There are varying degrees of involvement by the national governments and international governance structure in food production, distribution, and regulation of food safety standards, markets and food environments. The extent of governmental involvement in food-related policies, regulations, and support programs shapes market dynamics, food safety standards, and access to resources, influencing the overall stability and equity of the food system.

This section presents selected data on key trends in policy and geopolitics:

- Financial Support (Subsidies and Incentives)

- Inequalities in the Support System

- Loss of Indigenous Food and Knowledge Systems

1. Financial Support (Subsidies and Incentives)

Trends

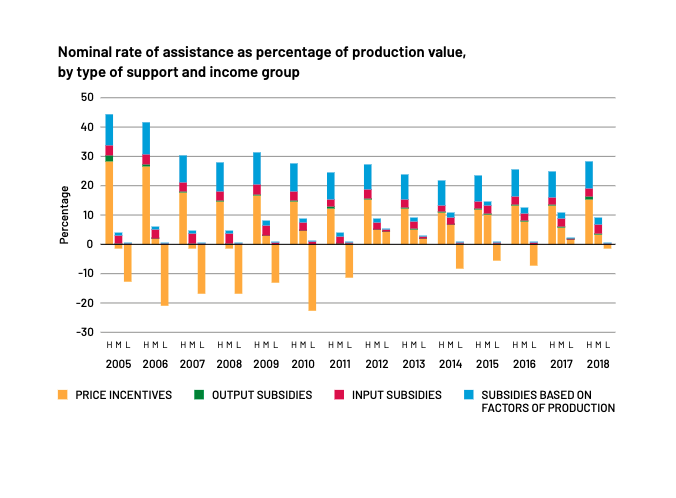

Support for agricultural producers varies significantly across income groups. In high-income countries (HICs), support has been declining, driven by efforts to repurpose policies toward environmentally sustainable practices and the reduced economic role of agriculture. In 2018, most support came through price incentives and subsidies based on production factors. In middle-income countries (MICs), agricultural support has increased since 2005, peaking at 14% of production value in 2015, though support policies vary across countries. Between 2016 and 2018, price incentives, input subsidies, and production-based subsidies were the primary forms of assistance. In low-income countries (LICs), particularly in sub-Saharan Africa (SSA), agricultural producers are often penalized due to government price controls aimed at ensuring affordable food for the population. This results in a resource transfer from producers to consumers. Some LICs provide limited input subsidies, though these remain insufficient to compensate for suppressed prices (FAO, UNDP, UNEP 2021).

Implications

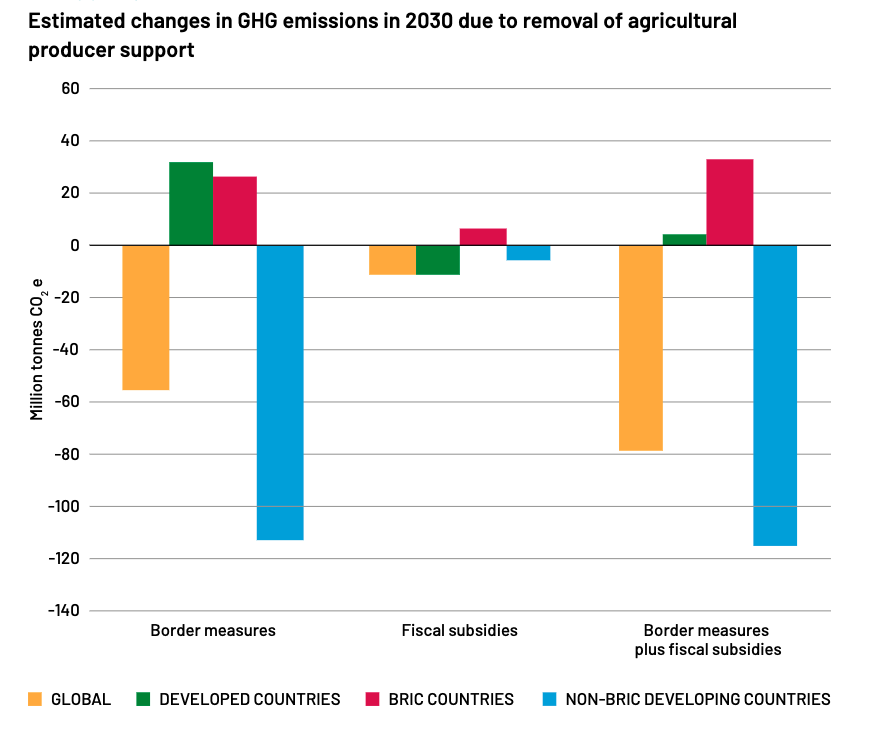

Subsidies coupled with government procurement of agricultural products, can inadvertently exacerbate pressure on natural resources for example by promoting use of synthetic fertiliser, ground water pumping, expansion of land etc. In fisheries, subsidies have fuelled overcapacity, leading to overfishing. While intended to boost production and food security, these subsidies often drive agricultural expansion, causing environmental damage and undermining the ecosystem services essential for sustainable food systems (FAO, 2017). A modelling exercise conducted by FAO reveals that simply removing agricultural support may have important adverse trade-offs.

For example, in an extreme scenario whereby all agricultural support was removed by 2030 without being repurposed, GHG emissions are projected to fall by 78.4 million tonnes of CO2e, but crop production, livestock farming production and farm employment are also projected to decrease by 1.3, 0.2 and 1.3 per cent, respectively (FAO, UNDP, UNEP 2021). Subsidies need to be adjusted and balanced to drive sustainable food system transformation. In the past decade, OECD governments were on average allocating roughly 26% of their subsidy support to cereal grains, and 14% to fruits and vegetables. Interestingly, the share of sectoral support for fruits and vegetables was much higher in non-OECD countries at 37%. Reallocation of subsidies to nutrient-rich fruits and vegetables will have a huge positive health outcome. However, it needs to be balanced with profitable commodities for economic growth (Scenarios for rebalancing subsidies (Global Panel, 2020).

2. Inequalities in the Support System

High-value Crop Growers vs. Indigenous Growers

As part of the climate change adaptation strategies, there is a global and national focus in international research, subsidies, and support for a few crop species (mainly high-value crops) has contributed to an overall decline in agrobiodiversity. There is a lack of research and innovation to support smallholders growing minor crops (FAO 2019).

For example- In the Andean Altiplano of Bolivia, indigenous farmers have traditionally managed a diverse set of native crops which are drought and frost-tolerant, using cultural practices of seed selection and exchange, but have faced an increase in pests and diseases and a decline of traditional crops due to climate change related stresses, out-migration and intensification drivers (IPCC, 2022). There is a possibility that a lack of adaptive capacity and policy support will drive farmers to move away from diverse crops, further reducing the resilience of food systems by increasing the risk of crop loss from pests, disease and drought and the potential loss of Indigenous or local knowledge (IPCC, 2022).

3. Loss of Indigenous Food and Knowledge Systems

Nineteen per cent of the people who face extreme poverty worldwide are indigenous (FAO, 2022). This economic poverty is in sharp contrast to the cultural and ecological richness of indigenous societies. Indigenous cropping practices contribute to agricultural biodiversity, resilience, and cultural heritage preservation. The conservation of these cultures and recognition of indigenous knowledge are important for sustainable food production, resilience to environmental stressors, and food system governance that leads to equity and fairness.

FAO (FAO, 2022) and HLPE (HLPE, 2020) reports highlight that despite the indigenous food systems being the most resilient systems, indigenous people’s knowledge is at risk of disappearing in the near future due to a lack of dedicated policies and the multitude of issues associated with poverty, food industrialisation, urban growth, political violence, climate change impacts and forced displacement of these communities for conserving and protecting areas. There is no data that can illustrate this trend. Enhancing the potential of indigenous people’s food and knowledge systems can support SDG 1, SDG 2, SDG 5, SDG 10, SDG 12 and SDG 15.

4. Decreasing Multilateralism

Multilateralism is under severe strain as the global order undergoes a profound transformation. Great power competition and the rise of populist nationalism have eroded the foundations of international cooperation. The paralysis of key institutions like the World Trade Organisation (WTO) and United Nations Security Council (UNSC) is a stark symptom of this decline.

A shifting geopolitical landscape, characterised by the West’s relative decline and the East’s ascent, coupled with the growing influence of non-state actors, has created a volatile environment marked by instability and unpredictability. FAO (FAO 2022) reports this trend leading to major uncertainties for conflicts and crises. In 2016, more countries experienced violent conflict than at any time in nearly 30 years. In 2019, there were 54 active armed conflicts in the world, up from 52 in 2018 and matching the post–Cold War peak of 2016.