By Jim Woodhill, Lead Foresight4Food Initiative

Last week, I had the wonderful opportunity to support a regional training workshop on foresight for systems change in Nepal, in collaboration with the International Centre for Integrated Mountain Development (ICIMOD).

The workshop brought together a group of 35 development practitioners from across the Hindu Kush Himalaya region, including participants from Nepal, Bangladesh, Bhutan, India, and Pakistan. The focus was on how to use foresight to help tackle the big regional issues of climate adaptation, creating diversified and resilient livelihoods in mountain areas, migration, and disaster preparedness.

ICIMOD invited Foresight4Food to collaborate in facilitating the training, using Foresight4Food’s Framework of foresight for systems change following the organization’s participation in a similar leaders capacity development workshop held in Africa in 2023 (see report and video here) and Foresight4Food’s 4th Global Meeting in Bangladesh.

The Nepal event was a good chance to build on Foresight4Food’s capacity development experience in Kenya, Jordan, Bangladesh, and Uganda. These are focus countries for the Foresight for Food Systems Transformation (FoSTr) programme, supported by the International Fund for Agricultural Development with funding from the Dutch Government.

While food issues were only part of the focus of the workshop, the issues raised during the week yet again highlighted that the way food is consumed and produced is central to all development issues. Migration, climate adaptation, equitable livelihoods and managing disasters are all interconnected with agrifood systems.

What was covered in the training workshop?

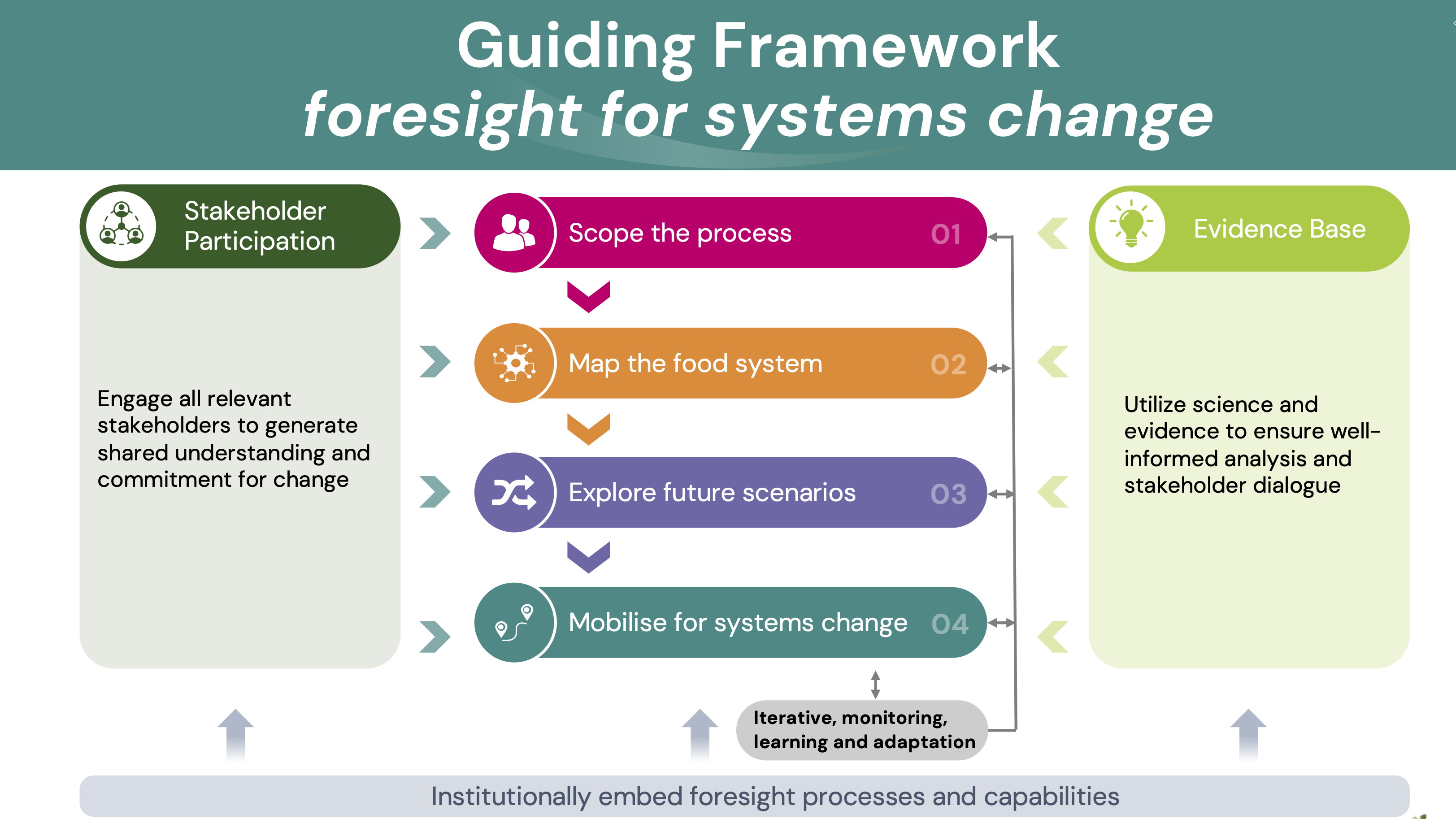

During the week, the participants worked through the four main phases of the Foresight4Food Framework:

- Scoping the process

- Mapping the system

- Exploring future scenarios

- Mobilising for systems change

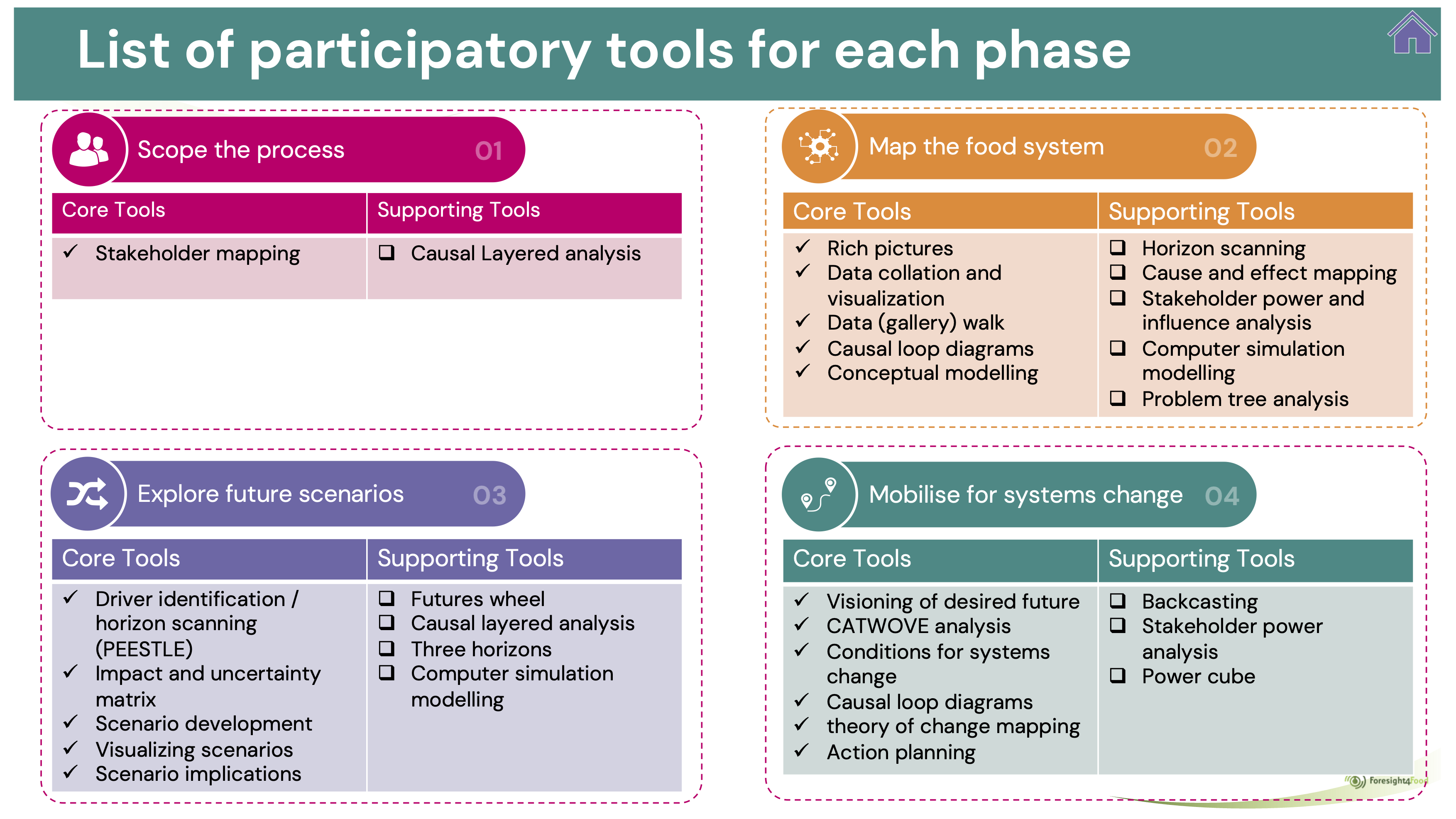

For each phase, participants were introduced to background concepts and theory, and relevant participatory foresight and systems thinking tools. Rich pictures, drawn by participants to illustrate the whole system, is always a favourite. Other tools we worked with included horizon scanning of future trends and uncertainties (guided by the PEESTLE acronym), data exploration, causal loop diagrams, scenario development, visioning, back casting and conceptual modelling of systems.

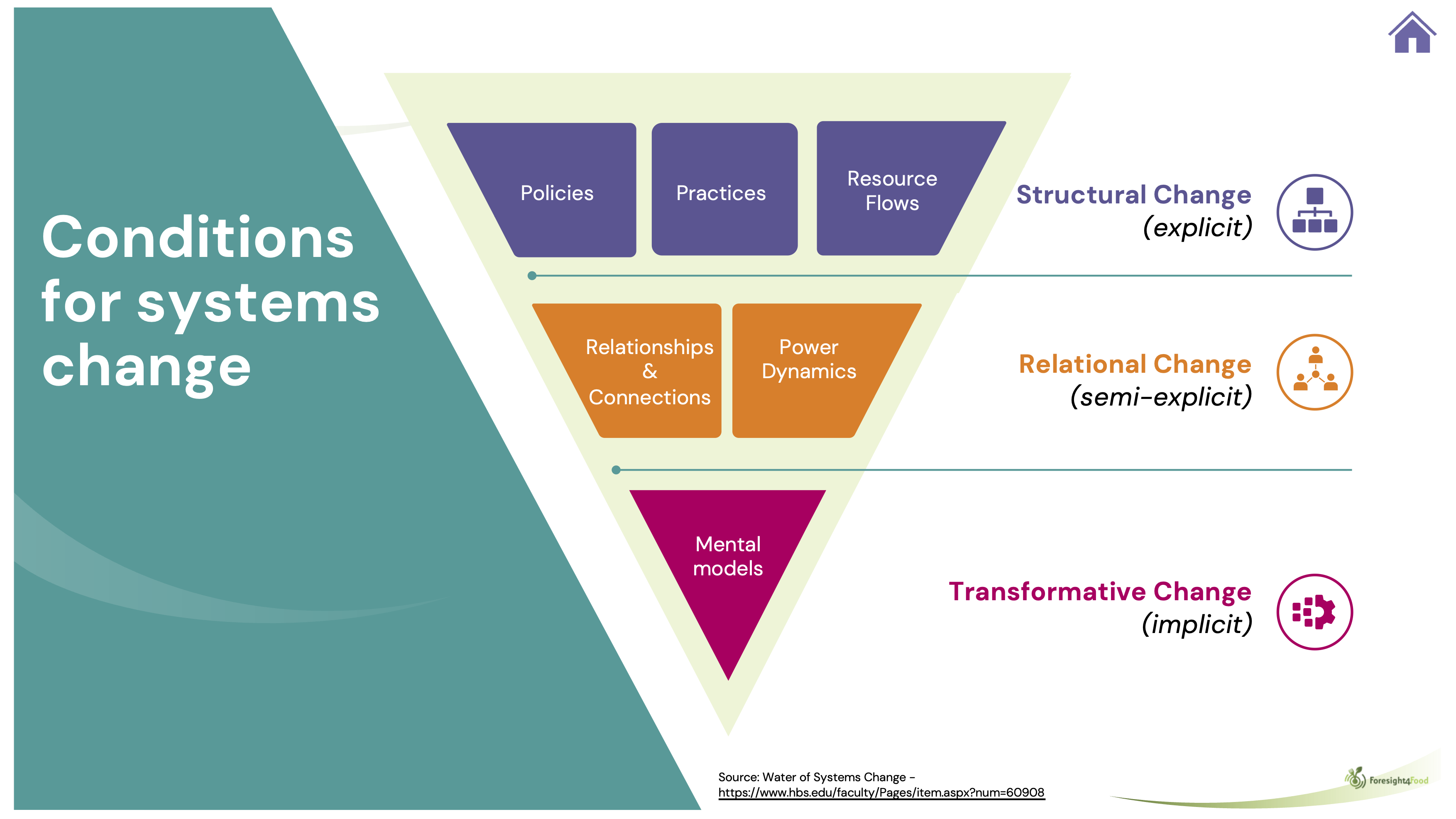

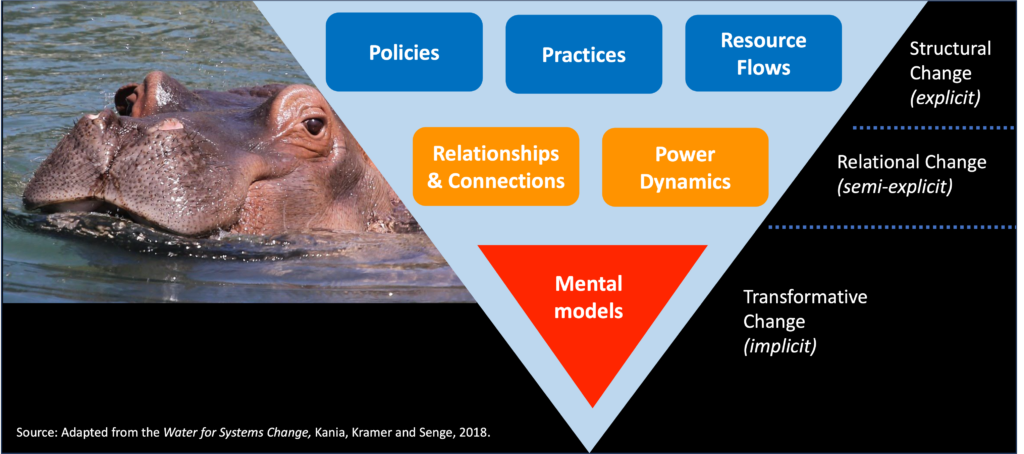

We discussed how change happens in complex adaptive (human) systems. The systems change “triangle” helped thinking about the role that mindsets and different forms of social and political power play in enabling or constraining change. The importance of bringing a gender equity and social inclusion (GESI) perspective to foresight was highlighted.

Participants applied their learning directly to the issues of climate adaptation, pastoralism, migration, and disaster preparedness.

The need for foresight

The global polycrisis is having a big impact on the Himalayas. The confluence of climate change, conflict, disease risk, inequality, biodiversity loss and geopolitical instability are bringing high levels of uncertainty and turbulence for citizens, businesses and governments across the region. For example, the melting of glaciers and the impact of extreme rainfall has profound implications for life in the mountains as well as for the billions of people who depend on the river systems that flow out of the Himalayas.

The Himalayas sit in the middle of a region with significant political tensions and shifting powers, which has major implications for the collaborative governance needed to effectively respond.

Foresight for systems change can help communities, organisations and governments better anticipate future risks and reimagine the future, so as to be more adaptive and resilient.

Thinking ‘out of the box’ – Foresight or “shortsight”?

Challenging discussions emerged during the week about how to ensure that foresight processes don’t just end up with the same old stuff – “old wine in new bottles”. To avoid this, we explored the need for “out of the box” thinking. This means looking for weak signals that might indicate a coming disruption, challenging assumptions about the future, bringing different perspectives to the table, using creative techniques to imagine radically different futures, and using the insights of “futurists”. A comprehensive horizon scanning process that explores mega-trends, trends, weak signals, critical uncertainties and wildcards helps to ensure foresight rather than “shortsight”.

Beyond tokenistic stakeholder participation

Across the Himalayas, it is local communities, local government and local businesses who must cope with the direct impact of floods, extreme heat, price fluctuations or disease outbreaks. Time and again participants returned to the importance of engaging local stakeholders to understand the challenges, and to generate pathways for greater resilience.

The discussion led to a shared understanding that this kind of participation from stakeholders requires genuine and open dialogue, made possible by using participatory workshop tools and techniques. However, all too often stakeholder engagement processes, when they do happen, fall back to formalised meeting structures, with speeches and presentations by “important” people, with little or no use of the sort of participatory analysis and dialogues tools participants engaged in during the training week. Advocating for effective, participatory and transformative stakeholder engagement processes is an obvious role for ICIMOD.

Institutional barriers to foresight and systemic practice

At the end of the week participants explored how to use foresight and systems thinking and practice in their own working context. Then some of the realities hit home.

Funders and donors often still force very linear, short-term and inflexible modes of programme design and management. Policymakers struggle to work effectively in a cross-ministerial way. People who see themselves as “senior” resist rolling up their sleeves and actively engaging in participatory processes with other stakeholders. Response strategies often stick to the safe space of technical analysis and technical solutions ignoring how mindsets and power structures block transformational change.

These are challenges that organisations like ICIMOD and initiatives like Foresight4Food need to help tackle if foresight is to have a real impact on policy and local action.

Cultivating a cadre of foresight and systems change practitioners

Participants recognised there is a limited number of practitioners/professionals across the region who have the knowledge, skills and experience to effectively design and facilitate foresight and systems change processes. A big effort is needed to create a cadre of practitioners who do have these capabilities.

To tackle this gap, governments can develop foresight units, universities could make futures literacy and systems thinking part of their curriculum, and development organisations need to in invest more in such human capabilities.

Way forward

On the last day of the workshop, the “collective intelligence” of participants was used to start framing a new horizon scan for the region that could follow up on the highly influential 2019 HIMAP report on the region.

Participants left with many practical ideas of how they could apply the foresight thinking and tools directly to their work.

For ICIMOD and Foresight4Food hopefully, this was just the start of collaborating to strengthen regional capacities for foresight.

The energy and commitment of participants were astounding, especially given long days of challenging discussions.

All in all, it was a super inspiring week – giving hope that with committed people like those in the workshop, supported by organisations like ICIMOD, we can together create a more resilient and equitable future.

By Jim Woodhill, Lead Foresight4Food Initiative

Why do we need to transform our food system and how can foresight help?

The way food is consumed and produced is central to the polycrisis afflicting today’s world – said Ravi Khetarpal (APAARI), Amina Maharjan (ICIMOD), and Patrick Caron (University of Montpellier) in their keynote presentations at the 4th Global Foresight4Food Workshop.

The Foresight4Food Initiative held its fourth global gathering in the beautiful setting of BCDM Savar, Dhaka from June 3 to 7, 2024. Over 120 foresight practitioners from across 22 countries came together to share ideas and discuss the latest thinking on applying foresight to the challenges of transforming food systems. The event was hosted by the Government of Bangladesh and the Global Alliance for Improved Nutrition (GAIN) Bangladesh, with support from the Food and Agriculture Organization (FAO) and the World Food Programme in Bangladesh.

In a highly interactive week, participants engaged in a masterclass on foresight approaches, shared their experiences and lessons, heard from thought-leaders on food systems and foresight, and identified ways of strengthening foresight practice in their own countries and regions.

What does the future hold for our food systems?

Feeding the world contributes over 30% of greenhouse gases, and without change increasing population and wealth will drive this even higher. Meanwhile, diets are changing, often towards more unhealthy options. It is estimated that, by 2035, diet-related poor health could cost the global economy about 3% of GDP annually: this is the same negative impact that COVID-19 had on the economy. Environmentally, land use associated with food production is the main reason for the world’s massive loss of biodiversity and collapsing ecosystems.

And all of this is set against a background of increasing geopolitical tensions, and uncertainties for trade and access to resources.

As discussed during the different workshop sessions, foresight helps to understand the longer-term consequences of these trends, and the risks of “business as usual”. Even more importantly, participatory foresight and scenario development engages stakeholders in imagining how the future for our food systems could be different, in order to achieve sustainability, equity and resilience.

Highlights of the week included:

- Sixteen case studies on the use of foresight across Africa, Asia and the Middle East shared by participants – offering a wealth of insights, lessons and inspiration.

- Senior-level engagement from the Government of Bangladesh with insight into how foresight is seen as a key tool for helping to achieve their goals for food systems transformation.

- A deeper look at simulation modelling for foresight, and how a combination of qualitative and quantitative approaches can bring a range of important insights.

- Reflections on ensuring foresight processes are inclusive and consider gender dynamics.

- Six thematic sessions on cutting edge foresight issues which helped in mapping out a forward agenda for Foresight4Food.

- Strategic sessions on knowledge platforms and financing of food systems.

- Field trips where participants used insights from food system issues in Bangladesh to stimulate discussion on the future of the food system and sharing of cross-country lessons and experiences.

From my perspective, the key takeaways from the week were:

- The value of connecting foresight with a deeper understanding of the political economy of systems change, which is needed to help tackle the structural barriers to transforming food systems.

- Recognition of the critical importance of effective multi-stakeholder processes at national and local levels in driving food systems change, and the value of the foresight for systems change approach in supporting such processes.

- The necessity of increasing and reconfiguring investments in food systems and the need for this to be informed by the longer-term perspectives that foresight can bring.

- The value of integrating participatory foresight processes with quantitative modelling and use of data, while realising the constraints of limited food systems data at national and local levels.

- The importance of having foresight units and processes institutionally embedded in government, with a mandate and scope to challenge policy assumptions.

- A recognized need and growing demand for enhancing the capacities of policymakers, researchers and think tanks/consultants to design, facilitate and use foresight processes.

Participants left highly motivated to take forward the foresight work they are involved in and to help support the Foresight4Food network. The event ended with strong calls for the network to collaborate in helping to set up regional foresight support hubs across different continents.

By Jim Woodhill, Foresight4Food Initiative Lead

Last month (November 2023) I had the wonderful experience of engaging with over fifty young leaders from across Africa, joined by colleagues from Bangladesh, Nepal, and Jordan. We had all gathered in Naivasha, Kenya, to explore how skills in facilitating foresight can be used to help bring about food systems transformation.

The fascinating work these young leaders are involved in and their deep interest in understanding how to be more effective change-makers was truly inspiring. It was encouraging to see how valuable they found the foresight for the food systems change framework and the associated set of participatory tools for engaging stakeholders.

Participants all came with projects from their own countries where they are keen to use foresight and systems thinking to help facilitate change in food systems by bringing together different stakeholders. The participants were from diverse backgrounds representing policy, the private sector, NGOs, and academia.

A Guiding Framework: During the workshop we introduced participants to an overall guiding framework for facilitating foresight for food systems change. A range of participatory tools were used for systems analysis, development of future scenarios and exploring systemic interventions. To bring reality into the workshop, the Kenya horticulture sector was used as a case study for the foresight analysis. Participants spent a day visiting horticulture farms, packing and processing facilities and the local market. They explored with local stakeholders how they saw the future for the horticulture sector and the issues that “keep them awake at night”.

Visualising the system: The workshop was highly interactive with participants practicing in the facilitation of a range of participatory tools which can be used to bring stakeholders into dialogue around systems change. One of my favourite participatory tools “rich picturing”, which enables a diverse group of stakeholders to develop a shared understanding of a system by drawing it, was found by participants to be especially powerful.

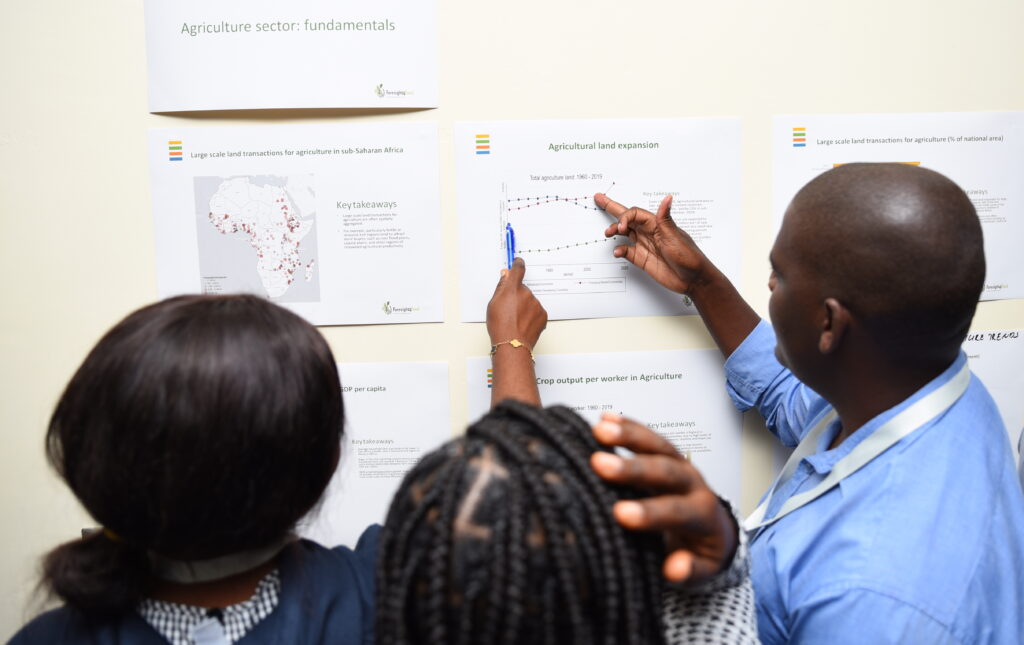

Data-driven dialogue: To go deeper into the systems analysis it is valuable for stakeholders to explore the available data on key drivers and trends. Over 100 graphs visualizing key data points related to the Kenya horticulture sector and food systems at national, continental, and global scales were collated and posted around the walls. The participants then explored this data in groups of three and discussed its implications and how it perhaps challenged their existing assumptions.

Exploring the future using scenarios: Central to the foresight approach is developing a range of different plausible future scenarios (generally with a 10 to 30-year horizon) for how the system might evolve given critical uncertainties. Workshop participants did this for the horticulture sector, looking at factors such as how diets might change in the future, regional and global trading relations, severity of climate change, and the enabling policy environment for small-scale producers and the small- and medium-scale enterprises (SME) sector. The scenarios help to identify future risks and opportunities for different stakeholder groups and society at large. They also help to unlock creative thinking about how to “nudge” systems towards more desirable futures and away from less desirable ones.

The deeper issues of systems change: It is easy to talk about systems change. In reality trying to change systems bumps into all the difficult issues of vested interests, power relations, ideologies, and deeply held cultural beliefs. On top of this human and natural systems are complex and adaptive and behave in self-organising, dynamic, and often unpredictable ways. It doesn’t mean you can’t intervene to try and bring positive change. But it does mean that top-down, linear, and mechanistic models of change generally don’t work. The workshop engaged participants in deep and challenging discussions about what it means to be a leader of systems change. This included the need to be adaptive, how to create alliances for disrupting existing power relations, the importance of building relations between diverse stakeholders, and the importance of patience. Systems change often requires taking time to build the foundations for change without being able to know when circumstances might suddenly unlock opportunities for big steps forward.

Identifying directions for change and intervention options: Developing directions and pathways for systems change is the most difficult and challenging part of the foresight for systems change process. It is highly context-specific and requires a deep insight into the political economy of the situation. Cause and effect mapping, theory of change thinking, and causal loop analysis can all help in identifying opportunities for intervening which could help to drive systems change in desired directions. Bringing change will often require an integrated approach to technological, institutional and political innovation. During the workshop causal loop diagrams were used to explore possible entry points for shifting horticulture systems in ways that could improve health, livelihoods and the environment.

New friends, new networks and big ambitions: After an intense week of learning and sharing participants left inspired to apply the foresight approach back in their own work environment. New friends were made and there were clear calls to find mechanisms to support ongoing networking and peer support.

Many thanks to the facilitation and support team who made a fantastic week possible, Gosia McFarlane, Marie Parramon-Gurney, Kristin Muthui, Bram Peters, Joost Guijt, Riti Herman Mostert, and Abdulrazak Ibrahim. The event was made possible by support from the Mastercard Foundation.

More information about the Foresight4Food Framework of Foresight for Food Systems Change can be found on our website, and an updated approach paper will be published in January 2024.

By Jim Woodhill, Lead Foresight4Food Initiative

A dramatic and rapid transformation of food systems is necessary to end poverty and hunger, protect the environment, improve rural livelihoods, and ensure resilience to future shocks. This transformation must include structural changes in how our political, economic, social and technological systems function. Such transformative change requires a long-term perspective and understanding of the risks and opportunities in different possible food system futures – the purpose of foresight.

Foresight and Food Systems

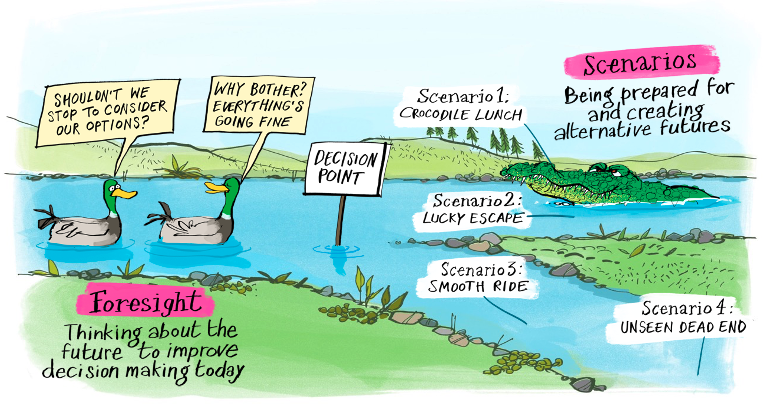

Foresight offers one approach to support transformational change for a more equitable and sustainable global food system. It uses futures thinking and scenario analysis to help diverse food system actors (e.g., rural farmers, food manufacturers, small agri-food businesses, governments) imagine, together, how the future might unfold. Considering future scenarios enables possible risks and vulnerabilities to be understood and mitigated. It also enables opportunities for positive food systems transformation to be identified and explored.

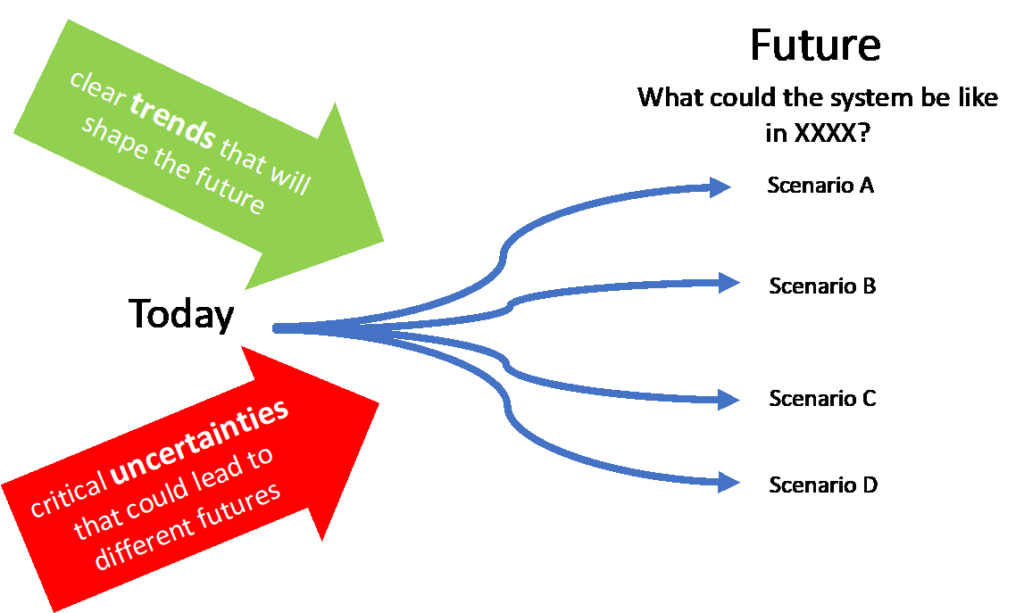

Foresight analysis helps to create understanding about how key trends and critical uncertainties (e.g., changing diets, climate impacts, demand for certain foods) could impact food systems. It supports preparedness for different possible futures.

Food systems are extremely complex, with all of the activities of food systems from production to consumption affecting global health and nutrition, environmental sustainability, and livelihoods and employment. Globally, agri-food work is the largest economic sector, employing over a quarter of the world’s workers. The scale alone of global food systems makes achieving change complicated and slow. Fear of the unknown, combined with vested interests of powerful food systems players, can bring resistance to innovation and change. This results in a lack of effective responses to already pressing issues. The challenge Is compounded by the difficulties of creating sufficient collective understanding and commitment among the highly diverse groups involved in food systems.

However, while change often seems slow and difficult, stuck or even regressing, there are endless positive examples of individuals, communities, groups and organisations working for more sustainable and equitable food systems. Especially when the life force of food is involved, people are deeply capable of innovation, creativity, social organisation and activism.

However, while change often seems slow and difficult, stuck or even regressing, there are endless positive examples of individuals, communities, groups and organisations working for more sustainable and equitable food systems. Especially when the life force of food is involved, people are deeply capable of innovation, creativity, social organisation and activism.

While foresight and scenario analysis is no panacea to the complex and overlapping issues within our food systems, it offers two critical contributions:

- Motivation and clarity for change by offering stakeholders a window into the future, through which they can see how their longer-term interests and aspirations would be affected by different future scenarios.

- Helping break down the barriers of vested interests by facilitating stakeholders to collectively explore options and pathways for change that can balance individual and common interests.

The Foresight4Food Approach

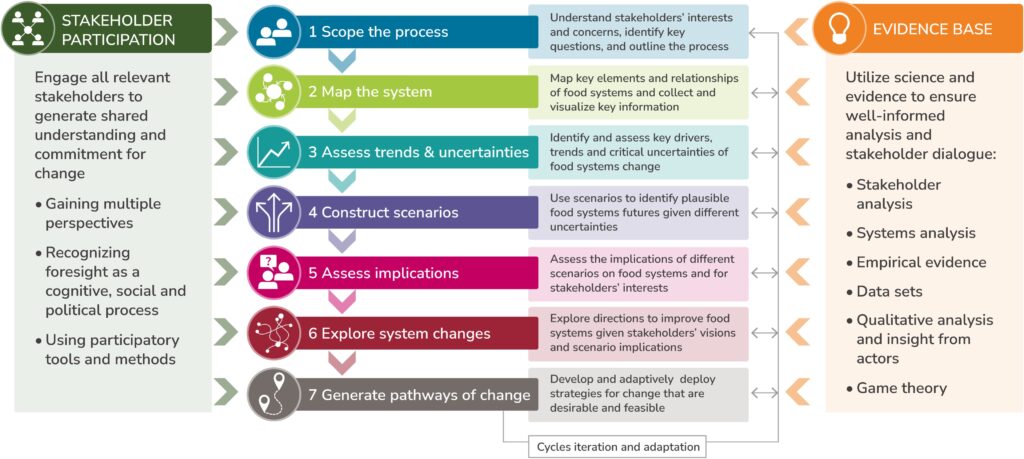

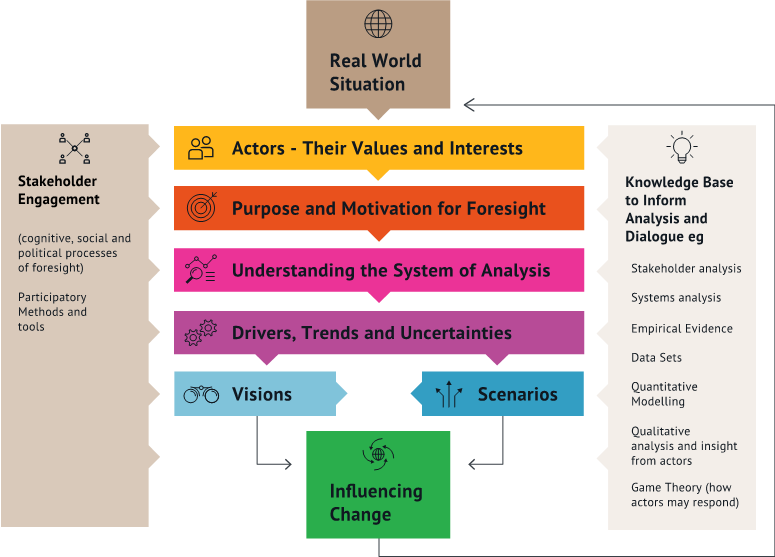

The Foresight4Food Initiative has developed a framework and process to guide foresight and scenario analysis for food systems change. The framework (Figure 1) links a participatory process of stakeholder engagement with a strong scientific evidence base and the use of computer-based modelling and visualisation. The approach starts by understanding how food system actors “see” the food system – their actions, values and interests – and their motivation for engaging in foresight. It maps out and examines how social, technical, economic, environmental and political (STEEP) factors interact within food systems, and how food systems are influenced by the power dynamics between actors.

A food systems framing is critical to identify and assess key drivers, trends and uncertainties, to develop alternative future scenarios (Figure 2). The approach creates dialogue between stakeholders about their assumptions on how the future food system may unfold and what this implies for their visions and aspirations. The discussions that ensue provide a foundation for exploring what directions for food systems change would be in the collective interest and how trade-offs or synergies between the specific interests of different groups can be best managed.

Central to this approach is the development and analysis of future food system scenarios, based on data about key trends and critical uncertainties. This is often the most challenging yet insightful part of the process. It takes various actors ‘outside the box’ to imagine how the future of food systems could be fundamentally different, with what implications.

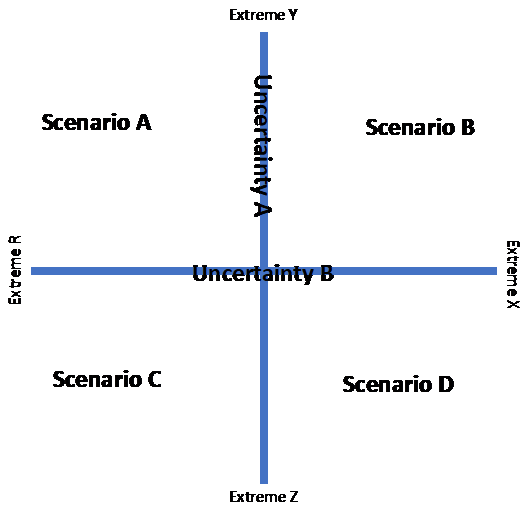

A simple way to develop scenarios is to identify two independent critical uncertainties that then create a matrix of four different scenarios (Figure 3). For example, critical uncertainties in food systems could be dietary changes, climate impacts on agricultural production, malnutrition levels, market and trade functioning, and many others. Scenario story lines are then developed that outline what each of these four futures would be like, based on the two chosen uncertainties. ‘Back casting’ is used to look backwards from an imagined future scenario to construct the possible events and decisions that could have led to such a future.

The framework integrates four elements:

- A futures orientation that invites stakeholders to develop a longer-term perspective on how food systems may unfold in the future, and what decisions are needed today to avoid future risks and build resilience into our food systems.

- Ways of thinking about how change happens in food systems – by linking theories and schools of thought on complex systems, socio-technical transitions, wicked problems, anticipatory governance, cognition, and human bias.

- Practical methods from strategic foresight, scenario planning, multi-stakeholder processes, soft systems analysis, and theory of change.

- Participatory tools for analysis and group facilitation, which enable food system actors to collectively analyse situations and data, create scenarios, engage in dialogue and critical conversations, build trust, and generate pathways of action.

Rethinking Food System Change

Foresight4Food’s approach recognises that elements in the system (i.e., people and nature) interact in complex and adaptive ways; therefore, change in food systems does not occur in easily predicable or linear and hierarchically controlled ways. The complex nature of food systems deeply challenges reductionist mindsets that continue to dominate in public policy making and organisational management. Food systems thinking recognises that change happens through nudging systems, rapid experimentation and learning, and scaling niche innovations. It explores how locked in structures and power relations can be disrupted, yet recognises that building the foundations for desired change takes time, with the eventual outcomes and moments of change being uncertain.

Food systems transformation will require ongoing innovation and learning, with strong networks to obtain feedback and decentralised responsibilities for decision-making and action. Real changes in food systems will depend on shifting underlying structures related to power dynamics, relations between different actors, and the mental models of society, leaders and politicians. Foresight and scenario analysis can help to surface and examine these dimensions of change in a complex and adaptive food system. It is an approach to help generate the critical thinking, leadership and stakeholder engagement needed for food systems transformation.