By Herman Brouwer, WUR lead for FoSTr and Wangeci Gitata-Kiriga, FoSTr Country Facilitator Kenya

How can foresight transform the lives of pastoralists, fishers, and farmers in Marsabit County, Kenya? Marsabit County faces formidable challenges, with the escalating impacts of climate change threatening its food systems and livelihoods. Despite decades of significant support from development partners and government initiatives, the tangible results remain limited. This begs the critical question, inspired by David Peter Stroh: Why, despite our collective best efforts, have we struggled to foster lasting, positive change in Marsabit’s food systems?

Foresight could hold the key. By enabling stakeholders to anticipate future challenges, identify sustainable solutions, and adapt to evolving realities, foresight offers a transformative approach to addressing the county’s persistent issues. It’s time to rethink strategies and align efforts to create meaningful, long-term change for Marsabit’s pastoralists, fisherfolk, and farmers.

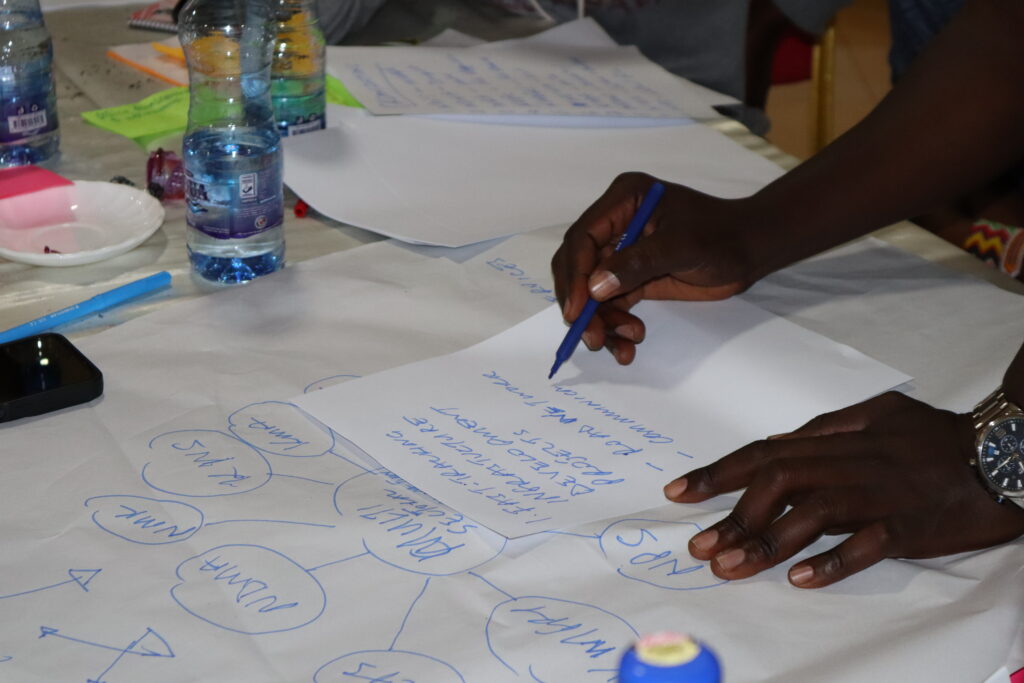

We brought stakeholders together in December 2024 to explore the above question, and to make a start to imagine different futures for the food system in Marsabit. Naturally, this involved a highly interactive discussion on the current food system and how we got to this situation – using a data walk with up-to-date data and analysis, as well as system maps. This provided the basis to jointly understand the dynamics of how food systems change (or resist change) and imagine how the food system could change even further in the next 10-15 years. The stories that participants came up with, based on their lived experiences in four distinct sub-counties of Marsabit, evolved into four scenarios. We used one of these scenarios (the ‘ideal one’ called Ajako, meaning ‘paradise’ in the Borana language) to create a vision for the future. We then identified the initial pathways and building blocks required to work towards this Ajako scenario.

Photo credit: Crispaus Onkoba/SID, used with permission

That’s the summary of where we ended up. However, an essential detail was omitted earlier: How do you ensure the right individuals and institutions are in the room? Achieving this required a carefully planned stakeholder engagement process, which began several weeks before the workshop. The process involved numerous meetings with individual stakeholders across the county to understand who was doing what, who was most invested, what had been successful, and what hadn’t worked in the past. The ultimate goal was to mobilize the most relevant and diverse stakeholders for the 3-day workshop.

We started by engaging the county leadership, relevant government departments, and development partners. But stakeholder mobilization didn’t stop there. We actively sought out voices often overlooked in food systems discussions: faith-based organizations, community groups, and private sector representatives.

Following the workshop, we ensured the initial excitement and momentum were sustained by maintaining contact with key participants. This effort culminated in the formation of a County Development Group, coordinated by the county government. This group brings together all actors actively engaged in food security initiatives, creating a collaborative platform for sustained impact.

Photo credit: Crispaus Onkoba/SID, used with permission

We argue that the investment in stakeholder engagement has been the most valuable ingredient of the foresight process so far. It has allowed our Kenya foresight team to obtain the right endorsements and buy-in at the right levels. Without getting the engagement process right, all participatory foresight tools, and supportive analytics, are at risk of falling flat.

There is a case to be made to only report on foresight processes after they are concluded, rather than at the start. This blog is an exception, to make the point that how you start matters.

The FoSTr Kenya foresight team, consisting of Results for Africa Initiative (RAI); Society for International Development (SID); International Livestock Research Institute (ILRI); University of Nairobi; Food and Land Use Coalition (FOLU); Wageningen University & Research (WUR); and the University of Oxford, will continue to support the County Development Group in Marsabit to coordinate actions of state and non-state actors towards achieving Ajako by 2040. A similar process is taking place in Nakuru County. Both have active linkages to Kenya’s national food system science-policy interfaces.

By Bram Peters – Food Systems Programme Facilitator, Foresight4Food

In the north of Kenya, on the border with Ethiopia, the landscape is expansive and dry. Pastoralism is the main source of livelihood, but to the west of this landscape is Lake Turkana, one of the largest saline desert lakes of the world. Here communities engage, some productively and others reluctantly and out of desperation, in fishing.

In March 2024, the Foresight4Food FoSTr team traveled to the fascinating Kenyan county of Marsabit to facilitate a multi-stakeholder forum to support the co-creation of the new ‘Sustainably Unlocking the Economic Potential of Lake Turkana’ programme.

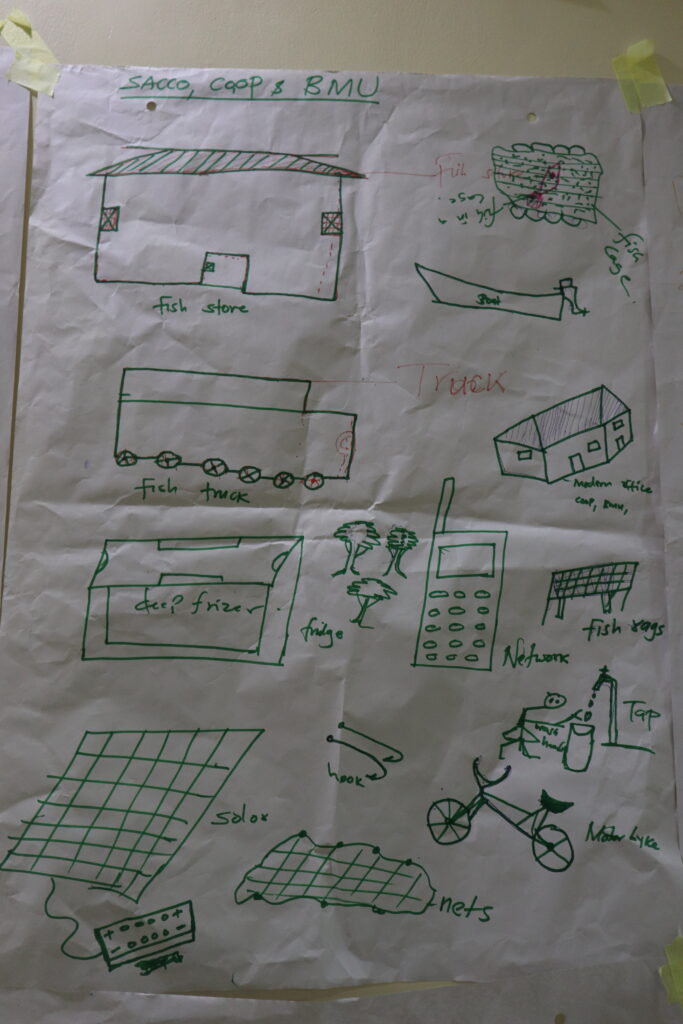

In Marsabit, stakeholders from around the Turkana Lake, including fishers, traders, service providers, county government technical officers, and non-governmental organizations, came together to analyze the context and co-create future scenarios and intervention areas for a new WFP and UNESCO programme, funded by the Embassy of the Kingdom of the Netherlands.

Together with the World Food Programme and the World Food Programme Innovation team, the FoSTr team held a highly interactive and productive three-day workshop. As most stakeholders mainly spoke Kiswahili, we switched to short presentations with much emphasis on interactive group work. On the first day, the workshop focused on contextual understanding of the Lake Turkana food system as well as the Marsabit county livelihoods, using the Rich Picture mapping exercise. Participants together drew the food system, the geography of the lake, but also the stakeholders, activities, key relations and dynamics.

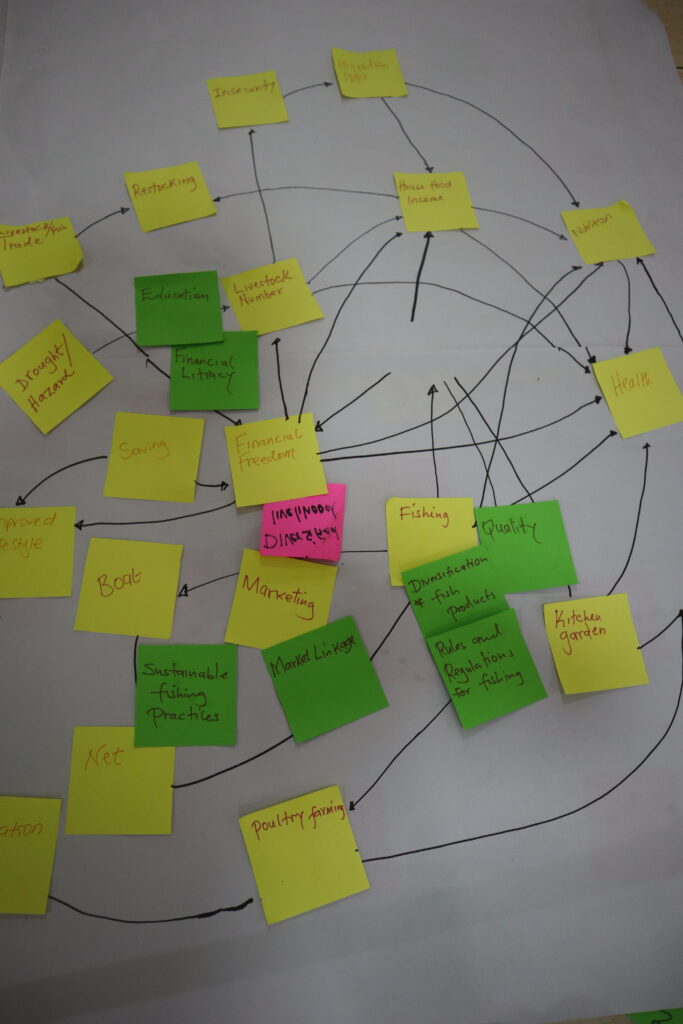

On the second day, the groups presented their deep knowledge of the context to each other and elaborated on this. Workshop participants tackled key trends shaping the food and livelihoods system: groups discussed how various themes (for example: lake water levels, fish stocks to income sources, conflict, and education) changed over time and what they expect to happen 10 years into the future. Important in this discussion is their analysis of what driving issues would influence change in the future.

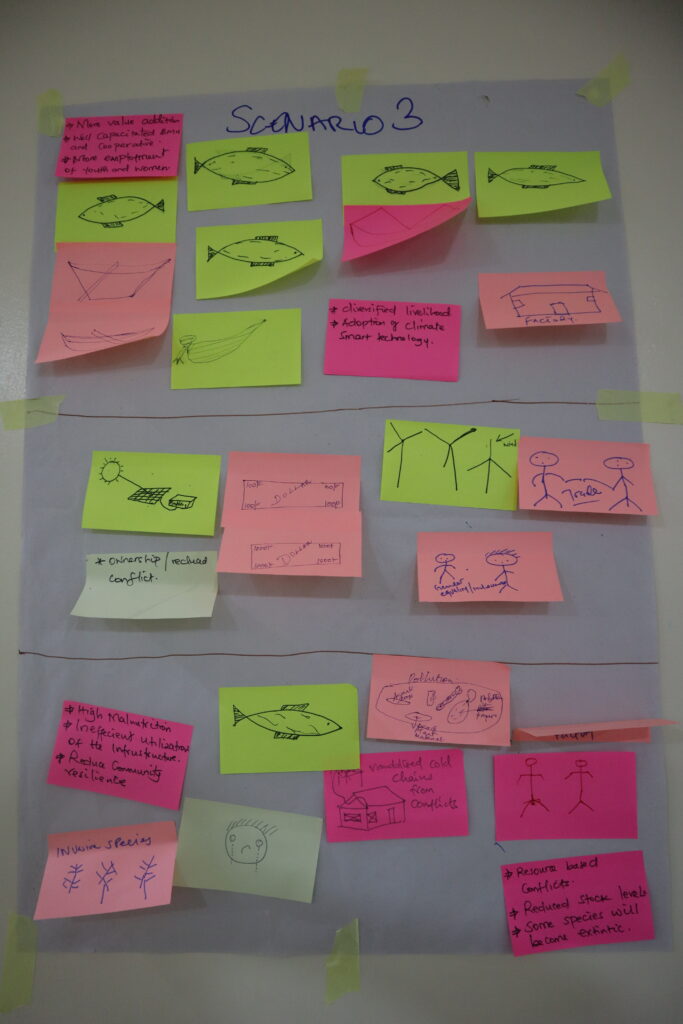

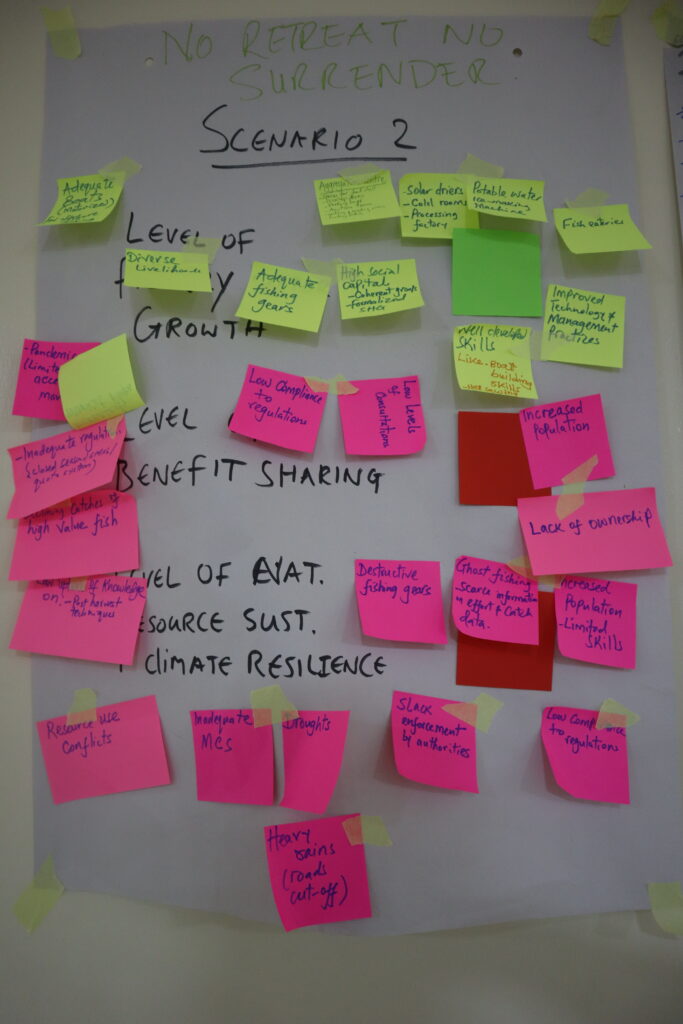

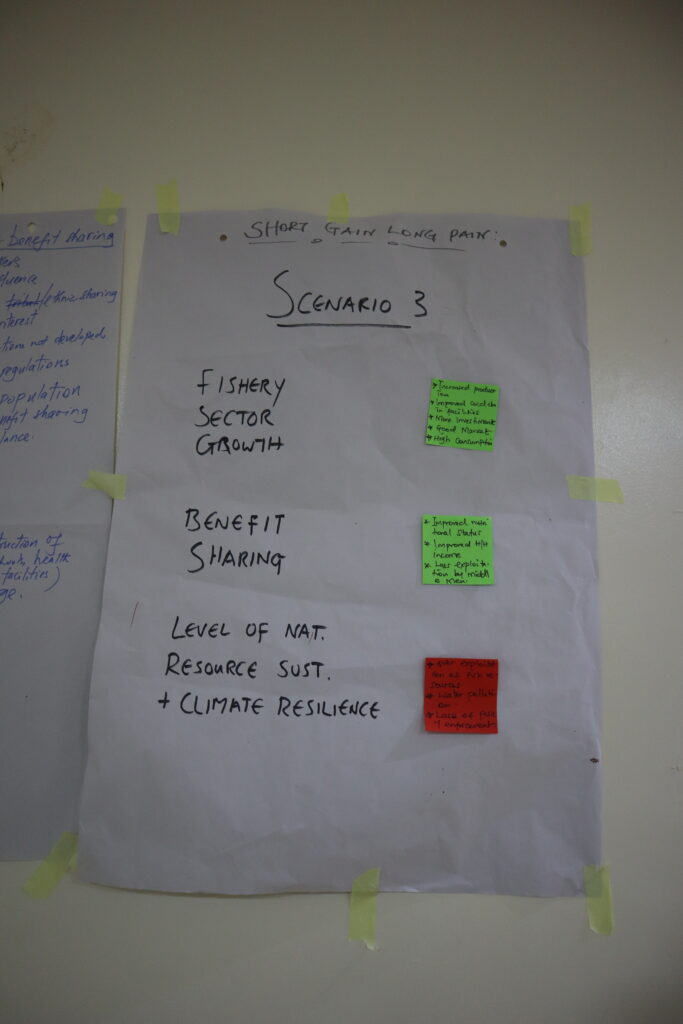

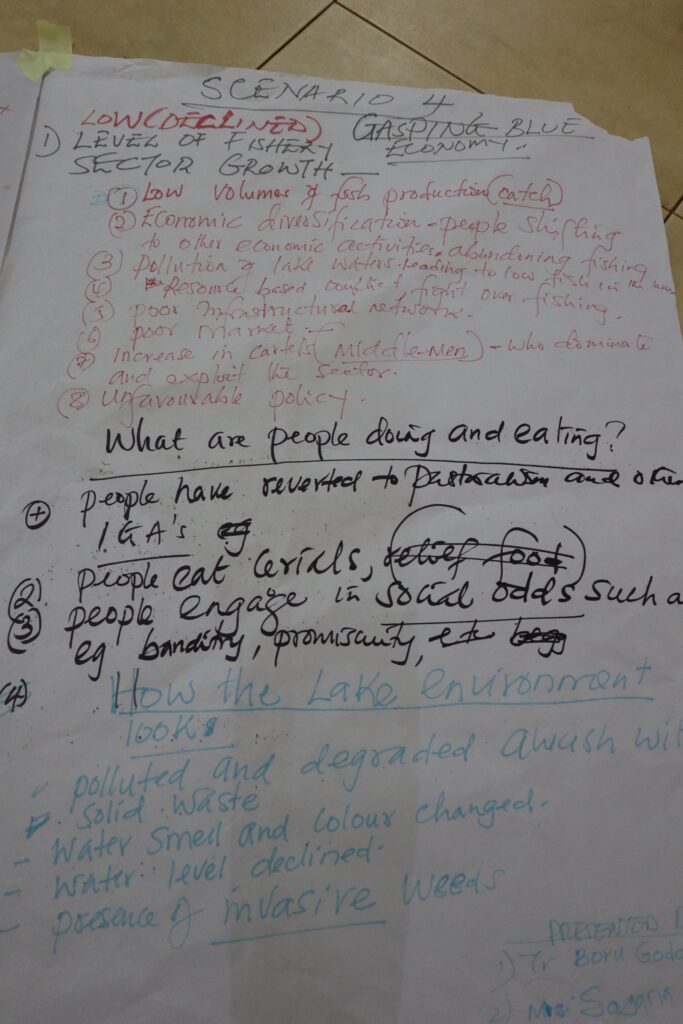

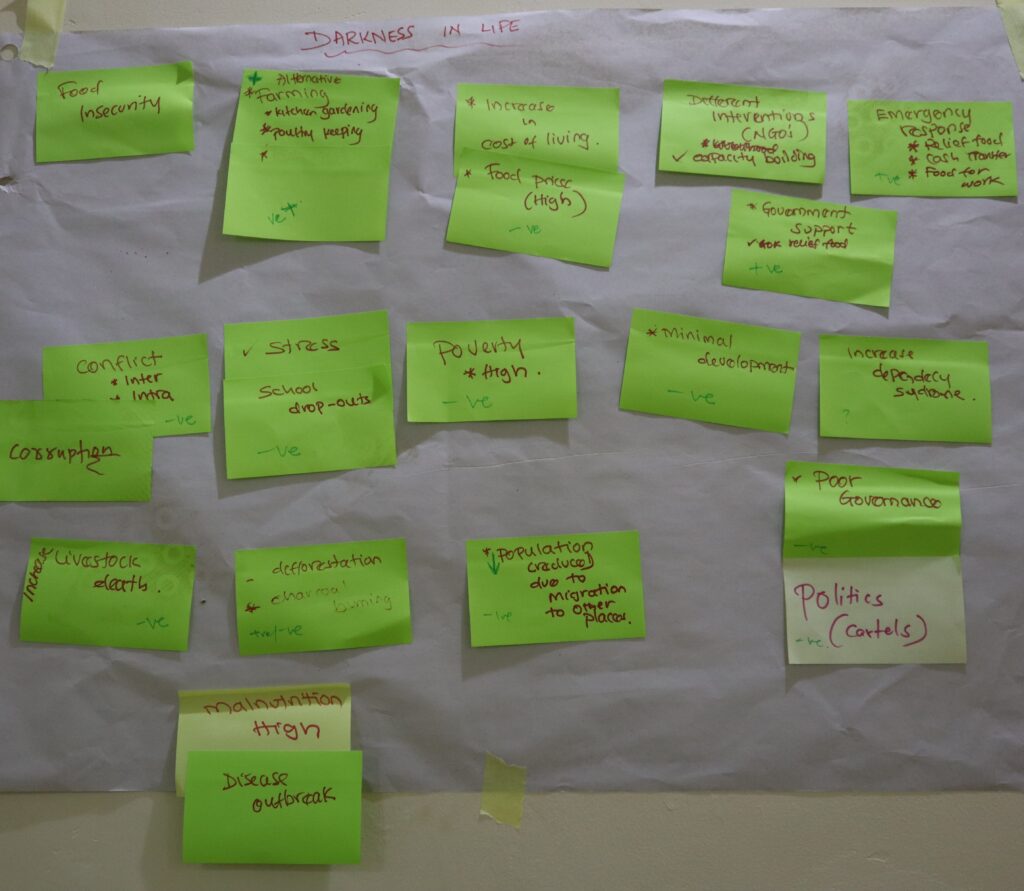

5 scenarios were created for the future regarding the fisheries sector and supporting livelihoods, as well as an in-depth discussion on key entry points for intervention in the system. These scenarios had names that described these futures succinctly:

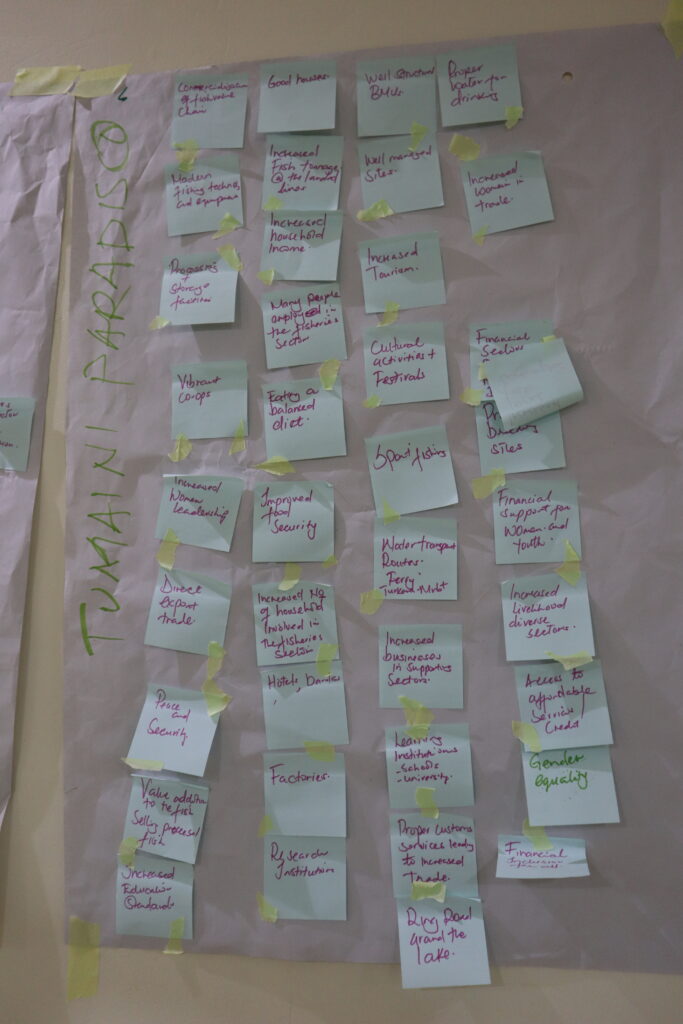

- ‘Tumaini Paradiso’, a future with a growing fishing sector, inclusive benefit sharing and sustainable natural resource management;

- ‘No retreat, no surrender’, a situation in which the benefits of a growing fisheries sector are controlled by a few;

- ‘Short gain, long pain’, a scenario where the fisheries sector grows and livelihoods improve around the lake, but the environment is not maintained;

- ‘Gasping blue economy but others rise’, is a future where the fisheries sector remains marginal for communities, but other sectors are developed that also contribute to inclusive development and environmental sustainability

- ‘Darkness in life’, a bleak outlook where none of the envisioned sustainable economic development around the lake delivers and where climate resilience is low, and conflict is rife.

Different stakeholders participating in the workshop had different opinions on the likelihood of certain scenarios emerging. Some imagined the situation worsening, while a few viewed the future more positively. These reflections clearly showed a combination of outlook of participants as well as the signals they interpret from the current situation and the trends seen now. Interestingly, none of the stakeholders felt the ‘Paradiso’ scenario was likely, showing that the programme needs to be modest in its systemic ambitions, but also be ready to do things very differently. These scenarios showed what could become a very relevant frame of reference to the stakeholders as well as the programme implementors.

On the last day of the workshop, participants explored a common vision for the future, and how the food system is currently working. This led stakeholders to have a first try at exploring what is needed to change that system toward the common vision.

At the end of the workshop, I felt highly positive about these fruitful discussions that enabled participants to think about what might happen to the Marsabit food system in the years to come, and what factors would influence these changes. In addition to that, the insights gathered through the multi-stakeholder forum are expected to not only support the inception phase of the programme but will also support multi-stakeholder engagement throughout the programme.

The Foresight4Food FoSTr team will continue to support the World Food Programme team in realizing the ‘Sustainably Unlocking the Economic Potential of Lake Turkana’ programme inception phase. A follow-up workshop will take place in Turkana County from March 25 to 28, with stakeholders from that side of Lake Turkana.