The global food system needs to be transformed. It needs to deliver better health and improved livelihoods while protecting the environment and minimizing negative social impacts.

However, there are many interconnected factors playing a role. Food Systems are complex adaptive systems which require a deep analysis of their various driving forces and dynamics. They are shaped by a multitude of interconnected factors or drivers, some well-defined, others with a lot of uncertainties with them. A recent study by Forsight4Food identified the most critical drivers of the global food system as described by a set of 19 recent foresight reports. It was not easy to define and categorize these very drivers, and we will also discuss these challenges in this blog.

The Entangled Web of Drivers

Many studies, from the 2003 Millennium Assessment report to FAO 2022 have defined what is a ‘driver’. But the challenge is the lack of a universally agreed-upon definition for a driver. This means that categorizing these drivers is problematic. For instance, they can be classified based on their relationship with other drivers (direct or indirect), external factors (like PESTLE analysis- Political, Economic, Sociological, Technological, Legal and Environmental), or the extent of our knowledge about them (known knowns or unknown unknown).

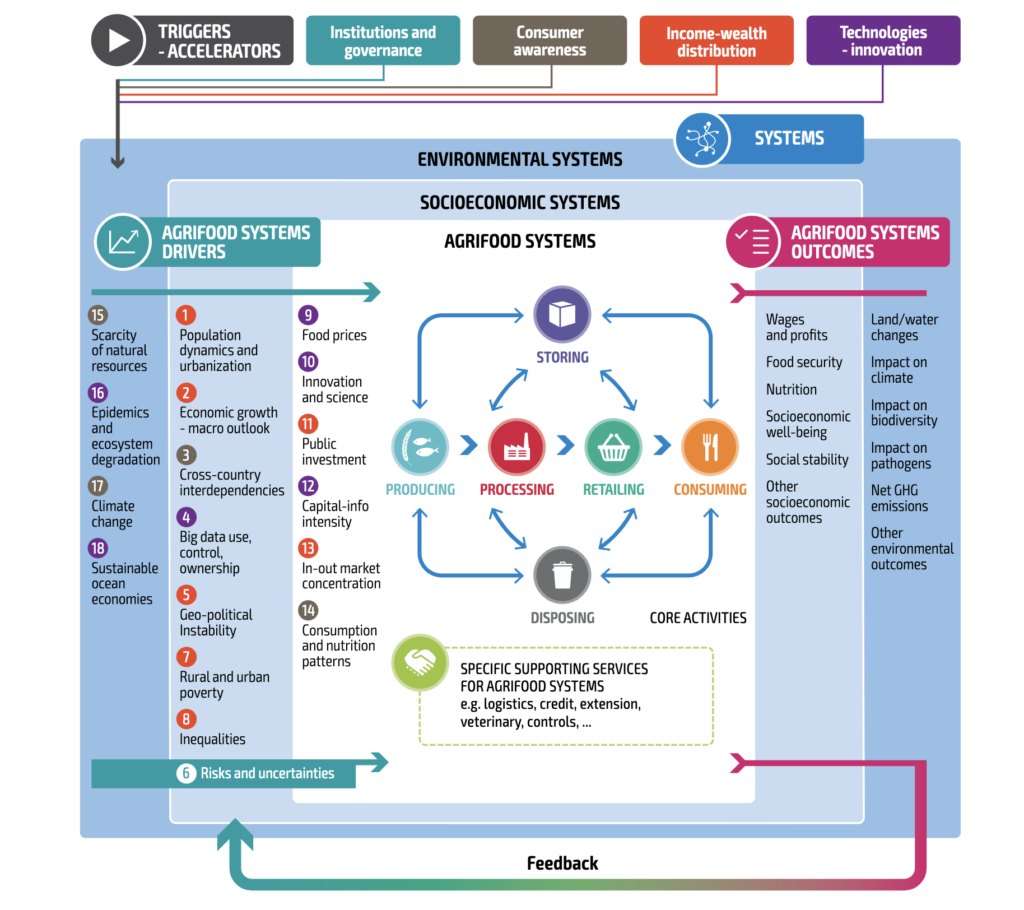

What makes it even more intricate is that, due to the systemic nature of the food system, its nutrition, environmental condition, and economic development outcomes feedback indirectly becomes driver themselves. This creates feedback loops that complicate pinpointing which drivers are truly direct and which are indirect. Ultimately, it depends on the specific part of the system you’re focusing on. This is nicely depicted in the FAO’s food system diagram, however, it does not show the interconnections between different factors which is what needs careful consideration.

Source: FAO 2022

Here’s another layer of complexity: There are “known knowns” drivers like climate change and population growth and many models have been developed to understand the future trend. Then there are drivers such as government interventions (trade policies and subsidies) which is undoubtedly an important driver, but predicting the future impact of specific interventions is challenging. Similarly, we understand that diets are shifting towards more protein, but whether this trend holds true depends on the specific scenario we’re considering. These are “known unknowns” – we know they exist, but their future impact is a mystery. But the complexity is even deeper: “unknown unknowns”. Take the influence of social media on food choices. This is a relatively new area of study, and its full impact on the food system remains unclear. There can be overlaps in any type of categorisation system. Therefore, it is important to involve experts at this stage.

Identifying the Critical Few

The next hurdle is identifying “critical drivers” – those with the most significant potential to impact the food system. These drivers can influence various stages through established historical trends or emerging uncertainties. A key challenge lies in determining their relative importance across diverse contexts, often depending on stakeholder perspectives. For instance, immigration policies can have a significant impact on agricultural workforces in some regions. Incorporating stakeholder consultations is crucial to prioritize the most impactful drivers in these specific contexts.

Keeping the Conversation Open

It’s vital to remember that the impacts of drivers manifest differently across various socio-economic settings and among different food systems stakeholders. Highlighting the context in which a driver is critical helps us develop more targeted solutions.

We must also acknowledge that new or emerging drivers with unclear trends can also have profound impacts. For example, as mentioned earlier, the role of social media in influencing food choices is a relatively new area of study.

Therefore, the conversation around identifying critical drivers needs to be open to periodic updates. As we uncover new information and witness the emergence of new drivers, we can refine our understanding of the food system and adapt our strategies accordingly.

Future Trends and Projections

The future trajectory of these drivers is influenced by various factors, both internal and external to the system. Climate change, consumer behaviour, and technological advancements all play a role in shaping the path ahead. These complexities of cross-impacts create uncertainties about the future, often interpreted through different assumptions in various projections.

Many reports from IPCC, FAO and UNDP present some of the trends and projected trends around food system drivers. But these vary due to the underlying assumptions. Moreover, deciphering these projections can be challenging due to two key factors: 1) varying timescales and 2) diverse representations of what a sustainable food system actually looks like. However, by delving deeper into these assumptions and comparing them, we can gain a more comprehensive understanding of the possible futures that lie ahead.

What we found…

The review of recent studies on food system drivers revealed a mix of established and emerging influences. We categorised drivers using the known-knowns and known-unknowns classification. Long-standing factors like demographic changes, climate issues, technological innovation, resource efficiency, socio-economic inequalities, government interventions, health considerations and level of connectivity continue to shape food systems, while new drivers such as the rise of e-commerce post-COVID-19, concerns about power imbalances in food value chains, labelling and packaging, data ownership issues, the role of indigenous knowledge, labour migration policies and perceptions around vegan and vegetarian diets are gaining importance. The relevance of these drivers varies based on stakeholder perceptions, indicating the diverse issues decision-makers must consider for effective management and adaptation.

The review also noted varying levels of uncertainty associated with these drivers. Established drivers, such as demographic trends, have narrower uncertainty ranges due to extensive research, leading to more consistent projections. However, differences in time frames, methods, and assumptions among studies complicate direct comparisons of quantitative trends. Emerging drivers, like government interventions and social media’s influence on consumer behaviour, exhibit broader uncertainty ranges and diverse trend directions, making them particularly significant for developing future scenarios. Our upcoming report will discuss these critical points in detail.

Conclusion

Transforming global food systems to deliver better outcomes is a complex and urgent challenge. Understanding the critical drivers shaping these systems, both well-known and emerging, is essential for creating the societal understanding and political will needed for meaningful change. Just as a map evolves with new discoveries, our understanding of these critical drivers needs constant refinement. Through ongoing research, collaboration, and open communication, we can navigate the complexities of the food system and support targeted solutions towards a more sustainable food system.

FAO’s new insightful scenarios for the future of food systems

By Bram Peters, Foresight4Food Global Facilitator

What drivers can trigger food systems transformation? How can we move beyond business as usual in the face of rising food insecurity, environmental degradation and economic instability? The good news is that we can shape food systems to be more resilient and sustainable. The challenge: trading off short-term benefits in search of longer-term outcomes. FAO developed four future scenarios that explore that explore these questions and how we can navigate such paths.

End of 2022, the United Nations Food and Agriculture Organisation (FAO) published the report ‘The Future of Food and Agriculture – Drivers and triggers for transformation’. The key triggers and drivers for transformation are identified based on a diverse and wide range of literature and expert knowledge and then applied to four scenarios to achieve the FAO goal of ‘Four Betters’: better production, better nutrition, better environment and better life. Trade-offs over time and the key use of policy triggers are at the centre of the report’s conclusions. This blog dives into these drivers and futures, and delves into the key implications of this report.

In Search of ‘Four Betters’

FAO strives for ‘Four Betters’: better production, better nutrition, better environment and better life. How to achieve such a vision, and how will this look in the future?Much depends on how drivers play out, how stakeholders tackle trade-offs, and how certain triggers are turned into policy options and implemented. The recent report makes clear that the historical development paths followed by high-income countries, drawing from hegemonic power, colonial wealth and unsustainable practices, are impossible for current low- and middle-income countries to follow. This requires a mindset shift regarding taking responsibility, sharing burdens and investing in a new type of focus on the long-term objective.

Difficult-to-navigate trade-offs and choices include:

- Short-term productivity gains against greater sustainability and reduced climate impact; “Better production starts from better, critical and informed consumption, but producing more with less will also be unavoidable”.

- Efficiency against inclusiveness; for instance, “technological innovations are part of the solution – provided new technologies and approaches are also accessible to the more vulnerable”.

- Short-term economic growth and well-being against greater long-term resilience and sustainability. In concrete terms, this means “selling the message that well-off people have to lose out economically in the short run, in order to reap environmental benefits and resilience for all in the medium and long term is counterintuitive in this short-termism era”.

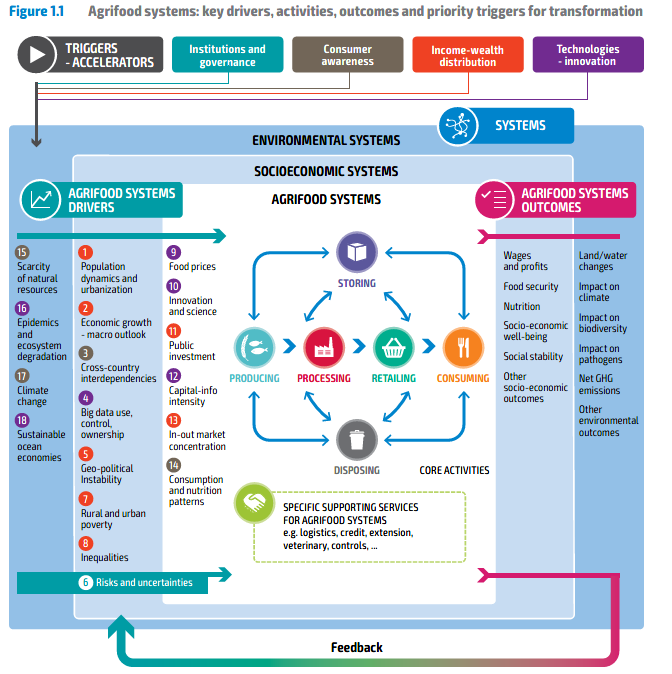

These are difficult but essential messages. The report highlights the importance of realising that food systems transformation is an inherently political and cultural process. Promising drivers and triggers for change are occurring globally, but must be harnessed and adapted. Let’s have a look at some of the drivers identified. Drivers are categorised as ‘overarching, systemic drivers’, which often include global, geopolitical and demographic elements, ‘drivers affecting food access and livelihoods’, and ‘drivers that affect food and agricultural production and distribution processes. Drivers within these categories affect agri-food, socioeconomic and environmental systems (Figure 1.1).

Captured in an agri-food system framework (partially based on previous work from Foresight4Food), some predominant drivers include scarcity of natural resources, epidemics and ecosystem degradation, cross-country interdependencies, inequalities, big data use and control, geopolitical instability, food prices, public investment and consumption and nutrition patterns. Cutting through these drivers are ‘risks and uncertainties’, as many drivers can turn into hazards, risks and cascading crises.

New Future Scenario Narratives

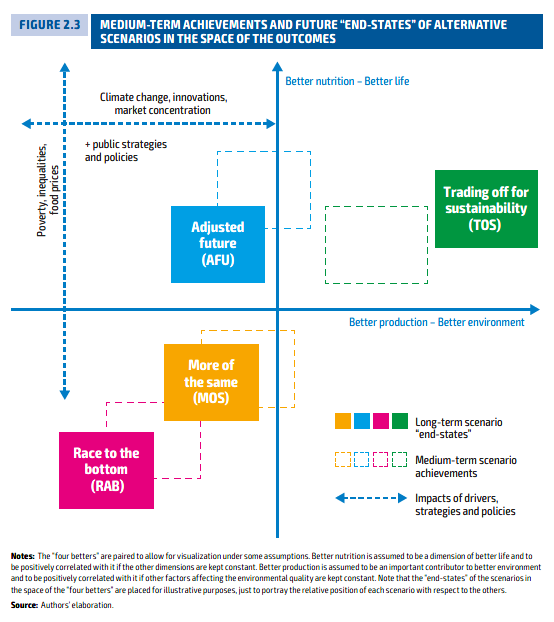

Radically divergent futures can emerge if the interactions of drivers, changes in individual and collective behaviour, the materialization of natural events, risks and uncertainties, and the influence of public strategies and policies play out differently. FAO developed four scenarios from the near future to the end of the century and explored the implications of each for food systems. The FAO ‘Four Betters’ were used to formulate four visions and narratives of the future. Using a ‘back-casting approach’ (where a number of aspirational visions are developed and it is then explored what future pathways could lead to these futures). The FAO team explored how each of these futures could be reached through combinations of key drivers, interconnections between agri-food, socioeconomic and environmental systems and ‘weak signals’ of possible futures.

By imagining alternative pathways and priority trigger points, the four scenarios are not defined as separate destinations to get to by moving along four different train tracks. Instead, each future

scenario could be reached at different points depending on the strategic policies and decisions implemented, the trade-offs in policymaking, and unless irreversible processes are triggered.

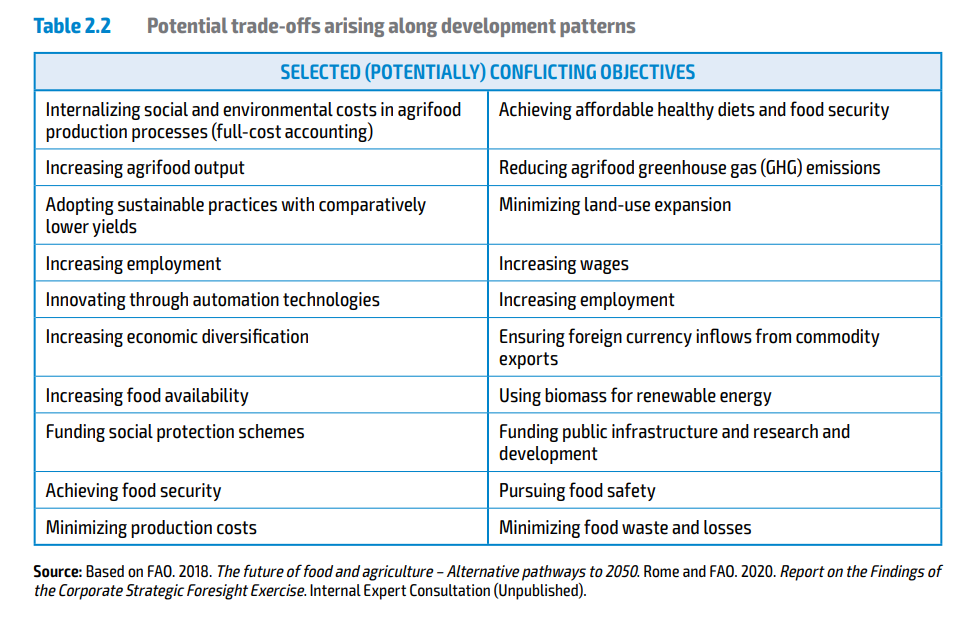

Trade-offs now and in the future will offer wicked dilemmas for decision-makers. Foresight thinking highlights that certain current decisions may lead to short term results but can increase medium and long-term uncertainty and, in the worst situations, foreclose certain long-term futures. See various conflicting policy objectives in Table 2.2.

The four scenarios are visualised on a juxtaposition of 2 paired FAO ‘Betters’: ‘Better nutrition/Better life’; and ‘Better production/Better environment’. These betters were paired to enable visualisation and relative positioning of futures vis-à-vis each other in a matrix.

The four scenarios include:

1. More of the Same (MOS)

2. Adjusted Future (AFU)

3. Race to the Bottom (RAB)

4. Trading off for Sustainability (TOS)

More of the Same involves muddling through reactions to events and crises while doing just enough to avoid systemic collapse, which will lead to the degradation of agri-food systems’ sustainability and to poor living conditions for many, increasing the long-run likelihood of systemic failures. Adjusted Future entails that some moves towards sustainable agri-food systems will be triggered in an attempt to achieve Agenda 2030 goals. Some improvements in terms of well-being will be obtained, but the lack of overall sustainability and systemic resilience will hamper their maintenance in the long run.

Race to the Bottom is characterised by gravely ill-incentivized decisions that will lead to the collapse of substantial parts of socioeconomic, environmental and agri-food systems, with costly and almost irreversible consequences for a vast number of people and ecosystems. Trading off for Sustainability would mean that awareness, education, social commitment, sense of responsibility, participation and critical thinking will trigger new power relationships and shift the development paradigm in most countries. Short-term gross domestic product (GDP) growth will be traded off for the inclusiveness, resilience and sustainability of agri-food, socioeconomic and environmental systems.

Each scenario narrative explores how certain key domains could develop. What would geopolitics, economic growth, demographics, resources and climate, agriculture, and technology and investment in food systems look like in each future? How each key driver would materialise in each future is also illustrated. For instance, the driver ‘Innovation and Science’, in the MOS scenario, imagines that various agricultural technologies such as robotics, blockchain and AI were developed and were expected to support data-driven transformation but failed in the face of too much focus on means and not enough institutional and social innovation. In the AFU scenario, some investments in novel technologies helped improve productivity and resource use efficiency.

However, more systemic approaches such as agroecology and multi-cropping were not followed through and unequal investment across countries took place, meaning that real transformation was incomplete. In the RAB scenario, science was further used to ensure control of corporate entities or geopolitical allegiance, reinforcing inequalities and further exclusion of small-scale actors and leading to faster exhaustion of natural resources. Finally, in the TOS scenario, science and innovation are fully geared toward sustainable food systems and involve strong contributions from educated and aware civil societies using innovative decision-making processes. Greater awareness of consumers facilitated the trade-off of outputs with sustainability and supported the creation of a diverse and resilient agri-food system across communities.

Various assumptions always play a role in developing scenarios and their policy triggers. Compared to previous scenario exercises, a key assumption, due to updated data models and prognoses, is that the collapse of substantial parts of agri-food, socioeconomic and environmental systems is almost certain(!). A second important assumption in the TOS and RAB scenarios is that ‘globally emerging well-educated, informed, critical, increasingly aware and non-manipulable civil societies’ are a crucial factor that either can enable or prevent those futures from being realised. Another assumption is that governance of markets is important to address inequalities. This is contrary to scenarios developed by the World Economic Forum, where the assumption was that if markets are connected and economic growth is fast, inequalities will also decrease.

So, what does it mean to work with these futures?

Concluding most directly: the picture is not reassuring, but something can be done if with urgency. SDG achievement is off track, finding ‘win-win’ solutions is difficult if not impossible, and MOS and RAB scenarios must be avoided with great urgency as they could very well become reality. However, the implications of the scenarios and the complexity of food systems also mean that other lessons require deeper reflection. Two elements are essential to underline: the interconnectedness of systems and our abilities to boost transformative change.

The interconnectedness of systems means that negative trajectories and global challenges can cascade into even bigger crises. Solutions cannot emerge easily due to entangled problems within agri-food, socioeconomic and environmental systems. Climate change, shock resilience, sustainable resource use, poverty and ending hunger are at the top of overarching challenges.

Agency grants us the means to set a new path, but it may be challenging to implement change under the influence of drivers and opposing power and interests. As such, being on the path toward MOS or RAB does not mean that we cannot set in a new direction. We must utilize ‘priority triggers of change’ or boosters of transformative processes to move away from business as usual. The report identifies four key policy triggers: institutions and governance; consumer awareness; income and wealth distribution; and innovative technologies and approaches.

Following a systemic logic, changes made through these triggers within the agri-food system should also impact socioeconomic and environmental systems. Activation or deactivation of these triggers (especially regarding which stakeholders gain the power to influence the manner of their activation) will highly influence the realisation of certain scenarios. For instance, better institution and governance mechanisms will influence on a range of key drivers and domains, such as better institution and governance mechanisms will influence on a range of key drivers and domains, such as governance of new technologies, migration, market power and intergenerational equity.

The report concludes with the words of Antonio Gramsci, Italian philosopher and radical journalist. “My mind is pessimistic, but my will is optimistic. Whatever the situation, I imagine the worst that could happen in order to summon up all my reserves and will power to overcome every obstacle”: words to be taken to heart. Acceptance of long-term perspectives by citizens and their governments is crucial for transformative action to start now. We must ‘outsmart’ political-economic constraints and enlarge agency space.

As Foresight4Food, we are committed to promoting and enhancing foresight approaches to strategically prepare for different food systems outlooks, by learning from the past but especially looking forward to explore.