By Jim Woodhill, Lead Foresight4Food Initiative

How can we understand the multiple dimensions of transforming food systems? On top of the disruptions to peoples’ incomes and food supply chains caused by COVID, the Russia war in Ukraine has pushed fertilizer, energy and food prices to all-time highs. Millions are falling back into hunger and poverty. Even in the affluent world, many poorer people in society are being forced to use food banks, eat lower nutritional value food, and make tough decisions between using their dwindling financial resources to pay for food or keep their houses warm in winter.

This situation underscores the conclusions of the UN Secretary General’s 2021 Food Systems Summit that highlighted the need for a far more resilient, equitable and sustainable food system. Heads of state universally declared that a transformation of food systems is needed to cope with climate change, tackle hunger and poor nutrition, reduce poverty, and protect the environment.

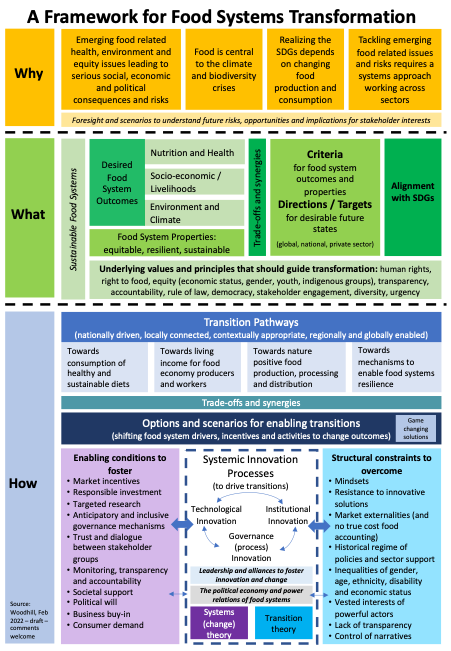

But what does food system transformation actually mean? In this blog, I outline a framework (Figure 1 below) for thinking about food systems transformation. It is based on WHY change is needed, WHAT needs to change, and HOW change can be brought about.

Introducing food systems transformation

“Food systems” has provided a new framing for a more integrated approach to the issues of food security and nutrition, agriculture, climate change, environment and rural poverty. This systems view makes a lot of sense as, one way or another, how we consume and produce food is central to all the Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs). Billions of people work in the agri-food sectors, everyone needs a healthy diet, food is central to culture, food trading and retailing are huge markets and agriculture is the biggest user of land and water resources.

This systems perspective is bringing together a plethora of associated ideas, language and concepts. Terms such as food system outcomes, transformation, transition pathways, resilience, equity, trade-offs and synergies, living income, nature positive approaches, agroecology and the true-cost of food are just a few of these. The emerging food systems discourse is also giving more attention to power structures, the political economy, stakeholder engagement and dialogue, empowering excluded voices, market externalities, coalitions, economic incentives, and data needs.

Before explaining the framework, let’s ask what is meant by a transformation of food systems. Transformation means a complete or radical change of something in form, function or appearance. So, transforming food systems means fundamentally changing how they operate to dramatically improve environmental, health and livelihood outcomes for society at large. This requires fundamental changes in the behaviour of consumers, investors, agri-food sector firms, farmers, researchers and political leaders. In turn, a dramatic shift in economic and social incentive structures is needed, with the true cost of food embedded into how markets function. To avoid future risks these fundamental changes are needed with urgency.

To-date, and perhaps not surprisingly, much of the debate and political narrative has focused on what needs to change and why. The more difficult question of how change can actually be brought about has so far received less attention. Perhaps this is because such discussion cannot avoid difficult political-economic issues of long-term collective interests versus short-term vested interests. We are still a long way from having sufficiently detailed strategies, plans of action, policy commitments and investments to bring about the transformation. How to get from WHY to HOW?

WHY transform food systems?

Why food systems need to change has been well analysed, is clear to most stakeholder groups, and is increasingly articulated by political leaders. The problems and longer-term impacts and risks of the way food is currently consumed and produced is well-evidenced in terms of the negative consequences for health, the environment, and equitable economic development. If this interconnected set of issues is not tackled effectively and promptly the risks of dire longer-term social, economic and political consequences are high.

Food value chains contribute about a third of total greenhouse gas emissions. Agriculture and fishing are by far the largest causes of biodiversity loss and ecosystem degradation. These impacts on the environment cycle back to undermine the Earth’s very capacity to produce food for the long run.

Further, it is increasingly clear that the SDGs and in particular SDG1 – no poverty – and SDG2 – zero hunger – will not be achieved without a fundamental change in how food systems function.

The work of the Food Systems Summit brought a much wider understanding and acceptance that the numerous development issues linked to food can only be effectively dealt with through a cross-sectoral and systems-oriented approach. An additional critical aspect of the food systems framing is an acceptance that these issues are of equal importance for countries in the Global North and the Global South.

Foresight and scenario analysis can make a vital contribution in helping to explore the ways food systems might change and with what risks and opportunities for different stakeholder interests.

WHAT needs to be transformed?

The desired outcomes from food systems have become well-articulated in terms of three main areas:

- ensuring food security and optimal nutrition for all.

- meeting socio-economic goals, in particular reducing poverty and inequalities.

- enabling humanity’s food needs to be met within planetary environmental and climate boundaries.

Overall, food systems are recognized as needing to function with the properties of being resilient to shocks, sustainable over the long-term and equitable in terms of the costs and benefits to different groups in society.

Across these food system outcomes and properties, there are inevitable trade-offs and synergies, which bring with them the potential for both conflict and collaboration between different interest groups. While the broad directions for desired food system outcomes and properties are relatively well established, the nature and extent of these synergies and trade-offs is much less well understood. More work is also needed to establish specific criteria, directions for change and targets for food system outcomes, which will be necessary to guide transformation at national or local levels, within sectors or across business operations. More attention needs to be given to how the criteria and targets for food systems transformation align with those of the SDGs.

The Food Systems Summit and the work of the Committee on World Food Security (CFS), in particular its recently adopted Voluntary Guidelines of Food Systems and Nutrition (VGFSyN), have identified underlying values and principles that should guide the processes and outcomes of food systems transformation. These include human rights (incl. the right to adequate food), sustainability, resilience, transparency, accountability, adherence to the rule of law, stakeholder engagement, gender equality, and inclusivity (particularly for women, youth, indigenous groups and small-scale producers).

Food systems that deliver on the desired outcomes and properties, and function in adherence with the underlying values and principles articulated above, can be considered as sustainable food systems.

HOW can food systems be transformed?

The transformation of food systems will require a focus on transition pathways, largely driven at the national level but connected with local processes and enabled by larger-scale system shifts at regional and global scales. Four main transitions can be identified from the Food Systems Summit deliberations:

- a consumption shift to sustainable and healthy diets.

- an equitable economic shift to ensure food economy producers and workers, have a fair living income including being able to afford healthy diets.

- a shift toward nature positive approaches for food production, processing and distribution which have a net-zero climate impact and operate within a sustainable and safe zone of utilizing natural resources.

- a shift towards mechanisms of resilience for food systems which can ensure societies a large to not risk food insecurity and that groups who are poor or vulnerable are protected.

Desired food system outcomes can potentially be achieved through multiple different pathways and scenarios with numerous different trade-offs and synergies. For example, consumption shifts could be influenced by food prices and taxes, public education, product labelling or shifts in food marketing practices. Resource efficiency and circularity could be achieved by a number of measures, including consuming (at a global level) less animal protein, adopting agroecological approaches, energy efficiency, water management, reducing waste, or new technologies which reduce methane emissions from cattle farming. Equity for those working in the sector could be improved through various combinations of increasing food prices, implementation of labour and land tenure rights, improved social protection, improving overall rural economic development or creating greater economic opportunity outside the food sector.

Developing and assessing the options and scenarios to enable transitions is where a vast amount of investment and work is needed if food systems are to be sustainably transformed. The Food Systems Summit process identified a significant number of “game changing solutions”, ideas that could contribute to developing viable transition pathways. Further assessment and work will be needed to refine, prioritize and build on this contribution from the Summit.

Scenarios can help identify potential trade-offs and co-benefits of those solutions across intended food system outcomes. The principles of equity and inclusion are especially important to consider when analysing options and trade-offs. For example, gender equality is not guaranteed to improve with increased income from food systems activities, so attention must be paid to gender-transformative and inclusive value chain development.

Generating viable options for transforming food systems will require systemic innovation that connects processes of innovation across the domains of technology, institutions and social norms, and politics and governance. Food systems transformation will be impeded or enhanced depending on the constellation of power relations across societies and the agri-food sector. This is particularly salient where influential actors are prepared to defend vested interests at the cost of changes for the wider collective good. Such systemic innovation will require profound paradigm shifts and completely new approaches to policy coherence.

Insights from systems theory and transition theory have much to offer in terms of how to guide and broker change in complex (food) systems. For example, encouraging, supporting, linking and scaling up “niche” innovations that can respond to new needs, challenges and opportunities. This requires adaptation to local contexts that can be supported by territorial approaches to development. Over time, such innovations can help to disrupt existing and unsustainable food systems “regimes” (attitudes, policies, power relations, market relations) and enable more sustainable alternatives to become embedded.

The Food System Summit has helped to identify numerous factors that can be considered as enabling conditions or structural constraints for food systems transformation. Systems change involves “nudging” systems in desirable directions by working to amplify enabling conditions and dampening structural constraints. This requires attention to the underlying political economy. Strategic alliances and political leadership are needed to help shift understanding, narratives and power dynamics.