By Bram Peters

The future of food systems is uncertain, yet one thing is clear—transformative change is urgently needed. Climate change, inequality, and geopolitical instability are reshaping how food is produced, distributed, and consumed. How can we navigate these complexities and create a more sustainable, resilient food system?

At the Power of Foresight Workshop held on 30-31 January 2025 at the FAO headquarters in Rome, experts and practitioners gathered to discuss how foresight can drive food systems transformation. Their insights reveal a crucial truth: the process itself— working with complexity, embracing inclusivity, diverse perspectives, and collective intelligence—is central to making real progress.

Insights from the ‘Power of Foresight’ Workshop

- 17 different cases and the stories of 48 participants from 27 countries demonstrated that foresight approaches have much to offer to the process of food systems transformation

- Working with complex systems is what it’s about, and effective foresight practices for food systems change to embrace this

- Openness to new and inclusive perspectives should be central to all foresight for food systems transformation efforts

- The process brings the answer – and foresight can bring awareness of crucial process elements such as collective intelligence, agency, time and scale

- Embracing the ‘ifs’: how you do foresight, and what comes before and after, is just as important as the development of scenarios

- Foresight is not one approach or one methodology – there are a diversity of ways to go about it

- The national food systems pathways can benefit from foresight approaches

Photos: 30 January 2025, Foresight4Food workshop. FAO Headquarters, Rome. Photo credit: ©️FAO/Cristiano Minichiello

Working with complex systems: Let’s talk about the elephants in the room

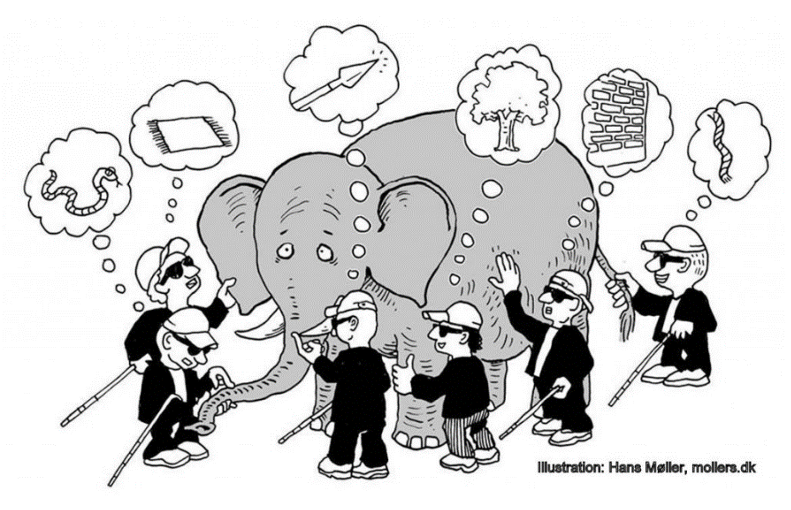

When it comes to food systems transformation, there isn’t just one elephant in the room—there are many. These metaphorical elephants represent the complex, interconnected challenges we face, and ignoring them only hinders progress.

- First, as a whole range of interrelated challenges and assumptions we are not working on enough: whether that’s climate change, human rights, global geopolitical turbulence, growing inequality. All these challenges together form a context of global polycrisis.

- Second, we can see elephants in the room related to our apparent inability to take decisive transformative action in food systems: a lot of talk, limited action.

- Finally, we can see elephants as representing systems. An elephant can represent a dynamic, complex food system, of which we might only be able to see or understand the trunk, tusks, ears or tail.

Like the elephant and the blind men metaphor (see image to the right), food systems are deeply interconnected with global issues like climate change, inequality, and geopolitical instability. Tackling these requires a holistic approach, recognizing that transformation cannot happen in silos.

Gather new and inclusive perspectives – and change your own

What’s central to talking about complex food systems is perspective. We all have different mental images of food systems—whether local agriculture, marine ecosystems, or trade networks. Expanding our perspectives helps identify new entry points for addressing issues like malnutrition, poverty, and sustainability.

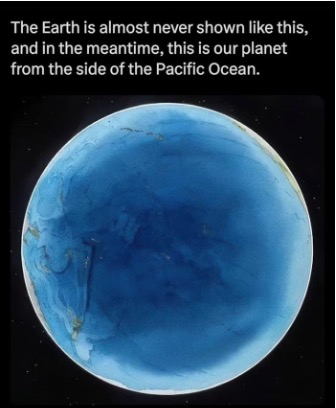

For some, like from the Pacific region, it’s about marine ecosystems in which food is central. Changing your perspective can be a helpful way of looking at a complex topic: such as to see the Pacific food system composed not of ‘small island states’ but rather ‘large ocean states’ connected with the global food system through trade, governance, and oceanic currents. Why is flipping your perspective so important? It helps to reframe entry points for discussion with other stakeholders and view the root causes of things like malnutrition, non-communicable diseases, poverty and human rights abuse in food systems differently.

If you are able to change your perspective, it helps to understand the viewpoints of those less heard. Having an inclusive process to gather different viewpoints is crucial to changing perspectives and behaviour, mobilising for collective action and creating shared visions of the future.

The process is the answer

Ever tried herding cats? Well, transforming food systems is about fostering C.A.T.S.—a process centred on:

- Collective intelligence – Multi-stakeholder collaboration and co-creation

- Agency – Empowering change through action

- Time – Bridging past, present, and future

- Scale – Recognizing interconnections between local and global systems

So, what does it mean to herd cats when talking about food systems? It means there are no magic bullets: the process is central to the outcome.

Effort on addressing the ‘ifs’

Foresight can be of great added value to support the food systems transformation process. Whether it is about co-creating alternative futures, conducting backcasting towards a more desirable scenario, highlighting the cost of delayed action, or informing anticipatory policy – foresight and scenario tools are a key toolbox in the hands of systems change champions.

In order for foresight to be effective, there are a number of conditional ‘ifs’ i.e., if foresight experts and facilitators:

- Are able to move beyond added value, tackling pre-conditions, obstacles, and constraints affecting how stakeholders prepare for the future.

- Not only preach to the converted – we need to involve stakeholders who think and act differently

- Are cognizant of power differences, lock-ins and political economy

- Build on other approaches that also provide value, such as design thinking, human-centred development and mission-oriented policy making.

- Pay attention to what comes before and after the development of scenarios

Scenarios only developed from the perspective of single organisations or without meaningful consultation and dialogue will not be effective.

Foresight approaches and national food systems pathways

There are a broad range of foresight approaches, some expert-driven or participatory, others quantitative, experiential, creative or analytical. Each has their value – but these needs come from a clear user need and scope within a food system. However, it is essential to keep in mind that foresight is a tool, not a panacea, and cannot address all questions.

With 156 national convenors driving progress through implementing 137 national food systems transformation pathways, the upcoming UNFSS+4 Stocktaking Moment (July, Addis Ababa) presents an opportunity to share lessons and strengthen impact. What we have seen the past two days in Rome, is the incredible richness and diversity of initiatives that use foresight to support the food systems transformation process.

Sharing the lessons from these initiatives, communicating the potential of foresight, and supporting the national convenors to further realise the impact on transforming food systems outcomes will be crucial in the run-up to the Stocktaking Moment.