By Jim Woodhill, Foresight4Food Initiative Lead

Last month (November 2023) I had the wonderful experience of engaging with over fifty young leaders from across Africa, joined by colleagues from Bangladesh, Nepal, and Jordan. We had all gathered in Naivasha, Kenya, to explore how skills in facilitating foresight can be used to help bring about food systems transformation.

The fascinating work these young leaders are involved in and their deep interest in understanding how to be more effective change-makers was truly inspiring. It was encouraging to see how valuable they found the foresight for the food systems change framework and the associated set of participatory tools for engaging stakeholders.

Participants all came with projects from their own countries where they are keen to use foresight and systems thinking to help facilitate change in food systems by bringing together different stakeholders. The participants were from diverse backgrounds representing policy, the private sector, NGOs, and academia.

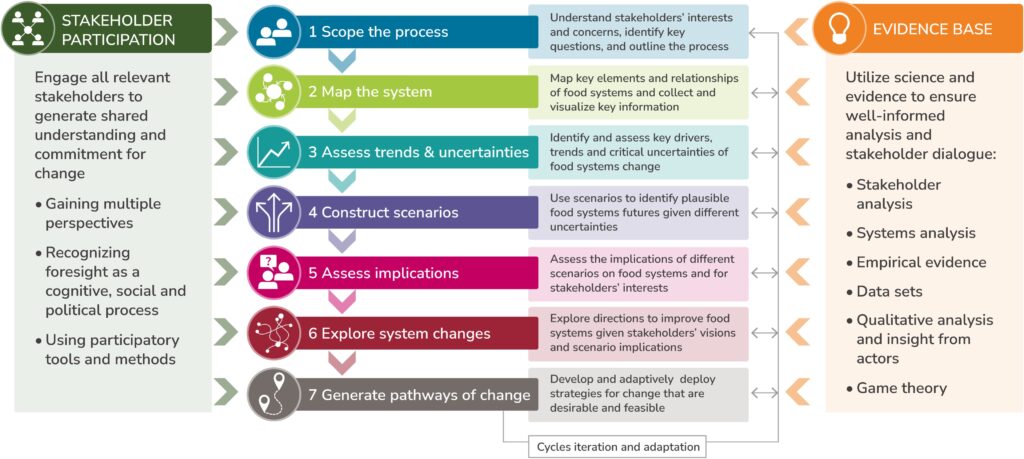

A Guiding Framework: During the workshop we introduced participants to an overall guiding framework for facilitating foresight for food systems change. A range of participatory tools were used for systems analysis, development of future scenarios and exploring systemic interventions. To bring reality into the workshop, the Kenya horticulture sector was used as a case study for the foresight analysis. Participants spent a day visiting horticulture farms, packing and processing facilities and the local market. They explored with local stakeholders how they saw the future for the horticulture sector and the issues that “keep them awake at night”.

Visualising the system: The workshop was highly interactive with participants practicing in the facilitation of a range of participatory tools which can be used to bring stakeholders into dialogue around systems change. One of my favourite participatory tools “rich picturing”, which enables a diverse group of stakeholders to develop a shared understanding of a system by drawing it, was found by participants to be especially powerful.

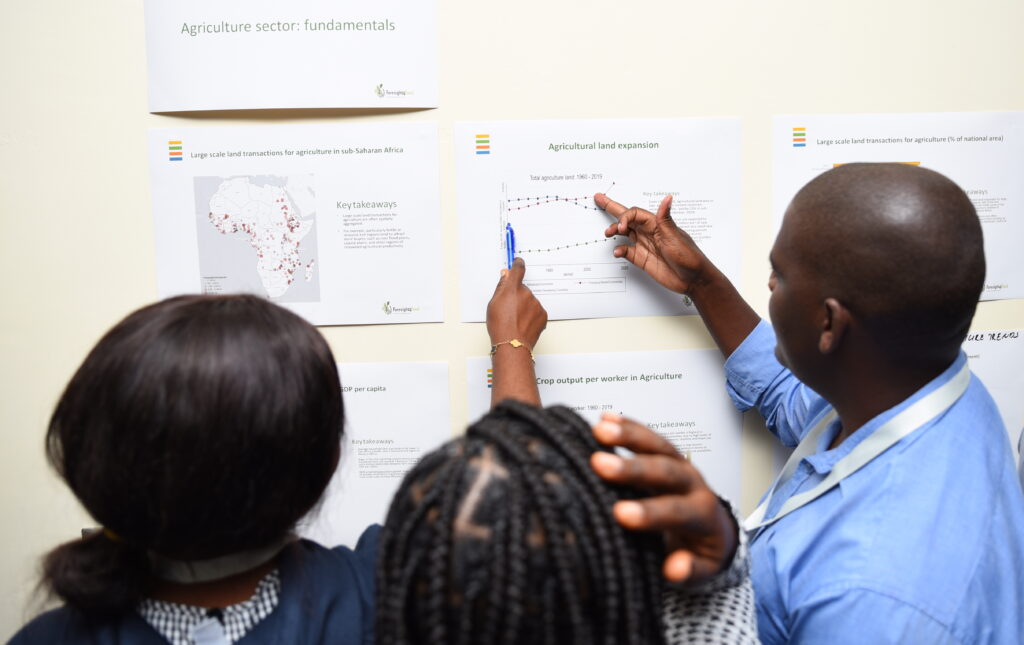

Data-driven dialogue: To go deeper into the systems analysis it is valuable for stakeholders to explore the available data on key drivers and trends. Over 100 graphs visualizing key data points related to the Kenya horticulture sector and food systems at national, continental, and global scales were collated and posted around the walls. The participants then explored this data in groups of three and discussed its implications and how it perhaps challenged their existing assumptions.

Exploring the future using scenarios: Central to the foresight approach is developing a range of different plausible future scenarios (generally with a 10 to 30-year horizon) for how the system might evolve given critical uncertainties. Workshop participants did this for the horticulture sector, looking at factors such as how diets might change in the future, regional and global trading relations, severity of climate change, and the enabling policy environment for small-scale producers and the small- and medium-scale enterprises (SME) sector. The scenarios help to identify future risks and opportunities for different stakeholder groups and society at large. They also help to unlock creative thinking about how to “nudge” systems towards more desirable futures and away from less desirable ones.

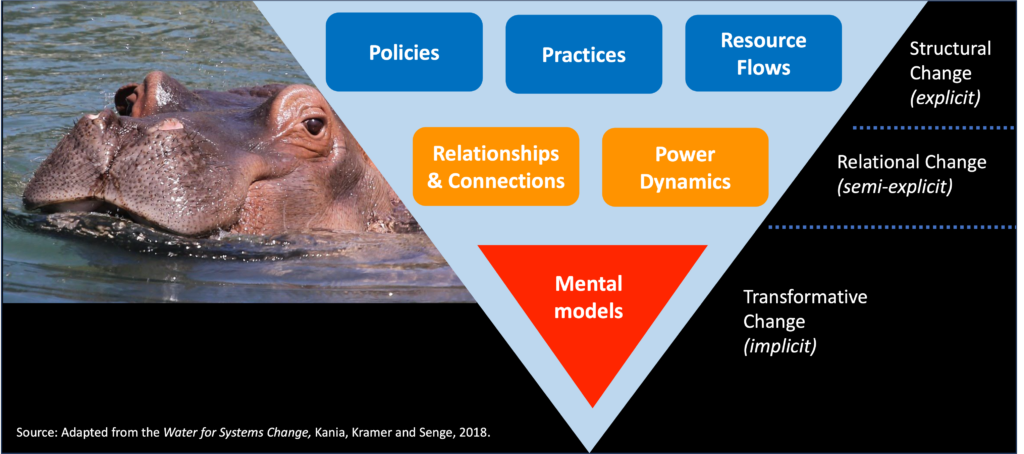

The deeper issues of systems change: It is easy to talk about systems change. In reality trying to change systems bumps into all the difficult issues of vested interests, power relations, ideologies, and deeply held cultural beliefs. On top of this human and natural systems are complex and adaptive and behave in self-organising, dynamic, and often unpredictable ways. It doesn’t mean you can’t intervene to try and bring positive change. But it does mean that top-down, linear, and mechanistic models of change generally don’t work. The workshop engaged participants in deep and challenging discussions about what it means to be a leader of systems change. This included the need to be adaptive, how to create alliances for disrupting existing power relations, the importance of building relations between diverse stakeholders, and the importance of patience. Systems change often requires taking time to build the foundations for change without being able to know when circumstances might suddenly unlock opportunities for big steps forward.

Identifying directions for change and intervention options: Developing directions and pathways for systems change is the most difficult and challenging part of the foresight for systems change process. It is highly context-specific and requires a deep insight into the political economy of the situation. Cause and effect mapping, theory of change thinking, and causal loop analysis can all help in identifying opportunities for intervening which could help to drive systems change in desired directions. Bringing change will often require an integrated approach to technological, institutional and political innovation. During the workshop causal loop diagrams were used to explore possible entry points for shifting horticulture systems in ways that could improve health, livelihoods and the environment.

New friends, new networks and big ambitions: After an intense week of learning and sharing participants left inspired to apply the foresight approach back in their own work environment. New friends were made and there were clear calls to find mechanisms to support ongoing networking and peer support.

Many thanks to the facilitation and support team who made a fantastic week possible, Gosia McFarlane, Marie Parramon-Gurney, Kristin Muthui, Bram Peters, Joost Guijt, Riti Herman Mostert, and Abdulrazak Ibrahim. The event was made possible by support from the Mastercard Foundation.

More information about the Foresight4Food Framework of Foresight for Food Systems Change can be found on our website, and an updated approach paper will be published in January 2024.

By Just Dengerink

Foresight training for Africa Foresight Academy by Foresight4Food researchers and Wageningen University & Research (WUR)

The Foresight4Food initiative aims to connect and inspire networks of foresight professionals around the world. In early July 2022, members of the Africa Foresight Academy participated in a foresight training at Oxford, provided by Foresight4Food researchers from the University of Oxford’s Environmental Change Institute (ECI) in collaboration with Wageningen University & Research (WUR). The training was attended by five African researchers in person, while five others joined in online.

The Foresight4Food ‘seven steps’ approach to scenario and foresight analysis (see illustration below) was used to develop four scenarios for a more climate-resilient Ghana in 2040. Here’s a look at how these scenarios were developed using the Foresight4Food approach in the training session.

Scoping the process and mapping the food system

The scenario exercise started with scoping and delineating the focus of the scenario process Collectively, it was decided to focus the scenarios on the future of the Ghana food system in 2040, and the resilience of this system to external shocks related to climate change.

Participants were invited to draw a ‘rich picture’ of the Ghana food system to map out its most important features. These included small-scale yam and cocoa production in the south, maize and sorghum production in the north, fisheries along the coast and around Lake Volta along with the role of urban informal food markets, the lack of a large food processing sector, Covid-19’s impact on supply chains, growing security threats in the region, and the effect of the war in Ukraine on fuel prices and availability of fertilizers.

From assessing trends and uncertainties to constructing scenarios

Building upon the key features of the Ghana food system from the ‘rich picture’ exercise, participants were then invited to identify the most important trends and uncertainties affecting the Ghana food system.

Highlighted key trends included fast population growth and urbanization, increasing use of technology, growing dependence on food imports and remittances, decreasing occurrence of crop diseases, growing youth unemployment, and the increase in fast food consumption.

Together, the participants also identified some important uncertainties regarding the future of the Ghana food system: the degree of extreme weather events, the implementation efficiency of climate resilience policies, and the vulnerability of households to climate change. Other uncertainties identified included future access to fertilizers, fluctuations in fuel prices, changes in trade regimes, levels of agricultural productivity, the expected value of the Ghanaian currency, the potential influence of future Covid outbreaks and the impact of developments in the general security of the region.

The participants then decided on two key uncertainties that would be critical in determining the future climate resilience of the Ghanaian food system. Based on these two key uncertainties, a matrix was created with each of the axes representing one uncertainty. Within this matrix, four scenarios were constructed, based on their position on both axes and with input from the other uncertainties that were identified.

Assessing implications, exploring system changes and designing pathways

With the four scenarios in place, participants were invited to give more colour to these four plausible futures by exploring the implications of each scenario for different stakeholder groups. One group explored the implications for rural farmers, while the other focused on urban consumers.

With the implications of each scenario explored in more detail, participants were asked to zoom out and think about the possible system changes that – in each scenario – could contribute to a more climate-resilient future of the Ghanaian food system. Suggestions included the stimulation of climate-smart agriculture practices, diversification of production and dietary patterns, strengthening regional trade, supporting home gardens and peri-urban agriculture and digitalization of supply chain management.

This three-day exercise with African foresight experts showed how the Foresight4Food approach can help structure a participatory foresight process that leads to engaging scenarios and actionable policy recommendations to shape the future of our food systems.