By Bart de Steenhuijsen Piters

Foresight4Food is organizing its 5th Global Workshop in June titled “Foresight for Transformative Action in Food System”. To raise the tip of the curtain on this exciting event, we have asked Bart de Steenhuijsen Piters, Senior Scientist Food System at the Wageningen University and Research and Foresight4Food FoSTr programme facilitator, to share some of his thoughts and expectations. Here is what he has to say:

The myth of the “Global” food system

As we approach the 5th Global Foresight4Food Workshop in Jordan, I find myself reflecting on what it truly means to transform our food systems—and what role foresight can play in helping us get there.

Let me begin with a provocation: I believe the idea of a global food system is, in many ways, an illusion.

When we speak about the global food system, we often forget that it’s simply the aggregation of countless national and subnational systems. No one actor is responsible or able to govern it. The UN may think so, but that is an illusion. Instead, we have trillions of individuals, institutions, and businesses shaping the system every day. This diffused responsibility makes governance incredibly complex and leads to a kind of mystification, where the real (geo)political and economic dynamics at lower levels are ignored or misunderstood. Yet, all these food systems are connected for sure. Just look at the effect of the Trump administration and its tariff policies on food markets worldwide.

This is precisely where foresight can help—not by giving us a top-down blueprint but by helping us navigate complexity, anticipate challenges, and co-create transformative pathways.

What success looks like for the 5th Global Foresight4Food Workshop

For me, success for the 5th Foresight4Food Workshop doesn’t lie in just producing new scenarios. It lies in helping us figure out how to act in those scenarios.

I want us to co-develop a joint narrative around food system transformation. I want us to compare how different countries are exploring their options. Most importantly, I want us to dive into the real-world, practical question: how do we move from insight to impact? How do we build pathways for change that involve multiple actors, each taking responsibility? And how do we lead, especially when the pathway forward is contested and uncertain?

These are the questions I hope we will tackle together in Jordan.

Regional collaboration is crucial

One of the most powerful levers for transformation is regional cooperation. Not only does it allow us to share experiences and foresight approaches among practitioners, but it also aligns with the need for more localized, resilient food systems. This is especially critical in times when global markets are being challenged, multinational food companies continue to concentrate their power and food is more and more used for geopolitical purposes.

We need shorter, regional supply chains and production systems that are better tailored to local contexts. Regional platforms are essential for this. They help us valorise knowledge and foster innovation where it matters most—on the ground.

The leadership we need

Food system transformation demands leadership on many fronts.

We need business leaders who are willing to shift course—who can rethink business models that currently drive unsustainable outcomes and align their strategies with public goals like healthy diets and environmental sustainability.

But we also need leadership that can manage conflict and mediate between diverse interests. Sometimes, this means making bold policy decisions, even when powerful actors resist change. That kind of leadership isn’t easy—but it’s necessary.

A call for courage and collaboration

My hope for this workshop is that it becomes a space of real collaboration. A space where participants listen to each other, share not only their successes but also their failures, and resist the urge to simply push their own agendas.

We need the courage to explore the unknown together. To ask hard questions. To face the uncomfortable truths. Because only then can we unlock the systemic changes our societies so urgently need—and that, too often, are still moving too slowly or stalling altogether.

I look forward to learning with and from all of you in Jordan.

By Jim Woodhill, Lead Foresight4Food Initiative

How can we understand the multiple dimensions of transforming food systems? On top of the disruptions to peoples’ incomes and food supply chains caused by COVID, the Russia war in Ukraine has pushed fertilizer, energy and food prices to all-time highs. Millions are falling back into hunger and poverty. Even in the affluent world, many poorer people in society are being forced to use food banks, eat lower nutritional value food, and make tough decisions between using their dwindling financial resources to pay for food or keep their houses warm in winter.

This situation underscores the conclusions of the UN Secretary General’s 2021 Food Systems Summit that highlighted the need for a far more resilient, equitable and sustainable food system. Heads of state universally declared that a transformation of food systems is needed to cope with climate change, tackle hunger and poor nutrition, reduce poverty, and protect the environment.

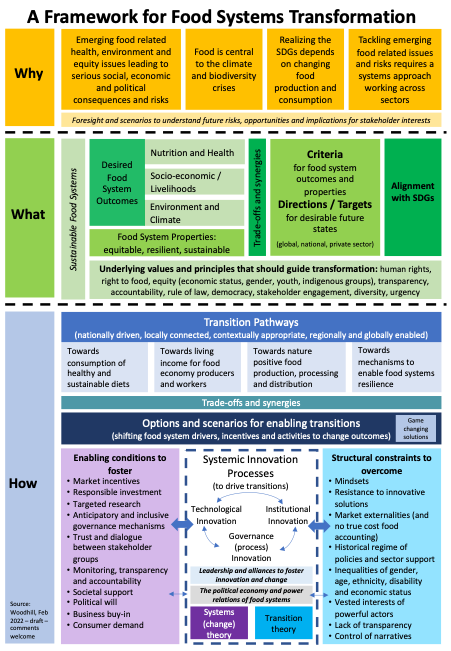

But what does food system transformation actually mean? In this blog, I outline a framework (Figure 1 below) for thinking about food systems transformation. It is based on WHY change is needed, WHAT needs to change, and HOW change can be brought about.

Introducing food systems transformation

“Food systems” has provided a new framing for a more integrated approach to the issues of food security and nutrition, agriculture, climate change, environment and rural poverty. This systems view makes a lot of sense as, one way or another, how we consume and produce food is central to all the Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs). Billions of people work in the agri-food sectors, everyone needs a healthy diet, food is central to culture, food trading and retailing are huge markets and agriculture is the biggest user of land and water resources.

This systems perspective is bringing together a plethora of associated ideas, language and concepts. Terms such as food system outcomes, transformation, transition pathways, resilience, equity, trade-offs and synergies, living income, nature positive approaches, agroecology and the true-cost of food are just a few of these. The emerging food systems discourse is also giving more attention to power structures, the political economy, stakeholder engagement and dialogue, empowering excluded voices, market externalities, coalitions, economic incentives, and data needs.

Before explaining the framework, let’s ask what is meant by a transformation of food systems. Transformation means a complete or radical change of something in form, function or appearance. So, transforming food systems means fundamentally changing how they operate to dramatically improve environmental, health and livelihood outcomes for society at large. This requires fundamental changes in the behaviour of consumers, investors, agri-food sector firms, farmers, researchers and political leaders. In turn, a dramatic shift in economic and social incentive structures is needed, with the true cost of food embedded into how markets function. To avoid future risks these fundamental changes are needed with urgency.

To-date, and perhaps not surprisingly, much of the debate and political narrative has focused on what needs to change and why. The more difficult question of how change can actually be brought about has so far received less attention. Perhaps this is because such discussion cannot avoid difficult political-economic issues of long-term collective interests versus short-term vested interests. We are still a long way from having sufficiently detailed strategies, plans of action, policy commitments and investments to bring about the transformation. How to get from WHY to HOW?

WHY transform food systems?

Why food systems need to change has been well analysed, is clear to most stakeholder groups, and is increasingly articulated by political leaders. The problems and longer-term impacts and risks of the way food is currently consumed and produced is well-evidenced in terms of the negative consequences for health, the environment, and equitable economic development. If this interconnected set of issues is not tackled effectively and promptly the risks of dire longer-term social, economic and political consequences are high.

Food value chains contribute about a third of total greenhouse gas emissions. Agriculture and fishing are by far the largest causes of biodiversity loss and ecosystem degradation. These impacts on the environment cycle back to undermine the Earth’s very capacity to produce food for the long run.

Further, it is increasingly clear that the SDGs and in particular SDG1 – no poverty – and SDG2 – zero hunger – will not be achieved without a fundamental change in how food systems function.

The work of the Food Systems Summit brought a much wider understanding and acceptance that the numerous development issues linked to food can only be effectively dealt with through a cross-sectoral and systems-oriented approach. An additional critical aspect of the food systems framing is an acceptance that these issues are of equal importance for countries in the Global North and the Global South.

Foresight and scenario analysis can make a vital contribution in helping to explore the ways food systems might change and with what risks and opportunities for different stakeholder interests.

WHAT needs to be transformed?

The desired outcomes from food systems have become well-articulated in terms of three main areas:

- ensuring food security and optimal nutrition for all.

- meeting socio-economic goals, in particular reducing poverty and inequalities.

- enabling humanity’s food needs to be met within planetary environmental and climate boundaries.

Overall, food systems are recognized as needing to function with the properties of being resilient to shocks, sustainable over the long-term and equitable in terms of the costs and benefits to different groups in society.

Across these food system outcomes and properties, there are inevitable trade-offs and synergies, which bring with them the potential for both conflict and collaboration between different interest groups. While the broad directions for desired food system outcomes and properties are relatively well established, the nature and extent of these synergies and trade-offs is much less well understood. More work is also needed to establish specific criteria, directions for change and targets for food system outcomes, which will be necessary to guide transformation at national or local levels, within sectors or across business operations. More attention needs to be given to how the criteria and targets for food systems transformation align with those of the SDGs.

The Food Systems Summit and the work of the Committee on World Food Security (CFS), in particular its recently adopted Voluntary Guidelines of Food Systems and Nutrition (VGFSyN), have identified underlying values and principles that should guide the processes and outcomes of food systems transformation. These include human rights (incl. the right to adequate food), sustainability, resilience, transparency, accountability, adherence to the rule of law, stakeholder engagement, gender equality, and inclusivity (particularly for women, youth, indigenous groups and small-scale producers).

Food systems that deliver on the desired outcomes and properties, and function in adherence with the underlying values and principles articulated above, can be considered as sustainable food systems.

HOW can food systems be transformed?

The transformation of food systems will require a focus on transition pathways, largely driven at the national level but connected with local processes and enabled by larger-scale system shifts at regional and global scales. Four main transitions can be identified from the Food Systems Summit deliberations:

- a consumption shift to sustainable and healthy diets.

- an equitable economic shift to ensure food economy producers and workers, have a fair living income including being able to afford healthy diets.

- a shift toward nature positive approaches for food production, processing and distribution which have a net-zero climate impact and operate within a sustainable and safe zone of utilizing natural resources.

- a shift towards mechanisms of resilience for food systems which can ensure societies a large to not risk food insecurity and that groups who are poor or vulnerable are protected.

Desired food system outcomes can potentially be achieved through multiple different pathways and scenarios with numerous different trade-offs and synergies. For example, consumption shifts could be influenced by food prices and taxes, public education, product labelling or shifts in food marketing practices. Resource efficiency and circularity could be achieved by a number of measures, including consuming (at a global level) less animal protein, adopting agroecological approaches, energy efficiency, water management, reducing waste, or new technologies which reduce methane emissions from cattle farming. Equity for those working in the sector could be improved through various combinations of increasing food prices, implementation of labour and land tenure rights, improved social protection, improving overall rural economic development or creating greater economic opportunity outside the food sector.

Developing and assessing the options and scenarios to enable transitions is where a vast amount of investment and work is needed if food systems are to be sustainably transformed. The Food Systems Summit process identified a significant number of “game changing solutions”, ideas that could contribute to developing viable transition pathways. Further assessment and work will be needed to refine, prioritize and build on this contribution from the Summit.

Scenarios can help identify potential trade-offs and co-benefits of those solutions across intended food system outcomes. The principles of equity and inclusion are especially important to consider when analysing options and trade-offs. For example, gender equality is not guaranteed to improve with increased income from food systems activities, so attention must be paid to gender-transformative and inclusive value chain development.

Generating viable options for transforming food systems will require systemic innovation that connects processes of innovation across the domains of technology, institutions and social norms, and politics and governance. Food systems transformation will be impeded or enhanced depending on the constellation of power relations across societies and the agri-food sector. This is particularly salient where influential actors are prepared to defend vested interests at the cost of changes for the wider collective good. Such systemic innovation will require profound paradigm shifts and completely new approaches to policy coherence.

Insights from systems theory and transition theory have much to offer in terms of how to guide and broker change in complex (food) systems. For example, encouraging, supporting, linking and scaling up “niche” innovations that can respond to new needs, challenges and opportunities. This requires adaptation to local contexts that can be supported by territorial approaches to development. Over time, such innovations can help to disrupt existing and unsustainable food systems “regimes” (attitudes, policies, power relations, market relations) and enable more sustainable alternatives to become embedded.

The Food System Summit has helped to identify numerous factors that can be considered as enabling conditions or structural constraints for food systems transformation. Systems change involves “nudging” systems in desirable directions by working to amplify enabling conditions and dampening structural constraints. This requires attention to the underlying political economy. Strategic alliances and political leadership are needed to help shift understanding, narratives and power dynamics.

In October 2022, Foresight4food hosted a CFS side event on “Foresight and Future Scenarios for Food Systems Transformation – Building Resilience and Fostering Adaptation to Protect Against Future Crises”. The event was held jointly with the International Fund for Agricultural Development (IFAD), the Forum for Agricultural Research in Africa (FARA) and the CFS High Level Panel of Experts on Food Security and Nutrition (HLPE – FSN).

The event highlighted the importance of taking longer-term perspectives on food systems transformation through the use foresight and scenario analysis. The work of the Foresight4Food Initiative was outlined and a new programme “Foresight for Food System Transformation – (FoSTr)” was launched.

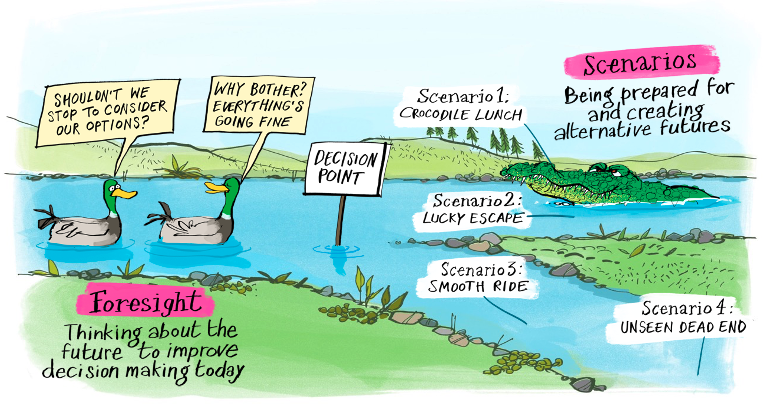

Patrick Caron, International Director at Montpellier University of Excellence / CIRAD opened the event and highlighted the potential of foresight for supporting food systems transformation. He emphasised that foresight is not about trying to predict the future but rather to prepare for a range of different future scenarios and to understand the implications of these for different stakeholder interests. Patrick introduced the work of Foresight4Food, which is promoting and supporting the use of foresight and scenario approaches for food systems analysis and transformation.

The event was moderated by Jim Woodhill, Lead of the Foresight4Food Initiative. He introduced the building blocks of an approach to foresight for food system transformation which has been developed by Foresight4Food. Central to this approach is identifying key trends and critical uncertainties which may influence the future of the entire food system. He indicated how Foresight4Food has been developing and how its overall approach is being tested through work in Africa and Asia. This contributes to the Foresight4Food objectives of supporting a community of practice, a brokering foresight work and developing a deeper understanding of foresight methodology and tools.

Abdurazak Ibrahim, Cluster Lead, Institutional Capacity and Future Scenarios, Forum for Agricultural Research in Africa (FARA) introduced the work of the African Foresight Academy in institutional capacity building for foresight and scenarios. He outlined the objectives of Academy and introduced current initiatives. This includes running an AgMOOC on foresight for which 300 people have enrolled and which has been produced in partnership with Foresight4Food.

Akiko Suwa-Eisenmann, a member of the HLPE-FSN, discussed the most recently presented HLPE-FSN report no. 17 on “Data collection and analysis tools for food security and nutrition” which focuses on enhancing data for effective, inclusive and evidence-informed decision making. Akiko emphasised that the current food crisis further illustrates that it is critical to have reliable and up-to-date data on food and nutrition security. Challenges to be faced include enhancing data literacy, dealing with the complexity of food systems across scales, filling critical data gaps, and synthesising and presenting data so it is useful for decision making. Akiko noted that “foresight needs to be data informed and that means not only data collection and analysis but also translating data into insights, and dissemination for making decisions, and that foresight is key in these processes of bringing data to the public debate”. She also highlighted the value of linking the work of the HLPE and that of Foresight4Food.

John Ingram, Lead of the Food Group at the Environmental Change Institute, and Associate Professor and Senior Research Fellow at Somerville College, University of Oxford, introduced and launched the new Foresight for Food System Transformation (FoSTr) Programme. This will be a three-year initiative helping to take forward the work of Foresight4Food with engagement in five focus countries across Africa, Asia and the Middle East. FoSTr is funded by the Government of the Netherlands, as a grant through the International Fund for Agricultural Development (IFAD). He talked about the collaborative nature of this work at both national and global levels and its intention to support a growing community of practice across foresight providers and users.

Read Also: Successful launch of the FoSTr Programme in Jordan during fruitful roundtable on future food systems

Sara Savastano, the Director of IFAD’s Research and Impact Assessment Division, discussed the need to understand how food systems work in the selected countries where FoSTr will operate. She noted the importance of foresight as a key contributor for designing effective investment projects which tackle the longer-term challenges of building resilience into food systems.

Ravi Khetarpal, Executive Secretary of Asia Pacific Association of Agricultural Research Institutions (APAARI), and Chair of the Global Forum for Agricultural Research (GFAR) underlined the continued importance of the agri-food sector for security and development across the Asia Pacific. He emphasised the critical need for multi-stakeholder platforms at national and local levels to help drive the needed innovation for transforming food systems. He saw foresight and the Foresight4Food initiative as a valuable contribution to such processes and welcomed its work in the region. To achieve sustainable and resilience food systems he called for more evidence-based policy making, which relies on good data and the type of integrated qualitative and quantitative analysis which can be offered by foresight.

Sara Mbago-Bhunu, the Director of IFAD’s East and Southern Africa Division, highlighted the current crises across the region being driven by increasing energy and food prices, along with climate impacts. She welcomed the FoSTr initiative and noted the critical need to transform food systems for long-term resilience while also tackling the humanitarian relief demands in the short-term. She emphasised the historical link between high food prices and social unrest and reminded the audience of the huge shortfall in investment funds for the agri-food sector. She hoped that “the FoSTr program as you have described here can do the modelling and forecasting to build up capacities in this space for informed policy making to invest in sustainable and circular management [of food systems]”.

Winnie Yegon, a Horticulture Fellow with the African Food Fellowship, and food systems expert with the Food and Agriculture Organisation (FAO) explained how training in food system foresight provided by the Followship Programme, has enabled new perspectives on how to bring about change in food systems. In particular, she noted the value of an integrating perspectives that brings stakeholders together to make sense of available data.

Herman Brouwer, Senior Advisor for Multi-Stakeholder Collaboration at the Centre for Development Innovation (CDI), Wageningen University and Research, highlighted two key implications from the discussion, on one hand the need for reliable data and on the other the need for processes which enable collective sense making. He noted that helping to bring enhanced literacy on data and foresight processes is a valuable contribution which can be made by Foresight4Food and the FoSTr Programme. In particular, he emphasised the need for collaboration between different stakeholder across the food system to enable change, and that foresight can make a valuable contribution to such collaborative processes by creating shared understanding of future risks and opportunities.

Key Messages

- The current crisis in energy and food prices underscores the need for food systems transformation with a central focus on resilience.

- Transforming food systems requires long-term perspectives and futures thinking which can be supported through foresight and scenario analysis.

- Foresight is most valuable when it can integrate qualitative and quantitative methods and engage stakeholders from across the food system.

- Foresight4Food offers a network and platform for sharing experience and methodology on foresight for food systems change, and for supporting capacity development.

- Foresight needs good data on food security and nutrition, however, there remain large gaps in data availability and limited literacy on how to collect and analyse data.

- The Foresight for Food System Transformation (FoSTr) Programme will provide three years of support for the work of Foresight4Food and enable in-depth work in five focus countries.

- Enhancing food systems and foresight literacy across key players in food systems is increasingly recognised as an important element in being able to transform food systems and take forward national food systems transformation pathways.

By Jim Woodhill, Lead Foresight4Food Initiative

A dramatic and rapid transformation of food systems is necessary to end poverty and hunger, protect the environment, improve rural livelihoods, and ensure resilience to future shocks. This transformation must include structural changes in how our political, economic, social and technological systems function. Such transformative change requires a long-term perspective and understanding of the risks and opportunities in different possible food system futures – the purpose of foresight.

Foresight and Food Systems

Foresight offers one approach to support transformational change for a more equitable and sustainable global food system. It uses futures thinking and scenario analysis to help diverse food system actors (e.g., rural farmers, food manufacturers, small agri-food businesses, governments) imagine, together, how the future might unfold. Considering future scenarios enables possible risks and vulnerabilities to be understood and mitigated. It also enables opportunities for positive food systems transformation to be identified and explored.

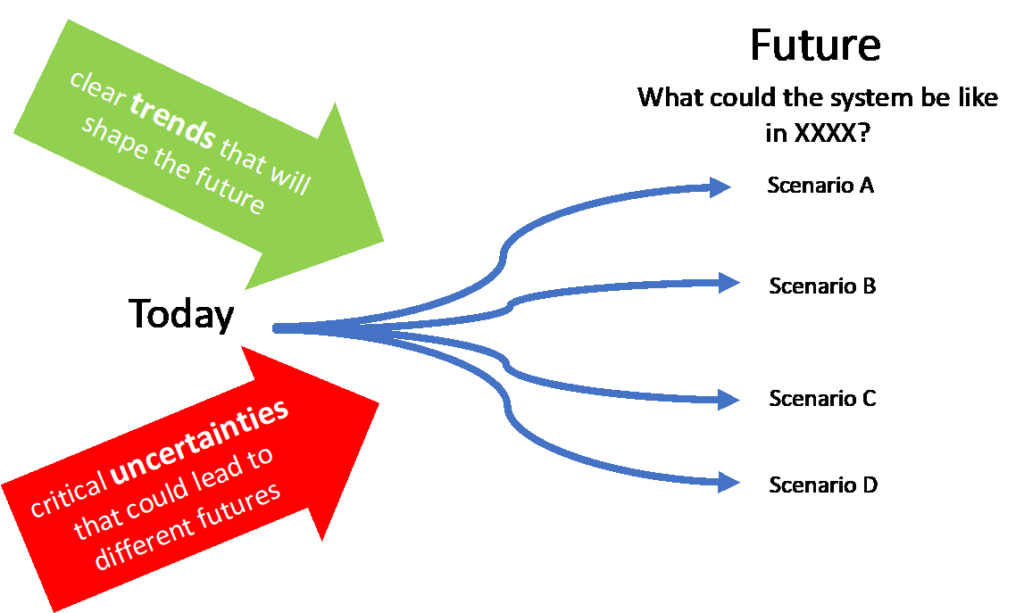

Foresight analysis helps to create understanding about how key trends and critical uncertainties (e.g., changing diets, climate impacts, demand for certain foods) could impact food systems. It supports preparedness for different possible futures.

Food systems are extremely complex, with all of the activities of food systems from production to consumption affecting global health and nutrition, environmental sustainability, and livelihoods and employment. Globally, agri-food work is the largest economic sector, employing over a quarter of the world’s workers. The scale alone of global food systems makes achieving change complicated and slow. Fear of the unknown, combined with vested interests of powerful food systems players, can bring resistance to innovation and change. This results in a lack of effective responses to already pressing issues. The challenge Is compounded by the difficulties of creating sufficient collective understanding and commitment among the highly diverse groups involved in food systems.

However, while change often seems slow and difficult, stuck or even regressing, there are endless positive examples of individuals, communities, groups and organisations working for more sustainable and equitable food systems. Especially when the life force of food is involved, people are deeply capable of innovation, creativity, social organisation and activism.

However, while change often seems slow and difficult, stuck or even regressing, there are endless positive examples of individuals, communities, groups and organisations working for more sustainable and equitable food systems. Especially when the life force of food is involved, people are deeply capable of innovation, creativity, social organisation and activism.

While foresight and scenario analysis is no panacea to the complex and overlapping issues within our food systems, it offers two critical contributions:

- Motivation and clarity for change by offering stakeholders a window into the future, through which they can see how their longer-term interests and aspirations would be affected by different future scenarios.

- Helping break down the barriers of vested interests by facilitating stakeholders to collectively explore options and pathways for change that can balance individual and common interests.

The Foresight4Food Approach

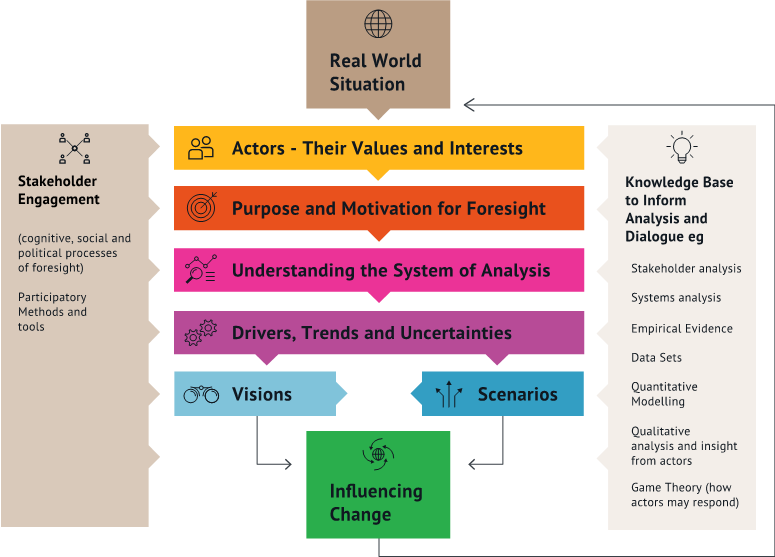

The Foresight4Food Initiative has developed a framework and process to guide foresight and scenario analysis for food systems change. The framework (Figure 1) links a participatory process of stakeholder engagement with a strong scientific evidence base and the use of computer-based modelling and visualisation. The approach starts by understanding how food system actors “see” the food system – their actions, values and interests – and their motivation for engaging in foresight. It maps out and examines how social, technical, economic, environmental and political (STEEP) factors interact within food systems, and how food systems are influenced by the power dynamics between actors.

A food systems framing is critical to identify and assess key drivers, trends and uncertainties, to develop alternative future scenarios (Figure 2). The approach creates dialogue between stakeholders about their assumptions on how the future food system may unfold and what this implies for their visions and aspirations. The discussions that ensue provide a foundation for exploring what directions for food systems change would be in the collective interest and how trade-offs or synergies between the specific interests of different groups can be best managed.

Central to this approach is the development and analysis of future food system scenarios, based on data about key trends and critical uncertainties. This is often the most challenging yet insightful part of the process. It takes various actors ‘outside the box’ to imagine how the future of food systems could be fundamentally different, with what implications.

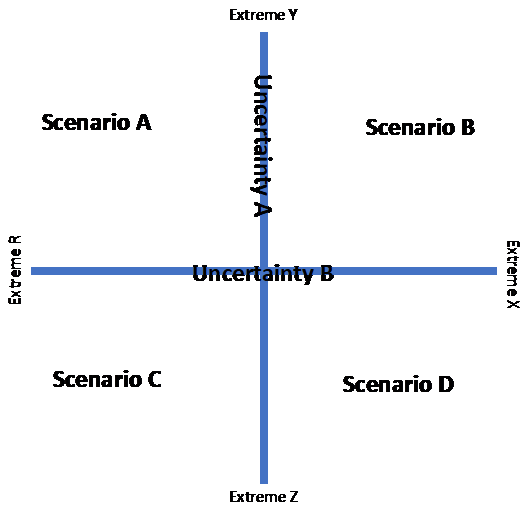

A simple way to develop scenarios is to identify two independent critical uncertainties that then create a matrix of four different scenarios (Figure 3). For example, critical uncertainties in food systems could be dietary changes, climate impacts on agricultural production, malnutrition levels, market and trade functioning, and many others. Scenario story lines are then developed that outline what each of these four futures would be like, based on the two chosen uncertainties. ‘Back casting’ is used to look backwards from an imagined future scenario to construct the possible events and decisions that could have led to such a future.

The framework integrates four elements:

- A futures orientation that invites stakeholders to develop a longer-term perspective on how food systems may unfold in the future, and what decisions are needed today to avoid future risks and build resilience into our food systems.

- Ways of thinking about how change happens in food systems – by linking theories and schools of thought on complex systems, socio-technical transitions, wicked problems, anticipatory governance, cognition, and human bias.

- Practical methods from strategic foresight, scenario planning, multi-stakeholder processes, soft systems analysis, and theory of change.

- Participatory tools for analysis and group facilitation, which enable food system actors to collectively analyse situations and data, create scenarios, engage in dialogue and critical conversations, build trust, and generate pathways of action.

Rethinking Food System Change

Foresight4Food’s approach recognises that elements in the system (i.e., people and nature) interact in complex and adaptive ways; therefore, change in food systems does not occur in easily predicable or linear and hierarchically controlled ways. The complex nature of food systems deeply challenges reductionist mindsets that continue to dominate in public policy making and organisational management. Food systems thinking recognises that change happens through nudging systems, rapid experimentation and learning, and scaling niche innovations. It explores how locked in structures and power relations can be disrupted, yet recognises that building the foundations for desired change takes time, with the eventual outcomes and moments of change being uncertain.

Food systems transformation will require ongoing innovation and learning, with strong networks to obtain feedback and decentralised responsibilities for decision-making and action. Real changes in food systems will depend on shifting underlying structures related to power dynamics, relations between different actors, and the mental models of society, leaders and politicians. Foresight and scenario analysis can help to surface and examine these dimensions of change in a complex and adaptive food system. It is an approach to help generate the critical thinking, leadership and stakeholder engagement needed for food systems transformation.

COVID-19 is a deep disruption to human systems. The world is having to muddle through huge uncertainties about the consequences and longer-term impacts. This requires ‘thinking the unthinkable’ and exploring ‘neglected nexuses’. A key issue is how food system recovery pathways might unfold, especially given the “Build Back Better” mantra now being voiced by many leading decision makers.

Even before the outbreak it was clear that a profound a transform of food systems is needed for good nutrition, inclusive development and environmental sustainability. This combined with major concerns about the resilience of food systems, particularly in the face of climate change, led the UN Secretary General to call for a Food Systems Summit in 2021.

The current economic and social crisis induced by COVID-19 underscores the critical need for food systems that are resilient to shocks (particularly given underlying stresses), and which in times of crisis can protect the welfare of all, especially poor and vulnerable food producers and consumers.

Over the last months many assumptions and projections about poverty levels, nutrition, food trade, vulnerability of different groups and achievement of the SDGs have gone out the window. Scenarios of increased poverty and inequality are seeming far more likely. Updated perspectives, framing and insight are urgently needed. Leadership, decision making, and advocacy have a critical need for rapid “collective intelligence” gathering and synthesis about what is happening to food systems, emerging risks, opportunities, and the options for responding.

However, in these times of turbulence, uncertainty, novelty and ambiguity (TUNA), conventional data collection, modelling and analytical mechanisms are not enough. They need to be be complemented by greater attention for existing scenarios and analysis that highlight the risks of global disruptions, and by additional intelligence gathering to provide rapid and meaningful insights into what post COVID-19 futures might look like.

This calls for sense making and decision processes appropriate to high levels of complexity and uncertainty. Such processes need to draw on human capabilities for perceiving, communicating and recognising complex patterns, which can be connected into networks for collective intelligence and adaptive responses. There is well developed theory and methodology to support such an approach. In essence it involves:

- Creating heightened and rapid ‘situational awareness’ through sensing methods that ‘probe’ for critical changes in systems using peoples experience to judge what is important and significant, while using diverse perspectives and dissent to also detect ‘weak signals’.

- Sense making through opening up spaces for structured collective deliberation by actors with diverse backgrounds, experience, perspectives and interests, and making use of rapidly sourced coherently structured ‘narrative information’.

- Engaging stakeholders and decision makers in well informed scenario thinking about risks, opportunities and transformative pathways.

- Reconfiguring decision making and innovation through more inclusive and diverse forums that engage decision makers in processes built around principles of complexity analysis and scenario thinking.

Over the coming weeks Foresight4Food will be working with the Forum for Agricultural Research in Africa (FARA) to provide an online webinar series to help practitioners use foresight and scenario approaches to assess the potential impacts of COVID-19 on food and agriculture.

Blog by Jim Woodhill – Foresight4Food Initiative Lead