By Jim Woodhill, Lead Foresight4Food Initiative

Last week, I had the wonderful opportunity to support a regional training workshop on foresight for systems change in Nepal, in collaboration with the International Centre for Integrated Mountain Development (ICIMOD).

The workshop brought together a group of 35 development practitioners from across the Hindu Kush Himalaya region, including participants from Nepal, Bangladesh, Bhutan, India, and Pakistan. The focus was on how to use foresight to help tackle the big regional issues of climate adaptation, creating diversified and resilient livelihoods in mountain areas, migration, and disaster preparedness.

ICIMOD invited Foresight4Food to collaborate in facilitating the training, using Foresight4Food’s Framework of foresight for systems change following the organization’s participation in a similar leaders capacity development workshop held in Africa in 2023 (see report and video here) and Foresight4Food’s 4th Global Meeting in Bangladesh.

The Nepal event was a good chance to build on Foresight4Food’s capacity development experience in Kenya, Jordan, Bangladesh, and Uganda. These are focus countries for the Foresight for Food Systems Transformation (FoSTr) programme, supported by the International Fund for Agricultural Development with funding from the Dutch Government.

While food issues were only part of the focus of the workshop, the issues raised during the week yet again highlighted that the way food is consumed and produced is central to all development issues. Migration, climate adaptation, equitable livelihoods and managing disasters are all interconnected with agrifood systems.

What was covered in the training workshop?

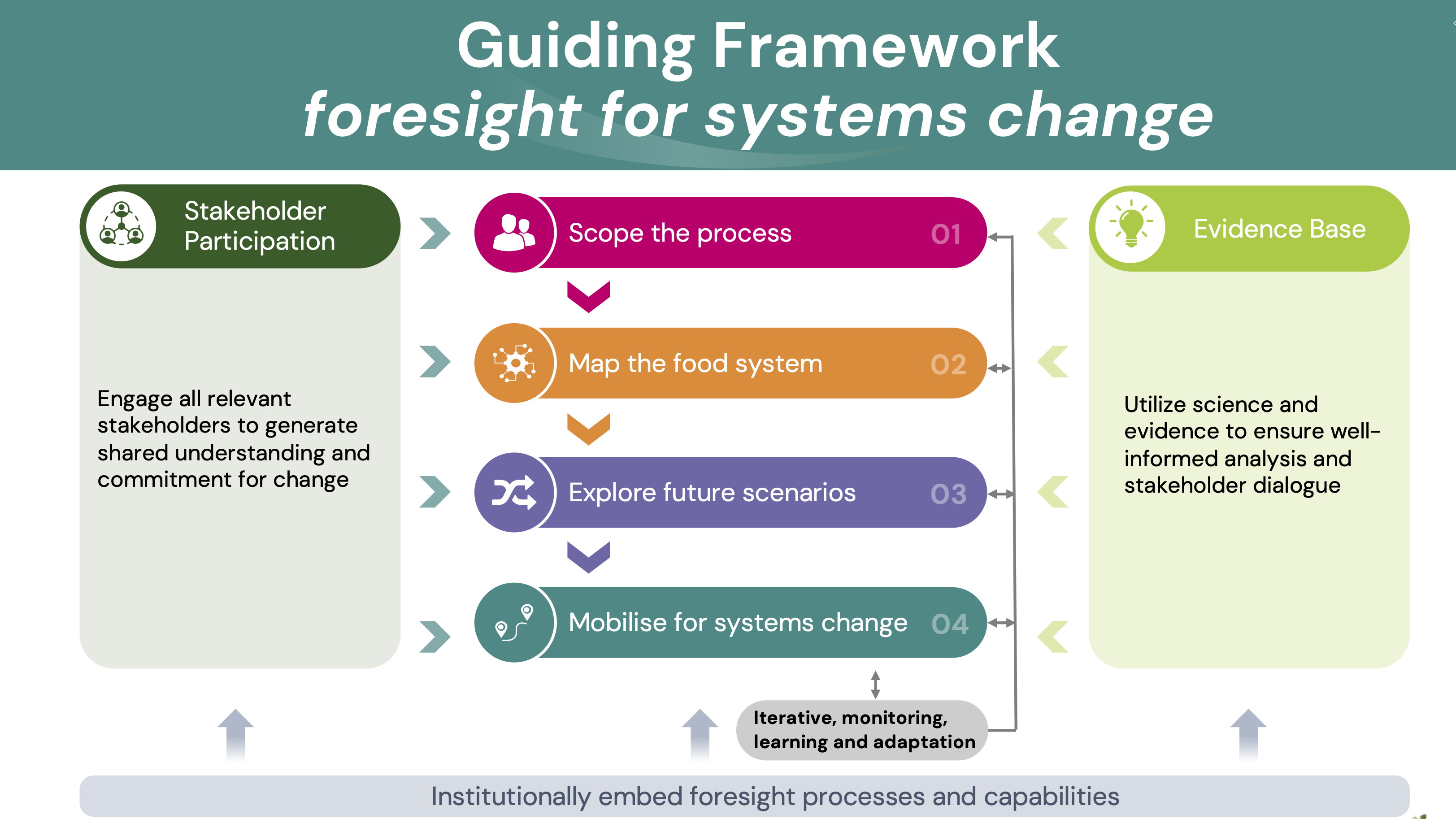

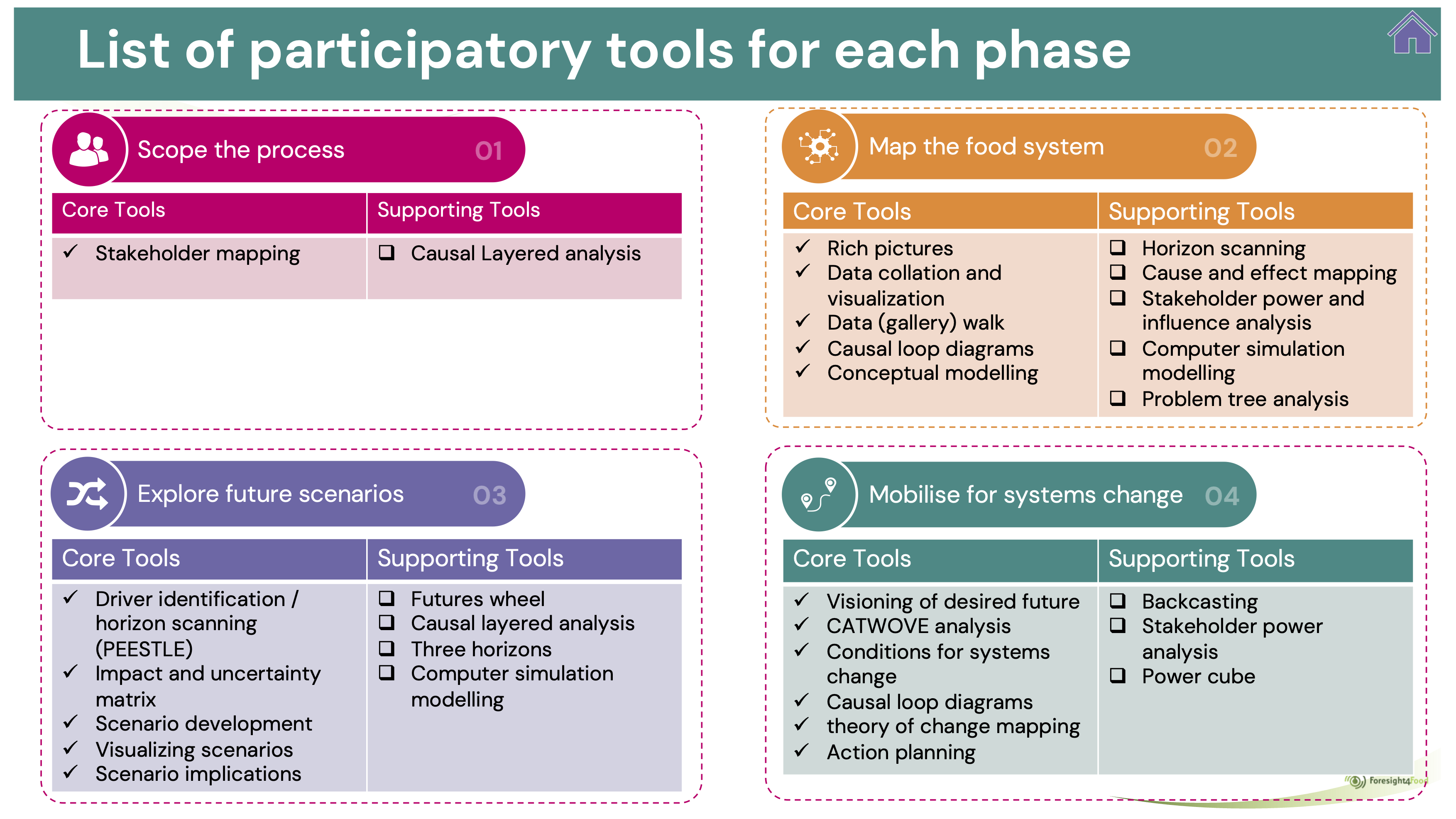

During the week, the participants worked through the four main phases of the Foresight4Food Framework:

- Scoping the process

- Mapping the system

- Exploring future scenarios

- Mobilising for systems change

For each phase, participants were introduced to background concepts and theory, and relevant participatory foresight and systems thinking tools. Rich pictures, drawn by participants to illustrate the whole system, is always a favourite. Other tools we worked with included horizon scanning of future trends and uncertainties (guided by the PEESTLE acronym), data exploration, causal loop diagrams, scenario development, visioning, back casting and conceptual modelling of systems.

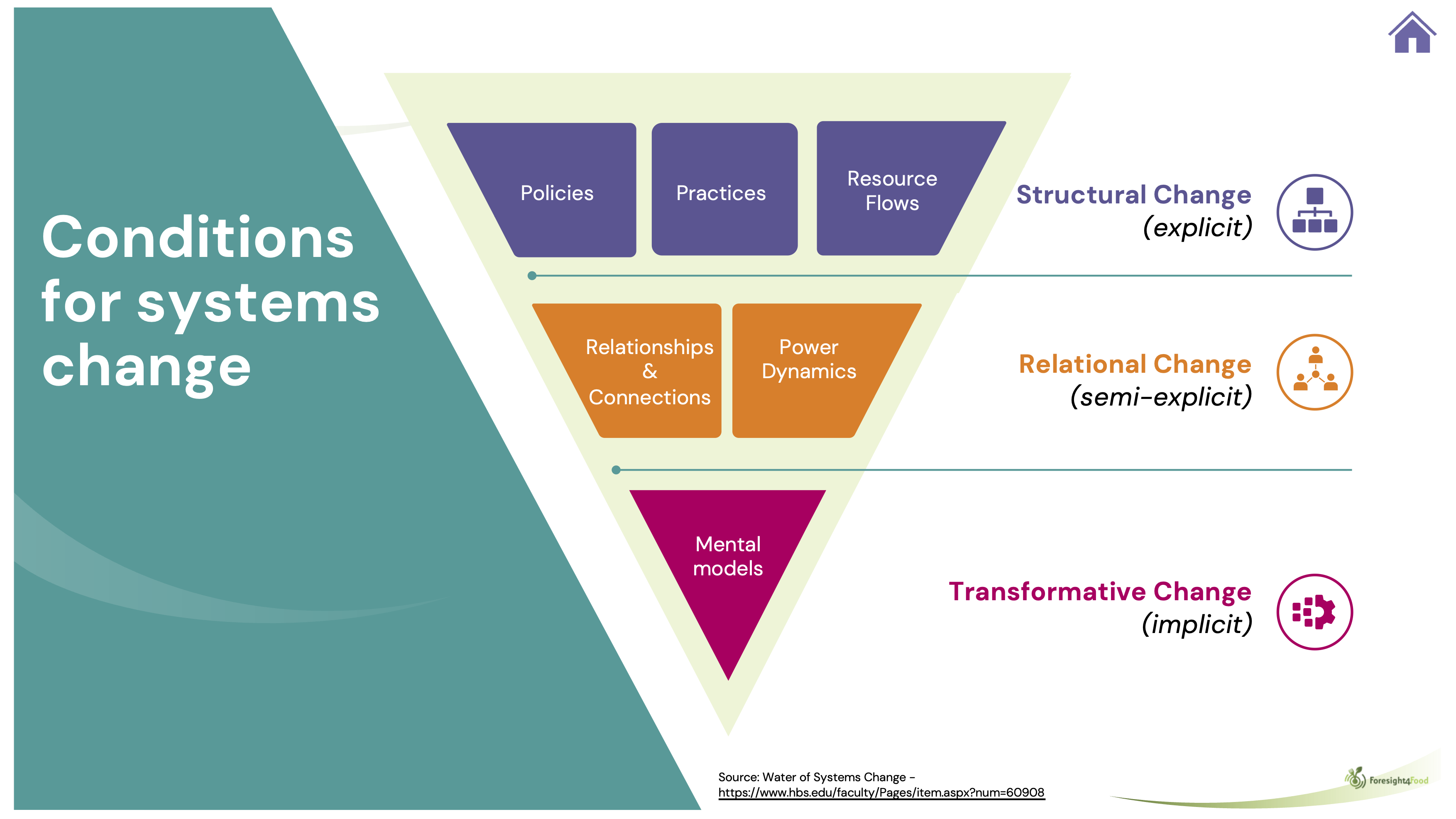

We discussed how change happens in complex adaptive (human) systems. The systems change “triangle” helped thinking about the role that mindsets and different forms of social and political power play in enabling or constraining change. The importance of bringing a gender equity and social inclusion (GESI) perspective to foresight was highlighted.

Participants applied their learning directly to the issues of climate adaptation, pastoralism, migration, and disaster preparedness.

The need for foresight

The global polycrisis is having a big impact on the Himalayas. The confluence of climate change, conflict, disease risk, inequality, biodiversity loss and geopolitical instability are bringing high levels of uncertainty and turbulence for citizens, businesses and governments across the region. For example, the melting of glaciers and the impact of extreme rainfall has profound implications for life in the mountains as well as for the billions of people who depend on the river systems that flow out of the Himalayas.

The Himalayas sit in the middle of a region with significant political tensions and shifting powers, which has major implications for the collaborative governance needed to effectively respond.

Foresight for systems change can help communities, organisations and governments better anticipate future risks and reimagine the future, so as to be more adaptive and resilient.

Thinking ‘out of the box’ – Foresight or “shortsight”?

Challenging discussions emerged during the week about how to ensure that foresight processes don’t just end up with the same old stuff – “old wine in new bottles”. To avoid this, we explored the need for “out of the box” thinking. This means looking for weak signals that might indicate a coming disruption, challenging assumptions about the future, bringing different perspectives to the table, using creative techniques to imagine radically different futures, and using the insights of “futurists”. A comprehensive horizon scanning process that explores mega-trends, trends, weak signals, critical uncertainties and wildcards helps to ensure foresight rather than “shortsight”.

Beyond tokenistic stakeholder participation

Across the Himalayas, it is local communities, local government and local businesses who must cope with the direct impact of floods, extreme heat, price fluctuations or disease outbreaks. Time and again participants returned to the importance of engaging local stakeholders to understand the challenges, and to generate pathways for greater resilience.

The discussion led to a shared understanding that this kind of participation from stakeholders requires genuine and open dialogue, made possible by using participatory workshop tools and techniques. However, all too often stakeholder engagement processes, when they do happen, fall back to formalised meeting structures, with speeches and presentations by “important” people, with little or no use of the sort of participatory analysis and dialogues tools participants engaged in during the training week. Advocating for effective, participatory and transformative stakeholder engagement processes is an obvious role for ICIMOD.

Institutional barriers to foresight and systemic practice

At the end of the week participants explored how to use foresight and systems thinking and practice in their own working context. Then some of the realities hit home.

Funders and donors often still force very linear, short-term and inflexible modes of programme design and management. Policymakers struggle to work effectively in a cross-ministerial way. People who see themselves as “senior” resist rolling up their sleeves and actively engaging in participatory processes with other stakeholders. Response strategies often stick to the safe space of technical analysis and technical solutions ignoring how mindsets and power structures block transformational change.

These are challenges that organisations like ICIMOD and initiatives like Foresight4Food need to help tackle if foresight is to have a real impact on policy and local action.

Cultivating a cadre of foresight and systems change practitioners

Participants recognised there is a limited number of practitioners/professionals across the region who have the knowledge, skills and experience to effectively design and facilitate foresight and systems change processes. A big effort is needed to create a cadre of practitioners who do have these capabilities.

To tackle this gap, governments can develop foresight units, universities could make futures literacy and systems thinking part of their curriculum, and development organisations need to in invest more in such human capabilities.

Way forward

On the last day of the workshop, the “collective intelligence” of participants was used to start framing a new horizon scan for the region that could follow up on the highly influential 2019 HIMAP report on the region.

Participants left with many practical ideas of how they could apply the foresight thinking and tools directly to their work.

For ICIMOD and Foresight4Food hopefully, this was just the start of collaborating to strengthen regional capacities for foresight.

The energy and commitment of participants were astounding, especially given long days of challenging discussions.

All in all, it was a super inspiring week – giving hope that with committed people like those in the workshop, supported by organisations like ICIMOD, we can together create a more resilient and equitable future.

By Just Dengerink

Foresight training for Africa Foresight Academy by Foresight4Food researchers and Wageningen University & Research (WUR)

The Foresight4Food initiative aims to connect and inspire networks of foresight professionals around the world. In early July 2022, members of the Africa Foresight Academy participated in a foresight training at Oxford, provided by Foresight4Food researchers from the University of Oxford’s Environmental Change Institute (ECI) in collaboration with Wageningen University & Research (WUR). The training was attended by five African researchers in person, while five others joined in online.

The Foresight4Food ‘seven steps’ approach to scenario and foresight analysis (see illustration below) was used to develop four scenarios for a more climate-resilient Ghana in 2040. Here’s a look at how these scenarios were developed using the Foresight4Food approach in the training session.

Scoping the process and mapping the food system

The scenario exercise started with scoping and delineating the focus of the scenario process Collectively, it was decided to focus the scenarios on the future of the Ghana food system in 2040, and the resilience of this system to external shocks related to climate change.

Participants were invited to draw a ‘rich picture’ of the Ghana food system to map out its most important features. These included small-scale yam and cocoa production in the south, maize and sorghum production in the north, fisheries along the coast and around Lake Volta along with the role of urban informal food markets, the lack of a large food processing sector, Covid-19’s impact on supply chains, growing security threats in the region, and the effect of the war in Ukraine on fuel prices and availability of fertilizers.

From assessing trends and uncertainties to constructing scenarios

Building upon the key features of the Ghana food system from the ‘rich picture’ exercise, participants were then invited to identify the most important trends and uncertainties affecting the Ghana food system.

Highlighted key trends included fast population growth and urbanization, increasing use of technology, growing dependence on food imports and remittances, decreasing occurrence of crop diseases, growing youth unemployment, and the increase in fast food consumption.

Together, the participants also identified some important uncertainties regarding the future of the Ghana food system: the degree of extreme weather events, the implementation efficiency of climate resilience policies, and the vulnerability of households to climate change. Other uncertainties identified included future access to fertilizers, fluctuations in fuel prices, changes in trade regimes, levels of agricultural productivity, the expected value of the Ghanaian currency, the potential influence of future Covid outbreaks and the impact of developments in the general security of the region.

The participants then decided on two key uncertainties that would be critical in determining the future climate resilience of the Ghanaian food system. Based on these two key uncertainties, a matrix was created with each of the axes representing one uncertainty. Within this matrix, four scenarios were constructed, based on their position on both axes and with input from the other uncertainties that were identified.

Assessing implications, exploring system changes and designing pathways

With the four scenarios in place, participants were invited to give more colour to these four plausible futures by exploring the implications of each scenario for different stakeholder groups. One group explored the implications for rural farmers, while the other focused on urban consumers.

With the implications of each scenario explored in more detail, participants were asked to zoom out and think about the possible system changes that – in each scenario – could contribute to a more climate-resilient future of the Ghanaian food system. Suggestions included the stimulation of climate-smart agriculture practices, diversification of production and dietary patterns, strengthening regional trade, supporting home gardens and peri-urban agriculture and digitalization of supply chain management.

This three-day exercise with African foresight experts showed how the Foresight4Food approach can help structure a participatory foresight process that leads to engaging scenarios and actionable policy recommendations to shape the future of our food systems.