By Herman Brouwer, WUR lead for FoSTr and Wangeci Gitata-Kiriga, FoSTr Country Facilitator Kenya

How can foresight transform the lives of pastoralists, fishers, and farmers in Marsabit County, Kenya? Marsabit County faces formidable challenges, with the escalating impacts of climate change threatening its food systems and livelihoods. Despite decades of significant support from development partners and government initiatives, the tangible results remain limited. This begs the critical question, inspired by David Peter Stroh: Why, despite our collective best efforts, have we struggled to foster lasting, positive change in Marsabit’s food systems?

Foresight could hold the key. By enabling stakeholders to anticipate future challenges, identify sustainable solutions, and adapt to evolving realities, foresight offers a transformative approach to addressing the county’s persistent issues. It’s time to rethink strategies and align efforts to create meaningful, long-term change for Marsabit’s pastoralists, fisherfolk, and farmers.

We brought stakeholders together in December 2024 to explore the above question, and to make a start to imagine different futures for the food system in Marsabit. Naturally, this involved a highly interactive discussion on the current food system and how we got to this situation – using a data walk with up-to-date data and analysis, as well as system maps. This provided the basis to jointly understand the dynamics of how food systems change (or resist change) and imagine how the food system could change even further in the next 10-15 years. The stories that participants came up with, based on their lived experiences in four distinct sub-counties of Marsabit, evolved into four scenarios. We used one of these scenarios (the ‘ideal one’ called Ajako, meaning ‘paradise’ in the Borana language) to create a vision for the future. We then identified the initial pathways and building blocks required to work towards this Ajako scenario.

Photo credit: Crispaus Onkoba/SID, used with permission

That’s the summary of where we ended up. However, an essential detail was omitted earlier: How do you ensure the right individuals and institutions are in the room? Achieving this required a carefully planned stakeholder engagement process, which began several weeks before the workshop. The process involved numerous meetings with individual stakeholders across the county to understand who was doing what, who was most invested, what had been successful, and what hadn’t worked in the past. The ultimate goal was to mobilize the most relevant and diverse stakeholders for the 3-day workshop.

We started by engaging the county leadership, relevant government departments, and development partners. But stakeholder mobilization didn’t stop there. We actively sought out voices often overlooked in food systems discussions: faith-based organizations, community groups, and private sector representatives.

Following the workshop, we ensured the initial excitement and momentum were sustained by maintaining contact with key participants. This effort culminated in the formation of a County Development Group, coordinated by the county government. This group brings together all actors actively engaged in food security initiatives, creating a collaborative platform for sustained impact.

Photo credit: Crispaus Onkoba/SID, used with permission

We argue that the investment in stakeholder engagement has been the most valuable ingredient of the foresight process so far. It has allowed our Kenya foresight team to obtain the right endorsements and buy-in at the right levels. Without getting the engagement process right, all participatory foresight tools, and supportive analytics, are at risk of falling flat.

There is a case to be made to only report on foresight processes after they are concluded, rather than at the start. This blog is an exception, to make the point that how you start matters.

The FoSTr Kenya foresight team, consisting of Results for Africa Initiative (RAI); Society for International Development (SID); International Livestock Research Institute (ILRI); University of Nairobi; Food and Land Use Coalition (FOLU); Wageningen University & Research (WUR); and the University of Oxford, will continue to support the County Development Group in Marsabit to coordinate actions of state and non-state actors towards achieving Ajako by 2040. A similar process is taking place in Nakuru County. Both have active linkages to Kenya’s national food system science-policy interfaces.

By Jim Woodhill, Foresight4Food Initiative Lead

Last month (November 2023) I had the wonderful experience of engaging with over fifty young leaders from across Africa, joined by colleagues from Bangladesh, Nepal, and Jordan. We had all gathered in Naivasha, Kenya, to explore how skills in facilitating foresight can be used to help bring about food systems transformation.

The fascinating work these young leaders are involved in and their deep interest in understanding how to be more effective change-makers was truly inspiring. It was encouraging to see how valuable they found the foresight for the food systems change framework and the associated set of participatory tools for engaging stakeholders.

Participants all came with projects from their own countries where they are keen to use foresight and systems thinking to help facilitate change in food systems by bringing together different stakeholders. The participants were from diverse backgrounds representing policy, the private sector, NGOs, and academia.

A Guiding Framework: During the workshop we introduced participants to an overall guiding framework for facilitating foresight for food systems change. A range of participatory tools were used for systems analysis, development of future scenarios and exploring systemic interventions. To bring reality into the workshop, the Kenya horticulture sector was used as a case study for the foresight analysis. Participants spent a day visiting horticulture farms, packing and processing facilities and the local market. They explored with local stakeholders how they saw the future for the horticulture sector and the issues that “keep them awake at night”.

Visualising the system: The workshop was highly interactive with participants practicing in the facilitation of a range of participatory tools which can be used to bring stakeholders into dialogue around systems change. One of my favourite participatory tools “rich picturing”, which enables a diverse group of stakeholders to develop a shared understanding of a system by drawing it, was found by participants to be especially powerful.

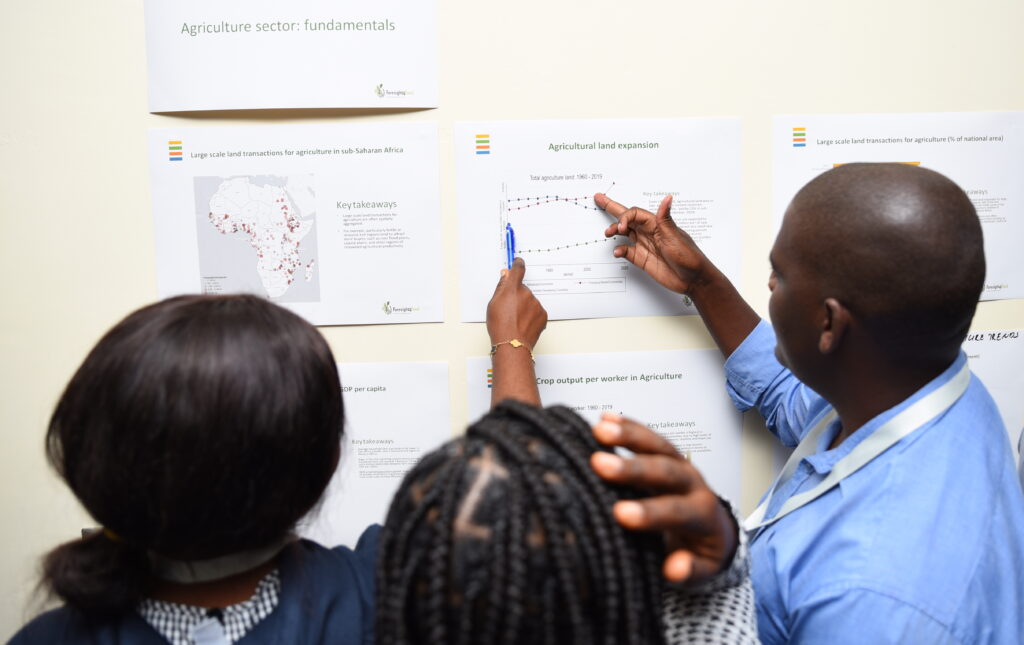

Data-driven dialogue: To go deeper into the systems analysis it is valuable for stakeholders to explore the available data on key drivers and trends. Over 100 graphs visualizing key data points related to the Kenya horticulture sector and food systems at national, continental, and global scales were collated and posted around the walls. The participants then explored this data in groups of three and discussed its implications and how it perhaps challenged their existing assumptions.

Exploring the future using scenarios: Central to the foresight approach is developing a range of different plausible future scenarios (generally with a 10 to 30-year horizon) for how the system might evolve given critical uncertainties. Workshop participants did this for the horticulture sector, looking at factors such as how diets might change in the future, regional and global trading relations, severity of climate change, and the enabling policy environment for small-scale producers and the small- and medium-scale enterprises (SME) sector. The scenarios help to identify future risks and opportunities for different stakeholder groups and society at large. They also help to unlock creative thinking about how to “nudge” systems towards more desirable futures and away from less desirable ones.

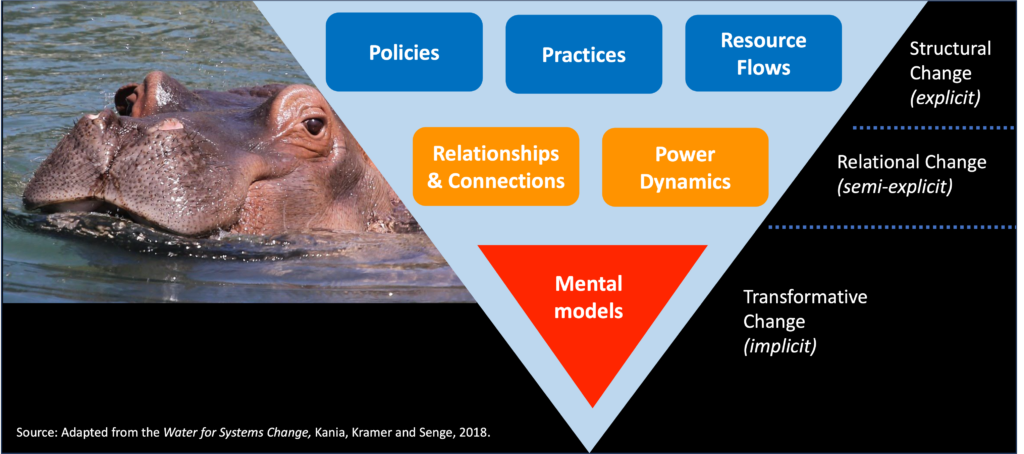

The deeper issues of systems change: It is easy to talk about systems change. In reality trying to change systems bumps into all the difficult issues of vested interests, power relations, ideologies, and deeply held cultural beliefs. On top of this human and natural systems are complex and adaptive and behave in self-organising, dynamic, and often unpredictable ways. It doesn’t mean you can’t intervene to try and bring positive change. But it does mean that top-down, linear, and mechanistic models of change generally don’t work. The workshop engaged participants in deep and challenging discussions about what it means to be a leader of systems change. This included the need to be adaptive, how to create alliances for disrupting existing power relations, the importance of building relations between diverse stakeholders, and the importance of patience. Systems change often requires taking time to build the foundations for change without being able to know when circumstances might suddenly unlock opportunities for big steps forward.

Identifying directions for change and intervention options: Developing directions and pathways for systems change is the most difficult and challenging part of the foresight for systems change process. It is highly context-specific and requires a deep insight into the political economy of the situation. Cause and effect mapping, theory of change thinking, and causal loop analysis can all help in identifying opportunities for intervening which could help to drive systems change in desired directions. Bringing change will often require an integrated approach to technological, institutional and political innovation. During the workshop causal loop diagrams were used to explore possible entry points for shifting horticulture systems in ways that could improve health, livelihoods and the environment.

New friends, new networks and big ambitions: After an intense week of learning and sharing participants left inspired to apply the foresight approach back in their own work environment. New friends were made and there were clear calls to find mechanisms to support ongoing networking and peer support.

Many thanks to the facilitation and support team who made a fantastic week possible, Gosia McFarlane, Marie Parramon-Gurney, Kristin Muthui, Bram Peters, Joost Guijt, Riti Herman Mostert, and Abdulrazak Ibrahim. The event was made possible by support from the Mastercard Foundation.

More information about the Foresight4Food Framework of Foresight for Food Systems Change can be found on our website, and an updated approach paper will be published in January 2024.

By Just Dengerink

Foresight training for Africa Foresight Academy by Foresight4Food researchers and Wageningen University & Research (WUR)

The Foresight4Food initiative aims to connect and inspire networks of foresight professionals around the world. In early July 2022, members of the Africa Foresight Academy participated in a foresight training at Oxford, provided by Foresight4Food researchers from the University of Oxford’s Environmental Change Institute (ECI) in collaboration with Wageningen University & Research (WUR). The training was attended by five African researchers in person, while five others joined in online.

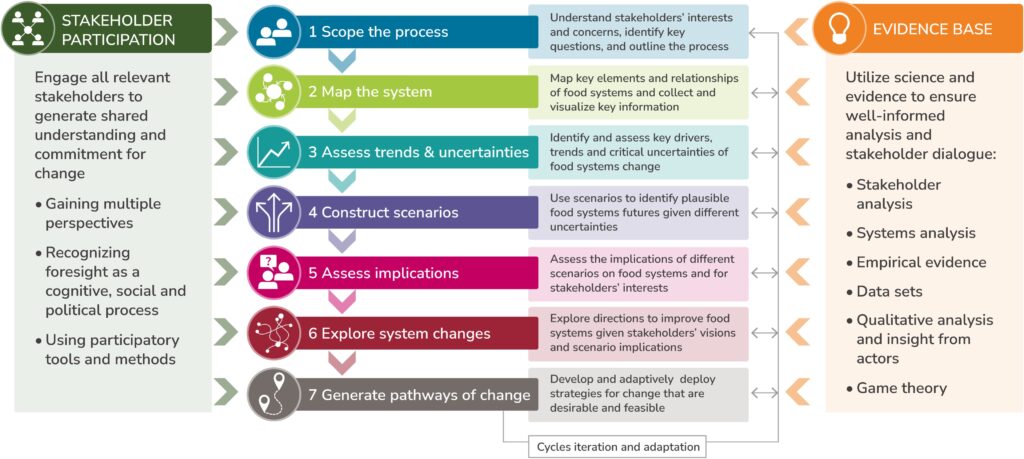

The Foresight4Food ‘seven steps’ approach to scenario and foresight analysis (see illustration below) was used to develop four scenarios for a more climate-resilient Ghana in 2040. Here’s a look at how these scenarios were developed using the Foresight4Food approach in the training session.

Scoping the process and mapping the food system

The scenario exercise started with scoping and delineating the focus of the scenario process Collectively, it was decided to focus the scenarios on the future of the Ghana food system in 2040, and the resilience of this system to external shocks related to climate change.

Participants were invited to draw a ‘rich picture’ of the Ghana food system to map out its most important features. These included small-scale yam and cocoa production in the south, maize and sorghum production in the north, fisheries along the coast and around Lake Volta along with the role of urban informal food markets, the lack of a large food processing sector, Covid-19’s impact on supply chains, growing security threats in the region, and the effect of the war in Ukraine on fuel prices and availability of fertilizers.

From assessing trends and uncertainties to constructing scenarios

Building upon the key features of the Ghana food system from the ‘rich picture’ exercise, participants were then invited to identify the most important trends and uncertainties affecting the Ghana food system.

Highlighted key trends included fast population growth and urbanization, increasing use of technology, growing dependence on food imports and remittances, decreasing occurrence of crop diseases, growing youth unemployment, and the increase in fast food consumption.

Together, the participants also identified some important uncertainties regarding the future of the Ghana food system: the degree of extreme weather events, the implementation efficiency of climate resilience policies, and the vulnerability of households to climate change. Other uncertainties identified included future access to fertilizers, fluctuations in fuel prices, changes in trade regimes, levels of agricultural productivity, the expected value of the Ghanaian currency, the potential influence of future Covid outbreaks and the impact of developments in the general security of the region.

The participants then decided on two key uncertainties that would be critical in determining the future climate resilience of the Ghanaian food system. Based on these two key uncertainties, a matrix was created with each of the axes representing one uncertainty. Within this matrix, four scenarios were constructed, based on their position on both axes and with input from the other uncertainties that were identified.

Assessing implications, exploring system changes and designing pathways

With the four scenarios in place, participants were invited to give more colour to these four plausible futures by exploring the implications of each scenario for different stakeholder groups. One group explored the implications for rural farmers, while the other focused on urban consumers.

With the implications of each scenario explored in more detail, participants were asked to zoom out and think about the possible system changes that – in each scenario – could contribute to a more climate-resilient future of the Ghanaian food system. Suggestions included the stimulation of climate-smart agriculture practices, diversification of production and dietary patterns, strengthening regional trade, supporting home gardens and peri-urban agriculture and digitalization of supply chain management.

This three-day exercise with African foresight experts showed how the Foresight4Food approach can help structure a participatory foresight process that leads to engaging scenarios and actionable policy recommendations to shape the future of our food systems.

An update on a two-part IFSTAL training course held at Makerere University

Bring together 26 individuals drawn from university students, academics and professionals working across the food sector in Uganda and what do you have? The kernel of a powerful network to help tackle malnutrition in country in all its varied forms.

Equipping participants with the skills to become food systems thinkers was the aim of a two-part training course delivered by Interdisciplinary Food System Teaching and Learning’ programme (IFSTAL) in collaboration with Makerere University, Kampala.

Malnutrition is the new normal

Despite the emergence of food systems approaches to address food insecurity in the content of other SDGs, malnutrition in Africa is becoming the ‘new normal’. This is down to a lack of skills across the policy and practice workforce to tackle food system challenges in the necessary integrated manner.

Fixing systemic problems across the food sector while enhancing livelihoods needs interdisciplinary systems thinkers. The lack of sufficient food systems training – and hence skills in the workforce – is a major impediment. This is partly due to university curricula being ill-equipped to provide the necessary interdisciplinary food systems training for students who will move on into the food sector, and partly due to weak networking across the sector itself.

Creating skills for change

Generously supported with a grant from the Open Society Foundations, the course was planned in two parts. Part 1 held in January 2020, covered basic food systems approaches. Giving participants time to reflect on the first part in their work contexts, Part 2 was designed to follow three months later, covering system change and foresight. Covid-19 intervened, which meant Part 2 was delivered in late March 2020, exactly two years behind schedule.

Building on seminars on food systems dynamics and systems thinking, the course was highly interactive, with participants engaging in group exercises to develop skills as delivered in short introductory presentations.

Applied skills

Part 1 was very well received – as shown in the results of a post-course survey (Figure 1). Recognition of the importance of stakeholders and having the tools to integrate wider stakeholders into planning was valued by participants, as was the the style of training with its emphasis on participation and knowledge sharing. There was also clear demand for further understanding of food systems and systems approaches, a recognition of their importance of applicability, and the benefit of acquiring practical and useable methods.

When it came to the most useful elements, comments included “Understanding how to involve different stakeholders when proposing new strategies, e.g. stakeholder mapping”, “’Rich Pictures’ helped me to improve my understanding of complex problems”, and “Soft skills, such as communication, group dynamics, etc”.

Lasting impact

Part 2 training included SWOT analyses of current interventions to address food system issues, backcasting practice, and introduced foresight and scenarios methodology. Participants drew on their different areas of expertise and engaged in collaborative problem solving. They were also encouraged to engage in reflective discussion throughout on food system challenges and the methodologies shared in the training.

Two years on from the initial session, a survey conducted during Part 2 (Figure 2) provided information for a pedagogic analysis of Part 1, showing the lasting benefit to participants: “I have incorporated some ideas into the courses that I teach, and have also borrowed some ideas to feed into a research grant application”, “The whole idea of food systems has helped me in my service delivery which involves dealing with a lot of chemicals which affects the farmers, the environment, and the final consumers of the food” and “Proper planning and evaluation of my business goals through use of the swot analysis and back casting methods”.

Future activity

Despite the two-year delay, it was particularly pleasing that all but four of the Part 1 cohort returned for Part 2, supporting their Part 1 survey comments.

Deemed a success, the overall project has provided a clear indication of the demand for food systems thinking and practice among a varied group of academics and professionals. Further food systems training is planned in collaboration with RUFORUM and the Foresight4Food programme.

Dr John Ingram is the leader of the Food Systems Transformation Group at the Environmental Change Institute, University of Oxford.

Figure 1: Likert Scores from Survey Results January 2020

Figure 2: Pedagogic Survey Results March 2022

On scale of 1-5, 5 being greatly, how much do you think systems thinking has changed the way you think about food systems?