Preparations are well underway for the 5th Global Foresight4Food Workshop set to take place in Amman, Jordan, from 15 to 19 June 2025. This dynamic event will bring together foresight thought leaders, innovators, and changemakers from around the world. Designed to spark dialogue, ignite creativity, and drive tangible progress, the workshop offers a unique platform to advance the global foresight agenda for food systems.

In the lead-up to the event, Asem Nabulsi —Foresight4Food FoSTr Programme Deputy Facilitator in Jordan—shares his perspectives on the critical challenges and emerging opportunities shaping global food systems. In this blog, he offers valuable insights into the urgent need for systemic change and highlights the powerful role foresight can play in building a more equitable, nutritious, and sustainable future.

Beyond the Macro Lens: Reclaiming the Food System Narrative

A critical concern shared by many in the global food space is that the decisions influencing food systems are often made at the macro level, detached from the lived realities of communities and the interconnected outcomes they produce. The fragmented approach overlooks how policies and practices affect health, nutrition, livelihoods, and the environment. Foresight provides the structure to consider these dimensions together, helping stakeholders envision multiple futures and make informed, holistic decisions.

Sharing Real-world Experiences

The success of the upcoming Foresight4Food Global Workshop hinges on more than dialogue—it depends on active participation, sharing real-world experiences, and co-creating concrete, implementable recommendations.

When foresight thought leaders, innovators, and food system stakeholders from around the world sit together, it should not just be about knowledge exchange; it should be about laying the groundwork for lasting change through mutual understanding and collective action.

From Dialogue to Action: Integrating Insights into Practice

I see this global workshop as a springboard to rethink professional strategies. One needs to fully understand the importance of multistakeholder perspectives and collaborative design of actions that consider the full spectrum of affected groups. This approach ensures that decisions are not only visionary but grounded in equity and practicality.

Regional Collaboration: The Untapped Potential

While food systems are often discussed within national borders, I would like to remind you that no country exists in a vacuum. Regional interdependence, from raw materials to trade and market access, necessitates greater collaboration. To build more resilient food systems, I suggest enhancing bilateral and multilateral trade, establishing regional food hubs, diversifying trade routes, and creating supportive regulatory frameworks. These steps could buffer regions against future disruptions and strengthen food sovereignty.

The Leadership Imperative

Leadership is essential for steering transformation. Setting a suitable regulatory environment, mapping the current food system and agreeing on the goals and best way forward to reach the desired goals, fostering a cooperative environment for change, uniting stakeholders understanding and action towards the desired goals, taking the decisions and actions that incentivise actions that enhance positive food system transformation at the different levels and for different stakeholders, raising awareness for all actors affecting and being affected by food systems, creating a national re-iterative process to regularly examine the efficacy of changes made and looking out for changing factors that might affect the food system, and starting the communication and actual practical steps for regional cooperation.

From Vision to Implementation: Making Collaboration Stick

A practical roadmap to ensure the workshop leads to a lasting impact is to focus on the importance of moving from vision to implementation. It means building a shared understanding, defining common goals, and designing actions that are informed by the perspectives of diverse stakeholders across multiple levels. Open discussions around potential trade-offs and strategies to mitigate negative impacts are also key. To translate dialogue into action, I would highlight the need for clear, well-defined plans with assigned responsibilities and timelines. I believe that this structured yet adaptable approach is crucial for fostering durable cross-sector collaboration and meaningful progress.

With these reflections in mind, I look forward to welcoming you in Jordan and seizing this unique opportunity to catalyse both regional and global efforts toward meaningful food system transformation.

By Bart de Steenhuijsen Piters

Foresight4Food is organizing its 5th Global Workshop in June titled “Foresight for Transformative Action in Food System”. To raise the tip of the curtain on this exciting event, we have asked Bart de Steenhuijsen Piters, Senior Scientist Food System at the Wageningen University and Research and Foresight4Food FoSTr programme facilitator, to share some of his thoughts and expectations. Here is what he has to say:

The myth of the “Global” food system

As we approach the 5th Global Foresight4Food Workshop in Jordan, I find myself reflecting on what it truly means to transform our food systems—and what role foresight can play in helping us get there.

Let me begin with a provocation: I believe the idea of a global food system is, in many ways, an illusion.

When we speak about the global food system, we often forget that it’s simply the aggregation of countless national and subnational systems. No one actor is responsible or able to govern it. The UN may think so, but that is an illusion. Instead, we have trillions of individuals, institutions, and businesses shaping the system every day. This diffused responsibility makes governance incredibly complex and leads to a kind of mystification, where the real (geo)political and economic dynamics at lower levels are ignored or misunderstood. Yet, all these food systems are connected for sure. Just look at the effect of the Trump administration and its tariff policies on food markets worldwide.

This is precisely where foresight can help—not by giving us a top-down blueprint but by helping us navigate complexity, anticipate challenges, and co-create transformative pathways.

What success looks like for the 5th Global Foresight4Food Workshop

For me, success for the 5th Foresight4Food Workshop doesn’t lie in just producing new scenarios. It lies in helping us figure out how to act in those scenarios.

I want us to co-develop a joint narrative around food system transformation. I want us to compare how different countries are exploring their options. Most importantly, I want us to dive into the real-world, practical question: how do we move from insight to impact? How do we build pathways for change that involve multiple actors, each taking responsibility? And how do we lead, especially when the pathway forward is contested and uncertain?

These are the questions I hope we will tackle together in Jordan.

Regional collaboration is crucial

One of the most powerful levers for transformation is regional cooperation. Not only does it allow us to share experiences and foresight approaches among practitioners, but it also aligns with the need for more localized, resilient food systems. This is especially critical in times when global markets are being challenged, multinational food companies continue to concentrate their power and food is more and more used for geopolitical purposes.

We need shorter, regional supply chains and production systems that are better tailored to local contexts. Regional platforms are essential for this. They help us valorise knowledge and foster innovation where it matters most—on the ground.

The leadership we need

Food system transformation demands leadership on many fronts.

We need business leaders who are willing to shift course—who can rethink business models that currently drive unsustainable outcomes and align their strategies with public goals like healthy diets and environmental sustainability.

But we also need leadership that can manage conflict and mediate between diverse interests. Sometimes, this means making bold policy decisions, even when powerful actors resist change. That kind of leadership isn’t easy—but it’s necessary.

A call for courage and collaboration

My hope for this workshop is that it becomes a space of real collaboration. A space where participants listen to each other, share not only their successes but also their failures, and resist the urge to simply push their own agendas.

We need the courage to explore the unknown together. To ask hard questions. To face the uncomfortable truths. Because only then can we unlock the systemic changes our societies so urgently need—and that, too often, are still moving too slowly or stalling altogether.

I look forward to learning with and from all of you in Jordan.

By Bram Peters

The future of food systems is uncertain, yet one thing is clear—transformative change is urgently needed. Climate change, inequality, and geopolitical instability are reshaping how food is produced, distributed, and consumed. How can we navigate these complexities and create a more sustainable, resilient food system?

At the Power of Foresight Workshop held on 30-31 January 2025 at the FAO headquarters in Rome, experts and practitioners gathered to discuss how foresight can drive food systems transformation. Their insights reveal a crucial truth: the process itself— working with complexity, embracing inclusivity, diverse perspectives, and collective intelligence—is central to making real progress.

Insights from the ‘Power of Foresight’ Workshop

- 17 different cases and the stories of 48 participants from 27 countries demonstrated that foresight approaches have much to offer to the process of food systems transformation

- Working with complex systems is what it’s about, and effective foresight practices for food systems change to embrace this

- Openness to new and inclusive perspectives should be central to all foresight for food systems transformation efforts

- The process brings the answer – and foresight can bring awareness of crucial process elements such as collective intelligence, agency, time and scale

- Embracing the ‘ifs’: how you do foresight, and what comes before and after, is just as important as the development of scenarios

- Foresight is not one approach or one methodology – there are a diversity of ways to go about it

- The national food systems pathways can benefit from foresight approaches

Photos: 30 January 2025, Foresight4Food workshop. FAO Headquarters, Rome. Photo credit: ©️FAO/Cristiano Minichiello

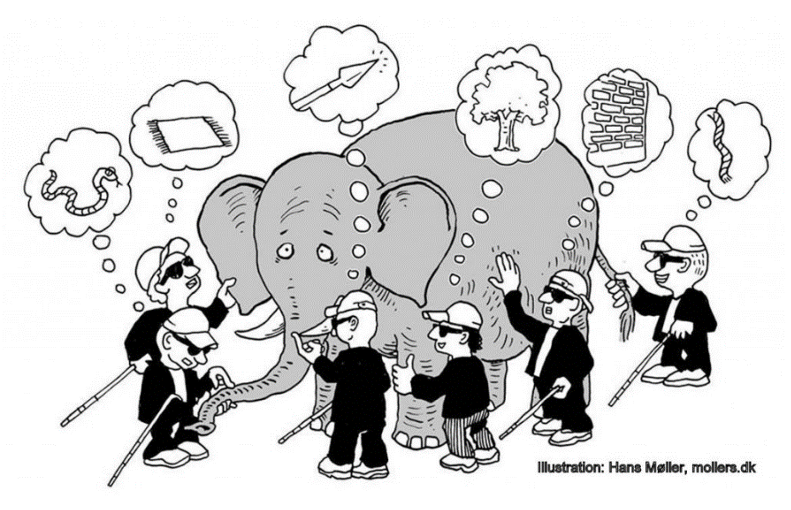

Working with complex systems: Let’s talk about the elephants in the room

When it comes to food systems transformation, there isn’t just one elephant in the room—there are many. These metaphorical elephants represent the complex, interconnected challenges we face, and ignoring them only hinders progress.

- First, as a whole range of interrelated challenges and assumptions we are not working on enough: whether that’s climate change, human rights, global geopolitical turbulence, growing inequality. All these challenges together form a context of global polycrisis.

- Second, we can see elephants in the room related to our apparent inability to take decisive transformative action in food systems: a lot of talk, limited action.

- Finally, we can see elephants as representing systems. An elephant can represent a dynamic, complex food system, of which we might only be able to see or understand the trunk, tusks, ears or tail.

Like the elephant and the blind men metaphor (see image to the right), food systems are deeply interconnected with global issues like climate change, inequality, and geopolitical instability. Tackling these requires a holistic approach, recognizing that transformation cannot happen in silos.

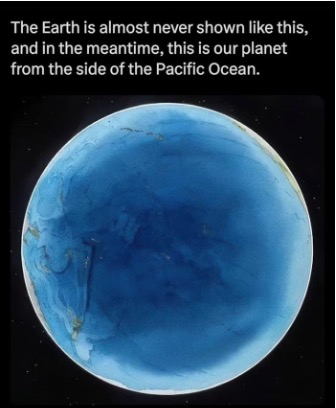

Gather new and inclusive perspectives – and change your own

What’s central to talking about complex food systems is perspective. We all have different mental images of food systems—whether local agriculture, marine ecosystems, or trade networks. Expanding our perspectives helps identify new entry points for addressing issues like malnutrition, poverty, and sustainability.

For some, like from the Pacific region, it’s about marine ecosystems in which food is central. Changing your perspective can be a helpful way of looking at a complex topic: such as to see the Pacific food system composed not of ‘small island states’ but rather ‘large ocean states’ connected with the global food system through trade, governance, and oceanic currents. Why is flipping your perspective so important? It helps to reframe entry points for discussion with other stakeholders and view the root causes of things like malnutrition, non-communicable diseases, poverty and human rights abuse in food systems differently.

If you are able to change your perspective, it helps to understand the viewpoints of those less heard. Having an inclusive process to gather different viewpoints is crucial to changing perspectives and behaviour, mobilising for collective action and creating shared visions of the future.

The process is the answer

Ever tried herding cats? Well, transforming food systems is about fostering C.A.T.S.—a process centred on:

- Collective intelligence – Multi-stakeholder collaboration and co-creation

- Agency – Empowering change through action

- Time – Bridging past, present, and future

- Scale – Recognizing interconnections between local and global systems

So, what does it mean to herd cats when talking about food systems? It means there are no magic bullets: the process is central to the outcome.

Effort on addressing the ‘ifs’

Foresight can be of great added value to support the food systems transformation process. Whether it is about co-creating alternative futures, conducting backcasting towards a more desirable scenario, highlighting the cost of delayed action, or informing anticipatory policy – foresight and scenario tools are a key toolbox in the hands of systems change champions.

In order for foresight to be effective, there are a number of conditional ‘ifs’ i.e., if foresight experts and facilitators:

- Are able to move beyond added value, tackling pre-conditions, obstacles, and constraints affecting how stakeholders prepare for the future.

- Not only preach to the converted – we need to involve stakeholders who think and act differently

- Are cognizant of power differences, lock-ins and political economy

- Build on other approaches that also provide value, such as design thinking, human-centred development and mission-oriented policy making.

- Pay attention to what comes before and after the development of scenarios

Scenarios only developed from the perspective of single organisations or without meaningful consultation and dialogue will not be effective.

Foresight approaches and national food systems pathways

There are a broad range of foresight approaches, some expert-driven or participatory, others quantitative, experiential, creative or analytical. Each has their value – but these needs come from a clear user need and scope within a food system. However, it is essential to keep in mind that foresight is a tool, not a panacea, and cannot address all questions.

With 156 national convenors driving progress through implementing 137 national food systems transformation pathways, the upcoming UNFSS+4 Stocktaking Moment (July, Addis Ababa) presents an opportunity to share lessons and strengthen impact. What we have seen the past two days in Rome, is the incredible richness and diversity of initiatives that use foresight to support the food systems transformation process.

Sharing the lessons from these initiatives, communicating the potential of foresight, and supporting the national convenors to further realise the impact on transforming food systems outcomes will be crucial in the run-up to the Stocktaking Moment.

By Herman Brouwer, WUR lead for FoSTr and Wangeci Gitata-Kiriga, FoSTr Country Facilitator Kenya

How can foresight transform the lives of pastoralists, fishers, and farmers in Marsabit County, Kenya? Marsabit County faces formidable challenges, with the escalating impacts of climate change threatening its food systems and livelihoods. Despite decades of significant support from development partners and government initiatives, the tangible results remain limited. This begs the critical question, inspired by David Peter Stroh: Why, despite our collective best efforts, have we struggled to foster lasting, positive change in Marsabit’s food systems?

Foresight could hold the key. By enabling stakeholders to anticipate future challenges, identify sustainable solutions, and adapt to evolving realities, foresight offers a transformative approach to addressing the county’s persistent issues. It’s time to rethink strategies and align efforts to create meaningful, long-term change for Marsabit’s pastoralists, fisherfolk, and farmers.

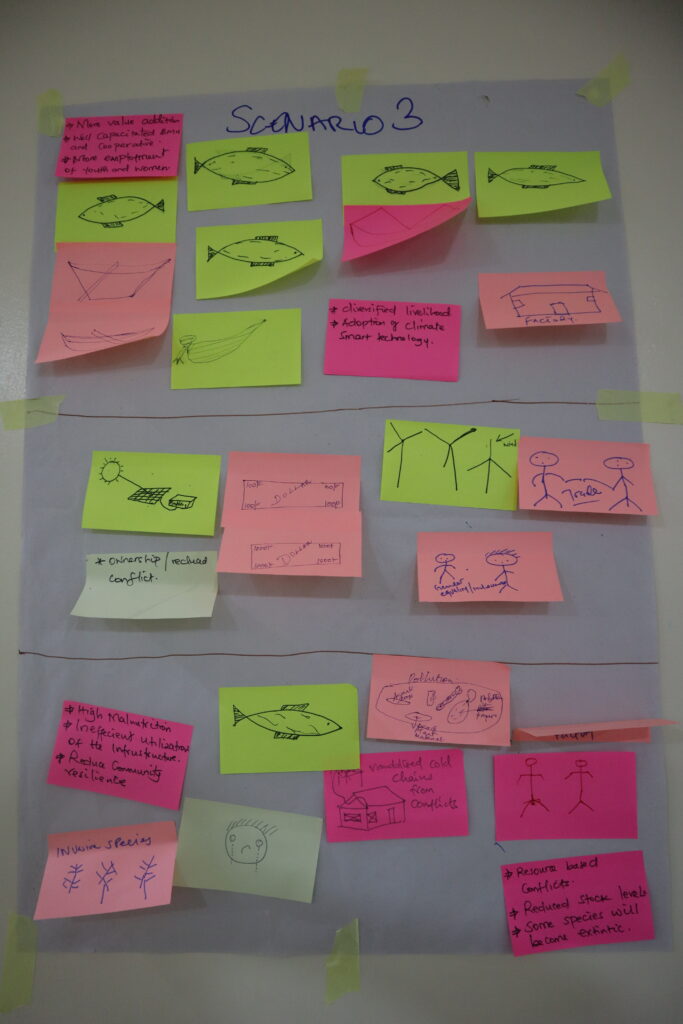

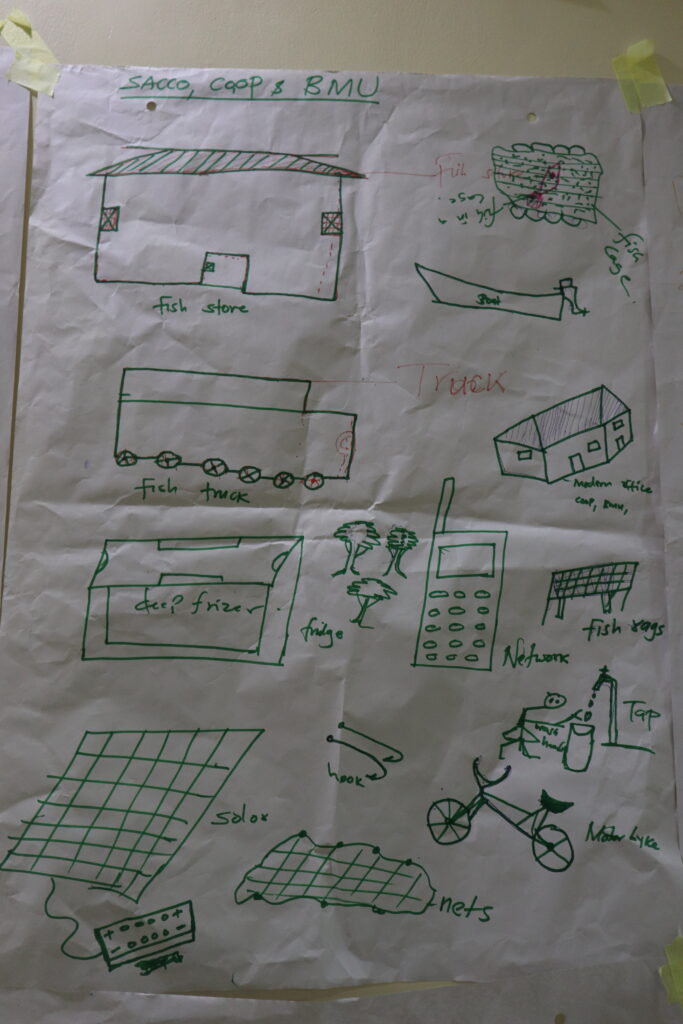

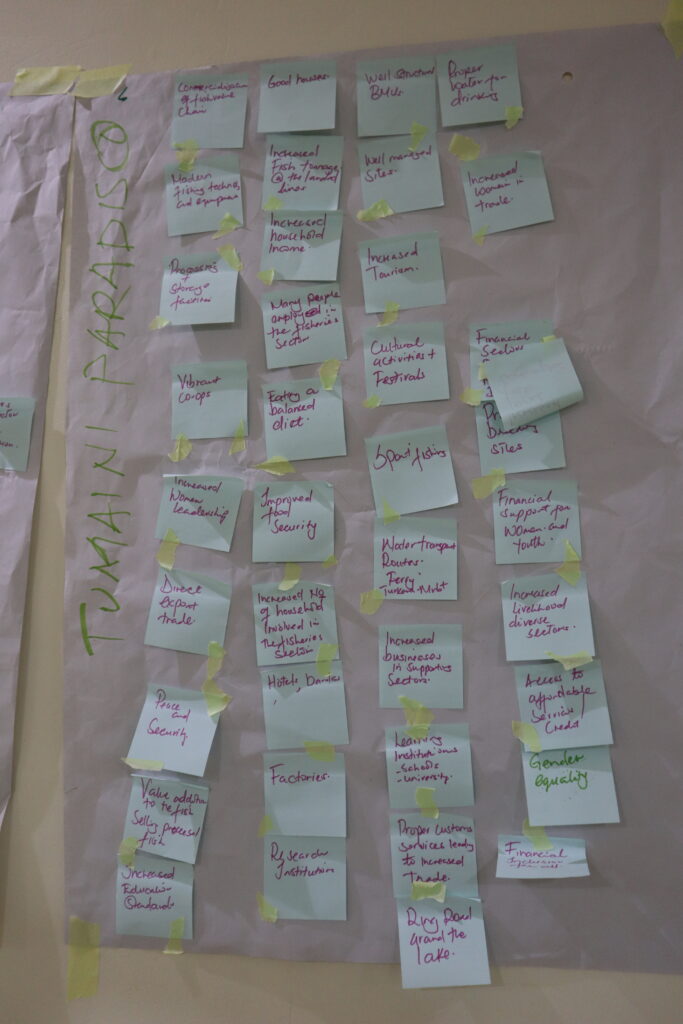

We brought stakeholders together in December 2024 to explore the above question, and to make a start to imagine different futures for the food system in Marsabit. Naturally, this involved a highly interactive discussion on the current food system and how we got to this situation – using a data walk with up-to-date data and analysis, as well as system maps. This provided the basis to jointly understand the dynamics of how food systems change (or resist change) and imagine how the food system could change even further in the next 10-15 years. The stories that participants came up with, based on their lived experiences in four distinct sub-counties of Marsabit, evolved into four scenarios. We used one of these scenarios (the ‘ideal one’ called Ajako, meaning ‘paradise’ in the Borana language) to create a vision for the future. We then identified the initial pathways and building blocks required to work towards this Ajako scenario.

Photo credit: Crispaus Onkoba/SID, used with permission

That’s the summary of where we ended up. However, an essential detail was omitted earlier: How do you ensure the right individuals and institutions are in the room? Achieving this required a carefully planned stakeholder engagement process, which began several weeks before the workshop. The process involved numerous meetings with individual stakeholders across the county to understand who was doing what, who was most invested, what had been successful, and what hadn’t worked in the past. The ultimate goal was to mobilize the most relevant and diverse stakeholders for the 3-day workshop.

We started by engaging the county leadership, relevant government departments, and development partners. But stakeholder mobilization didn’t stop there. We actively sought out voices often overlooked in food systems discussions: faith-based organizations, community groups, and private sector representatives.

Following the workshop, we ensured the initial excitement and momentum were sustained by maintaining contact with key participants. This effort culminated in the formation of a County Development Group, coordinated by the county government. This group brings together all actors actively engaged in food security initiatives, creating a collaborative platform for sustained impact.

Photo credit: Crispaus Onkoba/SID, used with permission

We argue that the investment in stakeholder engagement has been the most valuable ingredient of the foresight process so far. It has allowed our Kenya foresight team to obtain the right endorsements and buy-in at the right levels. Without getting the engagement process right, all participatory foresight tools, and supportive analytics, are at risk of falling flat.

There is a case to be made to only report on foresight processes after they are concluded, rather than at the start. This blog is an exception, to make the point that how you start matters.

The FoSTr Kenya foresight team, consisting of Results for Africa Initiative (RAI); Society for International Development (SID); International Livestock Research Institute (ILRI); University of Nairobi; Food and Land Use Coalition (FOLU); Wageningen University & Research (WUR); and the University of Oxford, will continue to support the County Development Group in Marsabit to coordinate actions of state and non-state actors towards achieving Ajako by 2040. A similar process is taking place in Nakuru County. Both have active linkages to Kenya’s national food system science-policy interfaces.

By Jim Woodhill – Lead Foresight4Food Initiative

It was great to participate in the next phase of Jordan’s journey toward food systems transformation as part of the Foresight4Food Initiative. This significant step brought together around fifty key stakeholders on November 11 to discuss strategies for accelerating change.

The discussions built on earlier work from the Foresight4Food FoSTr Programme in Jordan, including scenario analyses developed during previous workshops, computer modelling results, and a series of policy briefs. These resources provided a foundation for the day’s explorations into actionable pathways for transforming Jordan’s food systems.

A key highlight of the workshop was the collaborative spirit among diverse stakeholders. This environment fostered consensus-building around critical challenges and opportunities. Participants examined deep-seated barriers to change, focusing on economic and social incentives, the power dynamics of various actors, and entrenched mindsets that hinder progress.

Drawing from detailed policy briefs on topics such as vegetable and fruit markets, food governance, the role of the private sector, and the contributions of civil society, the workshop delved into strategies for enabling meaningful change.

Informed by the policy papers on vegetable and fruit markets, food governance, the role of the private sector and the role of civil society, the workshop looked more deeply into how change can be brought about.

One particularly impactful aspect was the use of computer modelling, conducted with Wageningen University and Research’s MAGNET model. This analysis demonstrated the potential consequences of continuing current practices (“business-as-usual”) versus adopting healthier, more sustainable pathways. Such data-driven insights are instrumental for policymakers, equipping them with evidence to support investments and policy reforms.

Beyond the workshop, conversations with Jordanian universities explored integrating foresight and systems thinking into academic curricula. Additionally, a dedicated training session provided researchers and policymakers with hands-on experience using the MAGNET model to analyze food system changes.

The workshops were made possible with support from the Jordanian Hashemite Fund for Human Development (JOHUD) and the National Alliance Against Hunger and Malnutrition (NAJMAH), underscoring the importance of partnerships in driving food systems transformation.

By Zoe Barois

Like many other countries, Bangladesh is working to develop it’s Food Systems Transformation Action Plan. This will be presented during the United Nations Food Systems Summit Plus 4 Stocktaking event. On November 6 and 7, Foresight4Food collaborated with GAIN Bangladesh to host a workshop on how foresight could contribute to the development of the Action Plan.

If transforming food systems were easy, it would have been done! But it’s not. Discussions dug into deeper questions about HOW change can be brought about and the implications of this for action in Bangladesh.

The participatory and dynamic workshop brought together policymakers, researchers, youth leaders, key UN organisations and members of the private sector. The workshop served two purposes, first to help clarify directions for the Action Plan, and secondly, to take forward the work on using foresight to help drive food systems change.

Discussion during the workshop focused on the five commitment pathways:

- Nourish all people

- Boost Nature-based Solutions

- Advance Equitable Livelihoods, Decent Work & Empowered Communities

- Build Resilience to Vulnerabilities, Shocks and Stresses and

- Accelerating the Means of Implementation

Validating scenarios for the future of food systems in Bangladesh

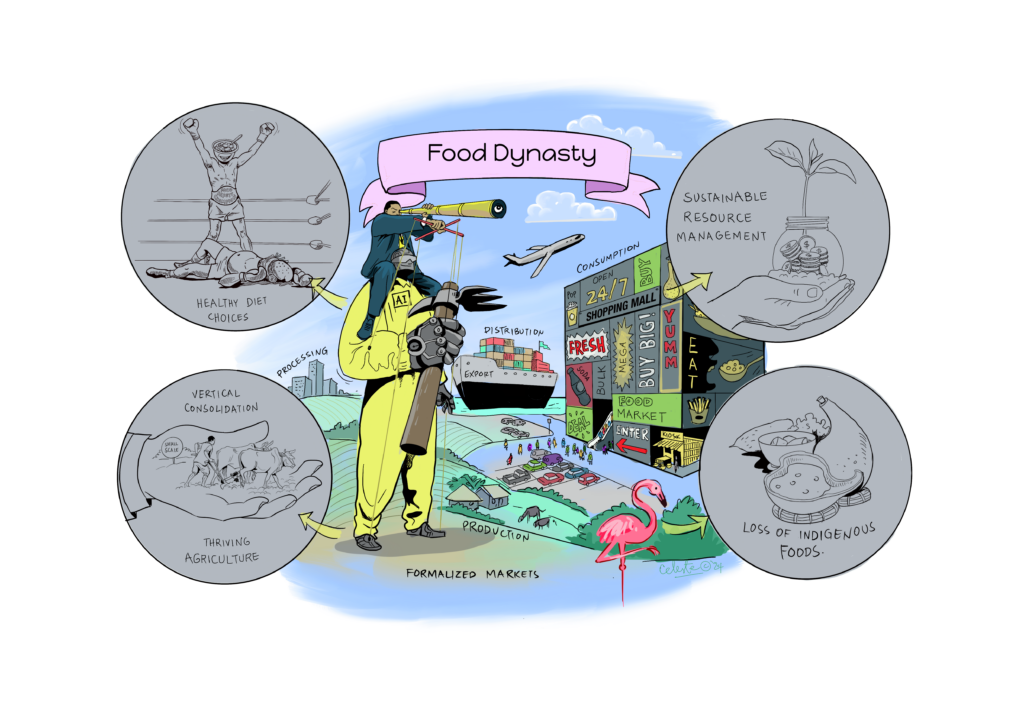

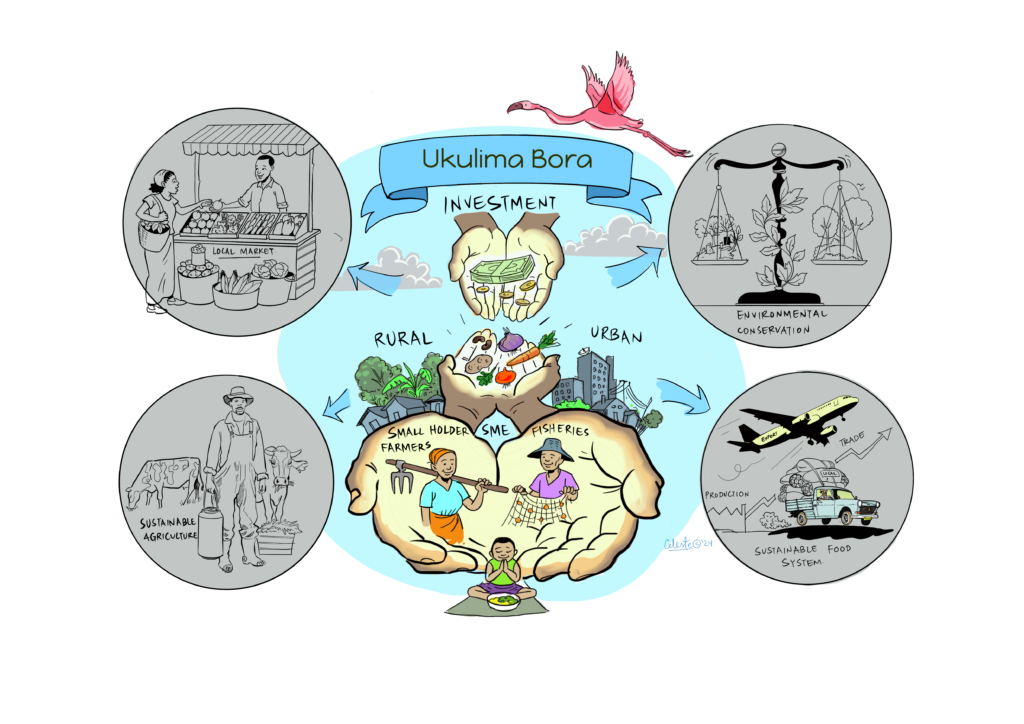

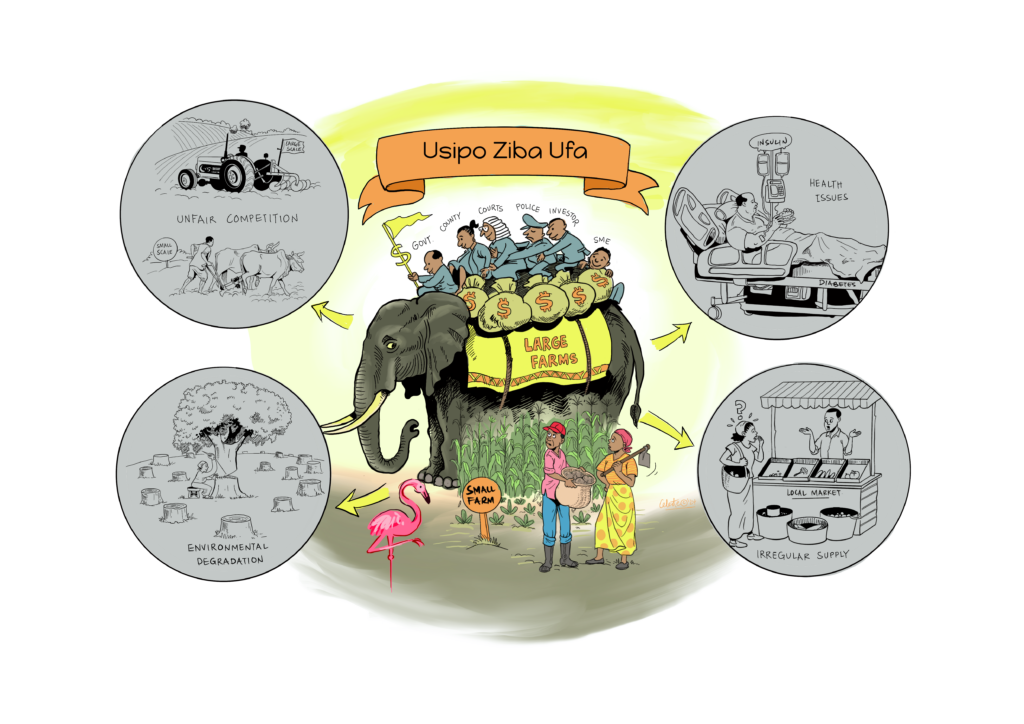

It was great to engage in discussions around four visual future scenarios. These were developed using rich pictures during a lively multistakeholder event in June earlier this year. Future scenarios are an excellent way to open discussions around what different stakeholders see as a desirable future. Interestingly, these do not always align as the implications would vary depending on what outcomes you’re seeking. At the end of the day, a poor farmer will desire different things when compared to a corrupt businessman!

The scenarios displayed different outcomes based on these uncertainties:

Equity – Would there be high or low levels of equity?

Climate resilience – we all know that climate change is happening, but whether Bangladesh will have high or low climate resilience is definitely in question

Healthy food consumption – Would people in Bangladesh be eating traditional diets or would they follow a diet that resembles something like a North American diet, something seen in many parts of the world.

Business structure – would Bangladesh have a diversified or consolidated business structure, dominated by a few large conglomerates

Creatively naming these scenarios helps convey the messages. So we had a fun exchange where groups came up with poetic Bangladeshi names to better describe the scenarios. Part of the validation will be to update these, helping spur action towards the most desired and away from the least desired future.

Unpacking five critical issues

Key issues blocking progress towards food systems change in Bangladesh relate to:

- The cost of a healthy diet in addressing malnutrition

- Climate resilience

- The role of social protection programmes in shaping food systems change

- Fruit and vegetable production

- Land use change and dietary patterns

These key themes were the result of a longer participatory process that emerged from the food systems map of Bangladesh. Diving into these topics, FoSTr’s five research partners shared their work on the key trends, challenges, and opportunities within each theme. Exploring these themes using a future lens can help clarify desired directions of change.

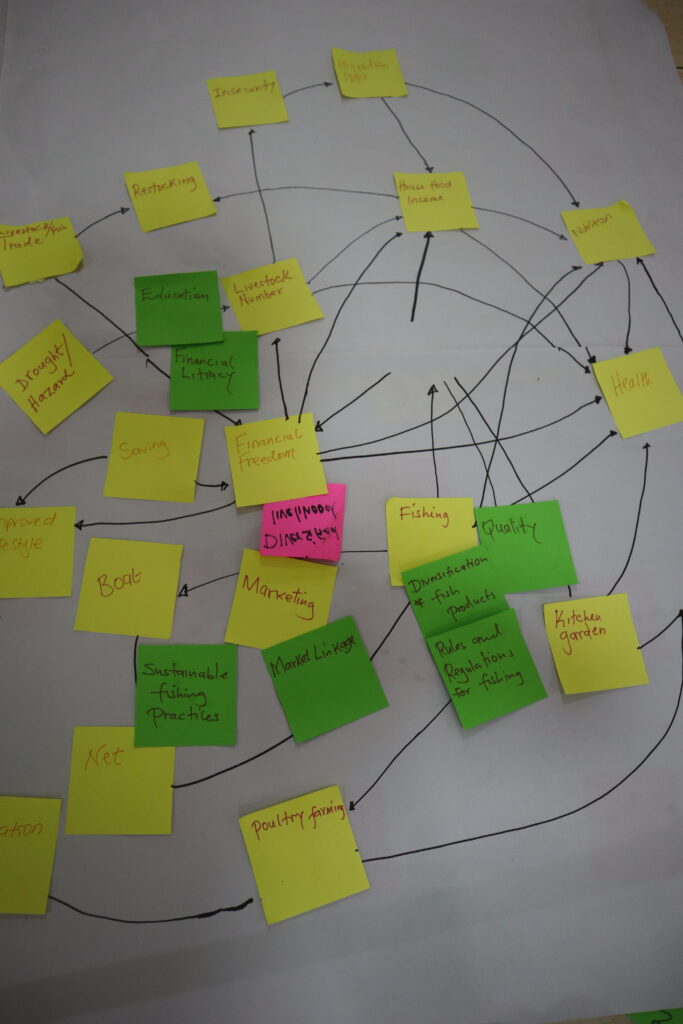

The power of causal loop mapping

How often do you get policymakers, youth and researchers around one table, heavily immersed in discussion using sticky notes and flip charts? My response: not often enough! This combination of actors is rarely seen but proves oh so valuable in uncovering insights previously hidden from each sector. The tool casual loop mapping, may be familiar to some. It’s a systems thinking tool where the interconnections between elements are mapped and the direction of causality identified. It’s a great way to map out the elements within a system and identify levers of change – small actions that lead to a large impact. For each of the commitment pathways, this casual loop mapping was performed. Insights like forming alliances between farmers and entrepreneurs to boost sustainable farming practices, or using the power of advertising to improve healthy food consumption and inspire healthy lifestyles were uncovered.

Reflections

Whilst having many people come together who don’t usually converse – the so-called ‘breaking the siloes’ is a huge achievement in itself, the task of writing yet another policy document looms above our heads. Everyone in the room has appeared here for a reason – which I hope is to create the change we need, a future that we all desire. After such positive discussions and recognition that we need to act – and act now, the fear I have is we will all fall into the same trap. The trap of being consumed by our busy agendas and becoming frustrated that yet another policy document has to be produced. Leading to un-actionable and hugely categorised actions. We don’t want this Plan of Action to become another document that has great suggestions but continues to lack the HOW. Let us think about how will these actions be implemented.

Foresight helps us to keep the bigger picture in mind, where do we want to go and where do we want to be in the future? Let’s use this thinking to help us prioritise and select key activities to implement. Working together to do so.

By Jim Woodhill, Lead Foresight4Food Initiative

Last week, I had the wonderful opportunity to support a regional training workshop on foresight for systems change in Nepal, in collaboration with the International Centre for Integrated Mountain Development (ICIMOD).

The workshop brought together a group of 35 development practitioners from across the Hindu Kush Himalaya region, including participants from Nepal, Bangladesh, Bhutan, India, and Pakistan. The focus was on how to use foresight to help tackle the big regional issues of climate adaptation, creating diversified and resilient livelihoods in mountain areas, migration, and disaster preparedness.

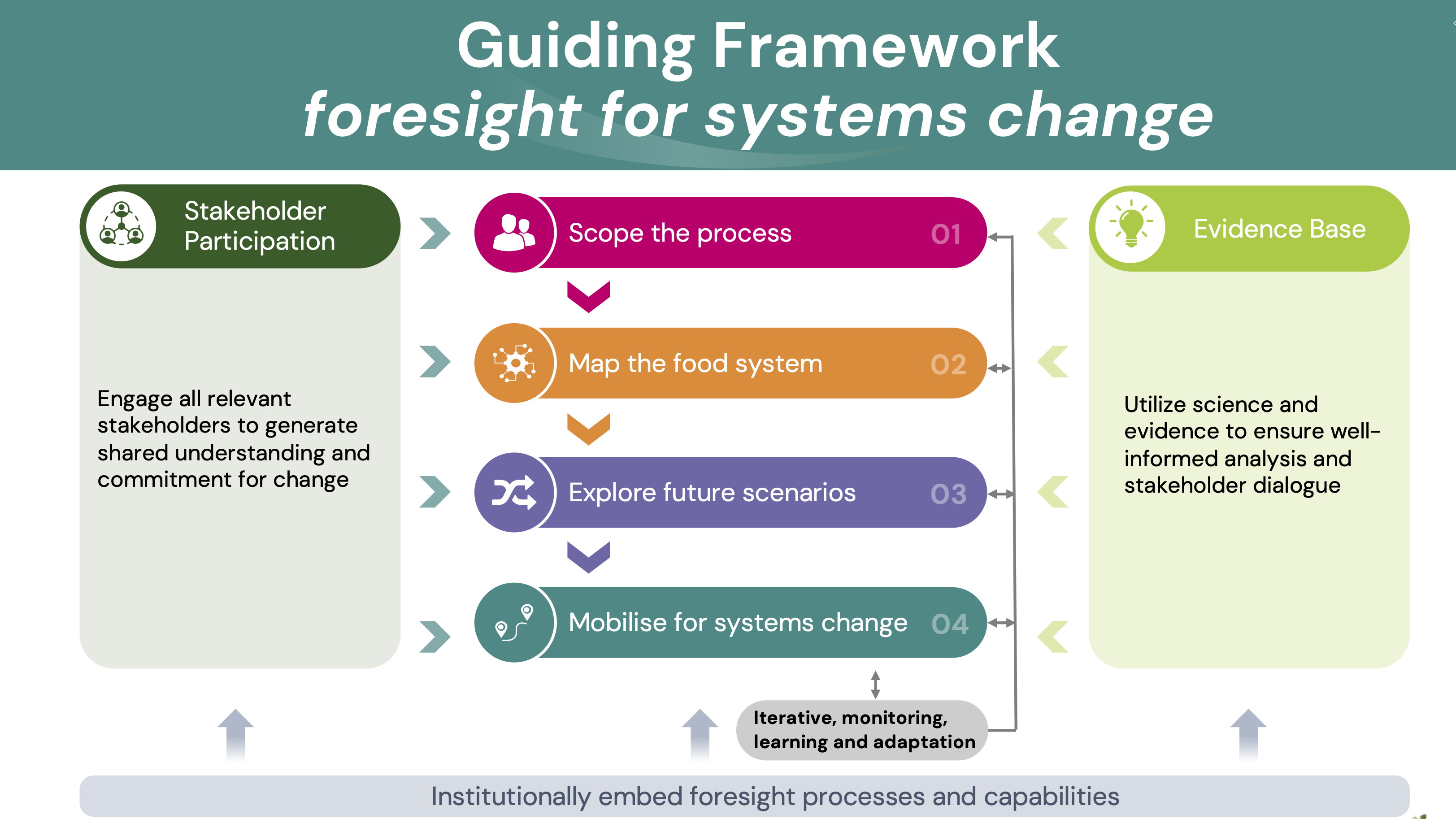

ICIMOD invited Foresight4Food to collaborate in facilitating the training, using Foresight4Food’s Framework of foresight for systems change following the organization’s participation in a similar leaders capacity development workshop held in Africa in 2023 (see report and video here) and Foresight4Food’s 4th Global Meeting in Bangladesh.

The Nepal event was a good chance to build on Foresight4Food’s capacity development experience in Kenya, Jordan, Bangladesh, and Uganda. These are focus countries for the Foresight for Food Systems Transformation (FoSTr) programme, supported by the International Fund for Agricultural Development with funding from the Dutch Government.

While food issues were only part of the focus of the workshop, the issues raised during the week yet again highlighted that the way food is consumed and produced is central to all development issues. Migration, climate adaptation, equitable livelihoods and managing disasters are all interconnected with agrifood systems.

What was covered in the training workshop?

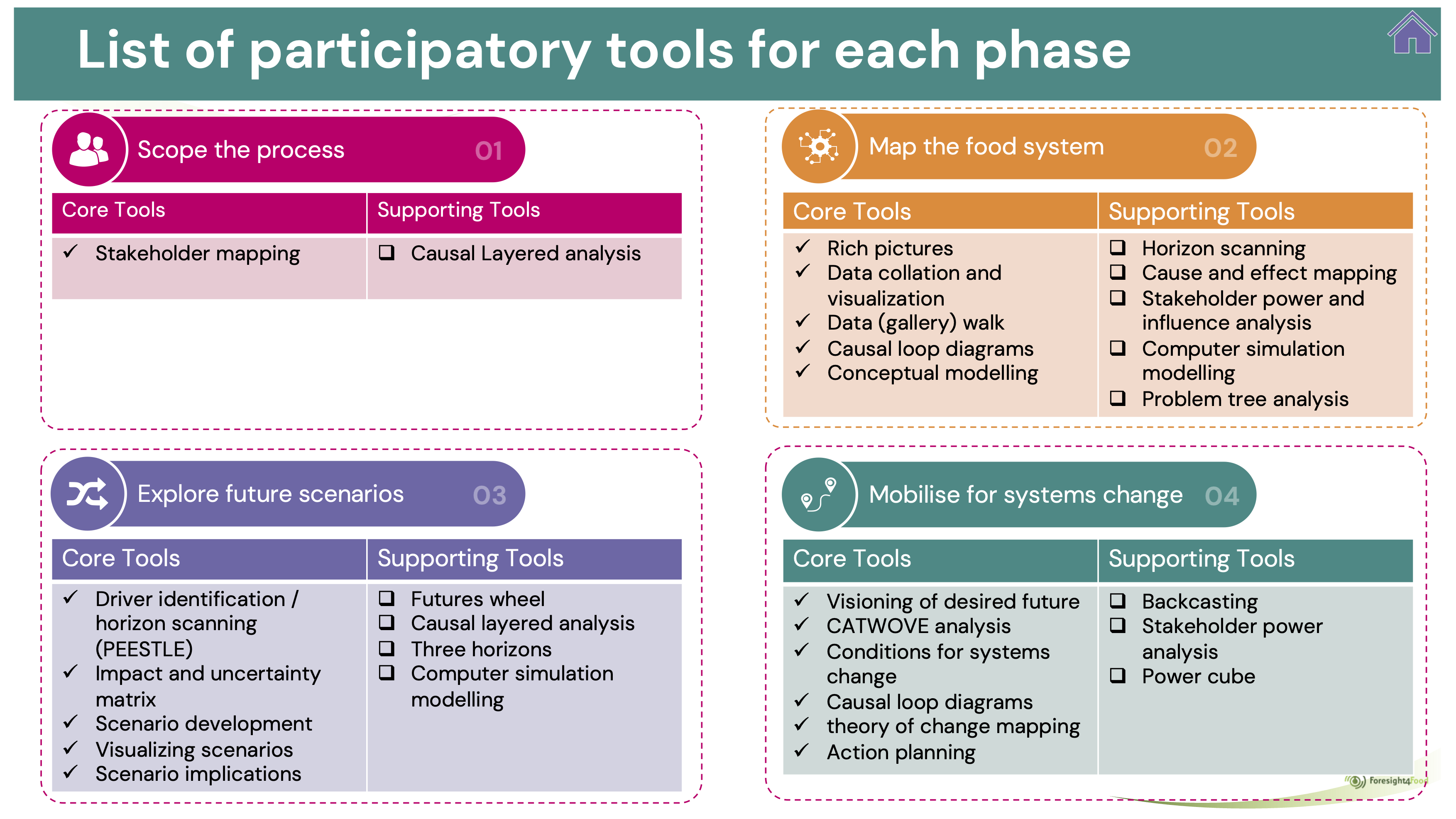

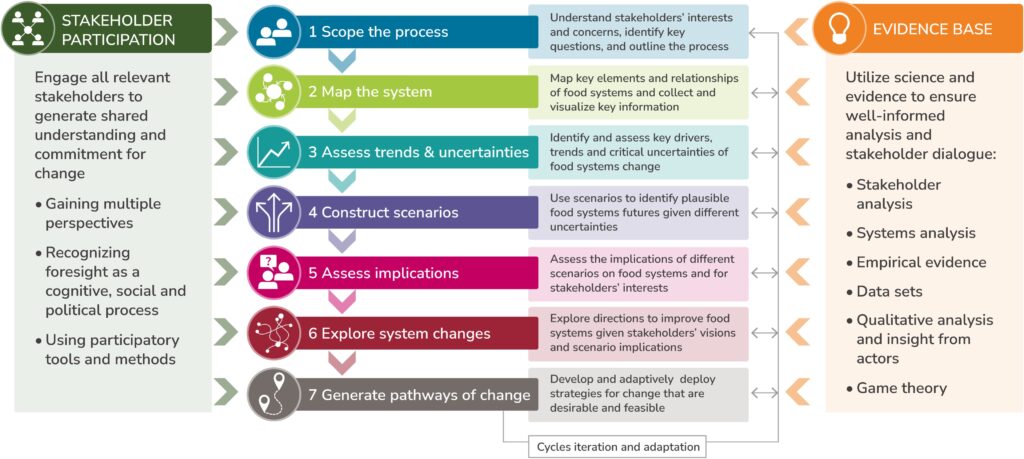

During the week, the participants worked through the four main phases of the Foresight4Food Framework:

- Scoping the process

- Mapping the system

- Exploring future scenarios

- Mobilising for systems change

For each phase, participants were introduced to background concepts and theory, and relevant participatory foresight and systems thinking tools. Rich pictures, drawn by participants to illustrate the whole system, is always a favourite. Other tools we worked with included horizon scanning of future trends and uncertainties (guided by the PEESTLE acronym), data exploration, causal loop diagrams, scenario development, visioning, back casting and conceptual modelling of systems.

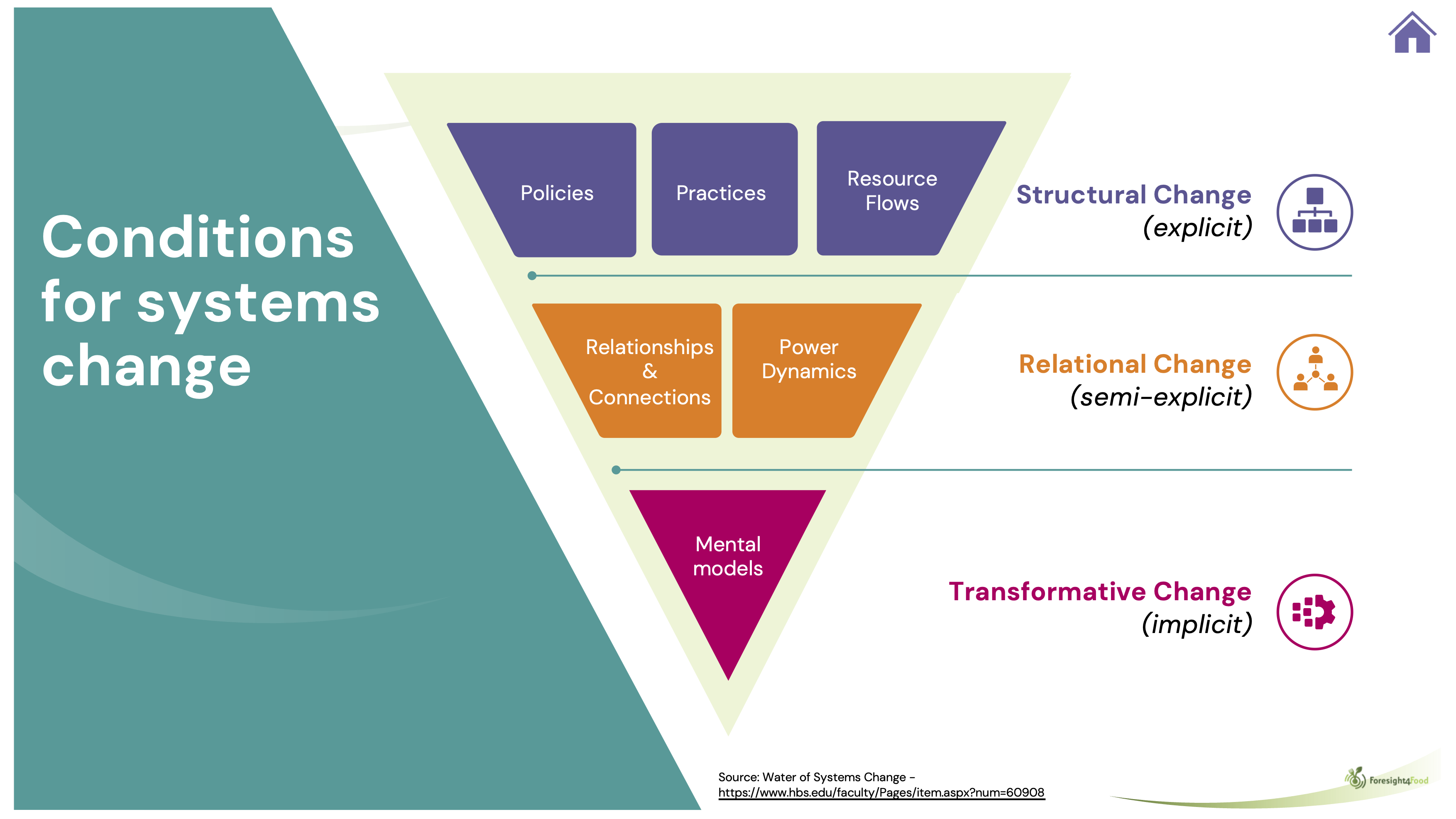

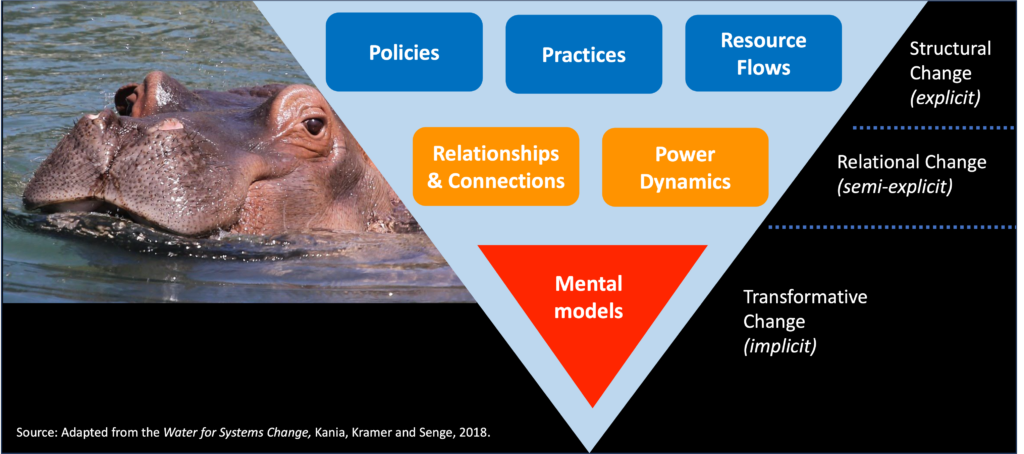

We discussed how change happens in complex adaptive (human) systems. The systems change “triangle” helped thinking about the role that mindsets and different forms of social and political power play in enabling or constraining change. The importance of bringing a gender equity and social inclusion (GESI) perspective to foresight was highlighted.

Participants applied their learning directly to the issues of climate adaptation, pastoralism, migration, and disaster preparedness.

The need for foresight

The global polycrisis is having a big impact on the Himalayas. The confluence of climate change, conflict, disease risk, inequality, biodiversity loss and geopolitical instability are bringing high levels of uncertainty and turbulence for citizens, businesses and governments across the region. For example, the melting of glaciers and the impact of extreme rainfall has profound implications for life in the mountains as well as for the billions of people who depend on the river systems that flow out of the Himalayas.

The Himalayas sit in the middle of a region with significant political tensions and shifting powers, which has major implications for the collaborative governance needed to effectively respond.

Foresight for systems change can help communities, organisations and governments better anticipate future risks and reimagine the future, so as to be more adaptive and resilient.

Thinking ‘out of the box’ – Foresight or “shortsight”?

Challenging discussions emerged during the week about how to ensure that foresight processes don’t just end up with the same old stuff – “old wine in new bottles”. To avoid this, we explored the need for “out of the box” thinking. This means looking for weak signals that might indicate a coming disruption, challenging assumptions about the future, bringing different perspectives to the table, using creative techniques to imagine radically different futures, and using the insights of “futurists”. A comprehensive horizon scanning process that explores mega-trends, trends, weak signals, critical uncertainties and wildcards helps to ensure foresight rather than “shortsight”.

Beyond tokenistic stakeholder participation

Across the Himalayas, it is local communities, local government and local businesses who must cope with the direct impact of floods, extreme heat, price fluctuations or disease outbreaks. Time and again participants returned to the importance of engaging local stakeholders to understand the challenges, and to generate pathways for greater resilience.

The discussion led to a shared understanding that this kind of participation from stakeholders requires genuine and open dialogue, made possible by using participatory workshop tools and techniques. However, all too often stakeholder engagement processes, when they do happen, fall back to formalised meeting structures, with speeches and presentations by “important” people, with little or no use of the sort of participatory analysis and dialogues tools participants engaged in during the training week. Advocating for effective, participatory and transformative stakeholder engagement processes is an obvious role for ICIMOD.

Institutional barriers to foresight and systemic practice

At the end of the week participants explored how to use foresight and systems thinking and practice in their own working context. Then some of the realities hit home.

Funders and donors often still force very linear, short-term and inflexible modes of programme design and management. Policymakers struggle to work effectively in a cross-ministerial way. People who see themselves as “senior” resist rolling up their sleeves and actively engaging in participatory processes with other stakeholders. Response strategies often stick to the safe space of technical analysis and technical solutions ignoring how mindsets and power structures block transformational change.

These are challenges that organisations like ICIMOD and initiatives like Foresight4Food need to help tackle if foresight is to have a real impact on policy and local action.

Cultivating a cadre of foresight and systems change practitioners

Participants recognised there is a limited number of practitioners/professionals across the region who have the knowledge, skills and experience to effectively design and facilitate foresight and systems change processes. A big effort is needed to create a cadre of practitioners who do have these capabilities.

To tackle this gap, governments can develop foresight units, universities could make futures literacy and systems thinking part of their curriculum, and development organisations need to in invest more in such human capabilities.

Way forward

On the last day of the workshop, the “collective intelligence” of participants was used to start framing a new horizon scan for the region that could follow up on the highly influential 2019 HIMAP report on the region.

Participants left with many practical ideas of how they could apply the foresight thinking and tools directly to their work.

For ICIMOD and Foresight4Food hopefully, this was just the start of collaborating to strengthen regional capacities for foresight.

The energy and commitment of participants were astounding, especially given long days of challenging discussions.

All in all, it was a super inspiring week – giving hope that with committed people like those in the workshop, supported by organisations like ICIMOD, we can together create a more resilient and equitable future.

By Bram Peters

The Foresight4Food FoSTr team has just returned from an active and productive trip to Kenya, despite the challenging political situation in the country. From our perspective, this highlights the need to adapt to turbulence and to use foresight to build resilience for Kenya’s food system.

From June 19 to 26, together with my team members including Jim Woodhill, Herman Brouwer, and Wangeci Gitata-Kiriga we conducted a range of food systems foresight workshops in Nairobi and Nakuru with a wide range of national food systems stakeholders. Here is a brief update on the action.

Navigating turbulence

On the morning of June 19, Foresight4Food, together with partners ILRI–CGIAR, Results for Africa Initiative and University of Nairobi, organised two sessions in Nairobi. The interactive breakfast session was all about ‘Navigating agri-business in turbulent futures’. The session was co-hosted by IFAD Kenya and was attended by a range of private sector associations, business support services, innovation facilitators and impact investors.

The focus of the meeting was to introduce the topic of foresight in relation to agribusiness in Kenya, share some of the scenarios that were developed in the context of Nakuru, and discuss the implications of different futures of the food system. Participants were shown five different scenarios of how the food system might look in 2040 in Nakuru and were invited to think through and discuss the implications of these scenarios.

With a strong presence and involvement of leaders from various private sector associations such as the Agriculture Sector Network (ASNET) of the Kenya Private Sector Alliance, the discussion invited stakeholders to reflect not only on trends and uncertainties emerging in Kenya, but also how their own businesses are preparing for the future.

Supporting the pathways for food system transformation

In the afternoon of June 19, the FoSTr team organised a national update session on the progress of FoSTr since June 2023. The session was attended by many individuals from the morning session, as well as representatives from government, civil society and research organisations. The FoSTr team presented the latest updates, including the launch of a ‘Kenya Food Systems Mapping Report’, and with a collection of scenarios for the Nakuru food system.

With a special presentation by the Ministry of Agriculture and the Food Systems Technical Working Group and special remarks from IFAD on the 3FS tool, it was discussed how a wide range of ecosystem support initiatives are buttressing the national food systems transformation pathways in Kenya. The approach by Foresight4Food to engage with two counties, Nakuru and Marsabit, and to build on Bottom-up initiatives showed how our approach complements the ongoing national-level initiatives.

Systemic Theory of Change

From June 19 to 21, the Foresight4Food FoSTr team facilitated a 3-day workshop for the inception phase of the new Netherlands-funded, World Food Programme and UNESCO on ‘Sustainably Unlocking the Potential of Lake Turkana. Stakeholder representatives from the Lake Turkana region (both on the Marsabit and Turkana sides of the lake) gathered in Nairobi to engage in a shared analysis of the complex food system and co-create the high-level focus of the programme.

The Turkana Lake food system is highly complex, with high food insecurity, vulnerability to climate change and conflict, and many cultural dynamics around pastoralist and fisheries livelihoods. Finding market opportunities and strengthening resilience is not easy, and requires a different way of working. Using the Foresight4Food approach, and building on 6 scenarios that were developed in previous workshops in Marsabit and Turkana, stakeholders explored what might need to be done to understand systemic risks and how lasting opportunities can be triggered.

Preparing a Systemic ToC is all about analysing the context, articulating the transformations needed in light of various future scenarios, and developing the building blocks for action. The building blocks include pathways, processes and partnerships. Through many interactive discussions and exercises, the stakeholders conducted value chain mapping of the fish value chain, CATWOVE for articulating systemic change narratives, and Causal Loop Mapping.

Manifesto for Change for the Nakuru Food System

On June 24 and 25, the FoSTr team including partners ILRI-CGIAR, Results for Africa Initiative and University of Nairobi once again visited Nakuru, now to explore systemic change pathways. As we already noted from previous workshops, the food system of Nakuru County is full of potential, as Nakuru’s natural resources are rich and a wide range of agricultural value chains are represented. However, challenges related to food and nutrition security and environmental sustainability exist. Trends of climate change, unhealthy diets and land fragmentation are appearing. The future holds many uncertainties. In order to future-proof the food system, it is urgent that investments are made to further enhance the resilience and sustainability of food and agriculture in Nakuru.

Since November 2023, a diverse group of more than 40 different stakeholders from Nakuru county have been coming together to consider the future of food system, supported by researchers and facilitators of Foresight4Food. This inclusive group looked at the challenges and opportunities for food and agriculture today and how they might evolve in 10-15 years. Food system analysis, an assessment of drivers and trends relevant to Nakuru, and 5 scenarios were developed by this group.

During these two days, stakeholders from Nakuru engaged in scenario interpretation and Causal Loop diagramming to come up with key pathways to kickstart food system transformation in Nakuru. These outputs culminated in a Manifesto for Change: a vision for the desired future for Nakuru’s food system and a range of possible pathways that can set us in that direction, while preparing us for a range of uncertainties. The Manifesto calls upon all stakeholders to join and align their actions, and intensify collaboration to transform Nakuru’s food system so that it can feed its people nutritiously; advance economic development; restore balance with nature; grow in-county revenue and eventually GDP growth for Kenya.

The preparations for the 4th Global Foresight4Food Workshop are well underway. A diverse group of participants are expected to join and use this opportunity to share their ideas and insights as well as connect with a growing community of foresight practitioners. In regard to this, we asked Dr. Rathana Peou Norbert-Munns, Sustainable Development, Agrifood System Policies and Climate Foresight Planning Specialist at FAO and a valuable member of the Foresight4Food steering group to share some thoughts and her expectations from the workshop.

The biggest challenge our world is facing that keeps me up at night…

If I had to pinpoint the most significant challenge, it would undoubtedly be climate change. However, as a foresight planning specialist, I’d say that a forward-thinking planning approach helps various stakeholders recognize not only the widely acknowledged issues but also those that are just beginning to emerge, the so-called early signals. These insights enable us to map out risks across multiple time horizons and envision plausible futures and encourage us to rethink our current actions and adopt innovative approaches which are urgently need it. Ultimately, while these concerns sometime disrupt my sleep, it definitely fuels my daily actions with a clear, long-term vision for sustainable change.

What I look forward to in the 4th Global Foresight4Food workshop

My expectations are set high to leverage the tool of Foresight for Food System Transformation effectively. In a global polycrisis, there is a pressing need for innovative and strategic thinking to guide decisions that ensure sustainable food systems.

This year’s theme of the Foresight4Food Global Workshop captures the essence of what we aim to achieve: a shift in how we envision and shape the future of food systems. It promises to be a crucial platform for sharing insights, fostering collaborative efforts, and enhancing the capabilities of practitioners through knowledge exchange and community building. It is an opportunity to connect with a diverse network of experts and stakeholders, all driven by the common goal of transforming food systems for a better future. By creating a safe space for discussion and reflection, the workshop will challenge us to consider innovative accelerators for our work and identify necessary changes in our approaches.

“This year’s theme of the Foresight4Food Global Workshop captures the essence of what we aim to achieve: a shift in how we envision and shape the future of food systems.”

The workshop will also allow us to critically assess vested interests within the food systems, ensuring that our solutions are inclusive and equitable, truly embodying the principle of leaving no one behind.

On a personal level, I expect that the insights I’ll gain from the workshop will be integral to refining approaches developed for key programs in the Asia Pacific region. By learning the latest foresight methodologies and emerging trends, I aim to reflect with an increasing community of practitioners and find avenue to collaborate more effectively with stakeholders to implement resilient and sustainable food policies and practices.

Some ways to make the workshop more effective, my two cents

To ensure the workshop has a lasting impact on cross-sector collaborations and actions towards food system transformation, Foresight4Food must foster an environment of honesty where participants feel secure in openly sharing both challenges and innovative ideas. Encouraging creative and bold thinking is essential, as it will drive the development of groundbreaking strategies that transcend traditional sector boundaries and catalyze meaningful changes through transformative foresight.

by Bram Peters

As a part of the FoSTr programme, the Foresight4Food team organized the “Exploring Alternative Futures for Jordan’s Food System” workshop in Amman, Jordan that brought together food systems stakeholders in Amman to discuss the future of Jordan’s food security. Here are some of the observations and insights from the event.

With themes of resilience, adaptation, action, and collaboration, participants engaged in scenario planning and back-casting exercises to anticipate challenges and shape future outcomes. Key uncertainties like water availability, healthy diets, regional trade, and business structures were explored through four scenarios set in 2040. These insights, supported by quantitative modeling, fostered rich discussions about desirable futures and the actions needed today to create a sustainable, resilient food system for Jordan.

During the workshop, colleagues from the University of Jordan and Jordan University of Science and Technology presented four policy briefs. These were: Food Loss and Waste, Water-to-Food Conversion, State of Smallholder Farming in Jordan and Malnutrition. Each policy brief captures the state of knowledge and offers recommendations to explore how to address these issues from a food systems perspective.

The FoSTr team introduced four critical uncertainties that will be highly important and uncertain to the long-term future of the Jordan food system:

- The extent of fresh water available to agriculture

- The extent to which healthy diets are adopted

- Level of ease of regional trade

- The type of business structure the food system will have

Each of these uncertainties was combined to offer four scenarios, taking place in 2040, up for discussion with the participants. Supported by insights from quantitative simulation modelling, the implications on food systems outcomes were explored in each scenario. Some scenarios described that the people of Jordan adopt healthy diets despite a challenging regional trade situation. In others, severe limitations on fresh water for agriculture were seen in combination with a highly corporate-led food system.

Additionally, the participants explored how that situation might look in each. These scenarios served to open up minds towards the possibility of different situations emerging in the future and highlight the need for anticipatory action and systemic change.

The scenarios led to a discussion of what might be the ‘most likely‘ and ‘most desirable’ scenarios for the Jordan food systems stakeholders. The outline of a desirable future, informed by trends and uncertainties, was formulated to serve as a guiding star. A back-casting approach was used to then explore what events and turning points might occur between 2040 and now to realise that desired future. Based on this timeline, stakeholders brainstormed a range of different actions and stakeholders which are needed now, to already start pushing the system towards the Desired Future.

Building on the encouraging shared co-ownership of the results of the workshop, the Foresight4Food FoSTr team will continue efforts to develop policy briefs, deepen the action areas that were developed, and support the Food Security Council of Jordan in proving the underpinnings for the ongoing work on national food systems transformation.

By Bram Peters – Food Systems Programme Facilitator, Foresight4Food

In the north of Kenya, on the border with Ethiopia, the landscape is expansive and dry. Pastoralism is the main source of livelihood, but to the west of this landscape is Lake Turkana, one of the largest saline desert lakes of the world. Here communities engage, some productively and others reluctantly and out of desperation, in fishing.

In March 2024, the Foresight4Food FoSTr team traveled to the fascinating Kenyan county of Marsabit to facilitate a multi-stakeholder forum to support the co-creation of the new ‘Sustainably Unlocking the Economic Potential of Lake Turkana’ programme.

In Marsabit, stakeholders from around the Turkana Lake, including fishers, traders, service providers, county government technical officers, and non-governmental organizations, came together to analyze the context and co-create future scenarios and intervention areas for a new WFP and UNESCO programme, funded by the Embassy of the Kingdom of the Netherlands.

Together with the World Food Programme and the World Food Programme Innovation team, the FoSTr team held a highly interactive and productive three-day workshop. As most stakeholders mainly spoke Kiswahili, we switched to short presentations with much emphasis on interactive group work. On the first day, the workshop focused on contextual understanding of the Lake Turkana food system as well as the Marsabit county livelihoods, using the Rich Picture mapping exercise. Participants together drew the food system, the geography of the lake, but also the stakeholders, activities, key relations and dynamics.

On the second day, the groups presented their deep knowledge of the context to each other and elaborated on this. Workshop participants tackled key trends shaping the food and livelihoods system: groups discussed how various themes (for example: lake water levels, fish stocks to income sources, conflict, and education) changed over time and what they expect to happen 10 years into the future. Important in this discussion is their analysis of what driving issues would influence change in the future.

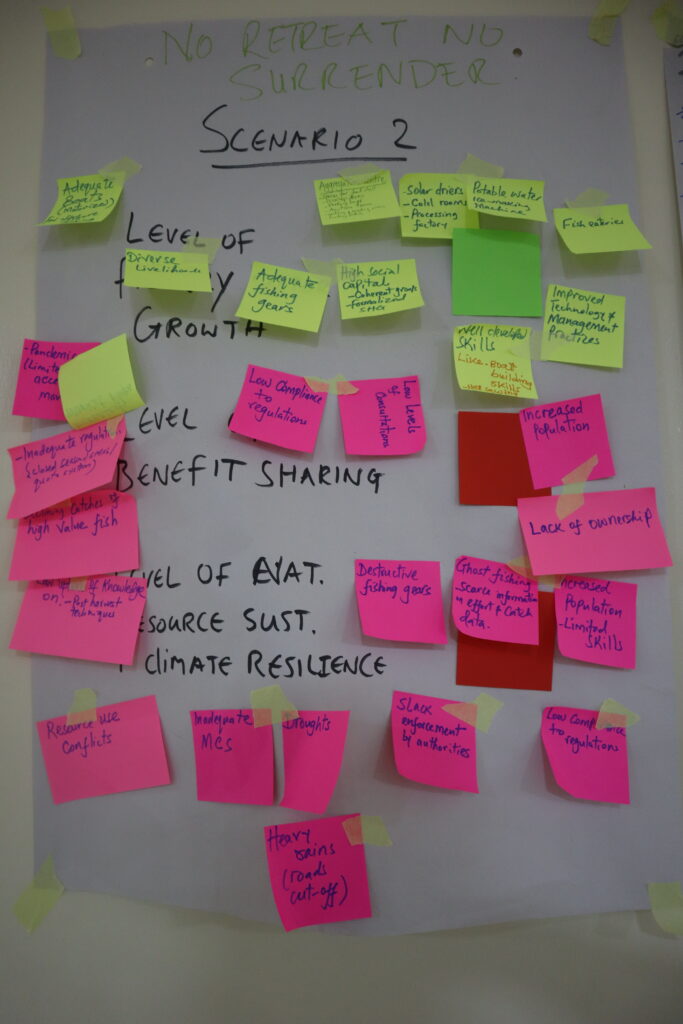

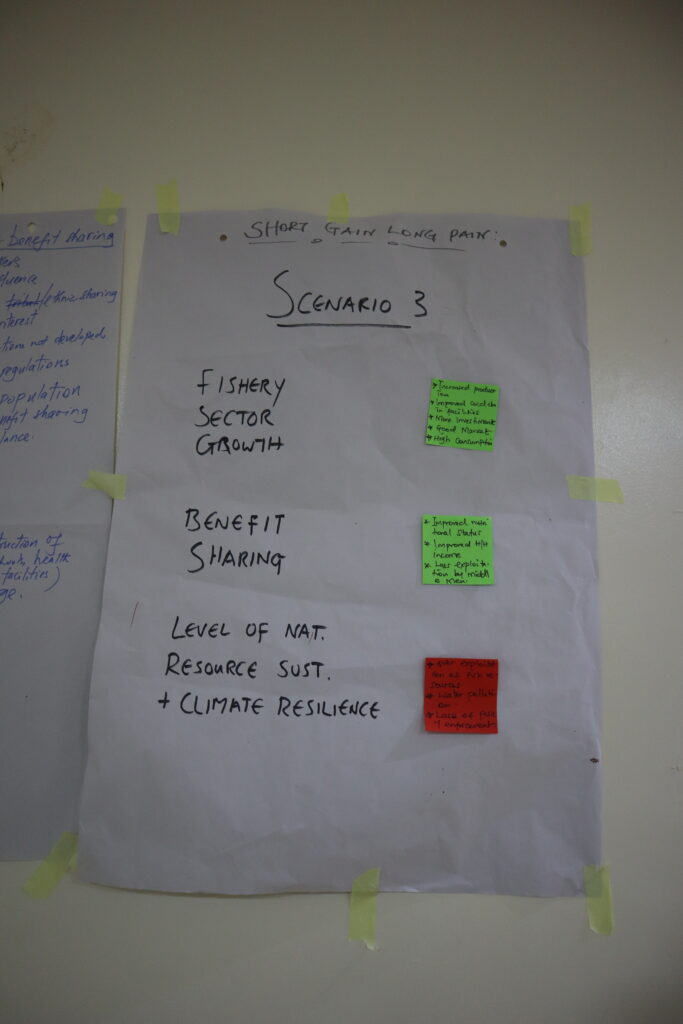

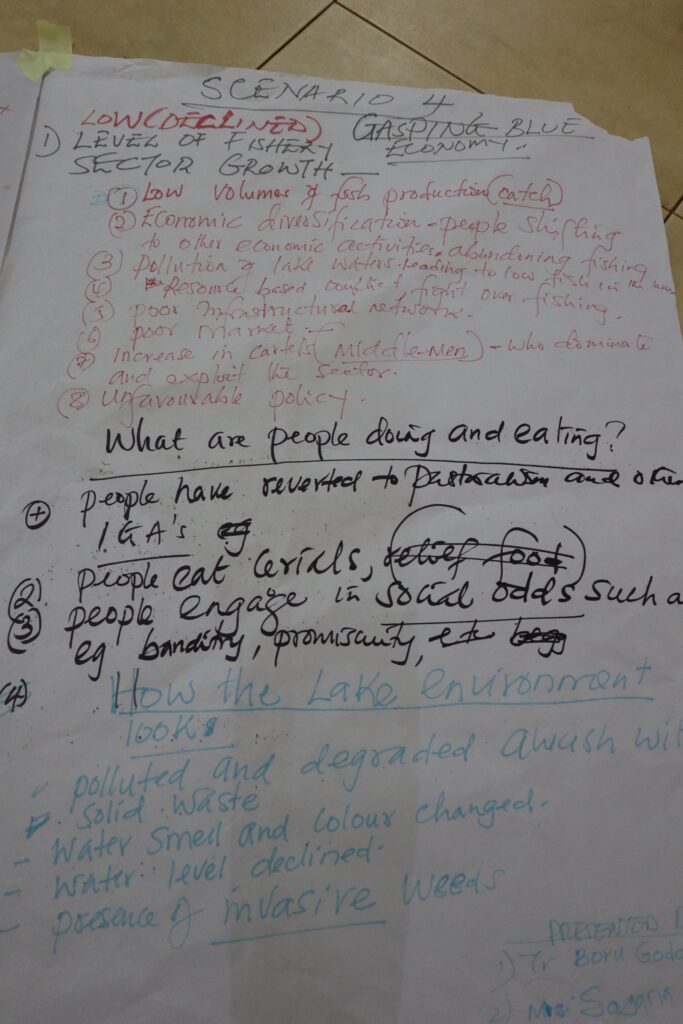

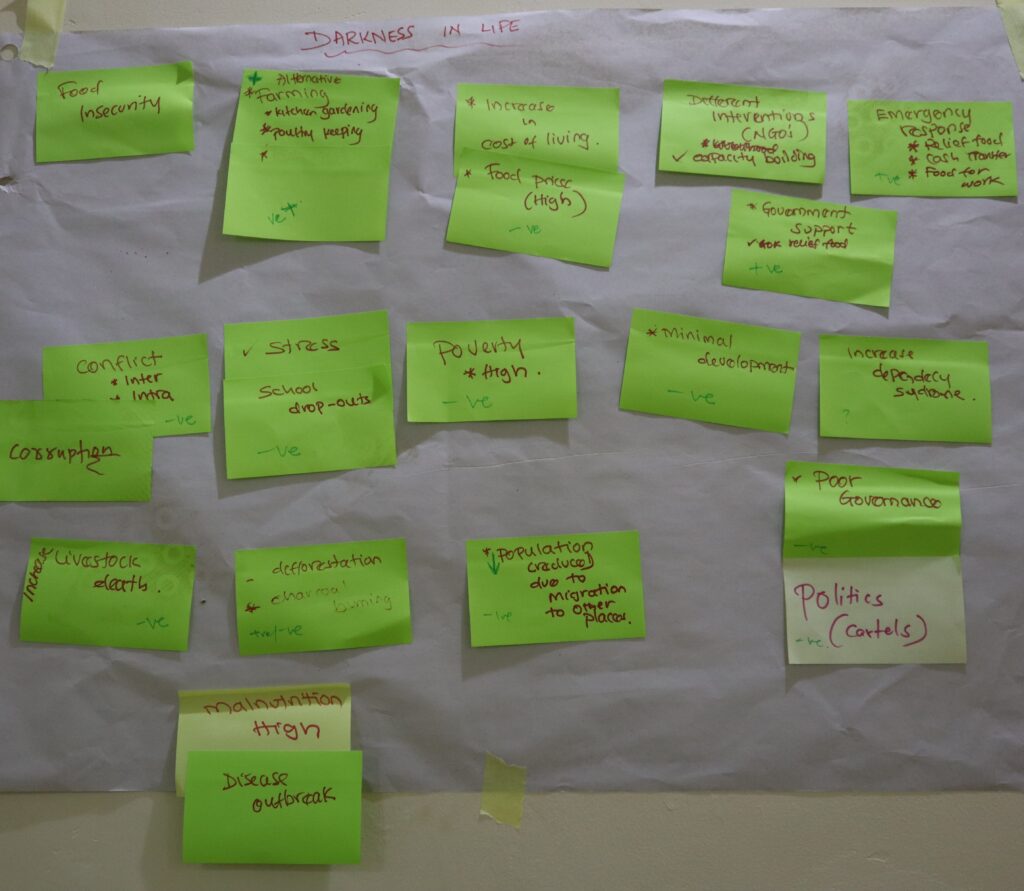

5 scenarios were created for the future regarding the fisheries sector and supporting livelihoods, as well as an in-depth discussion on key entry points for intervention in the system. These scenarios had names that described these futures succinctly:

- ‘Tumaini Paradiso’, a future with a growing fishing sector, inclusive benefit sharing and sustainable natural resource management;

- ‘No retreat, no surrender’, a situation in which the benefits of a growing fisheries sector are controlled by a few;

- ‘Short gain, long pain’, a scenario where the fisheries sector grows and livelihoods improve around the lake, but the environment is not maintained;

- ‘Gasping blue economy but others rise’, is a future where the fisheries sector remains marginal for communities, but other sectors are developed that also contribute to inclusive development and environmental sustainability

- ‘Darkness in life’, a bleak outlook where none of the envisioned sustainable economic development around the lake delivers and where climate resilience is low, and conflict is rife.

Different stakeholders participating in the workshop had different opinions on the likelihood of certain scenarios emerging. Some imagined the situation worsening, while a few viewed the future more positively. These reflections clearly showed a combination of outlook of participants as well as the signals they interpret from the current situation and the trends seen now. Interestingly, none of the stakeholders felt the ‘Paradiso’ scenario was likely, showing that the programme needs to be modest in its systemic ambitions, but also be ready to do things very differently. These scenarios showed what could become a very relevant frame of reference to the stakeholders as well as the programme implementors.

On the last day of the workshop, participants explored a common vision for the future, and how the food system is currently working. This led stakeholders to have a first try at exploring what is needed to change that system toward the common vision.

At the end of the workshop, I felt highly positive about these fruitful discussions that enabled participants to think about what might happen to the Marsabit food system in the years to come, and what factors would influence these changes. In addition to that, the insights gathered through the multi-stakeholder forum are expected to not only support the inception phase of the programme but will also support multi-stakeholder engagement throughout the programme.

The Foresight4Food FoSTr team will continue to support the World Food Programme team in realizing the ‘Sustainably Unlocking the Economic Potential of Lake Turkana’ programme inception phase. A follow-up workshop will take place in Turkana County from March 25 to 28, with stakeholders from that side of Lake Turkana.

By Jim Woodhill, Foresight4Food Initiative Lead

Last month (November 2023) I had the wonderful experience of engaging with over fifty young leaders from across Africa, joined by colleagues from Bangladesh, Nepal, and Jordan. We had all gathered in Naivasha, Kenya, to explore how skills in facilitating foresight can be used to help bring about food systems transformation.

The fascinating work these young leaders are involved in and their deep interest in understanding how to be more effective change-makers was truly inspiring. It was encouraging to see how valuable they found the foresight for the food systems change framework and the associated set of participatory tools for engaging stakeholders.

Participants all came with projects from their own countries where they are keen to use foresight and systems thinking to help facilitate change in food systems by bringing together different stakeholders. The participants were from diverse backgrounds representing policy, the private sector, NGOs, and academia.

A Guiding Framework: During the workshop we introduced participants to an overall guiding framework for facilitating foresight for food systems change. A range of participatory tools were used for systems analysis, development of future scenarios and exploring systemic interventions. To bring reality into the workshop, the Kenya horticulture sector was used as a case study for the foresight analysis. Participants spent a day visiting horticulture farms, packing and processing facilities and the local market. They explored with local stakeholders how they saw the future for the horticulture sector and the issues that “keep them awake at night”.

Visualising the system: The workshop was highly interactive with participants practicing in the facilitation of a range of participatory tools which can be used to bring stakeholders into dialogue around systems change. One of my favourite participatory tools “rich picturing”, which enables a diverse group of stakeholders to develop a shared understanding of a system by drawing it, was found by participants to be especially powerful.

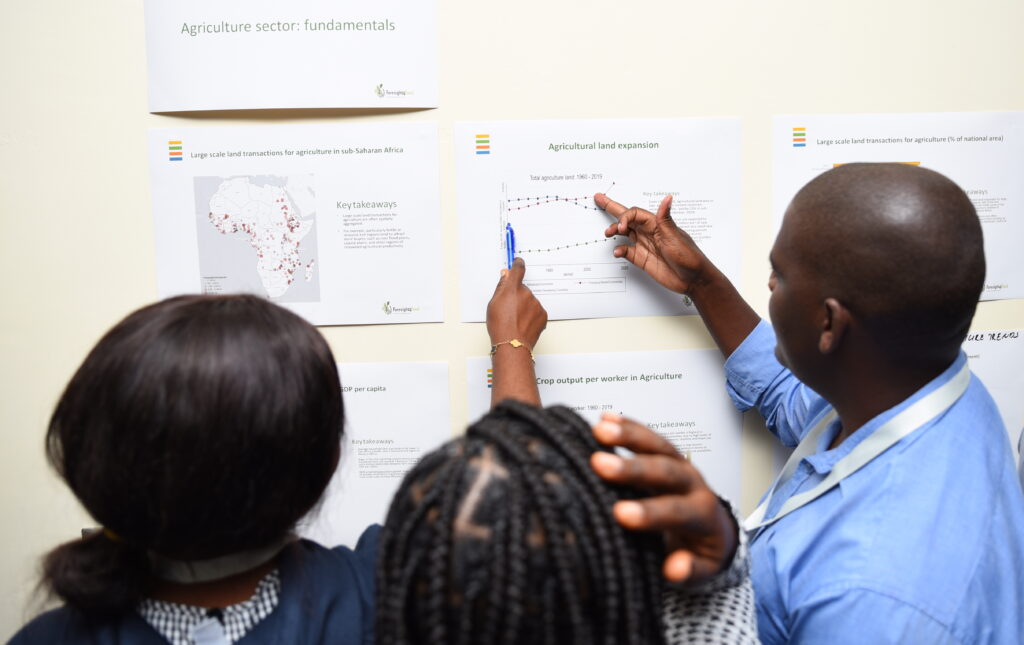

Data-driven dialogue: To go deeper into the systems analysis it is valuable for stakeholders to explore the available data on key drivers and trends. Over 100 graphs visualizing key data points related to the Kenya horticulture sector and food systems at national, continental, and global scales were collated and posted around the walls. The participants then explored this data in groups of three and discussed its implications and how it perhaps challenged their existing assumptions.

Exploring the future using scenarios: Central to the foresight approach is developing a range of different plausible future scenarios (generally with a 10 to 30-year horizon) for how the system might evolve given critical uncertainties. Workshop participants did this for the horticulture sector, looking at factors such as how diets might change in the future, regional and global trading relations, severity of climate change, and the enabling policy environment for small-scale producers and the small- and medium-scale enterprises (SME) sector. The scenarios help to identify future risks and opportunities for different stakeholder groups and society at large. They also help to unlock creative thinking about how to “nudge” systems towards more desirable futures and away from less desirable ones.

The deeper issues of systems change: It is easy to talk about systems change. In reality trying to change systems bumps into all the difficult issues of vested interests, power relations, ideologies, and deeply held cultural beliefs. On top of this human and natural systems are complex and adaptive and behave in self-organising, dynamic, and often unpredictable ways. It doesn’t mean you can’t intervene to try and bring positive change. But it does mean that top-down, linear, and mechanistic models of change generally don’t work. The workshop engaged participants in deep and challenging discussions about what it means to be a leader of systems change. This included the need to be adaptive, how to create alliances for disrupting existing power relations, the importance of building relations between diverse stakeholders, and the importance of patience. Systems change often requires taking time to build the foundations for change without being able to know when circumstances might suddenly unlock opportunities for big steps forward.

Identifying directions for change and intervention options: Developing directions and pathways for systems change is the most difficult and challenging part of the foresight for systems change process. It is highly context-specific and requires a deep insight into the political economy of the situation. Cause and effect mapping, theory of change thinking, and causal loop analysis can all help in identifying opportunities for intervening which could help to drive systems change in desired directions. Bringing change will often require an integrated approach to technological, institutional and political innovation. During the workshop causal loop diagrams were used to explore possible entry points for shifting horticulture systems in ways that could improve health, livelihoods and the environment.

New friends, new networks and big ambitions: After an intense week of learning and sharing participants left inspired to apply the foresight approach back in their own work environment. New friends were made and there were clear calls to find mechanisms to support ongoing networking and peer support.

Many thanks to the facilitation and support team who made a fantastic week possible, Gosia McFarlane, Marie Parramon-Gurney, Kristin Muthui, Bram Peters, Joost Guijt, Riti Herman Mostert, and Abdulrazak Ibrahim. The event was made possible by support from the Mastercard Foundation.

More information about the Foresight4Food Framework of Foresight for Food Systems Change can be found on our website, and an updated approach paper will be published in January 2024.