By Zoe Barois

Like many other countries, Bangladesh is working to develop it’s Food Systems Transformation Action Plan. This will be presented during the United Nations Food Systems Summit Plus 4 Stocktaking event. On November 6 and 7, Foresight4Food collaborated with GAIN Bangladesh to host a workshop on how foresight could contribute to the development of the Action Plan.

If transforming food systems were easy, it would have been done! But it’s not. Discussions dug into deeper questions about HOW change can be brought about and the implications of this for action in Bangladesh.

The participatory and dynamic workshop brought together policymakers, researchers, youth leaders, key UN organisations and members of the private sector. The workshop served two purposes, first to help clarify directions for the Action Plan, and secondly, to take forward the work on using foresight to help drive food systems change.

Discussion during the workshop focused on the five commitment pathways:

- Nourish all people

- Boost Nature-based Solutions

- Advance Equitable Livelihoods, Decent Work & Empowered Communities

- Build Resilience to Vulnerabilities, Shocks and Stresses and

- Accelerating the Means of Implementation

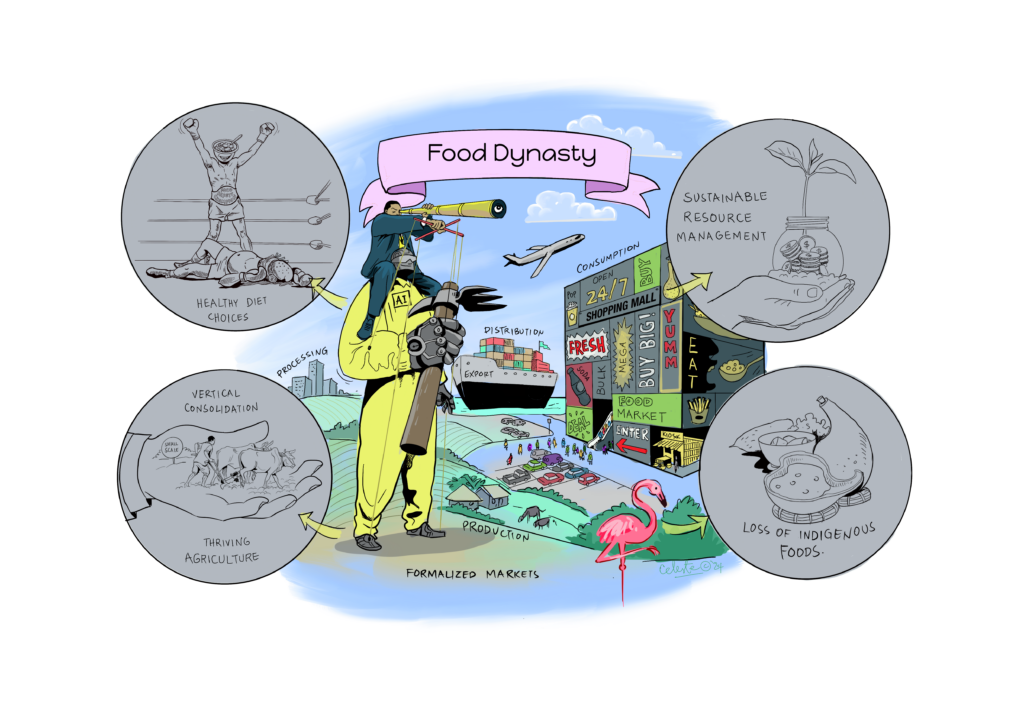

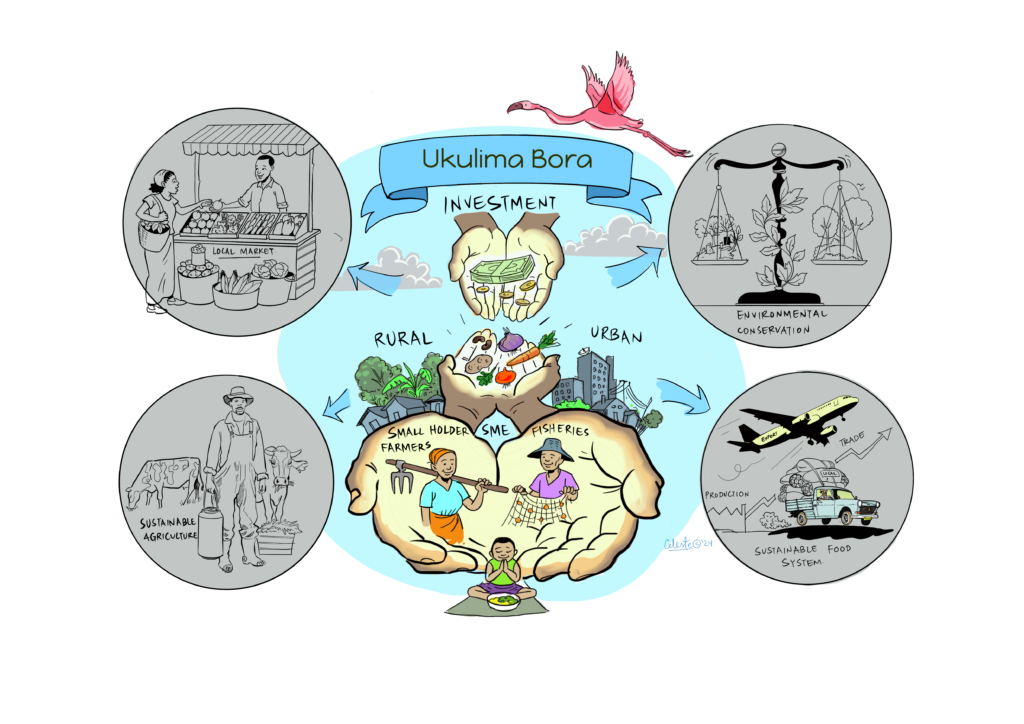

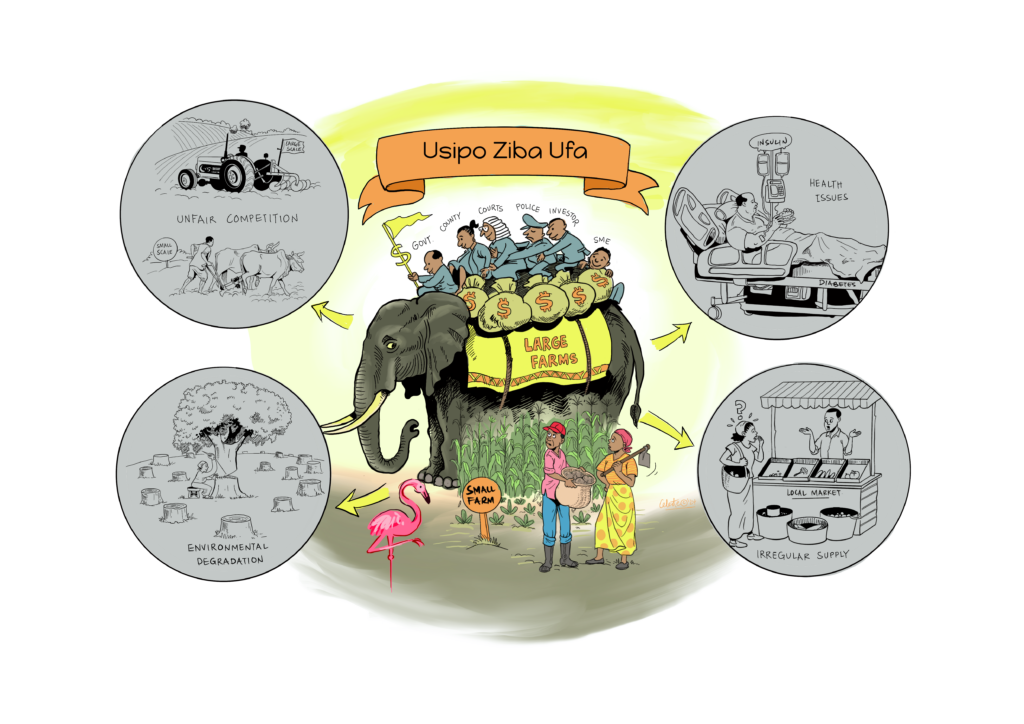

Validating scenarios for the future of food systems in Bangladesh

It was great to engage in discussions around four visual future scenarios. These were developed using rich pictures during a lively multistakeholder event in June earlier this year. Future scenarios are an excellent way to open discussions around what different stakeholders see as a desirable future. Interestingly, these do not always align as the implications would vary depending on what outcomes you’re seeking. At the end of the day, a poor farmer will desire different things when compared to a corrupt businessman!

The scenarios displayed different outcomes based on these uncertainties:

Equity – Would there be high or low levels of equity?

Climate resilience – we all know that climate change is happening, but whether Bangladesh will have high or low climate resilience is definitely in question

Healthy food consumption – Would people in Bangladesh be eating traditional diets or would they follow a diet that resembles something like a North American diet, something seen in many parts of the world.

Business structure – would Bangladesh have a diversified or consolidated business structure, dominated by a few large conglomerates

Creatively naming these scenarios helps convey the messages. So we had a fun exchange where groups came up with poetic Bangladeshi names to better describe the scenarios. Part of the validation will be to update these, helping spur action towards the most desired and away from the least desired future.

Unpacking five critical issues

Key issues blocking progress towards food systems change in Bangladesh relate to:

- The cost of a healthy diet in addressing malnutrition

- Climate resilience

- The role of social protection programmes in shaping food systems change

- Fruit and vegetable production

- Land use change and dietary patterns

These key themes were the result of a longer participatory process that emerged from the food systems map of Bangladesh. Diving into these topics, FoSTr’s five research partners shared their work on the key trends, challenges, and opportunities within each theme. Exploring these themes using a future lens can help clarify desired directions of change.

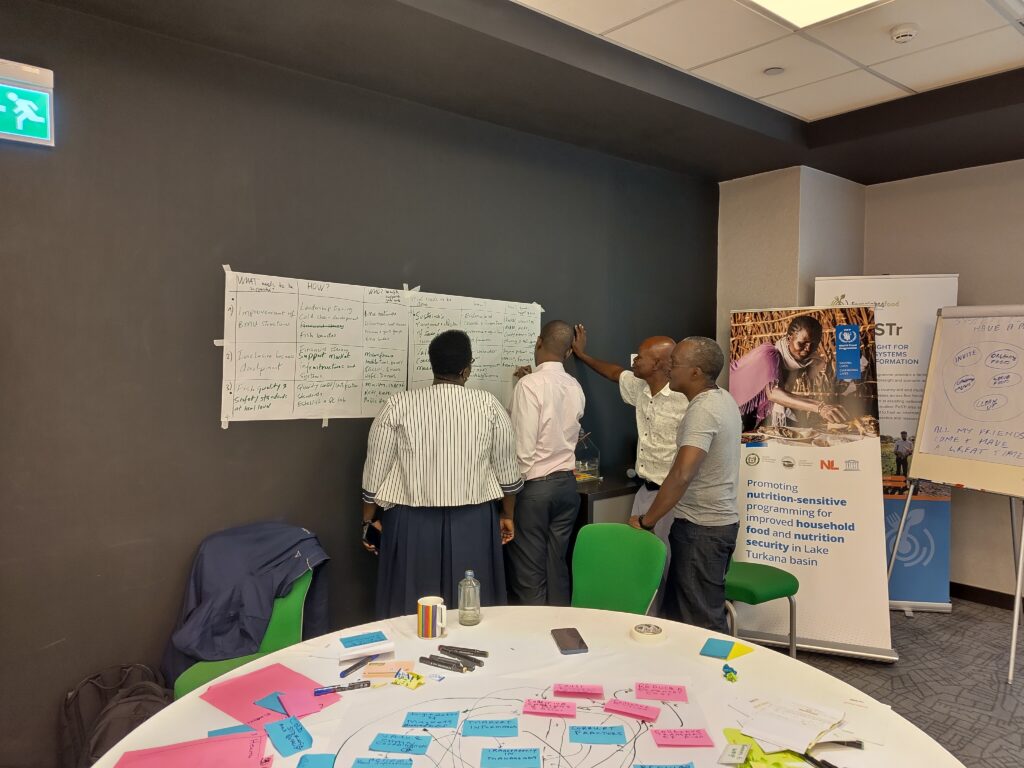

The power of causal loop mapping

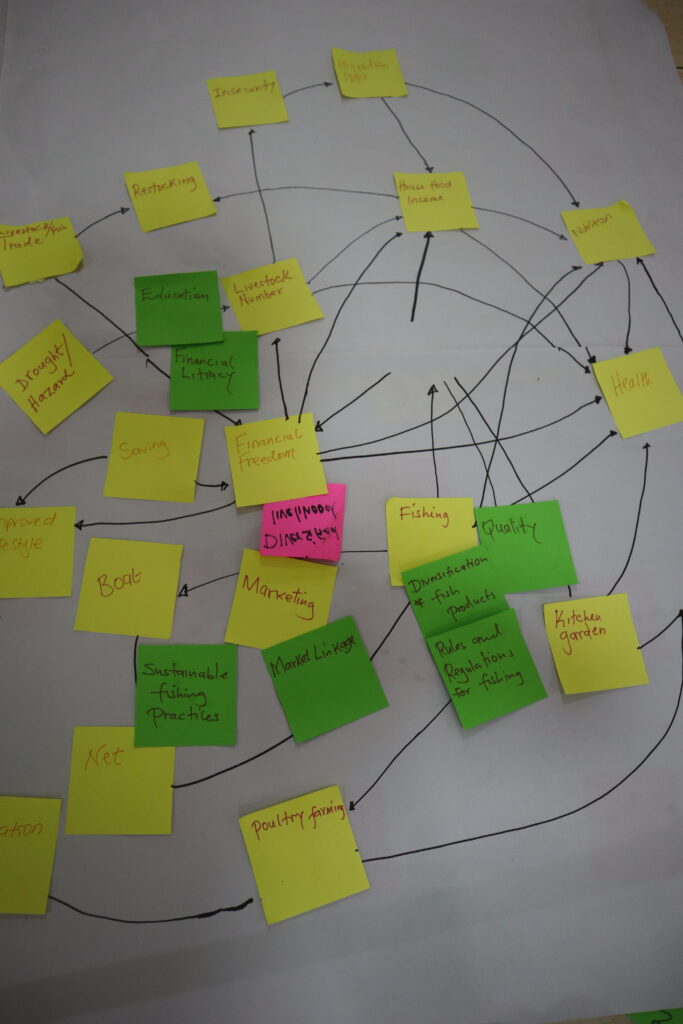

How often do you get policymakers, youth and researchers around one table, heavily immersed in discussion using sticky notes and flip charts? My response: not often enough! This combination of actors is rarely seen but proves oh so valuable in uncovering insights previously hidden from each sector. The tool casual loop mapping, may be familiar to some. It’s a systems thinking tool where the interconnections between elements are mapped and the direction of causality identified. It’s a great way to map out the elements within a system and identify levers of change – small actions that lead to a large impact. For each of the commitment pathways, this casual loop mapping was performed. Insights like forming alliances between farmers and entrepreneurs to boost sustainable farming practices, or using the power of advertising to improve healthy food consumption and inspire healthy lifestyles were uncovered.

Reflections

Whilst having many people come together who don’t usually converse – the so-called ‘breaking the siloes’ is a huge achievement in itself, the task of writing yet another policy document looms above our heads. Everyone in the room has appeared here for a reason – which I hope is to create the change we need, a future that we all desire. After such positive discussions and recognition that we need to act – and act now, the fear I have is we will all fall into the same trap. The trap of being consumed by our busy agendas and becoming frustrated that yet another policy document has to be produced. Leading to un-actionable and hugely categorised actions. We don’t want this Plan of Action to become another document that has great suggestions but continues to lack the HOW. Let us think about how will these actions be implemented.

Foresight helps us to keep the bigger picture in mind, where do we want to go and where do we want to be in the future? Let’s use this thinking to help us prioritise and select key activities to implement. Working together to do so.

By Jim Woodhill, Lead Foresight4Food Initiative

Last week, I had the wonderful opportunity to support a regional training workshop on foresight for systems change in Nepal, in collaboration with the International Centre for Integrated Mountain Development (ICIMOD).

The workshop brought together a group of 35 development practitioners from across the Hindu Kush Himalaya region, including participants from Nepal, Bangladesh, Bhutan, India, and Pakistan. The focus was on how to use foresight to help tackle the big regional issues of climate adaptation, creating diversified and resilient livelihoods in mountain areas, migration, and disaster preparedness.

ICIMOD invited Foresight4Food to collaborate in facilitating the training, using Foresight4Food’s Framework of foresight for systems change following the organization’s participation in a similar leaders capacity development workshop held in Africa in 2023 (see report and video here) and Foresight4Food’s 4th Global Meeting in Bangladesh.

The Nepal event was a good chance to build on Foresight4Food’s capacity development experience in Kenya, Jordan, Bangladesh, and Uganda. These are focus countries for the Foresight for Food Systems Transformation (FoSTr) programme, supported by the International Fund for Agricultural Development with funding from the Dutch Government.

While food issues were only part of the focus of the workshop, the issues raised during the week yet again highlighted that the way food is consumed and produced is central to all development issues. Migration, climate adaptation, equitable livelihoods and managing disasters are all interconnected with agrifood systems.

What was covered in the training workshop?

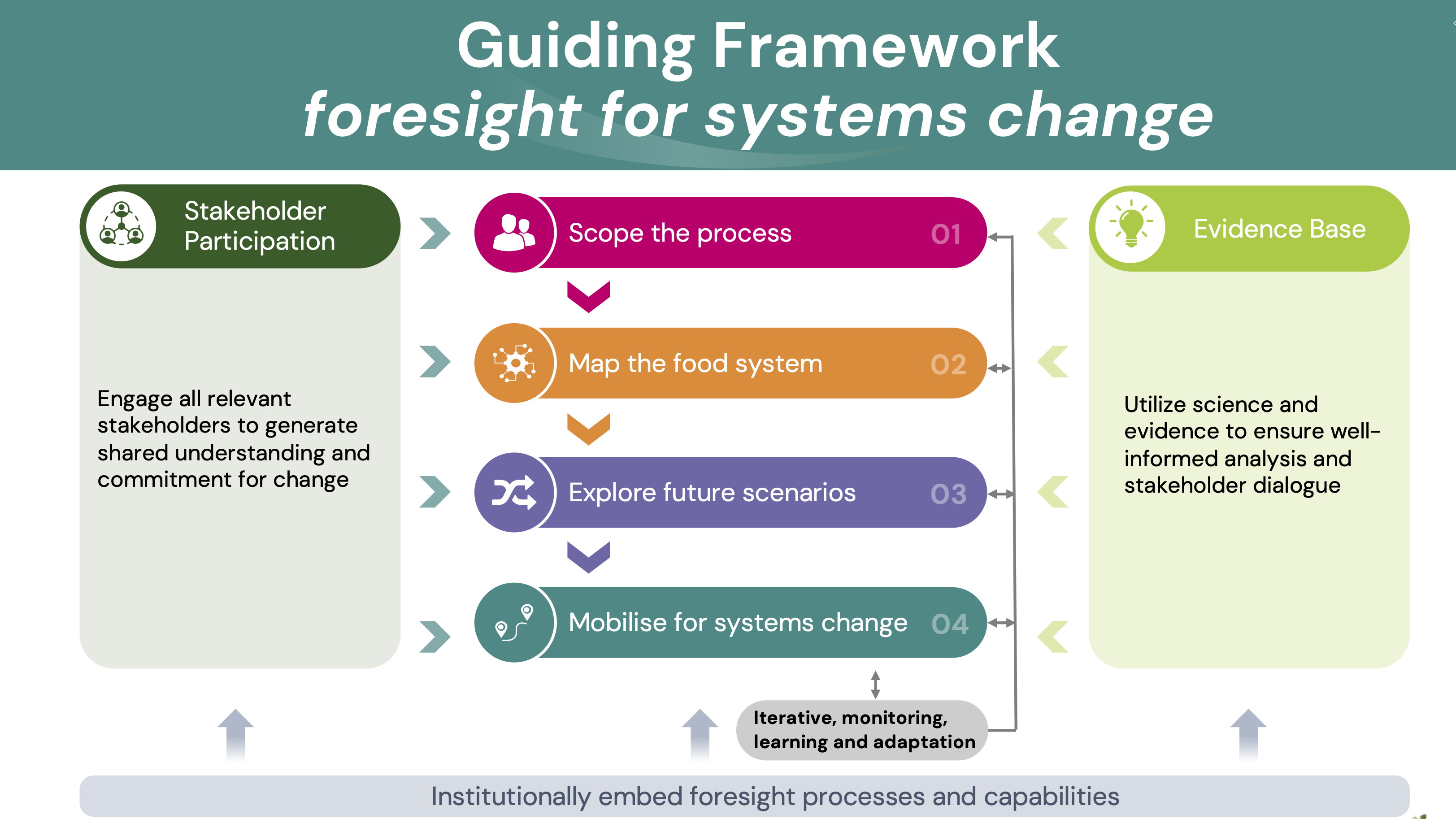

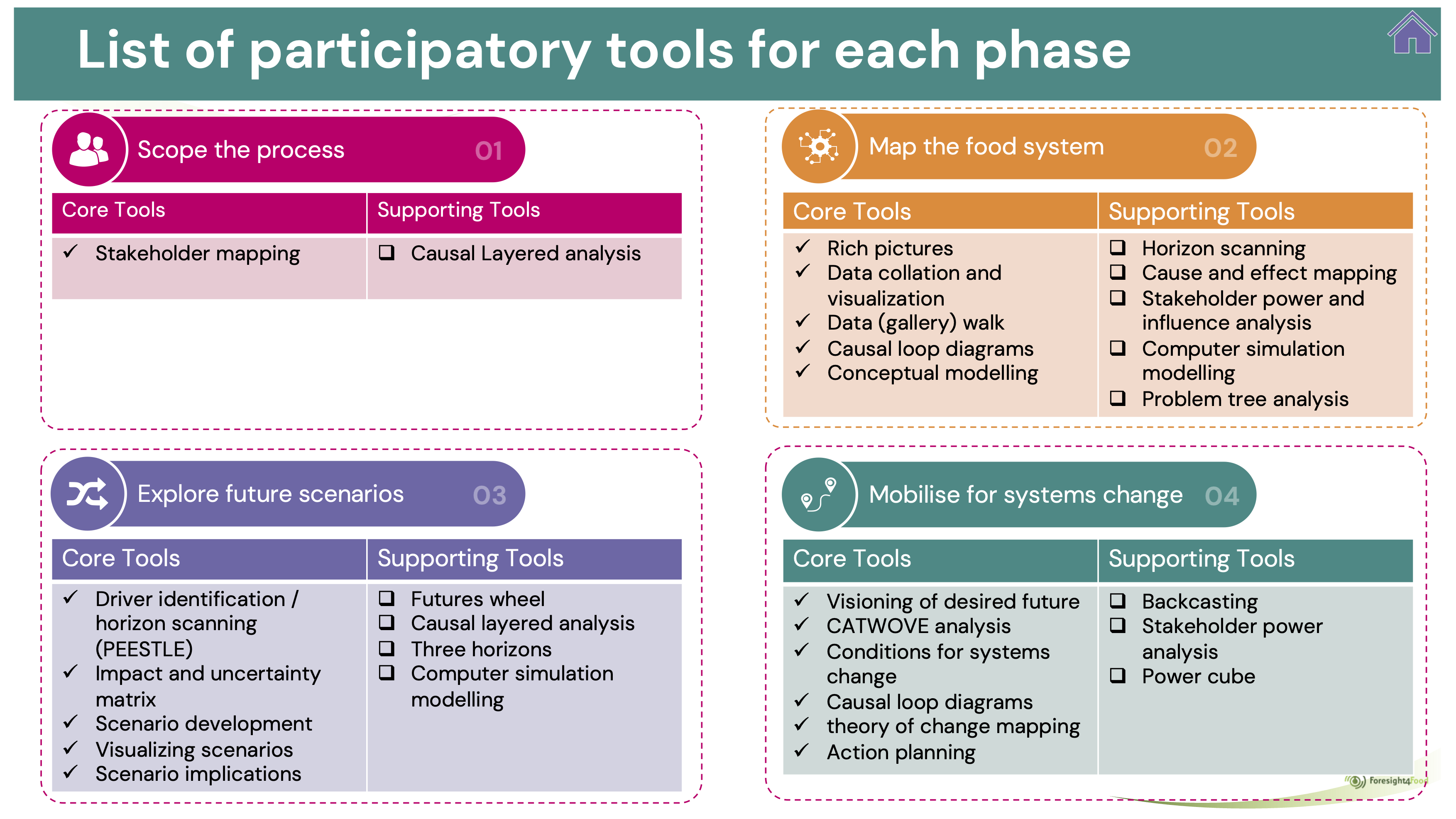

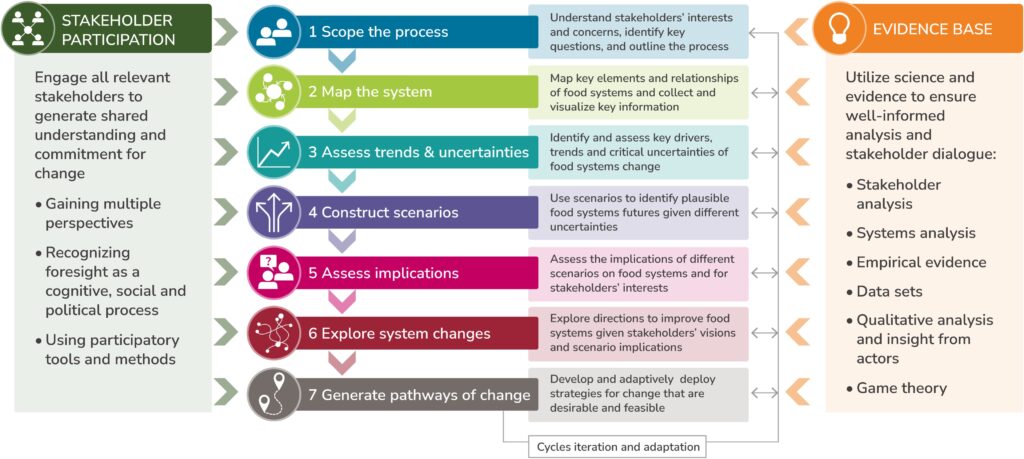

During the week, the participants worked through the four main phases of the Foresight4Food Framework:

- Scoping the process

- Mapping the system

- Exploring future scenarios

- Mobilising for systems change

For each phase, participants were introduced to background concepts and theory, and relevant participatory foresight and systems thinking tools. Rich pictures, drawn by participants to illustrate the whole system, is always a favourite. Other tools we worked with included horizon scanning of future trends and uncertainties (guided by the PEESTLE acronym), data exploration, causal loop diagrams, scenario development, visioning, back casting and conceptual modelling of systems.

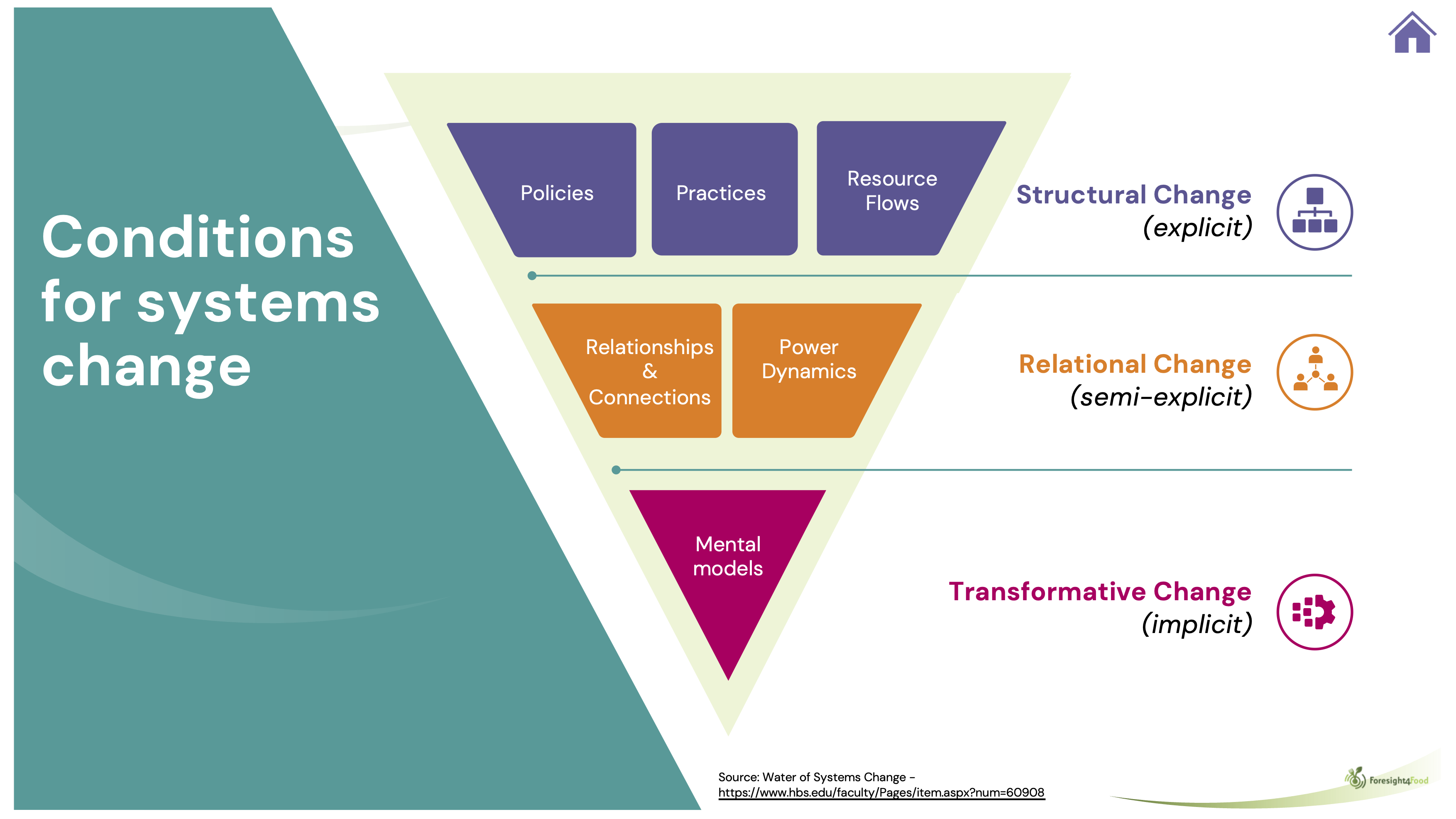

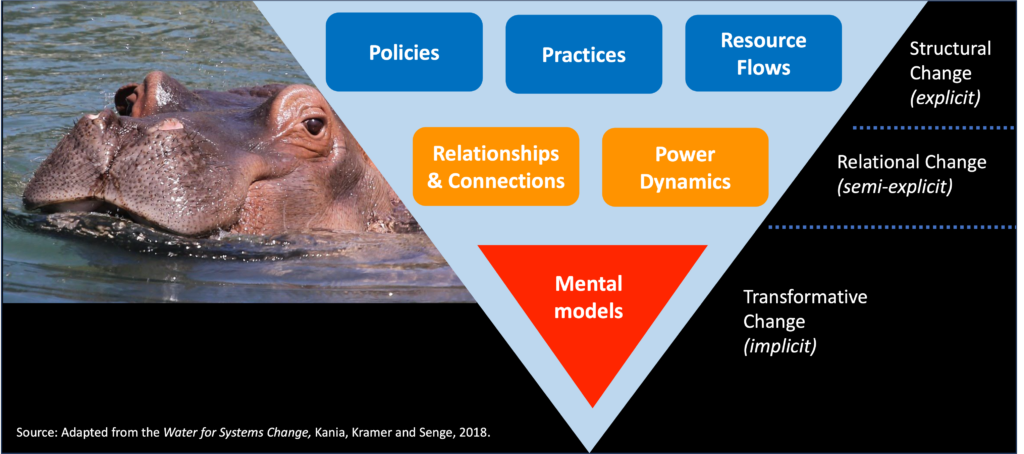

We discussed how change happens in complex adaptive (human) systems. The systems change “triangle” helped thinking about the role that mindsets and different forms of social and political power play in enabling or constraining change. The importance of bringing a gender equity and social inclusion (GESI) perspective to foresight was highlighted.

Participants applied their learning directly to the issues of climate adaptation, pastoralism, migration, and disaster preparedness.

The need for foresight

The global polycrisis is having a big impact on the Himalayas. The confluence of climate change, conflict, disease risk, inequality, biodiversity loss and geopolitical instability are bringing high levels of uncertainty and turbulence for citizens, businesses and governments across the region. For example, the melting of glaciers and the impact of extreme rainfall has profound implications for life in the mountains as well as for the billions of people who depend on the river systems that flow out of the Himalayas.

The Himalayas sit in the middle of a region with significant political tensions and shifting powers, which has major implications for the collaborative governance needed to effectively respond.

Foresight for systems change can help communities, organisations and governments better anticipate future risks and reimagine the future, so as to be more adaptive and resilient.

Thinking ‘out of the box’ – Foresight or “shortsight”?

Challenging discussions emerged during the week about how to ensure that foresight processes don’t just end up with the same old stuff – “old wine in new bottles”. To avoid this, we explored the need for “out of the box” thinking. This means looking for weak signals that might indicate a coming disruption, challenging assumptions about the future, bringing different perspectives to the table, using creative techniques to imagine radically different futures, and using the insights of “futurists”. A comprehensive horizon scanning process that explores mega-trends, trends, weak signals, critical uncertainties and wildcards helps to ensure foresight rather than “shortsight”.

Beyond tokenistic stakeholder participation

Across the Himalayas, it is local communities, local government and local businesses who must cope with the direct impact of floods, extreme heat, price fluctuations or disease outbreaks. Time and again participants returned to the importance of engaging local stakeholders to understand the challenges, and to generate pathways for greater resilience.

The discussion led to a shared understanding that this kind of participation from stakeholders requires genuine and open dialogue, made possible by using participatory workshop tools and techniques. However, all too often stakeholder engagement processes, when they do happen, fall back to formalised meeting structures, with speeches and presentations by “important” people, with little or no use of the sort of participatory analysis and dialogues tools participants engaged in during the training week. Advocating for effective, participatory and transformative stakeholder engagement processes is an obvious role for ICIMOD.

Institutional barriers to foresight and systemic practice

At the end of the week participants explored how to use foresight and systems thinking and practice in their own working context. Then some of the realities hit home.

Funders and donors often still force very linear, short-term and inflexible modes of programme design and management. Policymakers struggle to work effectively in a cross-ministerial way. People who see themselves as “senior” resist rolling up their sleeves and actively engaging in participatory processes with other stakeholders. Response strategies often stick to the safe space of technical analysis and technical solutions ignoring how mindsets and power structures block transformational change.

These are challenges that organisations like ICIMOD and initiatives like Foresight4Food need to help tackle if foresight is to have a real impact on policy and local action.

Cultivating a cadre of foresight and systems change practitioners

Participants recognised there is a limited number of practitioners/professionals across the region who have the knowledge, skills and experience to effectively design and facilitate foresight and systems change processes. A big effort is needed to create a cadre of practitioners who do have these capabilities.

To tackle this gap, governments can develop foresight units, universities could make futures literacy and systems thinking part of their curriculum, and development organisations need to in invest more in such human capabilities.

Way forward

On the last day of the workshop, the “collective intelligence” of participants was used to start framing a new horizon scan for the region that could follow up on the highly influential 2019 HIMAP report on the region.

Participants left with many practical ideas of how they could apply the foresight thinking and tools directly to their work.

For ICIMOD and Foresight4Food hopefully, this was just the start of collaborating to strengthen regional capacities for foresight.

The energy and commitment of participants were astounding, especially given long days of challenging discussions.

All in all, it was a super inspiring week – giving hope that with committed people like those in the workshop, supported by organisations like ICIMOD, we can together create a more resilient and equitable future.

By Bram Peters

The Foresight4Food FoSTr team has just returned from an active and productive trip to Kenya, despite the challenging political situation in the country. From our perspective, this highlights the need to adapt to turbulence and to use foresight to build resilience for Kenya’s food system.

From June 19 to 26, together with my team members including Jim Woodhill, Herman Brouwer, and Wangeci Gitata-Kiriga we conducted a range of food systems foresight workshops in Nairobi and Nakuru with a wide range of national food systems stakeholders. Here is a brief update on the action.

Navigating turbulence

On the morning of June 19, Foresight4Food, together with partners ILRI–CGIAR, Results for Africa Initiative and University of Nairobi, organised two sessions in Nairobi. The interactive breakfast session was all about ‘Navigating agri-business in turbulent futures’. The session was co-hosted by IFAD Kenya and was attended by a range of private sector associations, business support services, innovation facilitators and impact investors.

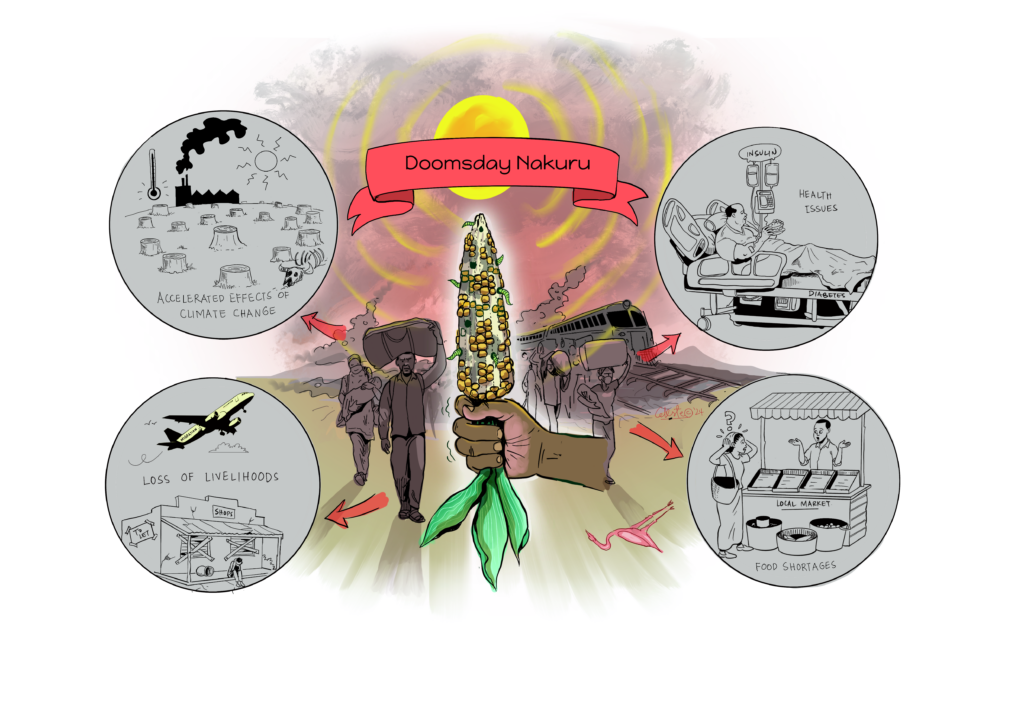

The focus of the meeting was to introduce the topic of foresight in relation to agribusiness in Kenya, share some of the scenarios that were developed in the context of Nakuru, and discuss the implications of different futures of the food system. Participants were shown five different scenarios of how the food system might look in 2040 in Nakuru and were invited to think through and discuss the implications of these scenarios.

With a strong presence and involvement of leaders from various private sector associations such as the Agriculture Sector Network (ASNET) of the Kenya Private Sector Alliance, the discussion invited stakeholders to reflect not only on trends and uncertainties emerging in Kenya, but also how their own businesses are preparing for the future.

Supporting the pathways for food system transformation

In the afternoon of June 19, the FoSTr team organised a national update session on the progress of FoSTr since June 2023. The session was attended by many individuals from the morning session, as well as representatives from government, civil society and research organisations. The FoSTr team presented the latest updates, including the launch of a ‘Kenya Food Systems Mapping Report’, and with a collection of scenarios for the Nakuru food system.

With a special presentation by the Ministry of Agriculture and the Food Systems Technical Working Group and special remarks from IFAD on the 3FS tool, it was discussed how a wide range of ecosystem support initiatives are buttressing the national food systems transformation pathways in Kenya. The approach by Foresight4Food to engage with two counties, Nakuru and Marsabit, and to build on Bottom-up initiatives showed how our approach complements the ongoing national-level initiatives.

Systemic Theory of Change

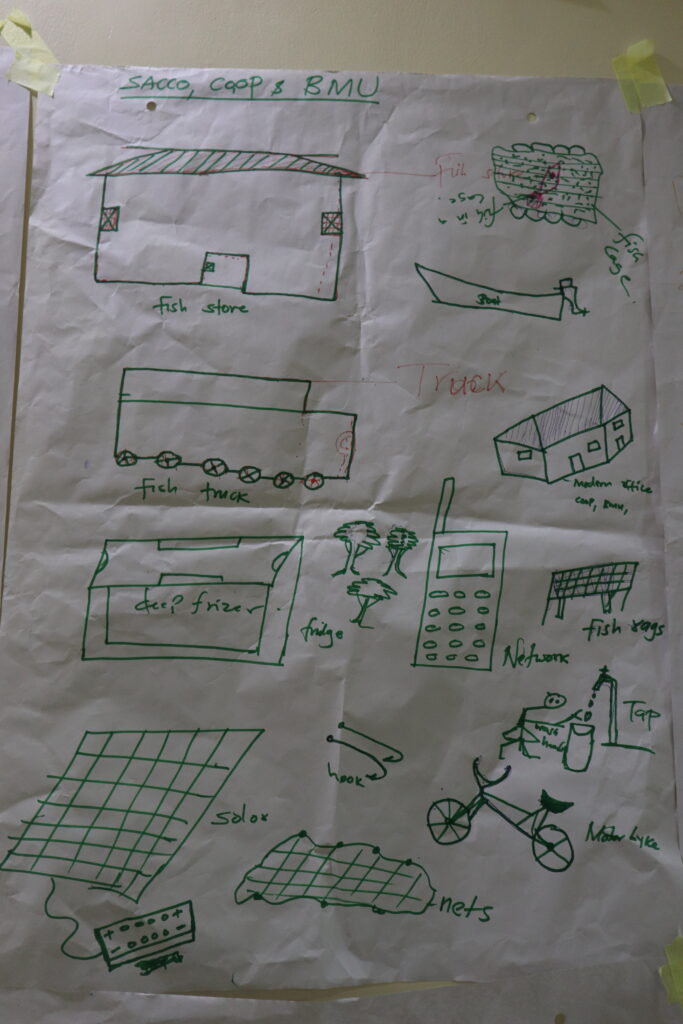

From June 19 to 21, the Foresight4Food FoSTr team facilitated a 3-day workshop for the inception phase of the new Netherlands-funded, World Food Programme and UNESCO on ‘Sustainably Unlocking the Potential of Lake Turkana. Stakeholder representatives from the Lake Turkana region (both on the Marsabit and Turkana sides of the lake) gathered in Nairobi to engage in a shared analysis of the complex food system and co-create the high-level focus of the programme.

The Turkana Lake food system is highly complex, with high food insecurity, vulnerability to climate change and conflict, and many cultural dynamics around pastoralist and fisheries livelihoods. Finding market opportunities and strengthening resilience is not easy, and requires a different way of working. Using the Foresight4Food approach, and building on 6 scenarios that were developed in previous workshops in Marsabit and Turkana, stakeholders explored what might need to be done to understand systemic risks and how lasting opportunities can be triggered.

Preparing a Systemic ToC is all about analysing the context, articulating the transformations needed in light of various future scenarios, and developing the building blocks for action. The building blocks include pathways, processes and partnerships. Through many interactive discussions and exercises, the stakeholders conducted value chain mapping of the fish value chain, CATWOVE for articulating systemic change narratives, and Causal Loop Mapping.

Manifesto for Change for the Nakuru Food System

On June 24 and 25, the FoSTr team including partners ILRI-CGIAR, Results for Africa Initiative and University of Nairobi once again visited Nakuru, now to explore systemic change pathways. As we already noted from previous workshops, the food system of Nakuru County is full of potential, as Nakuru’s natural resources are rich and a wide range of agricultural value chains are represented. However, challenges related to food and nutrition security and environmental sustainability exist. Trends of climate change, unhealthy diets and land fragmentation are appearing. The future holds many uncertainties. In order to future-proof the food system, it is urgent that investments are made to further enhance the resilience and sustainability of food and agriculture in Nakuru.

Since November 2023, a diverse group of more than 40 different stakeholders from Nakuru county have been coming together to consider the future of food system, supported by researchers and facilitators of Foresight4Food. This inclusive group looked at the challenges and opportunities for food and agriculture today and how they might evolve in 10-15 years. Food system analysis, an assessment of drivers and trends relevant to Nakuru, and 5 scenarios were developed by this group.

During these two days, stakeholders from Nakuru engaged in scenario interpretation and Causal Loop diagramming to come up with key pathways to kickstart food system transformation in Nakuru. These outputs culminated in a Manifesto for Change: a vision for the desired future for Nakuru’s food system and a range of possible pathways that can set us in that direction, while preparing us for a range of uncertainties. The Manifesto calls upon all stakeholders to join and align their actions, and intensify collaboration to transform Nakuru’s food system so that it can feed its people nutritiously; advance economic development; restore balance with nature; grow in-county revenue and eventually GDP growth for Kenya.

By Bram Peters – Food Systems Programme Facilitator, Foresight4Food

In the north of Kenya, on the border with Ethiopia, the landscape is expansive and dry. Pastoralism is the main source of livelihood, but to the west of this landscape is Lake Turkana, one of the largest saline desert lakes of the world. Here communities engage, some productively and others reluctantly and out of desperation, in fishing.

In March 2024, the Foresight4Food FoSTr team traveled to the fascinating Kenyan county of Marsabit to facilitate a multi-stakeholder forum to support the co-creation of the new ‘Sustainably Unlocking the Economic Potential of Lake Turkana’ programme.

In Marsabit, stakeholders from around the Turkana Lake, including fishers, traders, service providers, county government technical officers, and non-governmental organizations, came together to analyze the context and co-create future scenarios and intervention areas for a new WFP and UNESCO programme, funded by the Embassy of the Kingdom of the Netherlands.

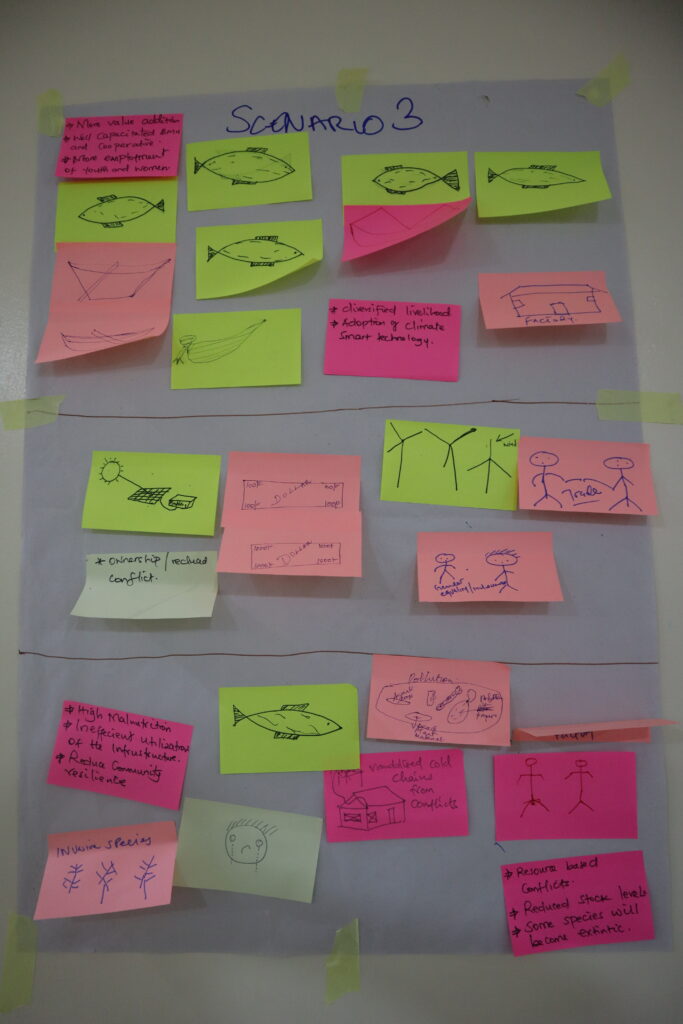

Together with the World Food Programme and the World Food Programme Innovation team, the FoSTr team held a highly interactive and productive three-day workshop. As most stakeholders mainly spoke Kiswahili, we switched to short presentations with much emphasis on interactive group work. On the first day, the workshop focused on contextual understanding of the Lake Turkana food system as well as the Marsabit county livelihoods, using the Rich Picture mapping exercise. Participants together drew the food system, the geography of the lake, but also the stakeholders, activities, key relations and dynamics.

On the second day, the groups presented their deep knowledge of the context to each other and elaborated on this. Workshop participants tackled key trends shaping the food and livelihoods system: groups discussed how various themes (for example: lake water levels, fish stocks to income sources, conflict, and education) changed over time and what they expect to happen 10 years into the future. Important in this discussion is their analysis of what driving issues would influence change in the future.

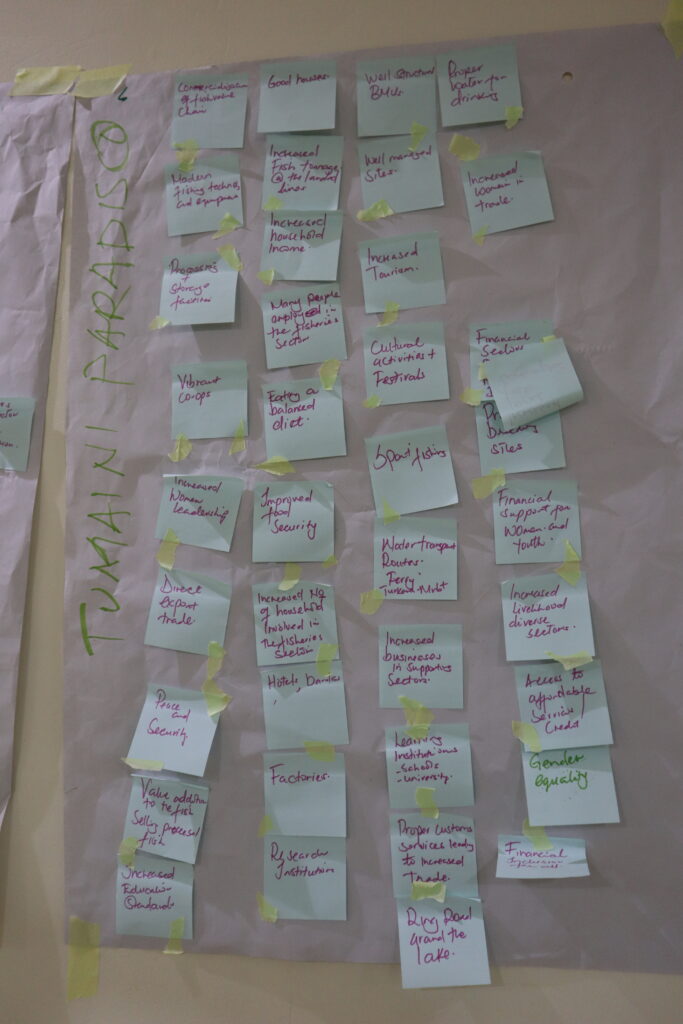

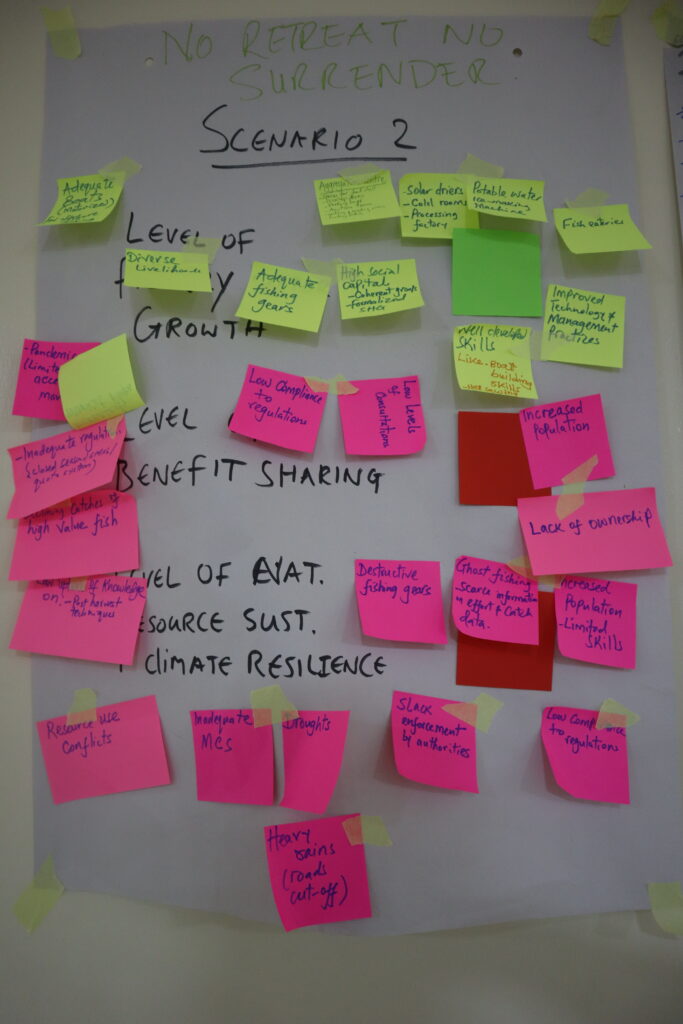

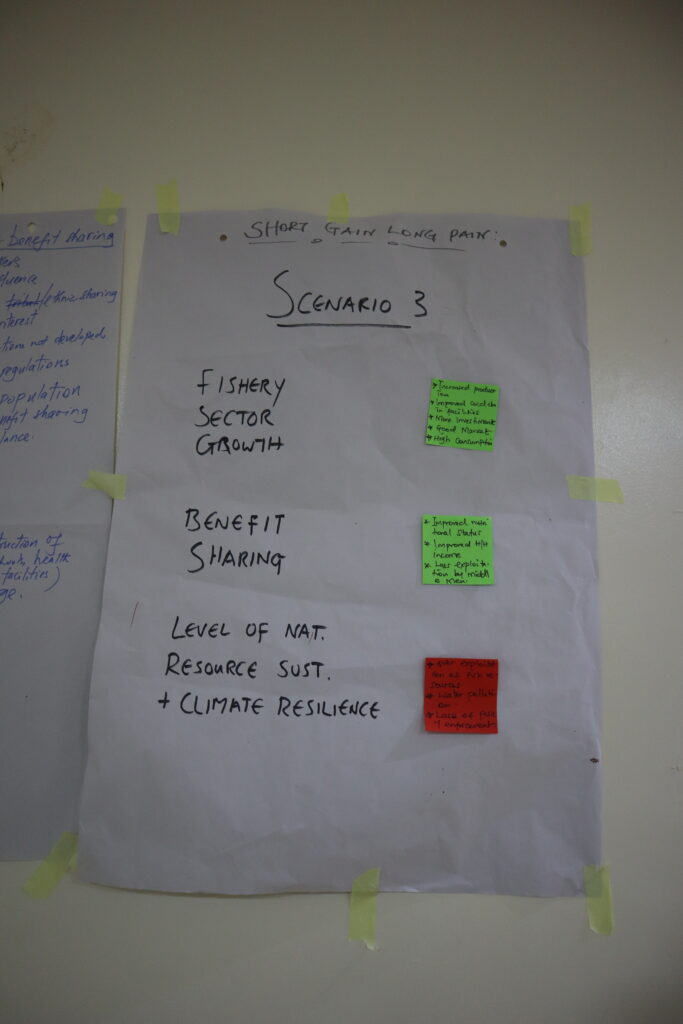

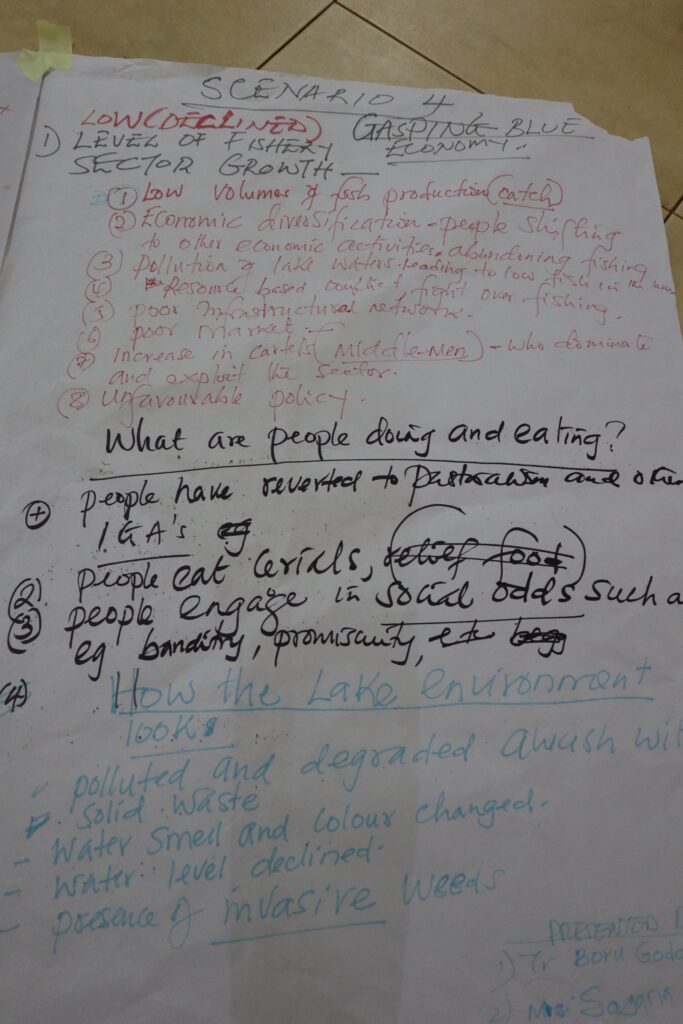

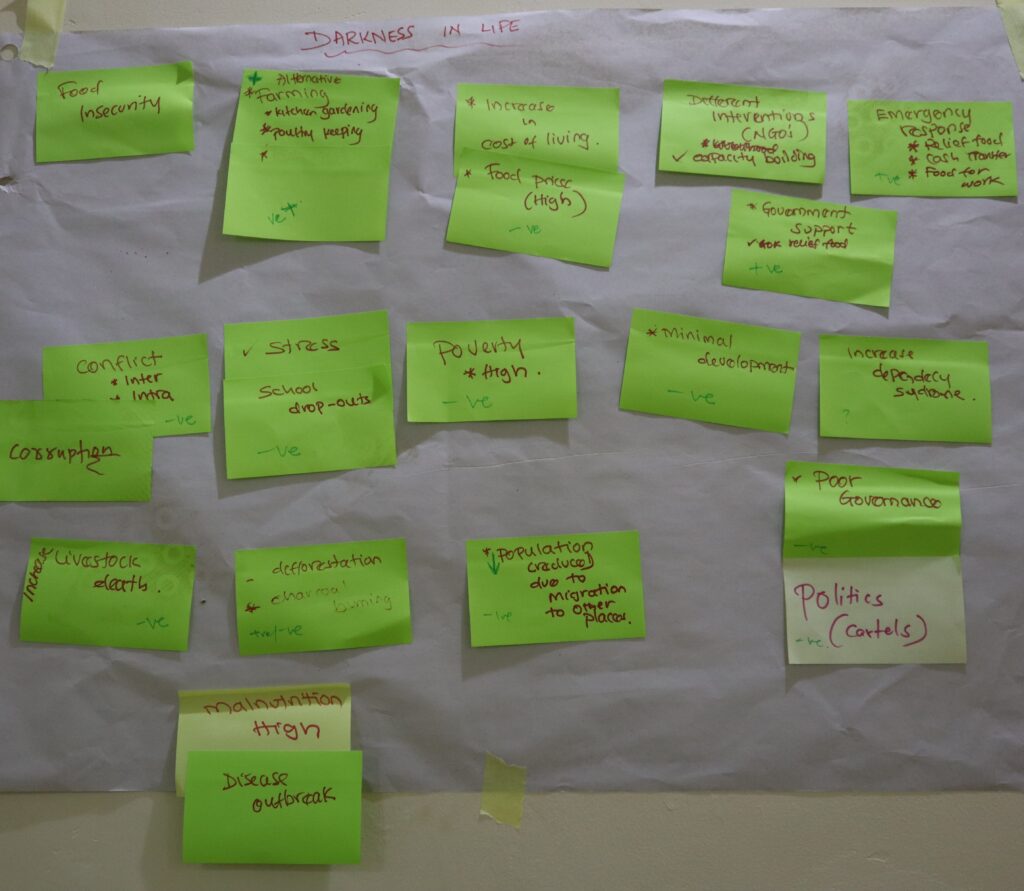

5 scenarios were created for the future regarding the fisheries sector and supporting livelihoods, as well as an in-depth discussion on key entry points for intervention in the system. These scenarios had names that described these futures succinctly:

- ‘Tumaini Paradiso’, a future with a growing fishing sector, inclusive benefit sharing and sustainable natural resource management;

- ‘No retreat, no surrender’, a situation in which the benefits of a growing fisheries sector are controlled by a few;

- ‘Short gain, long pain’, a scenario where the fisheries sector grows and livelihoods improve around the lake, but the environment is not maintained;

- ‘Gasping blue economy but others rise’, is a future where the fisheries sector remains marginal for communities, but other sectors are developed that also contribute to inclusive development and environmental sustainability

- ‘Darkness in life’, a bleak outlook where none of the envisioned sustainable economic development around the lake delivers and where climate resilience is low, and conflict is rife.

Different stakeholders participating in the workshop had different opinions on the likelihood of certain scenarios emerging. Some imagined the situation worsening, while a few viewed the future more positively. These reflections clearly showed a combination of outlook of participants as well as the signals they interpret from the current situation and the trends seen now. Interestingly, none of the stakeholders felt the ‘Paradiso’ scenario was likely, showing that the programme needs to be modest in its systemic ambitions, but also be ready to do things very differently. These scenarios showed what could become a very relevant frame of reference to the stakeholders as well as the programme implementors.

On the last day of the workshop, participants explored a common vision for the future, and how the food system is currently working. This led stakeholders to have a first try at exploring what is needed to change that system toward the common vision.

At the end of the workshop, I felt highly positive about these fruitful discussions that enabled participants to think about what might happen to the Marsabit food system in the years to come, and what factors would influence these changes. In addition to that, the insights gathered through the multi-stakeholder forum are expected to not only support the inception phase of the programme but will also support multi-stakeholder engagement throughout the programme.

The Foresight4Food FoSTr team will continue to support the World Food Programme team in realizing the ‘Sustainably Unlocking the Economic Potential of Lake Turkana’ programme inception phase. A follow-up workshop will take place in Turkana County from March 25 to 28, with stakeholders from that side of Lake Turkana.

By Jim Woodhill, Foresight4Food Initiative Lead

Last month (November 2023) I had the wonderful experience of engaging with over fifty young leaders from across Africa, joined by colleagues from Bangladesh, Nepal, and Jordan. We had all gathered in Naivasha, Kenya, to explore how skills in facilitating foresight can be used to help bring about food systems transformation.

The fascinating work these young leaders are involved in and their deep interest in understanding how to be more effective change-makers was truly inspiring. It was encouraging to see how valuable they found the foresight for the food systems change framework and the associated set of participatory tools for engaging stakeholders.

Participants all came with projects from their own countries where they are keen to use foresight and systems thinking to help facilitate change in food systems by bringing together different stakeholders. The participants were from diverse backgrounds representing policy, the private sector, NGOs, and academia.

A Guiding Framework: During the workshop we introduced participants to an overall guiding framework for facilitating foresight for food systems change. A range of participatory tools were used for systems analysis, development of future scenarios and exploring systemic interventions. To bring reality into the workshop, the Kenya horticulture sector was used as a case study for the foresight analysis. Participants spent a day visiting horticulture farms, packing and processing facilities and the local market. They explored with local stakeholders how they saw the future for the horticulture sector and the issues that “keep them awake at night”.

Visualising the system: The workshop was highly interactive with participants practicing in the facilitation of a range of participatory tools which can be used to bring stakeholders into dialogue around systems change. One of my favourite participatory tools “rich picturing”, which enables a diverse group of stakeholders to develop a shared understanding of a system by drawing it, was found by participants to be especially powerful.

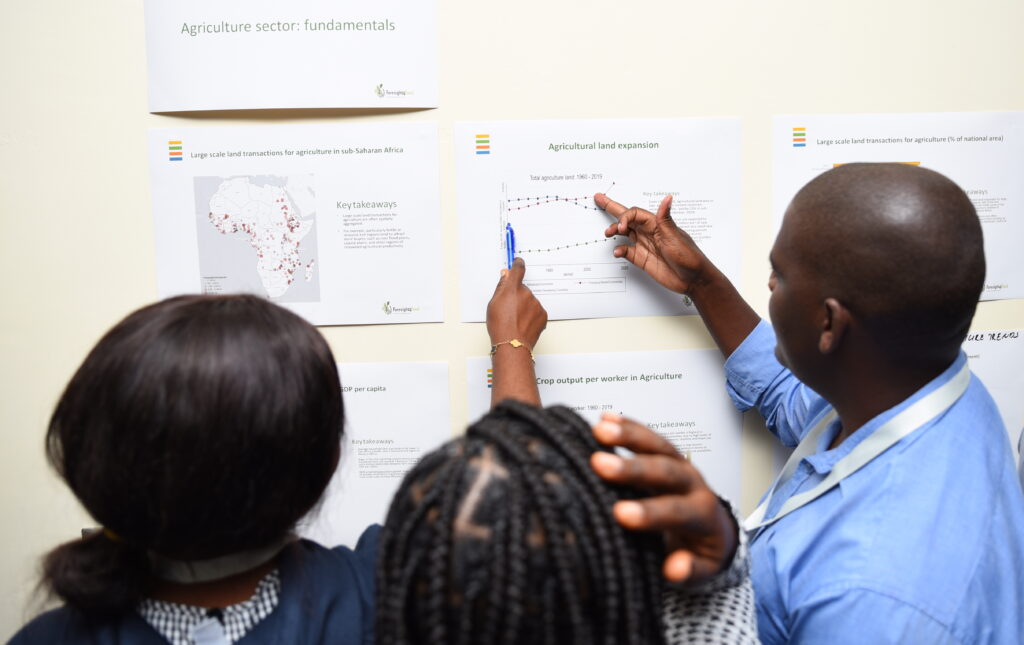

Data-driven dialogue: To go deeper into the systems analysis it is valuable for stakeholders to explore the available data on key drivers and trends. Over 100 graphs visualizing key data points related to the Kenya horticulture sector and food systems at national, continental, and global scales were collated and posted around the walls. The participants then explored this data in groups of three and discussed its implications and how it perhaps challenged their existing assumptions.

Exploring the future using scenarios: Central to the foresight approach is developing a range of different plausible future scenarios (generally with a 10 to 30-year horizon) for how the system might evolve given critical uncertainties. Workshop participants did this for the horticulture sector, looking at factors such as how diets might change in the future, regional and global trading relations, severity of climate change, and the enabling policy environment for small-scale producers and the small- and medium-scale enterprises (SME) sector. The scenarios help to identify future risks and opportunities for different stakeholder groups and society at large. They also help to unlock creative thinking about how to “nudge” systems towards more desirable futures and away from less desirable ones.

The deeper issues of systems change: It is easy to talk about systems change. In reality trying to change systems bumps into all the difficult issues of vested interests, power relations, ideologies, and deeply held cultural beliefs. On top of this human and natural systems are complex and adaptive and behave in self-organising, dynamic, and often unpredictable ways. It doesn’t mean you can’t intervene to try and bring positive change. But it does mean that top-down, linear, and mechanistic models of change generally don’t work. The workshop engaged participants in deep and challenging discussions about what it means to be a leader of systems change. This included the need to be adaptive, how to create alliances for disrupting existing power relations, the importance of building relations between diverse stakeholders, and the importance of patience. Systems change often requires taking time to build the foundations for change without being able to know when circumstances might suddenly unlock opportunities for big steps forward.

Identifying directions for change and intervention options: Developing directions and pathways for systems change is the most difficult and challenging part of the foresight for systems change process. It is highly context-specific and requires a deep insight into the political economy of the situation. Cause and effect mapping, theory of change thinking, and causal loop analysis can all help in identifying opportunities for intervening which could help to drive systems change in desired directions. Bringing change will often require an integrated approach to technological, institutional and political innovation. During the workshop causal loop diagrams were used to explore possible entry points for shifting horticulture systems in ways that could improve health, livelihoods and the environment.

New friends, new networks and big ambitions: After an intense week of learning and sharing participants left inspired to apply the foresight approach back in their own work environment. New friends were made and there were clear calls to find mechanisms to support ongoing networking and peer support.

Many thanks to the facilitation and support team who made a fantastic week possible, Gosia McFarlane, Marie Parramon-Gurney, Kristin Muthui, Bram Peters, Joost Guijt, Riti Herman Mostert, and Abdulrazak Ibrahim. The event was made possible by support from the Mastercard Foundation.

More information about the Foresight4Food Framework of Foresight for Food Systems Change can be found on our website, and an updated approach paper will be published in January 2024.

An update on a two-part IFSTAL training course held at Makerere University

Bring together 26 individuals drawn from university students, academics and professionals working across the food sector in Uganda and what do you have? The kernel of a powerful network to help tackle malnutrition in country in all its varied forms.

Equipping participants with the skills to become food systems thinkers was the aim of a two-part training course delivered by Interdisciplinary Food System Teaching and Learning’ programme (IFSTAL) in collaboration with Makerere University, Kampala.

Malnutrition is the new normal

Despite the emergence of food systems approaches to address food insecurity in the content of other SDGs, malnutrition in Africa is becoming the ‘new normal’. This is down to a lack of skills across the policy and practice workforce to tackle food system challenges in the necessary integrated manner.

Fixing systemic problems across the food sector while enhancing livelihoods needs interdisciplinary systems thinkers. The lack of sufficient food systems training – and hence skills in the workforce – is a major impediment. This is partly due to university curricula being ill-equipped to provide the necessary interdisciplinary food systems training for students who will move on into the food sector, and partly due to weak networking across the sector itself.

Creating skills for change

Generously supported with a grant from the Open Society Foundations, the course was planned in two parts. Part 1 held in January 2020, covered basic food systems approaches. Giving participants time to reflect on the first part in their work contexts, Part 2 was designed to follow three months later, covering system change and foresight. Covid-19 intervened, which meant Part 2 was delivered in late March 2020, exactly two years behind schedule.

Building on seminars on food systems dynamics and systems thinking, the course was highly interactive, with participants engaging in group exercises to develop skills as delivered in short introductory presentations.

Applied skills

Part 1 was very well received – as shown in the results of a post-course survey (Figure 1). Recognition of the importance of stakeholders and having the tools to integrate wider stakeholders into planning was valued by participants, as was the the style of training with its emphasis on participation and knowledge sharing. There was also clear demand for further understanding of food systems and systems approaches, a recognition of their importance of applicability, and the benefit of acquiring practical and useable methods.

When it came to the most useful elements, comments included “Understanding how to involve different stakeholders when proposing new strategies, e.g. stakeholder mapping”, “’Rich Pictures’ helped me to improve my understanding of complex problems”, and “Soft skills, such as communication, group dynamics, etc”.

Lasting impact

Part 2 training included SWOT analyses of current interventions to address food system issues, backcasting practice, and introduced foresight and scenarios methodology. Participants drew on their different areas of expertise and engaged in collaborative problem solving. They were also encouraged to engage in reflective discussion throughout on food system challenges and the methodologies shared in the training.

Two years on from the initial session, a survey conducted during Part 2 (Figure 2) provided information for a pedagogic analysis of Part 1, showing the lasting benefit to participants: “I have incorporated some ideas into the courses that I teach, and have also borrowed some ideas to feed into a research grant application”, “The whole idea of food systems has helped me in my service delivery which involves dealing with a lot of chemicals which affects the farmers, the environment, and the final consumers of the food” and “Proper planning and evaluation of my business goals through use of the swot analysis and back casting methods”.

Future activity

Despite the two-year delay, it was particularly pleasing that all but four of the Part 1 cohort returned for Part 2, supporting their Part 1 survey comments.

Deemed a success, the overall project has provided a clear indication of the demand for food systems thinking and practice among a varied group of academics and professionals. Further food systems training is planned in collaboration with RUFORUM and the Foresight4Food programme.

Dr John Ingram is the leader of the Food Systems Transformation Group at the Environmental Change Institute, University of Oxford.

Figure 1: Likert Scores from Survey Results January 2020

Figure 2: Pedagogic Survey Results March 2022

On scale of 1-5, 5 being greatly, how much do you think systems thinking has changed the way you think about food systems?