By Jim Woodhill, Lead Foresight4Food Initiative

Last week, I had the wonderful opportunity to support a regional training workshop on foresight for systems change in Nepal, in collaboration with the International Centre for Integrated Mountain Development (ICIMOD).

The workshop brought together a group of 35 development practitioners from across the Hindu Kush Himalaya region, including participants from Nepal, Bangladesh, Bhutan, India, and Pakistan. The focus was on how to use foresight to help tackle the big regional issues of climate adaptation, creating diversified and resilient livelihoods in mountain areas, migration, and disaster preparedness.

ICIMOD invited Foresight4Food to collaborate in facilitating the training, using Foresight4Food’s Framework of foresight for systems change following the organization’s participation in a similar leaders capacity development workshop held in Africa in 2023 (see report and video here) and Foresight4Food’s 4th Global Meeting in Bangladesh.

The Nepal event was a good chance to build on Foresight4Food’s capacity development experience in Kenya, Jordan, Bangladesh, and Uganda. These are focus countries for the Foresight for Food Systems Transformation (FoSTr) programme, supported by the International Fund for Agricultural Development with funding from the Dutch Government.

While food issues were only part of the focus of the workshop, the issues raised during the week yet again highlighted that the way food is consumed and produced is central to all development issues. Migration, climate adaptation, equitable livelihoods and managing disasters are all interconnected with agrifood systems.

What was covered in the training workshop?

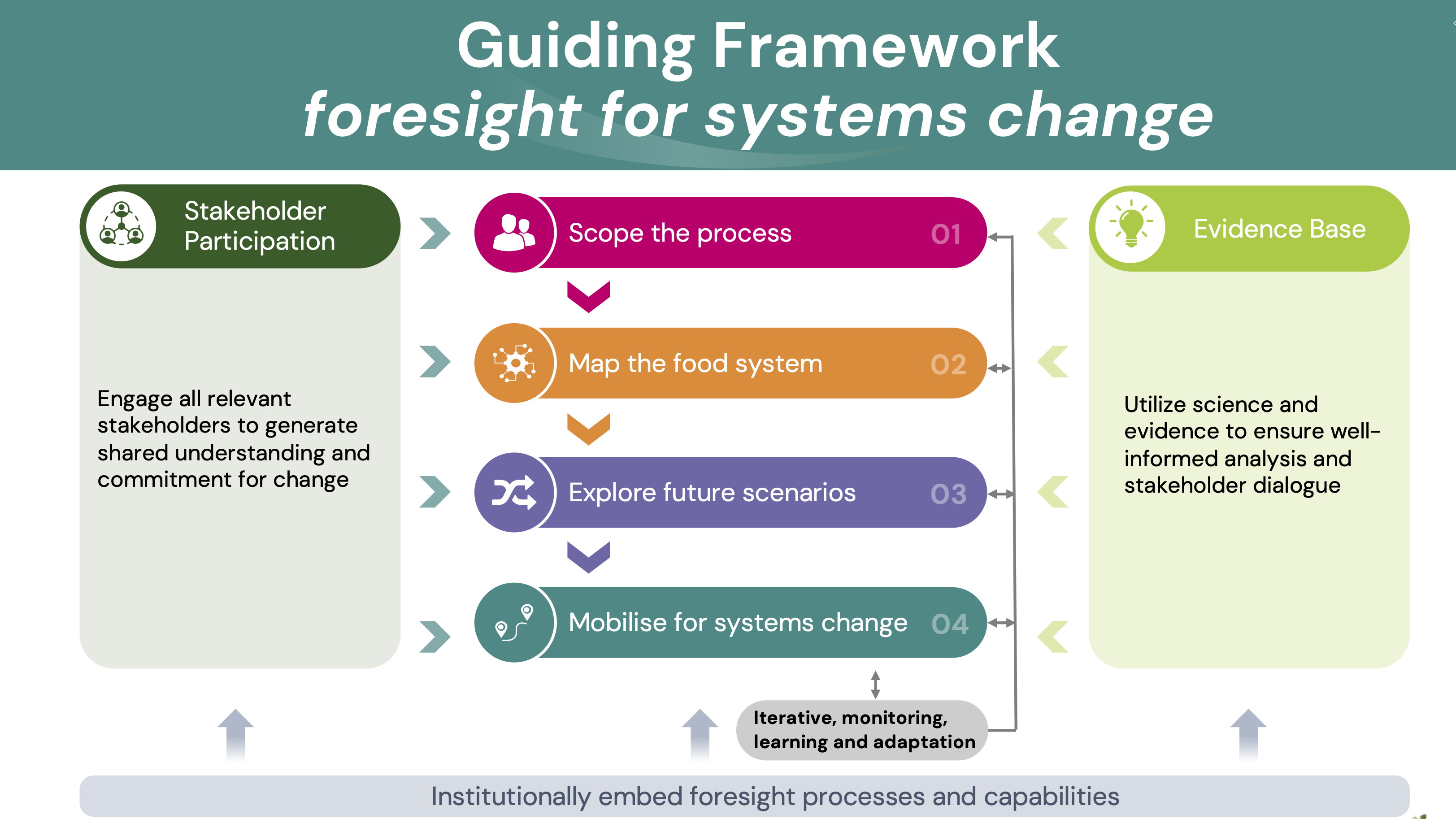

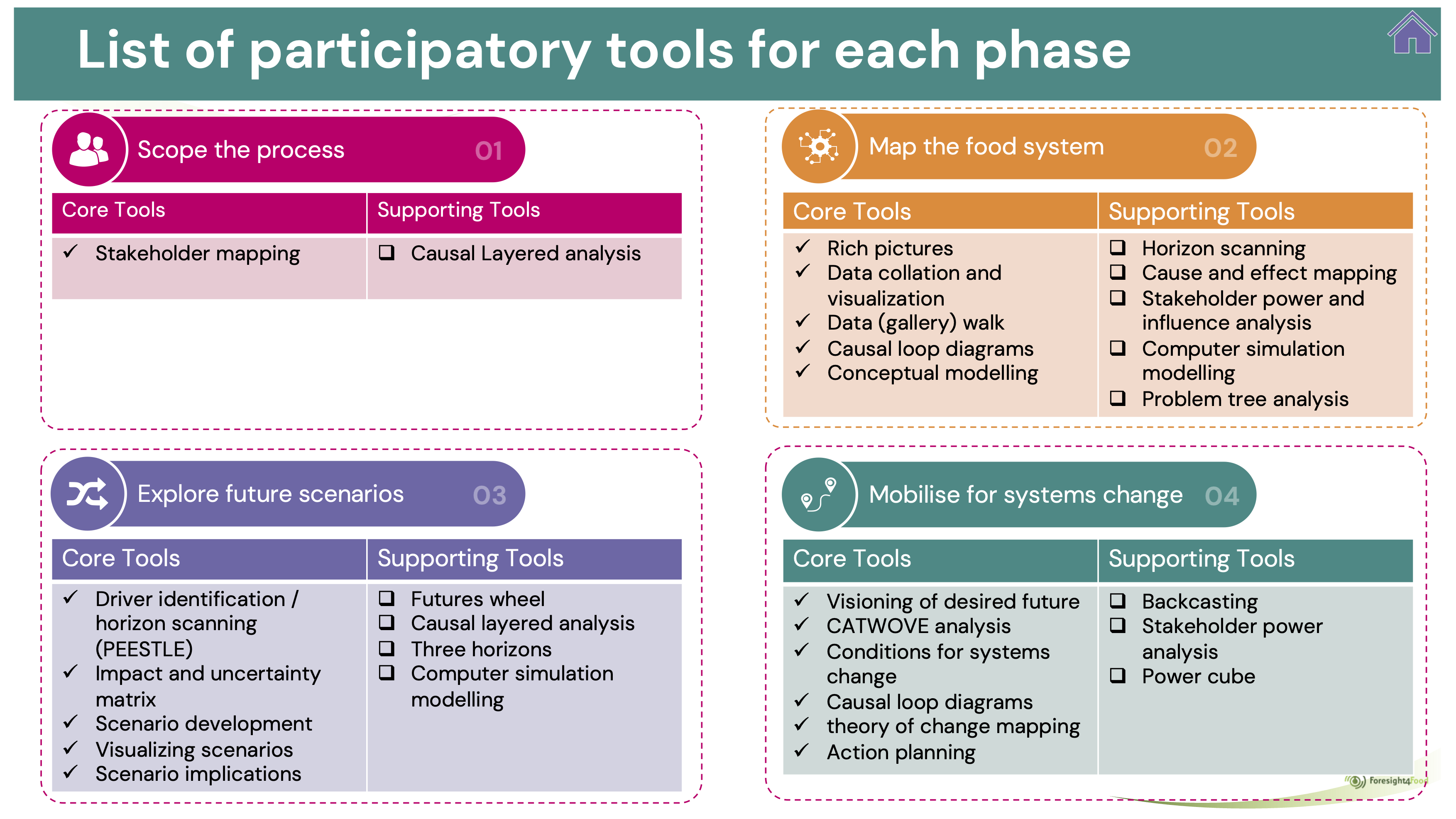

During the week, the participants worked through the four main phases of the Foresight4Food Framework:

- Scoping the process

- Mapping the system

- Exploring future scenarios

- Mobilising for systems change

For each phase, participants were introduced to background concepts and theory, and relevant participatory foresight and systems thinking tools. Rich pictures, drawn by participants to illustrate the whole system, is always a favourite. Other tools we worked with included horizon scanning of future trends and uncertainties (guided by the PEESTLE acronym), data exploration, causal loop diagrams, scenario development, visioning, back casting and conceptual modelling of systems.

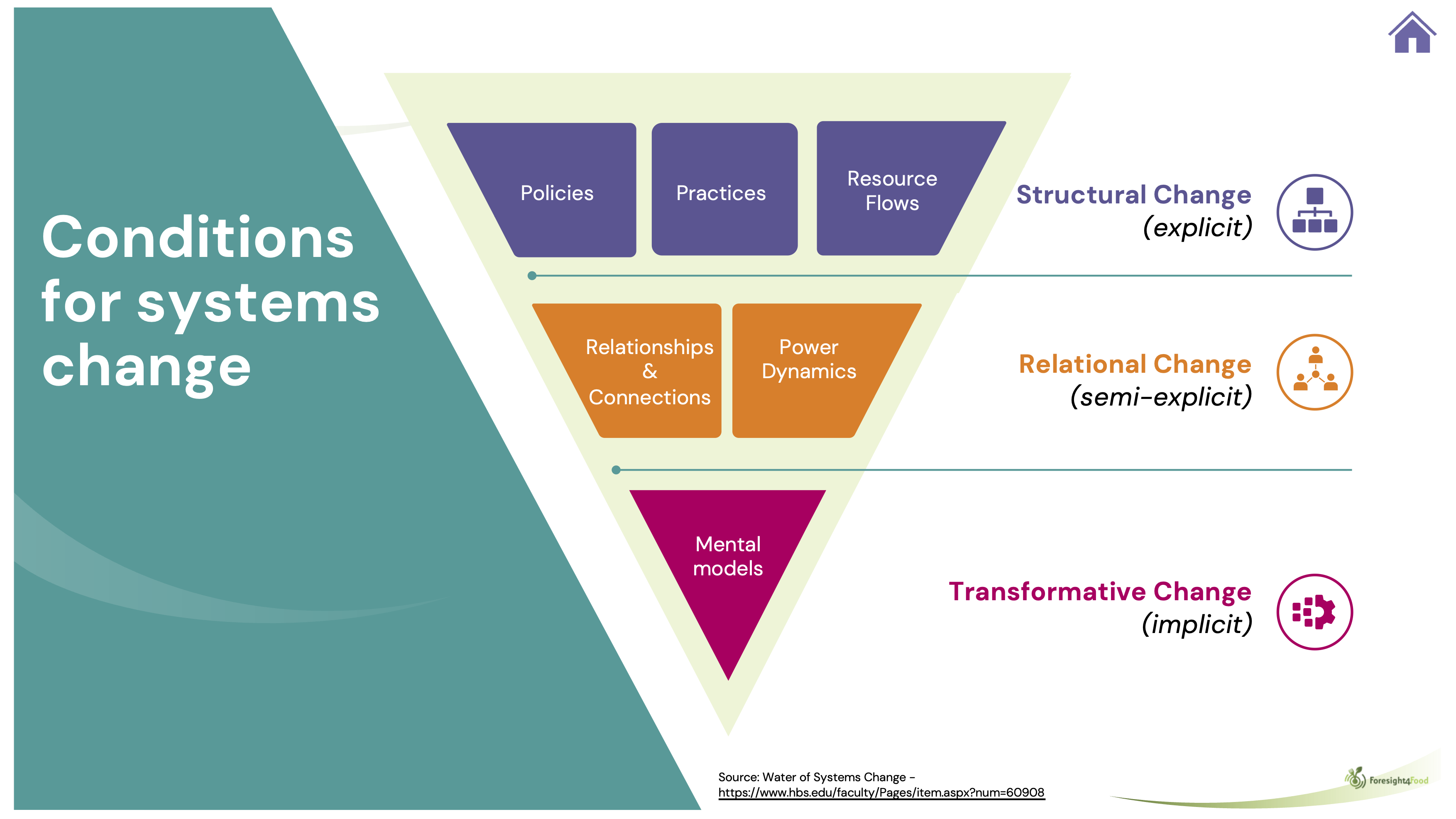

We discussed how change happens in complex adaptive (human) systems. The systems change “triangle” helped thinking about the role that mindsets and different forms of social and political power play in enabling or constraining change. The importance of bringing a gender equity and social inclusion (GESI) perspective to foresight was highlighted.

Participants applied their learning directly to the issues of climate adaptation, pastoralism, migration, and disaster preparedness.

The need for foresight

The global polycrisis is having a big impact on the Himalayas. The confluence of climate change, conflict, disease risk, inequality, biodiversity loss and geopolitical instability are bringing high levels of uncertainty and turbulence for citizens, businesses and governments across the region. For example, the melting of glaciers and the impact of extreme rainfall has profound implications for life in the mountains as well as for the billions of people who depend on the river systems that flow out of the Himalayas.

The Himalayas sit in the middle of a region with significant political tensions and shifting powers, which has major implications for the collaborative governance needed to effectively respond.

Foresight for systems change can help communities, organisations and governments better anticipate future risks and reimagine the future, so as to be more adaptive and resilient.

Thinking ‘out of the box’ – Foresight or “shortsight”?

Challenging discussions emerged during the week about how to ensure that foresight processes don’t just end up with the same old stuff – “old wine in new bottles”. To avoid this, we explored the need for “out of the box” thinking. This means looking for weak signals that might indicate a coming disruption, challenging assumptions about the future, bringing different perspectives to the table, using creative techniques to imagine radically different futures, and using the insights of “futurists”. A comprehensive horizon scanning process that explores mega-trends, trends, weak signals, critical uncertainties and wildcards helps to ensure foresight rather than “shortsight”.

Beyond tokenistic stakeholder participation

Across the Himalayas, it is local communities, local government and local businesses who must cope with the direct impact of floods, extreme heat, price fluctuations or disease outbreaks. Time and again participants returned to the importance of engaging local stakeholders to understand the challenges, and to generate pathways for greater resilience.

The discussion led to a shared understanding that this kind of participation from stakeholders requires genuine and open dialogue, made possible by using participatory workshop tools and techniques. However, all too often stakeholder engagement processes, when they do happen, fall back to formalised meeting structures, with speeches and presentations by “important” people, with little or no use of the sort of participatory analysis and dialogues tools participants engaged in during the training week. Advocating for effective, participatory and transformative stakeholder engagement processes is an obvious role for ICIMOD.

Institutional barriers to foresight and systemic practice

At the end of the week participants explored how to use foresight and systems thinking and practice in their own working context. Then some of the realities hit home.

Funders and donors often still force very linear, short-term and inflexible modes of programme design and management. Policymakers struggle to work effectively in a cross-ministerial way. People who see themselves as “senior” resist rolling up their sleeves and actively engaging in participatory processes with other stakeholders. Response strategies often stick to the safe space of technical analysis and technical solutions ignoring how mindsets and power structures block transformational change.

These are challenges that organisations like ICIMOD and initiatives like Foresight4Food need to help tackle if foresight is to have a real impact on policy and local action.

Cultivating a cadre of foresight and systems change practitioners

Participants recognised there is a limited number of practitioners/professionals across the region who have the knowledge, skills and experience to effectively design and facilitate foresight and systems change processes. A big effort is needed to create a cadre of practitioners who do have these capabilities.

To tackle this gap, governments can develop foresight units, universities could make futures literacy and systems thinking part of their curriculum, and development organisations need to in invest more in such human capabilities.

Way forward

On the last day of the workshop, the “collective intelligence” of participants was used to start framing a new horizon scan for the region that could follow up on the highly influential 2019 HIMAP report on the region.

Participants left with many practical ideas of how they could apply the foresight thinking and tools directly to their work.

For ICIMOD and Foresight4Food hopefully, this was just the start of collaborating to strengthen regional capacities for foresight.

The energy and commitment of participants were astounding, especially given long days of challenging discussions.

All in all, it was a super inspiring week – giving hope that with committed people like those in the workshop, supported by organisations like ICIMOD, we can together create a more resilient and equitable future.

by Bram Peters

As a part of the FoSTr programme, the Foresight4Food team organized the “Exploring Alternative Futures for Jordan’s Food System” workshop in Amman, Jordan that brought together food systems stakeholders in Amman to discuss the future of Jordan’s food security. Here are some of the observations and insights from the event.

With themes of resilience, adaptation, action, and collaboration, participants engaged in scenario planning and back-casting exercises to anticipate challenges and shape future outcomes. Key uncertainties like water availability, healthy diets, regional trade, and business structures were explored through four scenarios set in 2040. These insights, supported by quantitative modeling, fostered rich discussions about desirable futures and the actions needed today to create a sustainable, resilient food system for Jordan.

During the workshop, colleagues from the University of Jordan and Jordan University of Science and Technology presented four policy briefs. These were: Food Loss and Waste, Water-to-Food Conversion, State of Smallholder Farming in Jordan and Malnutrition. Each policy brief captures the state of knowledge and offers recommendations to explore how to address these issues from a food systems perspective.

The FoSTr team introduced four critical uncertainties that will be highly important and uncertain to the long-term future of the Jordan food system:

- The extent of fresh water available to agriculture

- The extent to which healthy diets are adopted

- Level of ease of regional trade

- The type of business structure the food system will have

Each of these uncertainties was combined to offer four scenarios, taking place in 2040, up for discussion with the participants. Supported by insights from quantitative simulation modelling, the implications on food systems outcomes were explored in each scenario. Some scenarios described that the people of Jordan adopt healthy diets despite a challenging regional trade situation. In others, severe limitations on fresh water for agriculture were seen in combination with a highly corporate-led food system.

Additionally, the participants explored how that situation might look in each. These scenarios served to open up minds towards the possibility of different situations emerging in the future and highlight the need for anticipatory action and systemic change.

The scenarios led to a discussion of what might be the ‘most likely‘ and ‘most desirable’ scenarios for the Jordan food systems stakeholders. The outline of a desirable future, informed by trends and uncertainties, was formulated to serve as a guiding star. A back-casting approach was used to then explore what events and turning points might occur between 2040 and now to realise that desired future. Based on this timeline, stakeholders brainstormed a range of different actions and stakeholders which are needed now, to already start pushing the system towards the Desired Future.

Building on the encouraging shared co-ownership of the results of the workshop, the Foresight4Food FoSTr team will continue efforts to develop policy briefs, deepen the action areas that were developed, and support the Food Security Council of Jordan in proving the underpinnings for the ongoing work on national food systems transformation.

Reflections on the Third Global Foresight4Food Workshop in Montpellier 2023

By Bram Peters, Food Systems Programme Facilitator

Strike? What strike?

Amid the turbulence created by strikes in France, a diverse and committed group of people still managed to get to and from the Third Global Foresight4Food Workshop in Montpellier from 7-9 March.

Perhaps, as foresight practitioners, we should have seen it coming! You would think that foresight practitioners who make it their business to look into the future might be better at anticipating turbulence, or at least a substantial level of social upheaval.

Why go through the trouble to come anyway? Because food systems are in turbulence as well. Never has there been a more urgent need to transform food systems. More than 3.1 billion people globally do not have access to healthy diets. The impact of climate change in the form of droughts and disasters is increasing. Agri-food systems are responsible for one-third of greenhouse gas emissions. The Covid-19 pandemic and the Russia war in Ukraine have shown how integrated, yet fragile, the global food system is.

We need foresight in food systems transformation

Yet, “the greatest danger in times of turbulence is not the turbulence; it is to act with yesterday’s logic” (according to futurist Peter Drucker). That’s where foresight comes in.

We need a long-term perspective to explore alternative pathways to reach desirable or avoid undesirable food system changes.

Following from the UN Food Systems Summit in 2021, many countries are searching for ways to navigate change and develop anticipatory policy to guide them.

As such, the issue on the table was: how can the foresight community of practice offer support and relevant advice to food system stakeholders?

Creating a safe space to think, connect and engage

In Montpellier, Foresight4Food brought together a diverse group of foresight practitioners, researchers, users of foresight and implementors of food systems approaches to discuss how foresight can contribute to national level food systems transformation pathways amid all this turbulence.

The Masterclass on the 7th generated a lot of energy, a shared language, and many practical explorations of tools and methods. The main Workshop on the 8th and 9th saw interactive exchanges, presentations of valuable projects and sharing of insights.

Among others, organisations such as FAO, CGIAR, GFAR and CIRAD shared ground-breaking applications of foresight thinking linked to food systems. There were cases from Asia, Africa; thematic cases on food systems data; new and past initiatives; dashboards and multi-stakeholder processes.

Researchers and data experts, such as from Wageningen University and Food and Land Use Coalition, shared innovative tools and models to advance new ways of projecting trends.

Critical perspectives were shared. Insights were brought from Africa and Asia, such as by Forum for Agricultural Research in Africa, and much more.

Moving the needle: developing our forward agenda

We, as Foresight4Food team, gained a lot of energy and motivation to continue fostering this vibrant network.

A few pickings of things we want explore moving forward. Develop and encourage ‘Communities of Practices’ through active partnership principles. Make a meta-analysis of existing food system foresight cases and comparative insights and lessons. Create guidance for foresight community on the process of actually doing foresight for food systems. Develop key principles for quality approaches and a toolbox to support implementation.

Thankfully, even in the face of the French strikes, a quality characteristic among foresight practitioners is the ability to be adaptable and flexible – as is needed when you work with the complexity of food systems.