Globally, the food system is a major sector of employment, supporting the livelihoods of hundreds of millions of people across all stages of the value chain in both rural and urban areas. However, food system workers are among the world’s poorest and most marginalized, often facing exploitation, labour rights violations, inequitable wages, and other forms of harassment, especially by indigenous people, women and children. Transforming food systems is essential to achieving just and equitable livelihoods, and fostering social resilience for all who work within the system. There are no direct indicators of livelihood enhancement, equitable income and social wellness of the people involved in the global food system. Moreover, compared with other themes, the available data are more limited due to a lack of disaggregation to distinguish food system livelihoods from others. However we can use four key indicator domains as a proxy of their well-being: income and poverty, employment, social protection, and rights.

The data presented here is taken from FAO Statistics Working Paper Series- Estimating Global And Country-Level Employment In Agrifood Systems. Food Systems Dashboard, FAO’s Rural Livelihoods Information System, and World Bank data- ASPIRE are some of the leading sources of quantitative indicators of employment and social well-being in the agri-food sector.

Income and inequality

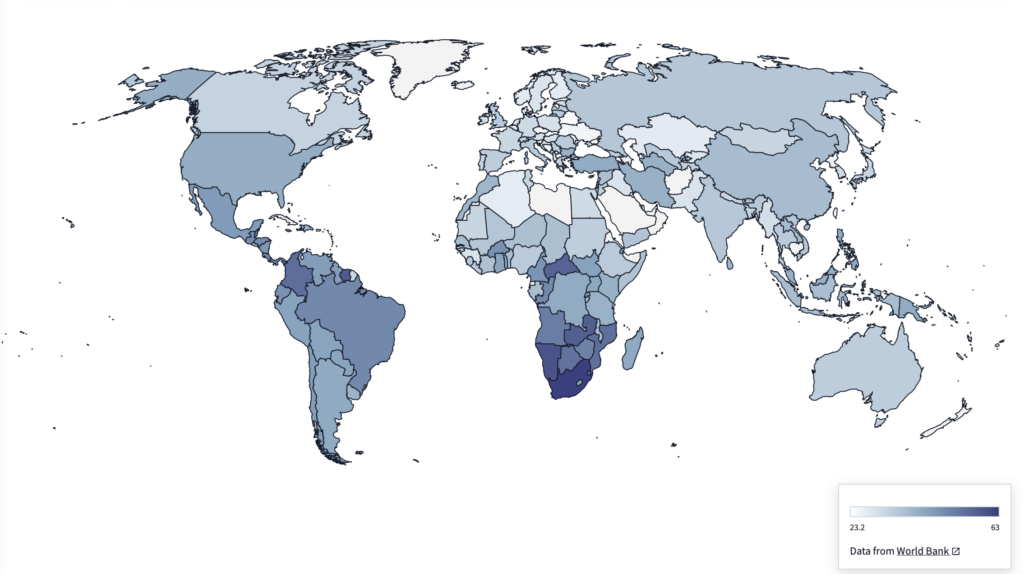

Globally, labourers in the food sector are amongst the poorest. Moreover, there is a big income gap between the poorest 10% and the richest 10% (ILO, 2019). The long-term trajectory of poverty eradication and income gaps changed since the COVID-19 pandemic as many people lost jobs in low-income countries. According to the Gini Index, high-income inequalities are faced in Southern Africa and South American countries. However, in the sustainable, increased productivity and equitable growth scenarios (SSP1 and SSP5), poverty and inequalities are projected to reduce (FAO, 2022).

Source: World Bank Data – mapped by Food system dashboard

Source: FAO, 2022

GDP

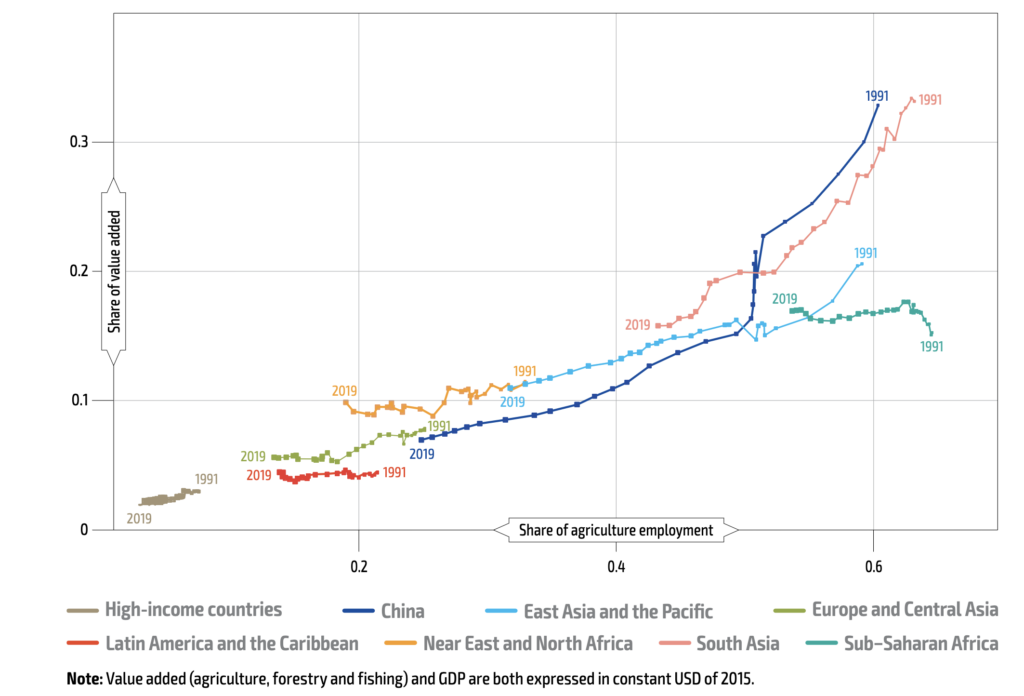

Declining GDP from agriculture (graph below) and fewer people working in agriculture are hallmarks of the structural transformation process that is integral to poverty reduction and rural transformation. Estimating the contribution of the global food system to the national GDP and economic growth is challenging due to its complex nature. A model has been developed by Planet Tracker that provides some estimations of the economic value of the Global Food System using a database of 4000,000 companies related to the food system. It is estimated that the global food system generate revenue which is equivalent to between 16 and 20% of Global GDP. It’s noteworthy that up to 70% of revenues come from 0.06% of all companies.

Source: FAO, 2022

Employment in Agri-Food Sector (AFS)

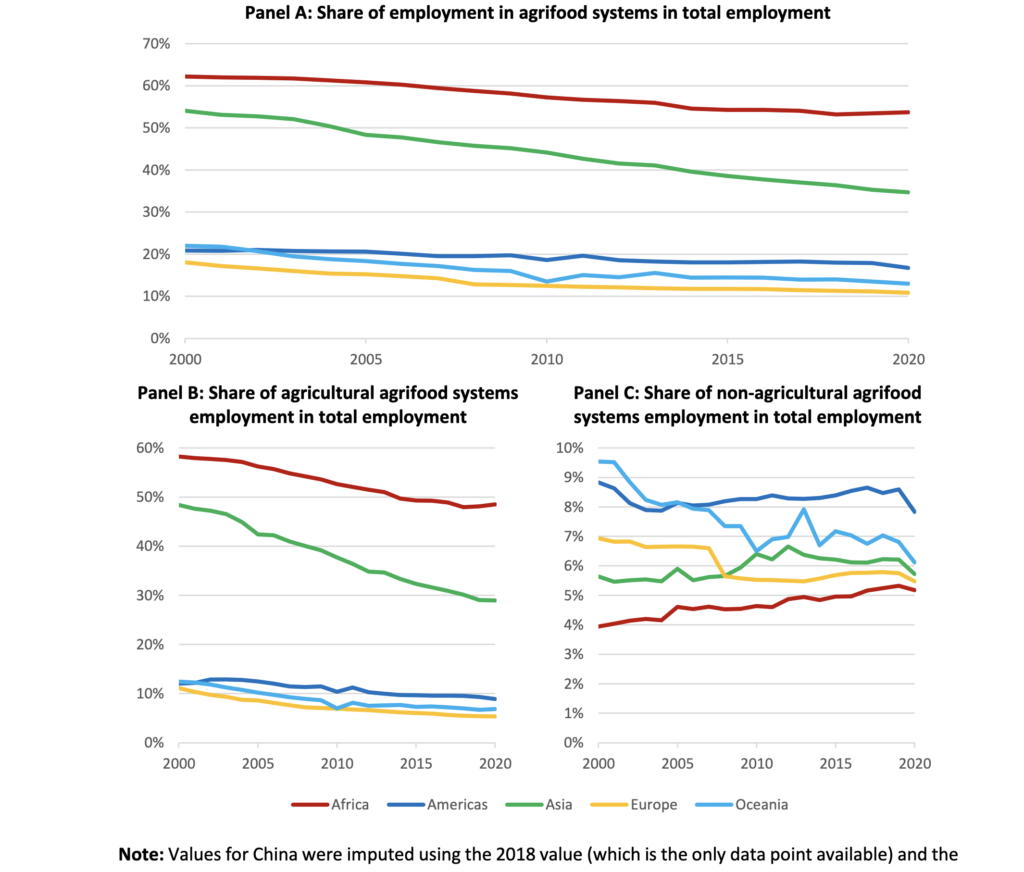

In 2019, food systems provided employment for 1.23 billion people and (including household members) supported over 3.83 billion livelihoods, in all stages of the value chain across rural and urban areas. With the growth in urbanisation, employment in agriculture is falling with labour moving to other sectors, often food-related (food manufacturing, logistics, distribution and retail). Job migration is also an important driver in the food system influencing the livelihood and social well-being outcomes.

As shown in the figure below (panel A), across regions over time, the share of employment in AFS has been declining, attributed to the decline in the share of people employed in agriculture (panel B). The share of those employed in non-agricultural AFS remains relatively low as a share of total employment (panel C) but shows an increasing trend notably in Africa.

Source: Estimating employment in agrifood systems FAO, 2023

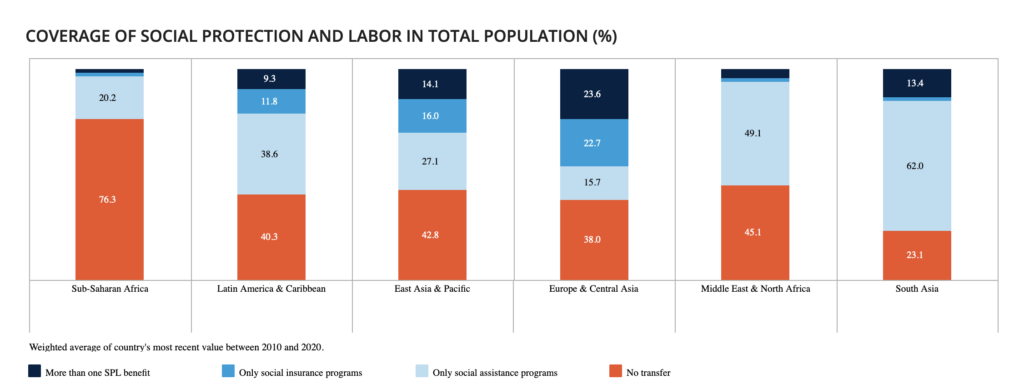

Social Protection Coverage

Social protection as a result of holistic agri-food policies and equitable growth in the sector is an indicator as well as a driver of food security, equity and social wellness. Programs dedicated to social protection have been impactful in combating poverty for small-scale food producers and informal workers who face chronic food insecurity and vulnerability to shocks. As shown in the figure below, in Sub-Saharan Africa, the coverage of social protection is the lowest compared to the rest of the world, indicating the need for stronger policies for building the resilience of the poorest and the marginalised food system labours in the region.

Source: WB- The Atlas of Social Protection Indicators of Resilience and Equity (ASPIRE)