaged in a horizontal scanning exercise to look at potential changes/disruptors in the HKH region in the future. The group also looked at building capacity for foresight and futures thinking at different scales of planning – from national to local levels.

Foresight and scenarios are tools that can help us reimagine plural futures. They help us think about the future in systematic, rigorous, and inclusive ways. It involves identifying potential future trends and challenges in order to develop strategies to address them. This approach has not been used widely in this region, but that needs to change as we prepare for an uncertain future.

This gathering was the beginning of a process to encourage futures thinking in the region. Overall, there was consensus on the need for futures thinking across sectors and scales and a commitment to continue collaboration. As a participant from Bangladesh highlighted “We cannot only depend on the past (and historic trends) to plan our future under the rapid change and uncertainty that we are witnessing in the region. It is critically important to envision futures at different scales and with diverse stakeholders to drive our actions now.” Without foresight and scenarios thinking, no organisation or community can remain future fit.

Such planning is especially crucial for a region as vulnerable as the HKH – subject not only to the extremities of its geography and topography, but also because of its varied social, demographic, political and economic conditions. Just one major weather event can set communities back 20 years in development. We must think creatively and long-term about how to address the major challenges, and we must do it now.

by Bram Peters

The UN Food System Summit +2 StockTakingMoment is behind us. It was attended by more than 155 National Food Systems Convenors were in place and 107 countries shared their national food system transformation pathways accounts. 3300 participants, including delegations from 182 countries, 21 world leaders, and 126 ministers (particularly from the Global South) joined.

What highlights and insights remain from the 3-day event in Rome? Joining on behalf of Foresight4Food, I felt it was a mixed bag, with both positives and negatives. Below are some insights, facts, backdrop, and other observations:

First off, a few facts were shared which really hit home:

According to Amina Mohammed, Deputy Secretary General of the UN, we are in the worst possible shape to reach the SDGs. Almost all indicators are lagging behind.

- 2.4 billion people across the globe, mostly women and people in rural areas, did not have consistent access to nutritious, safe, and sufficient food in 2022 (according to the latest SOFI report 2023).

- The world is not on track to reach the SDGs: only 15% of the 140 targets are on track since the 2015 baseline. Close to half of the targets are moderately or severely off-track.

- To achieve the Zero Hunger goal by 2030, IFAD stated that an additional $400 billion investment, per year in food systems is required, meaning efforts must be doubled in half the time. For reference: not doing anything would cost $12 trillion.

- It is projected that, by 2050, 70% of people will live in cities. At the same time, in those areas, consumption of processed and convenience food is increasing, with impacts on obesity, diabetes and other non-communicable diseases.

Some geopolitical and climate change-related dynamics in the backdrop:

- Southern Europe has experienced a heatwave of unprecedented levels, with high temperatures and wildfires from Rhodes to Spain. In Rome, temperatures have peaked at 41.8 degrees Celsius in recent weeks.

- The Russia-Ukraine war and Russia’s intention to withdraw from the Black Sea Grain Deal (BSGD) and a forum with African leaders was to be held in Saint-Petersburg after the summit. According to IFPRI, under the BSGI, about “65% of wheat was exported to developing countries. This includes 725,167 tons of wheat exported through the World Food Programme to help relieve hunger in Afghanistan, Djibouti, Ethiopia, Kenya, Somalia, Sudan, and Yemen. By contrast, about 83% of maize exports under the BSGI have gone to developed countries and China” (IFPRI, July 2023). This comes in the wake of a report that indicated that majority of the Black Sea Grain Deal production was consumed in Europe and used for animal feed.

- Italian host, Prime Minister Meloni, opened the summit, referencing the positive nutritional aspects of the ‘Mediterranean’ diet, but also had just a week earlier co-led the signing of a controversial migration pact between the EU and Tunisia. This was alluded to in her welcoming speech, where she urged for further investment especially in Africa so that jobs are created on the continent and sought in Europe.

- Ethiopian Prime Minister Abiy Ahmed was one of the speakers at the Opening Ceremony. Ethiopia and her northern neighbours are still negotiating on the planned dam along the Nile, which would directly affect food systems in Egypt and Sudan—no mention of cross-border resource sharing in his remarks.

Key takeaways:

- Food systems knowledge has deepened and capacities on food systems approaches have generally grown. This includes how countries use this but also the application within various Rome-based agencies. Now it will need to be seen whether coordination on such a diverse range of issues can improve and whether implementation increases pace. A hint of this integration was seen in the fact that clear links are made to the upcoming SDG conference and the COP28.

- Urgency is recognized as high, which made it very relevant to hold this UNFSS+2 StockTake to maintain momentum. Having a visible and active participation of high-level political representatives showed widespread commitment. However, the lack of substantial presence from Northern countries with commitments to their own national transformations was a missed opportunity.

- ‘Transformation’ was spoken about often, but the sense of real transformation ongoing is not apparent yet. A few insightful examples: the discussion on true pricing of food, a study in Andhra-Pradesh where agro-ecological farm production empirically demonstrated equal economic earning and better social and environmental benefits compared to conventional farming approaches; and the example by Switzerland on the establishment of a citizens’ assembly to offer recommendations for Switzerland’s food policy to break their parliamentary deadlock surrounding agricultural policy (something the Netherlands can learn from?).

- A side event about livestock was interesting with debate about the contribution that the sector has regarding GHG emissions, livelihoods, nutritious food, and what was being done in different parts of the globe.

- It was heartening to hear the enthusiasm in the stories of the national convenors, the driving forces for coordination and collaboration at national levels. However, it was also seen that many countries do not yet have strong institutional mechanisms in place to support cross-sectoral decision-making.

- A lot of important topics were addressed, including multi-stakeholder collaboration; inclusion; school meals; food security in (poly)crises; budgeting and financing for national Action Plans; policy alignment across sectors; and climate resilience. Multiple leaders from South America and EU mentioned agro-ecology. Some topics I missed included tackling unfair international trade agreements and improving global food trade governance (as referenced here in a (Dutch) long read by colleague Bart de Steenhuijsen Piters from WUR).

- Foresight approaches appeared highly relevant, as stakeholders shared the need to scan horizons for upcoming trends; build resilience for anticipatory approaches (WFP shared an example from Niger where less food aid was needed due to improved resilience approaches); and include ‘lived’ (indigenous) interpretations of past and future- alongside scientific evidence- in our transition pathways.

- Accountability did not receive much attention. With the exception of special events on the first day of the UNFSS on measuring and bench-marking, there was relatively little accountability of progress toward promises made at the 2021 Summit. It will be very important, at a next StockTake, to get more metrics and data of countries on their national transformation pathways progress.

Other observations:

- The UN agencies were pleased to see the high-level turnout, especially from the South. Private sector, youth, and indigenous groups were represented in smaller numbers but made active contributions.

- Engagement from member countries, the private sector, civil society as well as the scientific community seemed less than before.

- Limited (or less visible?) participation of Europe and the USA. Whether this is a sign of decreased interest, or because there were fewer planned preparations for UNFSS+2 compared to UNFSS, is yet to be seen.

- (only) A few countries from the global North reported on their own food systems pathways and challenges instead of reporting on their ODA-funded food system support to partners in the global South.

- A counter-summit was organised, raising issues of lack of inclusion and corporate-led influence.

- Quite a few UN Agencies are investing and learning about foresight. For example, the Future of Food and Agriculture publication (FOFA DDT) was presented at a side event. Also, the newly reinvigorated FAO Office of Innovation is actively interested in foresight methods and eager to exchange with Foresight4Food.

- A nice photo exhibition was held in the main atrium, called ‘Food Futures’, funded by the European Commission Joint Research Centre, with the objective to explain food systems and realising that cultural shifts are needed to transform these.

Side-event on multi-stakeholder collaboration

At the Stock Take Moment, Foresight4Food was able to contribute to a side event called ‘Multi-stakeholder collaboration for food systems transformation: From concepts to Action ‘. This side event (see here the recording), organised together with UNDP, UNEP, FAO, Global Alliance for Improved Nutrition (GAIN) and Netherlands Food Partnership focused on the need to bring people together to bring change. How to ensure inclusion, tackle power differences, and create a shared language to help with the national pathways? There is such a diversity of food system stakeholders. In a diverse panel with representatives from Vietnam, South Sudan, Nigeria, Switzerland, and Kenya, the question asked was: ‘How’ do we do a multi-stakeholder collaboration?

Key experiences shared included how the Vietnamese government went down to the local level to collect insights, conveners who actively consulted the grassroots level in South Sudan, iterative rounds of consultations at different levels and regions in Nigeria, and how a citizen’s assembly was established in Switzerland to advise on food systems.

Wangeci Gitata-Kiriga, representing Foresight4Food Initiative, shared how in Kenya, Foresight4Food combines a participatory process with an evidence-based understanding of the current food system and the possible future of the food system. Using participatory visual approaches such as Rich Picturing, stakeholders exchange perspectives, talk openly about power, and start developing a shared language on uncertainties and possible futures of the food system.

The session concluded with the observation that we need to understand ‘transformation’ better, that this requires a huge effort, and needs inclusiveness and diversity. We have a broad range of tools at our disposal that we can use. It is also not about the powerful vs the powerless, but rather also about breaking barriers, creating and maintaining an equal playing field, and involving the unexpected and unusual players.

See the website NFP Connects of the Netherlands Food Partnership for a more detailed summary.

By Zoë Barois

To support the lasting and valuable development of any multi-stakeholder network, it is important to explore its perceived values and positioning from the perspective of various key and transdisciplinary stakeholders. In line with this concept, five members from the Advanced Masters International Development (AMID) Programme at Radboud University including Emma John, Guusje Dijkstra, Meg van Grinsven, Nadia Rinaldi, and Zoë Barois, collaborated to explore stakeholder perceptions on the perceived values of the Foresight4Food Initiative and the risks it faces when participating in multi-stakeholder networks.

The team conducted seven interviews with foresight experts and practitioners from private, governmental, research, and multilateral organizations, in addition to experts in multi-stakeholder partnerships. Some interesting findings came up in the interviews that led to the development of several guidelines.

Perceived Values of Foresight4Food

The interview participants appreciated that the Foresight4Food Initiative connects stakeholders to (new) players in the field and enables their work to be critically examined by specialists. Being able to harness expertise in the field of foresight and apply this to food system transformation was highlighted to facilitate a deeper understanding of the suitability of foresight tools in diverse contexts.

Additionally, the interviewees highlighted Foresight4Food’s unique value is that it is one of the few initiatives working on food system transformation on a global level, as opposed to most initiatives that focus on national or regional scopes.

Foresight4Food’s deliberate focus on the processes (rather than the product) of forecasting future scenarios was emphasized as a value in itself as it is a strategic tool for food systems transformation.

An interviewee highlighted the benefit of Foresight4Food’s open-access resource platform and their ability to provide a neutral meeting space that facilitates cross-learning and a deeper understanding of foresight and food system trends among stakeholders.

“…we see it [Foresight4Food] as a great forum to exchange learning, for example, we just took the exploratory scenario planning process and customized it for use with multi-stakeholder partnerships… this is a tool that already existed that we kind of adapted and would love to share how that works so other people can pick that up…’’ – Foresight Practitioner

Risks Faced by Foresight4Food: Positionality & Durability

During the multi-stakeholder interviews, several thematic risks emerged relating to Foresight4Food’s durability and positionality within the active foresight landscape.

The long-term thinking required to envision the outcomes of Foresight4Food poses challenges in terms of sustainability as this makes it difficult for organizations to invest in the initiative due to investors’ often short-term vision and the need to “show results as quickly as possible” – Foresight Expert — a common challenge faced by many organizations in the development sector.

In relation to Foresight4Food’s positionality, the initiative faces the risk of being duplicated by similar organizations and, consequently, being “squeezed out by the big players if they feel that we are an irritant on the side of what they consider to be their patch” – Foresight Expert

Lastly, Foresight4Food faces the risk of not being “democratised enough and sublevel enough” to truly get involved with the root causes of the food system issues. This stems from the current engagement of true experts in the field and thus emerges as an ‘’elite network’’ initiated by two high-profile universities. This lack of inclusivity is further emphasized by interviewees “not capable of being inclusive we are going to fail giving to those that actually can benefit the most from our work” – Foresight expert

Subsequently, one of the main challenges of F4F is effective outreach and engagement with stakeholders.

Proposed Guidelines

Taking into account Foresight4Food’s vision and the thematic risks which emerged from the multi-stakeholder interviews, several guidelines were generated aiming to support the sustainable and valuable development of Foresight4Food’s multi-stakeholder network.

1. Foresight4Food’s Positionality

Enhancing F4F’s positionality is crucial for the initiative to find its niche. Therefore, the following guidelines are suggested:

- Conducting a needs assessment of the current network members can enable F4F to identify and prioritize their needs.

- The outcomes from the needs assessment can provide an informed direction to perform a visioning exercise. Matchmaking between desired visions and the long-term forecast

- Continuously update the existing mapping of foresight initiatives across the food system. This can be used to perform a competitor analysis to assess the existing gaps in the foresight and food systems field and formulate associated research questions.

- Facilitating smaller partnerships amongst F4Fs members, was highly valued by an interviewee thus F4F could link initiatives conducting complementary activities identified in their foresight initiative mapping, further enhancing their value.

2. Sustainability: Foresight for Foresight4Food

To ensure Foresight4Food’s sustainability and longevity, Foresight4Food must become more attractive to investors:

- ‘Foresight for Foresight4Food’: generating potential future scenarios for F4F to clarify what outcomes and impact F4F envisions in its short- and mid-term futures.

- This can be further enhanced and formulated into concrete goals by a Monitoring, Evaluation & Learning (MEL) expert, who can contextualize F4F’s Theory of Change towards each of the five FoSTr countries, providing concrete outcomes, which are actualized for funders to grasp and support.

- Develop a funding strategy to generate a diversified funding portfolio to ensure financial flow from a variety of sources.

- Attract funding from the private sector and from philanthropy as they are harboring the most financial power within the field.

- Consider transferring core operations and leadership to stakeholders in target operational areas (i.e., the FoSTr countries). This would require creating an inclusive roadmap for phasing-out and phasing-in new or alternative network partners.

3. Inclusivity & representativeness

To make F4F more inclusive, the following recommendations are provided:

- Stakeholder Characteristics and Roles Matrix to map to identify stakeholders who are not yet on board or have a low influence within the network.

- Introduce a ‘second circle’ around the steering committee to include a diversified set of stakeholders in the decision-making processes. This second circle could include farmers, youth representatives, and/ or representatives from the five FoSTr programme focus countries.

- Generate a sense of ownership amongst second circle members through co-creation

To conclude

Foresight4Food Initiative is striving to develop and strengthen its network among foresight practitioners and different stakeholders. However, it gets challenging for any organization to work in a multi-stakeholder environment. Therefore, an exploratory look at the perceived values and positionality becomes imperative.

Foresight4Food, under its FoSTr programme is working in five countries across Africa, Asia, and the Middle East, conducting foresight orientation, stocktaking, capacity building, and exploring ways to transform the country’s food systems. Thus, making it the right time to explore sustainable positioning from a stakeholder’s perspective.

Reflections on the Third Global Foresight4Food Workshop in Montpellier 2023

By Bram Peters, Food Systems Programme Facilitator

Strike? What strike?

Amid the turbulence created by strikes in France, a diverse and committed group of people still managed to get to and from the Third Global Foresight4Food Workshop in Montpellier from 7-9 March.

Perhaps, as foresight practitioners, we should have seen it coming! You would think that foresight practitioners who make it their business to look into the future might be better at anticipating turbulence, or at least a substantial level of social upheaval.

Why go through the trouble to come anyway? Because food systems are in turbulence as well. Never has there been a more urgent need to transform food systems. More than 3.1 billion people globally do not have access to healthy diets. The impact of climate change in the form of droughts and disasters is increasing. Agri-food systems are responsible for one-third of greenhouse gas emissions. The Covid-19 pandemic and the Russia war in Ukraine have shown how integrated, yet fragile, the global food system is.

We need foresight in food systems transformation

Yet, “the greatest danger in times of turbulence is not the turbulence; it is to act with yesterday’s logic” (according to futurist Peter Drucker). That’s where foresight comes in.

We need a long-term perspective to explore alternative pathways to reach desirable or avoid undesirable food system changes.

Following from the UN Food Systems Summit in 2021, many countries are searching for ways to navigate change and develop anticipatory policy to guide them.

As such, the issue on the table was: how can the foresight community of practice offer support and relevant advice to food system stakeholders?

Creating a safe space to think, connect and engage

In Montpellier, Foresight4Food brought together a diverse group of foresight practitioners, researchers, users of foresight and implementors of food systems approaches to discuss how foresight can contribute to national level food systems transformation pathways amid all this turbulence.

The Masterclass on the 7th generated a lot of energy, a shared language, and many practical explorations of tools and methods. The main Workshop on the 8th and 9th saw interactive exchanges, presentations of valuable projects and sharing of insights.

Among others, organisations such as FAO, CGIAR, GFAR and CIRAD shared ground-breaking applications of foresight thinking linked to food systems. There were cases from Asia, Africa; thematic cases on food systems data; new and past initiatives; dashboards and multi-stakeholder processes.

Researchers and data experts, such as from Wageningen University and Food and Land Use Coalition, shared innovative tools and models to advance new ways of projecting trends.

Critical perspectives were shared. Insights were brought from Africa and Asia, such as by Forum for Agricultural Research in Africa, and much more.

Moving the needle: developing our forward agenda

We, as Foresight4Food team, gained a lot of energy and motivation to continue fostering this vibrant network.

A few pickings of things we want explore moving forward. Develop and encourage ‘Communities of Practices’ through active partnership principles. Make a meta-analysis of existing food system foresight cases and comparative insights and lessons. Create guidance for foresight community on the process of actually doing foresight for food systems. Develop key principles for quality approaches and a toolbox to support implementation.

Thankfully, even in the face of the French strikes, a quality characteristic among foresight practitioners is the ability to be adaptable and flexible – as is needed when you work with the complexity of food systems.