The Foresight4Food FoSTr programme has been working in Jordan to strengthen national capacity for food systems foresight and transformation. Through a participatory approach, the initiative brings together policymakers, researchers, and local stakeholders to explore future pathways for a more resilient and sustainable food system.

This blog shares insights and reflections from Walid Abed Rabboh, Facilitator FoSTr Jordan, on the lessons learned, challenges faced, and opportunities ahead.

Read Also: FoSTr Jordan Final Country Report

Take a look at the Foresight4Food FoSTr Jordan Final Country Report to learn about the work and findings emerging from the experience in Jordan.

The report outlines Jordan’s comprehensive journey through the Foresight for Food System Transformation (FoSTr) programme, which aims to support national efforts to build a more resilient, equitable, and sustainable food system.

Exploring the Future of Food Systems in Jordan: Lessons from the Foresight4Food Journey

Foresight isn’t just about predicting the future, it’s about shaping it. Through the Foresight4Food FoSTr programme, Jordan embarked on a journey to envision and prepare for the future of its food systems. As part of this process, facilitators, researchers, and policymakers came together to map possibilities, explore scenarios, and imagine pathways toward more resilient and sustainable food systems.

Exploring Scenarios: A Turning Point in the Process

Among all the stages: scoping, mapping, exploring scenarios, and mobilising for change, the scenario exploration phase stood out to me as the most transformative. It was during this stage that data, modelling, and dialogue converged. By bringing evidence to the table and encouraging open conversations, participants were able to co-create shared visions for Jordan’s food future.

This process helped stakeholders navigate trade-offs, identify opportunities, and build consensus around priorities for action. In many ways, it turned abstract challenges into tangible insights and collective understanding, making it both analytical and collaborative.

Engaging Stakeholders: Commitment and Collaboration

From the outset, Jordan’s foresight journey was characterised by strong stakeholder engagement. Ministries, researchers, farmers, and private sector actors all played active roles.

While managing different levels of experience and expectations proved challenging, the outcome was gratifying. The Government of Jordan, in particular, showed remarkable ownership and commitment. Their decision to involve senior officials and even extend the conversation to regional partners demonstrated a powerful belief in the value of foresight for shaping national and regional food agendas.

Foresight as a Mindset for Change

One of the most meaningful insights gained from this experience is that foresight is more than a set of tools—it’s a mindset. It encourages forward thinking, long-term planning, and proactive decision-making in the face of uncertainty.

The biggest challenge, however, lies in sustaining the momentum. Ensuring that foresight becomes a regular part of planning and policymaking in Jordan requires continued effort, institutional support, and capacity-building. But the foundations are now in place for this cultural shift to take root.

The Power of Multidisciplinary Collaboration

Working alongside researchers, facilitators, and policymakers was both inspiring and enlightening. The diversity of perspectives revealed the true complexity of transforming food systems. It also highlighted the importance of developing Jordan-specific foresight guidelines, building a national database of trends, and training local facilitators to maintain and expand this work.

Looking Ahead: A Future-Ready Food System

Foresight and futures thinking will continue to play a central role in shaping Jordan’s food systems in the years ahead. They provide the vision and structure needed to coordinate across sectors and build resilience in an uncertain world.

In practical terms, foresight can help Jordan by:

- Strengthening institutional and individual capacities

- Improving access to data and trend analysis

- Turning opportunities into action and reducing risks

- Supporting evidence-based policymaking

- Enhancing preparedness and resilience

- Promoting regional cooperation

Ultimately, foresight offers more than a strategy, it offers hope. It empowers Jordan to anticipate change, adapt wisely, and co-create a food system that is not only resilient but future-ready.

By Bram Peters

Food systems are at a major transition point as accelerating forces like climate change, shifting shared realities, and growing uncertainties in global trade, AI, health, and the environment shape urgent questions, especially in Kenya, where concerns about the cost of living, democracy, and youth voices are rising.

These uncertainties were the focus of a two-day foresight and systems-thinking workshop at the Kenya School of Government in Nairobi, where 40 national and county-level stakeholders came together to explore the question: how can foresight be activated to catalyse Kenya’s food system transformation process?

The workshop focused on sharing experiences with using foresight for food systems change in Nakuru and Marsabit Counties and was facilitated by Foresight4Food, together with partners Results for Africa Institute, ILRI, University of Nairobi and Society for International Development. It sought to unpack the challenges and opportunities facing Kenya’s food system transformation process and identify key areas where foresight can reinforce connections across scales and build on key models that can help national transformation pathways.

Keynote Insights: From Crisis to Permacrisis

In her opening keynote, Dr. Katindi Sivi emphasized the need for anticipatory policy as Kenya is moving from crisis to polycrisis to permacrisis. Multiple shocks collide, including debt stress, climate change, food insecurity, youth unemployment, and technological disruption. She highlighted key challenges that affect food system governance:

- Fragmented ministries (e.g., agriculture, water, roads, lands, environment) work on different timelines, weakening coordination.

- Government structures are too linear, slow, and siloed to handle interconnected risks.

- Policies often address yesterday’s problems instead of emerging ones.

Foresight provides a framework to: identify weak signals early, prepare for a range of plausible futures, build resilience into public institutions, improve policy coherence across sectors and ensure stewardship for future generations.

This is an urgent challenge, and it must be a priority, especially for public civil servants tasked with guiding governance. This message was echoed by Professor Nura Mohamed, Director General of the Kenya School of Government, who emphasized the critical need to invest in strategic foresight for driving public service reform in Kenya. He also pointed out the need to move from a tendency to ‘celebrate the intention’ to actually implementing the policy frameworks that exist.

The Role of Foresight in Governance

A closer look at process challenges shows that all stakeholders have a role to play, with counties offering important lessons. Key issues needing urgent attention include:

- Policy frameworks are strong but poorly coordinated: Counties like Nakuru and Marsabit use solid planning tools, but overlapping mandates and fragmentation slow progress.

- Blended finance works but must be locally grounded: Nakuru’s County Revolving Fund shows potential, offering affordable loans in partnership with local banks.

- Stakeholder ecosystems are rich but underused: Many actors—from county departments to universities, NGOs, and development partners—need clearer role mapping to reduce duplication and boost collaboration.

- Public participation is essential: Marsabit’s grassroots processes—ward-level engagement and community-led budgeting—strengthen legitimacy and local ownership.

- The research-to-action gap persists: Research often remains unused; living labs, innovation hubs, and university incubation centres are key to translating evidence into practice.

The Kabazi Foresight Innovation Model

A core discussion revolved around the opportunity to learn from the Kabazi Foresight Innovation Model, which has now been piloted in Nakuru and Marsabit throughout the FoSTr programme. Kabazi Ward Innovation Model shows how local food systems stakeholders and communities can work at Kenya county level to offer a locally rooted decision-support ecosystem. This model integrates systems thinking and foresight approaches with a multi-stakeholder partnership approach energised by community leadership. Named after the Kabazi ward in Nakuru, the central idea is to empower and leverage pre-existing Beyond 2030 Networks. These comprise ward departments, chiefs’ forums, school heads, women’s groups, local businesses, and community actors as the foundation for co-creation and systemic change towards a better food system future. This model can be replicated in any county in Kenya.

Workshop Recommendations for Food System Transformation

At the end of the workshop, participants agreed the following:

- Continue to strengthen and build a networked community of practice, integrating foresight, food systems change and facilitation to support Kenya’s food system transformation process

- Strengthen capacity building and communication materials on systems thinking and foresight, especially with the Kenya School of Government and key learning institutes

- Consolidate and scale the county-level ‘Kabazi Foresight Innovation Model’ to share experiences with other counties and support decentralised governance

- Invest in local learning ecosystems such as Community Research and Living labs to support locally embedded and applied sustainable innovation and farmer-centric learning

- Support legislators to adopt a futures perspective when it comes to laws and regulations, such as through the Senate Futures Caucus

- Work towards societal mindset shifts, behaviour change and accountability mentality. The participants noted that value cultivation is crucial for long-term change: values such as responsibility and awareness of food systems must be cultivated, while addressing entrenched social norms that stop us from reframing power and relations within the current food system

Voices of Change: The Power of Spoken Word

The session was enlivened by the spoken word performances of Dorphanage, who artfully captured the deep urgency for change but also reminded participants of the deeply political nature of food systems transformation.

Governments speak of empowerment

While selling futures to foreign hands

Signing away tomorrow for the comfort of today

Pretending not to see the blight they sow

Africa does not lack muscle or mind

Only the will to honor its own abundance

Our fields are fertile with potential

But the plow is steered by self-preserving hands

By Mohammad Monirul Hasan, Facilitator Foresight4Food FoSTr Bangladesh

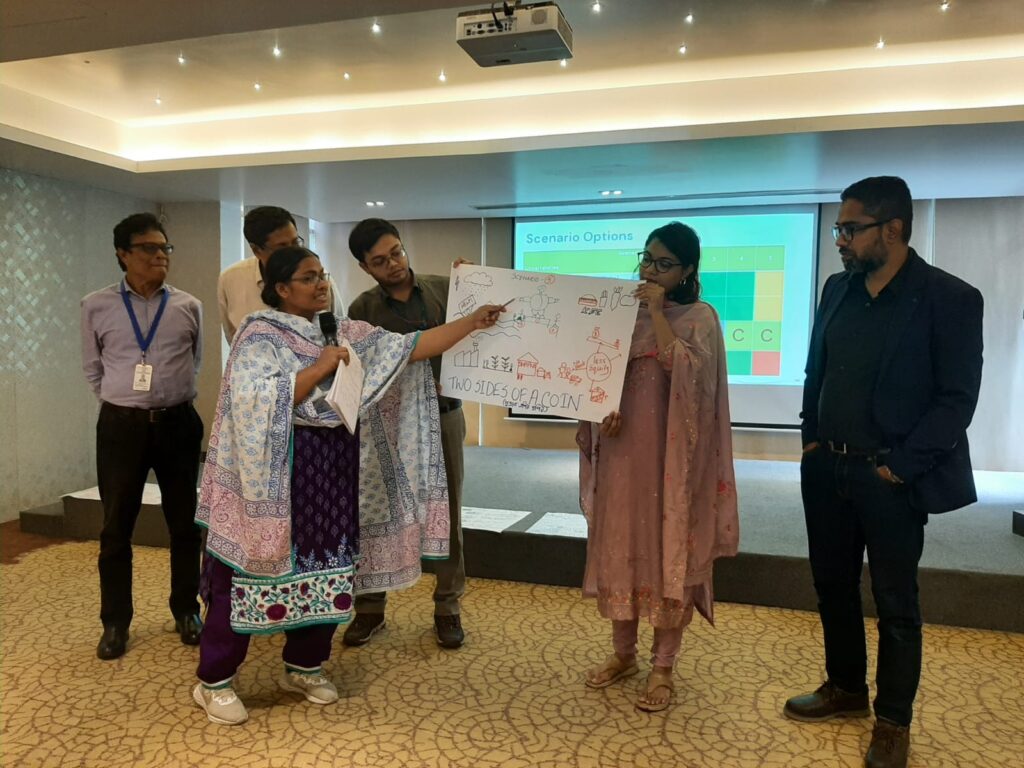

As Bangladesh faces rapid population growth, climate uncertainty, shifting diets, and evolving markets, planning for the future of its food system has never been more urgent. Through the years of the Foresight4Food FoSTr programme, a diverse group of national actors came together to imagine what Bangladesh’s food and nutrition landscape could look like in the decades ahead. It revealed not only the power of collective insight but also the growing momentum for foresight-driven transformation across the country. Mohammad Monirul Hasan, Facilitator Foresight4Food FoSTr Bangladesh, shares his observations on FoSTr programme’s activities in Bangladesh.

Read Also: FoSTr Bangladesh Final Country Report

Take a look at the FoSTr Bangladesh Final Country Report to learn about the work and findings emerging from the experience in Bangladesh. The report outlines Bangladesh’s comprehensive journey through the Foresight for Food System Transformation (FoSTr) programme, which aims to support national efforts to build a more resilient, equitable, and sustainable food system.

Scenario Exploration: A Window into Possible Futures

From what I’ve observed, among the many steps in the foresight process, scenario exploration stood out as the most transformative. It pushed stakeholders to think beyond immediate priorities and consider how climate change, demographic shifts, technology, and politics might shape Bangladesh’s food system. These scenarios helped spark conversations that rarely occur in routine policymaking, encouraging deeper reflection on long-term risks and opportunities, trade-offs, and the cost of inaction. Many participants from our workshops were left with a clearer understanding of how today’s decisions can shape tomorrow’s resilience.

Engaging Stakeholders: Successes and Gaps

The process brought together a wide range of actors, from ministries and universities to business chambers, youth groups, and development partners. This diversity helped build trust and create a shared understanding of the interconnected challenges affecting food security.

However, this experience also highlighted gaps. One of the biggest challenges was the underrepresentation of grassroots voices, like farmers, traders, and local entrepreneurs. Similarly, high-level policymakers were not always present. In addition, some participants needed more time to familiarize themselves with foresight tools, limiting how deeply certain concepts could be explored. Despite these challenges, the workshops succeeded in fostering collective ownership of key insights.

Learning Through Collaboration

What I found truly enriching in the workshops was working in a multidisciplinary environment. Each group brought its own lens, be it economic, agricultural, nutritional, climatic, or governance-related, which revealed the complex interdependencies across the food system. This collaboration underscored how fragmented knowledge can be, and how foresight provides a powerful platform for aligning perspectives and bridging research, policy, and practice.

For many workshop participants, this experience reinforced that systems thinking is not just an analytical method but a way to unlock more coordinated and transformative action.

A Growing National Movement for Foresight

The momentum generated through the FoSTr programme is already influencing national institutions. The Ministry of Food has launched its own Foresight Lab, while the Ministry of Agriculture has integrated foresight into its Agricultural Outlook 2050 initiative. Foresight approaches are now reflected in policy documents such as the UNFSS National Pathway’s Plan of Action, and even the Cabinet Division is incorporating foresight into its social protection programmes. Universities and research bodies are also beginning to embed futures thinking into their work, expanding the country’s internal capacity for long-term planning.

Why Foresight Matters for Bangladesh’s Future

Looking ahead, foresight will play a critical role in guiding Bangladesh through an increasingly complex food security landscape. In my views, here are some of the things foresight can do for the country’s future:

- Strengthen anticipatory policymaking by helping ministries confront climate risks, price shocks, and dietary transitions before they unfold.

- Improve coordination across government, research, the private sector, and civil society, addressing long-standing fragmentation in food system governance.

- Build institutional capacity through cultivating practitioners skilled in systems thinking, scenario analysis, and strategic planning.

- Support inclusive and climate-resilient transformation to ensure that vulnerable groups remain central in future planning.

Finally, I would once again highlight the importance of foresight, which would offer Bangladesh a practical way to navigate uncertainty and co-create a food system that is resilient, equitable, and responsive to the challenges and opportunities ahead. The FoSTr journey has already shown what is possible when diverse voices come together with a shared commitment: a clearer vision of the future, and a stronger foundation for shaping it.

By Bram Peters

These days, the world is a turbulent place, posing challenges for all food systems stakeholders – and headaches for policymakers. Policy makers, tasked with key responsibilities in governance decisions and policy formulation and implementation, are faced with complex, interconnected and dynamic issues amid political sensitivity and ambiguity. How to be a 21st-century policy maker in the Arab region and in Jordan, when reacting is not enough, and transformation is the goal?

Foresight and Systems Thinking

In the face of these challenges, systems thinking and foresight are emerging as key approaches shaping anticipatory governance and participatory policy design. Embraced by institutions such as the European Union, OECD, and UN system, as well as by leading countries like Singapore, Finland, and the United Kingdom, systemic practice and foresight offer powerful perspectives and options for decision-makers. Today, foresight stands as a discipline that combines data, systems thinking, and stakeholder engagement to strengthen resilience, adaptability, and strategic preparedness in an increasingly uncertain world.

Foresight Workshop

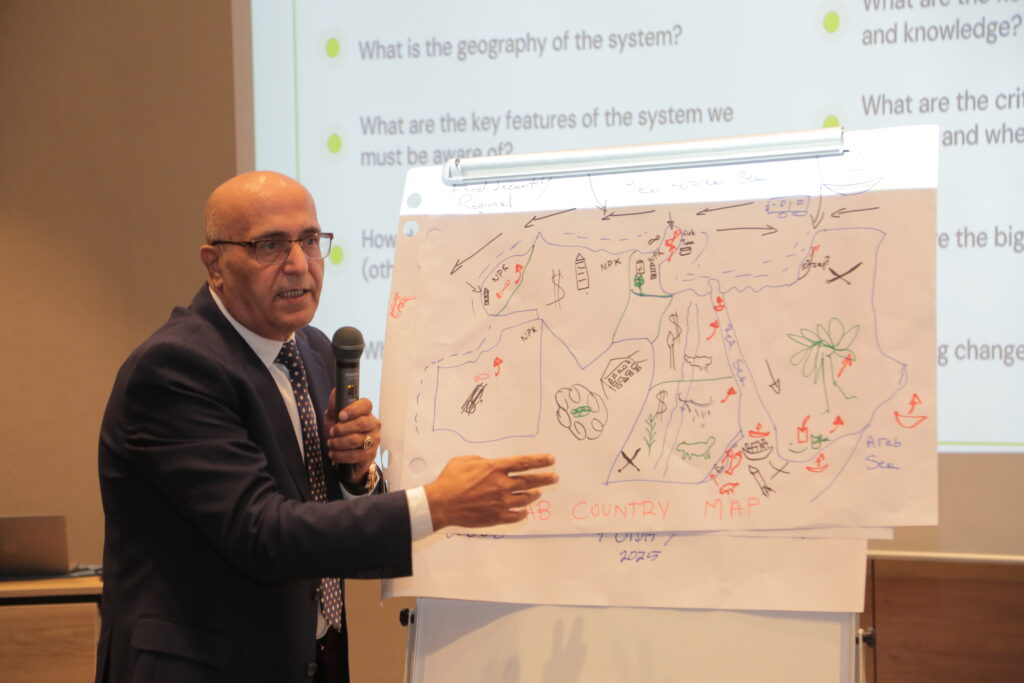

In Amman, 27-29 October 2025, Jordan’s Ministry of Agriculture and Ministry of Planning and International Cooperation hosted an interactive high-level capacity workshop: “Foresight for Systemic Policy-Making”.

Foresight4Food, in collaboration with the National Alliance against Hunger and Malnutrition (NAJMAH) and the Arab Organisation for Agricultural Development (AOAD), facilitated the workshop based on experience supporting Jordan’s food systems transformation process. Over the past three years, the FoSTr Programme, supported by the Government of the Kingdom of the Netherlands through IFAD, in collaboration with the Higher Food Security Council (HFSC) in Jordan, has been working to develop foresight and scenario-building capacities as part of the country’s food system transformation process.

Engagement from the Government

Representatives from more than ten ministries came together – from Education and Finance to Energy, Water, Industry, Transport, Crisis Management and beyond — to explore how foresight and scenario thinking can be used to improve policy making in turbulent and uncertain times. In collaboration with the Arab Network for Agricultural Development, the event also welcomed representatives from Tunisia, Sudan, Lebanon, Somalia, and Yemen – adding valuable regional insights.

The success of the foresight work on food systems sparked interest from other ministries and led to this workshop on how foresight could support integrated policy making across government. Participants explored the future of employment, energy, water, and migration, recognising how these challenges intertwine. Insights emerging included the realisation that, to navigate the future, such collaboration across government is not just helpful — it’s essential. The representatives from other countries enriched the discussions with their experiences and brought a regional perspective while taking home valuable lessons from Jordan.

Participant Recommendations

Participants concluded the workshop by offering 11 recommendations to the Higher Council for Food Security and the Ministry of Planning. These recommendations included, among others, the following key messages:

- It is recommended that ministries and other public institutions integrate foresight and anticipatory approaches into their planning, policy formulation, and decision-support processes.

- National planning authorities or their equivalents should take the lead in identifying and harmonizing common drivers, assumptions and trends.

- The participants recommended organizing a Training of Trainers (ToT) workshop for participants from Jordan and other Arab countries.

- The participants called for the establishment of a national Jordan foresight network, enabling more national capacity building, coordination and regional collaboration.

The Foresight4Food FoSTr Programme in Uganda has been a transformative journey that brought together diverse voices to imagine, question, and shape the future of the country’s food systems.

Charles Muyanja, Country Facilitator FoSTr Uganda, shares his reflections on what made the process meaningful, what was learned, and how foresight thinking is shaping Uganda’s path forward.

Read Also: FoSTr Uganda Final Country Report

Take a look at the FoSTr Uganda Final Country Report to learn about the work and findings emerging from the experience in Uganda. The report presents the findings and process of the Foresight4Food FoSTr programme in Uganda, which applied participatory foresight and futures thinking to help Ugandan policymakers and stakeholders anticipate and shape the long-term transformation of the country’s food system.

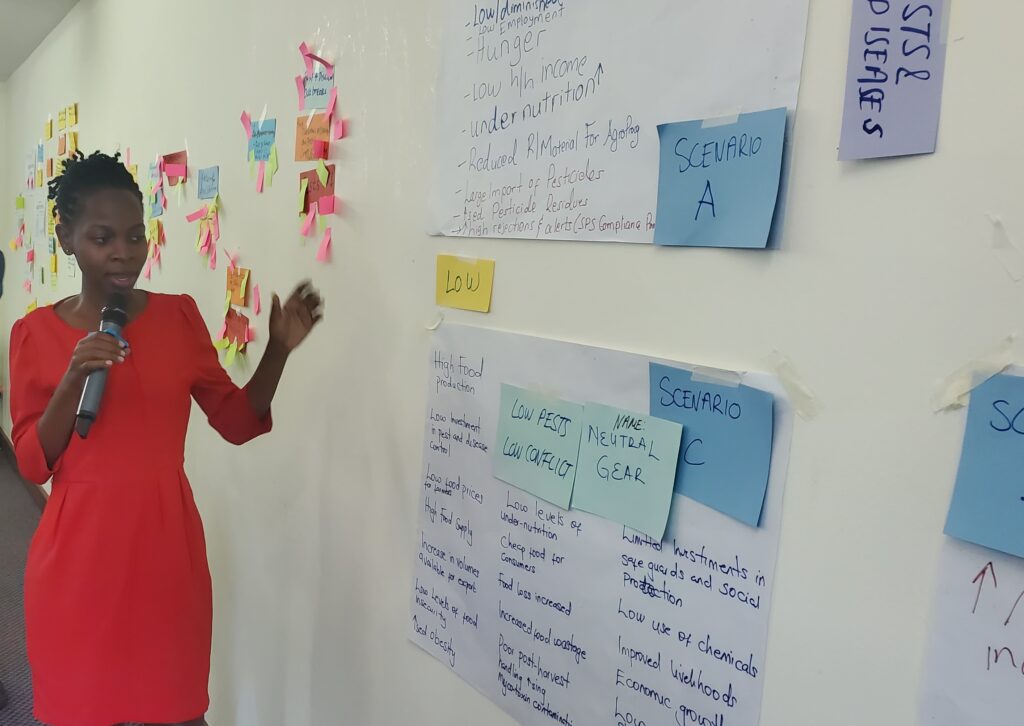

Exploring Scenarios: The Most Insightful Phase

Among the different phases of the foresight process that we worked through, scoping, mapping, exploring scenarios, and mobilising for change, I found that exploring scenarios offered the richest insights for Uganda’s food system.

This stage invited stakeholders to think deeply and critically about possible futures, considering drivers such as climate change, food loss, and waste. By examining various scenarios, they identified key opportunities, risks, and resilience strategies suited to Uganda’s context.

Exploring scenarios was complex, but it helped stakeholders understand the interconnections within the food system, how one element influences many others.

Stakeholder Engagement: Learning, Trust, and Shared Ownership

From my observation, stakeholder engagement was a highlight of the process. Ministries, researchers, farmers, and private sector actors were carefully selected for their relevance and passion for transforming Uganda’s food systems.

Their involvement was structured and participatory, promoting shared learning and ownership. Moreover, capacity-building workshops, conducted under the Foresight4Food FoSTR programme, played a key role in equipping participants with practical knowledge on food system transformation, which many could immediately apply in their workplaces.

The greatest success was the knowledge imparted, helping stakeholders see transformation as a collaborative process.

However, in this process, challenges also surfaced. Some participants initially viewed monetary incentives as more valuable than knowledge. There were others who struggled to stay consistent across all workshop sessions. In my experience, encouraging commitment and continuity required a lot of patience and persistent engagement.

Personal Learning and Growth

For me, the project was a meaningful learning experience in teamwork and collaboration. Working with a multidisciplinary team of researchers and facilitators strengthened my appreciation for collective effort and coordination.

In my position as the Country Facilitator, I also gained deeper insight into the power of foresight as a decision-making tool, one that enables leaders to anticipate challenges and act proactively rather than reactively.

Yet, it wasn’t without its hurdles. The hardest part was helping stakeholders understand the value of foresight in their work. Without that appreciation, sustained engagement was difficult. Managing expectations, especially regarding finances, also demanded careful communication and diplomacy.

Power of Multidisciplinary Collaboration

Working alongside researchers, policymakers, and facilitators gave me a new appreciation for the complexity of food systems and the importance of systems thinking.

I saw firsthand how different disciplines could come together to create holistic solutions, bridging science, policy, and community perspectives. Facilitators also played a crucial role in translating technical ideas into accessible insights, ensuring all participants could meaningfully contribute.

This inclusive approach empowered stakeholders as resource persons and promoted learning through shared experience. Food system transformation requires engagement with stakeholders from different sectors incorporating their local perspectives and indigenous knowledge into foresight approaches and methods, which is vital for strengthening the food system analysis and fostering implementation of the of proposed strategies.

Looking Ahead: Foresight as a Pathway for Transformation

Foresight and futures thinking will continue to be a cornerstone for Uganda’s food system transformation in the years ahead. By supporting proactive, strategic, and adaptive approaches, foresight helps identify potential risks, such as climate change, resource scarcity, or market disruptions, while also uncovering emerging opportunities like technological innovation and new policy frameworks.

Futures thinking will provide the Government of Uganda with a well well-structured way to evaluate different scenarios, helping policymakers prioritize investments and formulating policies that promote resilience and sustainability within Uganda’s food systems.

Last but not the least, I’d like to emphasize the importance of building a Community of Practice (CoP) that brings together diverse stakeholders including local communities and policymakers, to continually reflect, research, and act on the future of food in Uganda.

Foresight helps us move from reaction to preparation. It gives us the tools to imagine better futures, and the courage to make them happen.

By Jim Woodhill and Bram Peters

We’re excited to launch our new guide: “Using Foresight for Food Systems Transformation – A Guide for Policymakers, Practitioners, and Researchers.” Developed collaboratively by the UN Food Systems Coordination Hub and Foresight4Food, this guide is being released today to coincide with the UN Food Systems Summit +4 Stocktake (UNFSS+4), taking place in Addis Ababa, Ethiopia, from July 27 to 29.

Why This Guide Matters

Transforming food systems to ensure better health, greater equity, and environmental resilience demands future thinking. We must collectively envision how our food systems can evolve—and confront the risks of “business as usual.” Anticipating future shocks and stresses can help drive proactive policy, investment, and innovation before crises hit.

This guide is a hands-on resource for applying foresight and scenario analysis at national and local levels to accelerate food systems transformation. It demystifies the basics of foresight, lays out practical steps for launching a foresight process, and offers real-world examples and curated resources.

What You’ll Find in the Guide

- Clear explanations of foresight and scenario analysis methods

- Step-by-step guidance for facilitating participatory foresight processes

- Insights and tools drawn from the global Foresight4Food network

- Case examples illustrating how foresight is being used in diverse contexts

At the heart of this approach is bringing together diverse stakeholders—from farmers and consumers to policymakers and private sector actors—to build shared understanding, trust, and momentum for collective action.

Part of a Broader Set of Resources

This new guide complements the Foresight4Food “Foresight for Food Systems Change Process Guide & Toolkit”, which dives deeper into participatory tools and techniques for systems mapping and scenario building.

It also aligns with new resources like FAO’s “Transforming Food and Agriculture through a Systems Approach”, which supports systems thinking for transformation. In parallel, Alliance Biodiversity and CIAT are highlighting the importance of subnational stakeholder engagement as a critical entry point for change.

A Call to Action

Transforming food systems will require significant investment—but more importantly, it needs broad-based commitment. Consumers, producers, businesses, and political leaders must be aligned on the necessary changes and the trade-offs involved. That means shifting mindsets, creating political will, forging new alliances, and rebalancing power.

As we move beyond the UNFSS+4, we need renewed focus on investing in high-quality, inclusive stakeholder processes. The foresight approach outlined in our new guide offers a powerful pathway to doing just that.

The 5th Global Foresight4Food Workshop was scheduled to take place from June 15 to 19, 2025, in Jordan. Preparations were in full swing, with the Foresight4Food team and partner organizations working diligently to create a seamless and impactful gathering.

However, on June 13, just as our team was preparing to travel to Jordan, a sudden escalation in the regional conflict—marked by an Israeli strike on Iran—led to the closure of Jordanian airspace. Within hours, the months of planning came to a screeching halt, and the difficult but necessary decision was made to cancel the workshop in the interest of participant safety.

The 5th Global Foresight4Food Workshop had drawn robust international interest, with confirmed delegates from 33 countries across different continents. The agenda promised rich discussions on foresight tools, collaborative learning, and systemic approaches to building resilient and equitable food systems worldwide. Moreover, many participants were preparing to share interesting cases from their respective projects/ regions, which were to be presented at the workshop. Had the workshop unfolded as intended, it would have provided an invaluable platform for in-depth dialogue and collaboration among global experts.

The Importance of Foresight in Times of Uncertainty

This situation is a powerful reminder of why foresight is essential—not only as an approach for future preparedness but as a mindset. Food systems today are increasingly influenced by global disruptions, from geopolitical instability to climate shocks. The abrupt cancellation of this event, due to an unforeseen military escalation, illustrates the fragility of international coordination and the importance of preparing for uncertainty. Foresight helps us map out plausible futures, stress-test strategies, and design systems that can adapt—not just react—to change. In moments like this, its value becomes especially clear.

Gratitude to Our Partners and Participants

We extend our deep gratitude to our Jordanian partners, whose dedication and hospitality have been extraordinary. Our thoughts are with them and with all those affected by the ongoing regional crisis. We also thank our global participants for their understanding, flexibility, and continued commitment to this shared mission.

Looking Ahead: Alternative Plans to Keep the Momentum Going

While the in-person workshop cannot proceed as planned, our work continues. The Foresight4Food team is actively exploring alternative formats to carry forward the goals of the workshop, including virtual sessions and co-creation trajectory, and hybrid brainstorming sessions. We remain committed to maintaining the momentum and fostering the global collaboration that this initiative represents.

We are preparing a range of new and exciting events:

- Radical food systems futures co-creation trajectory, including

- Inspiring case presentations

- Radical futures exploration

- Co-creation of radical food system futures

- Regional foresight hub brainstorming sessions

- Hybrid engagement on foresight, institutional embedding and food systems

- Hybrid conference in Oxford in September 2025

In addition, we are exploring options to hold a hybrid session in Jordan to support regional food systems transformation through foresight.

Watch our website and LinkedIn page for updates on future plans and opportunities to engage. Foresight4Food’s mission to support better-informed, inclusive, and strategic decisions for the future of food systems continues—stronger than ever.

By Bram Peters, Food Systems Programme Facilitator

The future is a mystery, full of uncertainties, risks and opportunities. Yet, humans and human systems have a remarkable ability to turn imagination into reality. In this landscape of uncertainty, foresight becomes an essential tool, helping us navigate what lies in the future. This is especially important when it comes to food systems transformation.

In this blog, I will endeavour to give you a glimpse at how foresight, awareness of the political nature of futures, and alternative scenarios can help us rethink and reshape our food systems for a more just and sustainable future.

Four Ways to Think About the Future

According to Muiderman et al. (2020), there are four main approaches to foresight:

- Assessing Probable (and Improbable) Futures

Example: The IPCC climate scenarios, which predict likely outcomes based on different climatic and environmental trends, and possible climate actions. - Contending with Multiple Plausible Futures

Example: Scenario matrices that explore what could happen in different situations under various combinations of uncertainties. - Imagining Diverse, Pluralistic Futures

Example: Visioning exercises where we picture a desired future, then work backwards (backcasting) to figure out how to get there. - Scrutinizing the Performative Power of Future Imaginaries

This approach examines how our collective visions of the future can actually shape reality.

Most foresight work focuses on the first three approaches. But in today’s world, shaped by pandemics, global conflicts, and rising political tensions, having the skills to apply the fourth approach can be considered to be more important than ever. A recent Synthesis Review of food system futures conducted by Foresight4Food identified that we can generally see various clusters of key food systems futures around ‘business as usual’, ‘global sustainability’,

‘local solutions’, ‘rising inequalities’, and ‘uncontrolled chaos’. However, it was also observed that none of these described scenarios portray very radically different food system futures.

The Power of Collective Imagination

Jasanoff and Kim, in their book Dreamscapes of Modernity (2015), introduce the idea of socio-technical imaginaries:

“Collectively imagined forms of social life and social order reflected in the design and fulfilment of nation-specific scientific and/or technological projects.”

In simpler terms, societies tell themselves stories about who they are, where they’ve been, and where they’re going. These stories—these imaginaries— can reshape history, redefine the present, and chart a course for the future. And often, they serve the interests of those in power.

The Future Is Political—and It’s Already Here

Why does this matter? Because the future isn’t just something that happens to us. It’s something that societies seek to actively shape, often through powerful narratives. Consider some current, concerning, imaginaries being promoted by powerful elites:

- Trump’s “Golden Dome” and the slogan “Make America Great Again”

- Elon Musk and other tech company elites’ visions of Artificial General Intelligence

Alternative imaginaries to counter power and transform societies toward a very different future also exist. Think about:

- The Degrowth Manifesto, as proposed by Kohei Saito in his book ‘Slow Down’

- Ministry of the Future, as narrated by Kim Stanley Robinson

Shaping Better Futures—Together

Foresight, when used critically, inclusively and deliberatively, has the power to shape more inclusive and constructive imaginaries. Jasanoff writes that these imaginaries “offers a glimpse into the realities of the known, the made, the remembered, and the desired worlds in which we live—and which we have the power to refashion through our creative, collective imaginings.”

In other words, we can—and should— together imagine alternative, inclusive, sustainable and transformative futures, making them tangible. The time to do this, at scale, is now. The Foresight4Food Global Workshop, taking place in Jordan from 15-19 June, will include an exercise on ‘Radical Food System Futures’. This will harness the collective intelligence of the foresight and food systems community, and enhance focus on imagining very different food systems than we see around us today.

Preparations are well underway for the 5th Global Foresight4Food Workshop set to take place in Amman, Jordan, from 15 to 19 June 2025. This dynamic event will bring together foresight thought leaders, innovators, and changemakers from around the world. Designed to spark dialogue, ignite creativity, and drive tangible progress, the workshop offers a unique platform to advance the global foresight agenda for food systems.

In the lead-up to the event, Asem Nabulsi —Foresight4Food FoSTr Programme Deputy Facilitator in Jordan—shares his perspectives on the critical challenges and emerging opportunities shaping global food systems. In this blog, he offers valuable insights into the urgent need for systemic change and highlights the powerful role foresight can play in building a more equitable, nutritious, and sustainable future.

Beyond the Macro Lens: Reclaiming the Food System Narrative

A critical concern shared by many in the global food space is that the decisions influencing food systems are often made at the macro level, detached from the lived realities of communities and the interconnected outcomes they produce. The fragmented approach overlooks how policies and practices affect health, nutrition, livelihoods, and the environment. Foresight provides the structure to consider these dimensions together, helping stakeholders envision multiple futures and make informed, holistic decisions.

Sharing Real-world Experiences

The success of the upcoming Foresight4Food Global Workshop hinges on more than dialogue—it depends on active participation, sharing real-world experiences, and co-creating concrete, implementable recommendations.

When foresight thought leaders, innovators, and food system stakeholders from around the world sit together, it should not just be about knowledge exchange; it should be about laying the groundwork for lasting change through mutual understanding and collective action.

From Dialogue to Action: Integrating Insights into Practice

I see this global workshop as a springboard to rethink professional strategies. One needs to fully understand the importance of multistakeholder perspectives and collaborative design of actions that consider the full spectrum of affected groups. This approach ensures that decisions are not only visionary but grounded in equity and practicality.

Regional Collaboration: The Untapped Potential

While food systems are often discussed within national borders, I would like to remind you that no country exists in a vacuum. Regional interdependence, from raw materials to trade and market access, necessitates greater collaboration. To build more resilient food systems, I suggest enhancing bilateral and multilateral trade, establishing regional food hubs, diversifying trade routes, and creating supportive regulatory frameworks. These steps could buffer regions against future disruptions and strengthen food sovereignty.

The Leadership Imperative

Leadership is essential for steering transformation. Setting a suitable regulatory environment, mapping the current food system and agreeing on the goals and best way forward to reach the desired goals, fostering a cooperative environment for change, uniting stakeholders understanding and action towards the desired goals, taking the decisions and actions that incentivise actions that enhance positive food system transformation at the different levels and for different stakeholders, raising awareness for all actors affecting and being affected by food systems, creating a national re-iterative process to regularly examine the efficacy of changes made and looking out for changing factors that might affect the food system, and starting the communication and actual practical steps for regional cooperation.

From Vision to Implementation: Making Collaboration Stick

A practical roadmap to ensure the workshop leads to a lasting impact is to focus on the importance of moving from vision to implementation. It means building a shared understanding, defining common goals, and designing actions that are informed by the perspectives of diverse stakeholders across multiple levels. Open discussions around potential trade-offs and strategies to mitigate negative impacts are also key. To translate dialogue into action, I would highlight the need for clear, well-defined plans with assigned responsibilities and timelines. I believe that this structured yet adaptable approach is crucial for fostering durable cross-sector collaboration and meaningful progress.

With these reflections in mind, I look forward to welcoming you in Jordan and seizing this unique opportunity to catalyse both regional and global efforts toward meaningful food system transformation.

By Bhawana Gupta and Monika Zurek

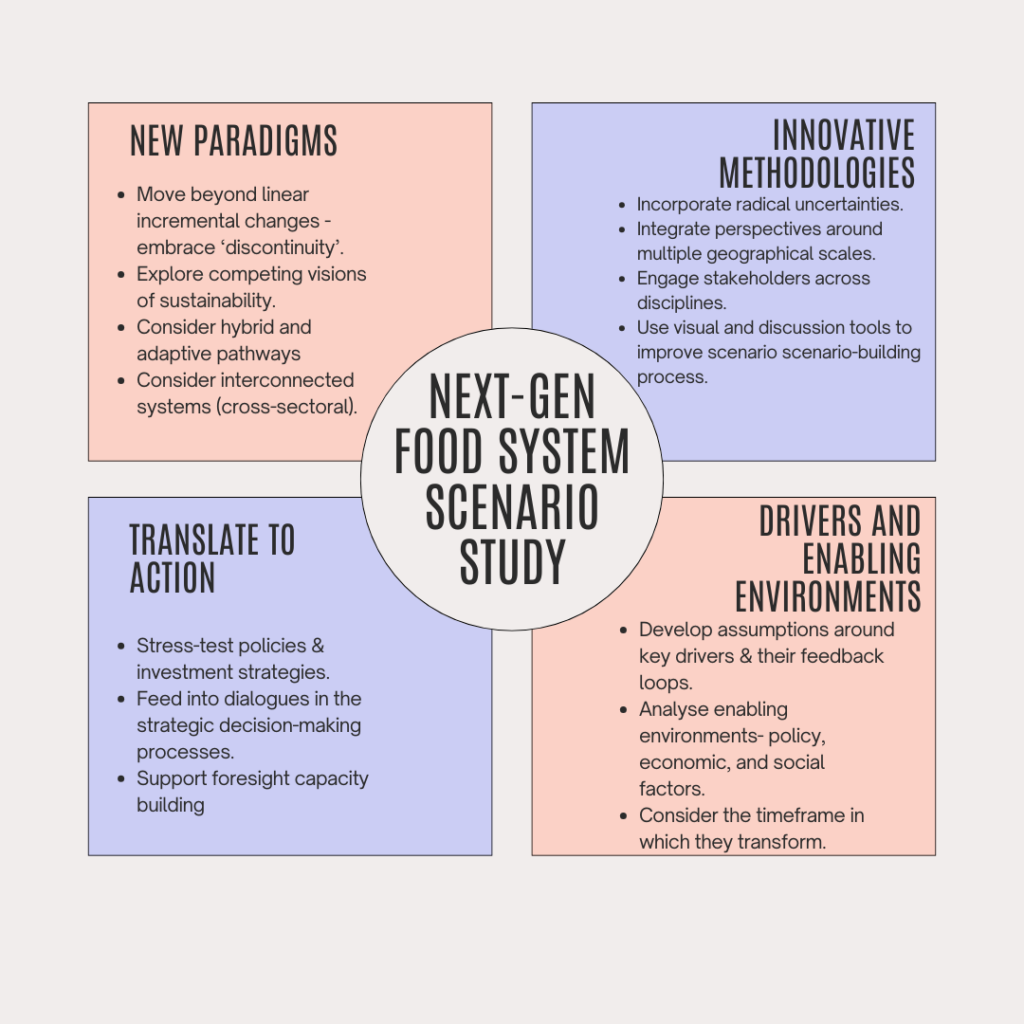

What if the future of our food system looks nothing like what we’ve imagined so far? Our recent report “Food systems of the future” examines how foresight studies are shaping our view of what’s to come. It reveals the urgent need for a new wave of forward-thinking work that dares to imagine fundamentally different food system configurations. Next-generation food system scenarios must embrace a new change paradigm, innovative methodologies, and a clear pathway to incentivise action through a deeper understanding of future drivers and enabling environments.

Why do we need another global-level scenario study?

We live in what many call the acceleration phase of the Anthropocene, an era defined by rapid and unpredictable change. For years, scholars and practitioners across disciplines worked to unravel the complexities of our global food system, using scenarios as vital tools to explore how different forces shape its future. But it’s crucial to remember that these scenarios are not only built on data; our assumptions, beliefs also shape them, and our constantly evolving grasp of the drivers of change[i].

The evolution of food system scenarios reflects this shift. Early models mostly focused on projecting food production and demand based on population growth. Over time, their scope broadened to encompass factors like resource availability, climate change, policy shifts, and socio-economic dynamics. Yet, the turbulent events of the past five years—think of the global pandemic, geopolitical tension, and unexpected supply chain disruption—have shown us that even the most sophisticated scenarios failed to capture certain uncertainties.

Grappling with the multifaceted complexities of the future is undoubtedly a wicked problem. But by continually refining our foresight techniques, we can better prepare for future shocks and proactively design alternative pathways. Let’s explore the critical building blocks for this next generation of global food system scenarios.

1. New paradigms

In Donella Meadows’ view, a paradigm is a shared set of beliefs, values, and assumptions that underlie a system. This core mindset dictates the system’s goals, structures, and operational rules. It follows that a paradigm shift is one of the most powerful drivers of lasting change within a system. For our discussion, there are three aspects that should be considered:

- Discontinuity: Past scenario studies often urged the inclusion of a surprise element or discontinuity[ii] (read box 1 for definition). However, these discontinuities were considered weak in almost all scenarios, especially quantified ones. Instead, scenario studies emphasised continuous incremental changes in the system. Going forward, our scenarios must move beyond a smooth and predictable evolution to explicitly explore non-linear changes, tipping points, and abrupt shifts.

BOX- 1

The term discontinuity is used variously in scenario literature, broadly signifying a sharp departure from past trends caused by high-impact developments, phenomena, and events. The significance of a discontinuity depends on its character, magnitude, speed, and ripple effects, and whether it has been anticipated and ameliorated. Here, a discontinuity refers to a significant shift of social-ecological structure and dynamics, rather than a transient perturbation after which the system reverts to its original trajectory. Related terms are surprises, bifurcation, critical transition, tipping points, tipping elements, wild cards, and black swan events. More recently, the phrase game changers has been introduced for shifts in how society is organized through understandings, values, institutions, and social relationships.

- Mental models: Since the IPCC’s ‘Shared Socio-economic Pathways’, most global scenario studies have relied on a mental model that assumes four broad pathways:

- A sustainable pathway characterised by progressive policy and technological adoption.

- A business-as-usual pathway, projecting a continuation of current trends.

- A collapse or environmental destruction pathway, depicting worst-case outcomes.

- A divided world pathway, where inequalities worsen and cause socioeconomic distress.

While seemingly intuitive the widespread use of this mental model is influenced by cultural biases, cognitive processes[iii], and the culture of scientific reticence[iv] (read box 2 for more). These factors can lead to the design of scenarios that are overly simple, feel intuitively right, and align with common ways of thinking about the future: an optimistic view, a middle ground, and a pessimistic view. We must challenge this reliance on simplistic archetypes and embrace more nuanced and multi-dimensional perspectives in our scenario development.

BOX- 2

Anchoring bias: We tend to rely too heavily on initial information, making it difficult to envision radically different futures.

Confirmation bias: We seek out information that confirms our existing beliefs, reinforcing the status quo.

Incrementalism: We assume change will be gradual and predictable, neglecting the potential for sudden, non-linear shifts.

Lack of interdisciplinary input: Many scenario studies are limited by the perspectives of a narrow range of experts, missing crucial insights from other fields like sociology, ecology, and complexity science.

- Cross-sectoral linkages: Too often, scenario studies operate in isolation, focussing on a single system like food. They fail to incorporate the strong interdependencies with other critical systems such as energy, water, or social systems. This approach can create a lack of understanding of the potential for cascading system failures, or conversely, unexpected positive feedback loops. Future scenarios must explicitly model these intricate interconnections, exploring how changes in one sector can trigger ripple effects across others.

2. Innovative methodologies

Advancing food system scenarios requires leveraging innovative methodologies, for example:

- Multi-scale analysis: Most past food system scenario studies focused on processes at specific geographic scales. Yet food systems operate across a spectrum, from individual households to global markets, with numerous complex inter-dependencies. These dynamics need to be captured in the future studies. The methodology for linking scenarios at different scales was explored by Zurek et al[v]. By integrating local, regional, and global food system dynamics, we gain a more holistic understanding of potential futures.

- Radical scenario development: The scenarios developed in the last decade have often underplayed outlying, surprise, or disaster events[vi]. Yet the inclusion of diverse and radical uncertainties can advance the quality and utility of scenarios[vii]. The development of radical scenarios combines established scenarios with group discussion techniques, as discussed in Talwar et al.[viii]. We need to better embrace wild cards and black swans as integral parts of scenario development, exploring how low-probability, high-impact events can reshape the future.

- Multi-disciplinary expert involvement: Food systems are inherently complex and interconnected, necessitating the involvement of actors across multiple sectors (e.g., agriculture, trade, health, and environment) and governance levels (from local to global). Innovative participatory methodologies such as Transdisciplinary Foresight Labs[ix] and Causal Layered Analysis (CLA)[x] can unpack issues on various levels and uncover underlying assumptions around litany, systemic causes, worldviews, and myths that shape expert opinions. Together, these methodologies support more holistic, inclusive, and imaginative scenario processes.

3. Drivers and enabling environments

Today’s scenarios commonly describe assumptions around the drivers of change (e.g. technological shifts, demand patterns, and trade dynamics). Next-generation studies must go further and reflect on the enabling environments that shape the dynamics of future food system drivers and the timeframe within which the change unfolds. This includes[xi]:

- Policy and governance: How do regulations, institutional capacity, and international agreements shape food system operations?

- Economic and financial structures: How do investment patterns, trade dynamics, and economic inequality influence food access and production?

- Social and cultural context: How do changing consumer preferences, social equity, and cultural norms drive food demand and system practices?

- Technological and infrastructural frameworks: How does digital connectivity, research and development (R&D), and infrastructure development enable or constrain food system innovation?

- Environmental governance: How do policies and practices regarding resource management and climate change impact food production sustainability?

4. Translate to action

Developing next-generation scenarios is not just an academic exercise. To be truly impactful, these studies must bridge the gap between foresight and implementation, ensuring that scenario narratives translate into policy and strategic actions. This involves:

- Using real-world stress tests: Running policies and investment strategies against multiple scenario conditions to assess their resilience.

- Embedding scenario thinking: Integrating foresight and scenario planning directly into decision-making processes at national and global levels. (Read about institutionalising foresight in decision-making in another blog).

- Engaging non-traditional stakeholders: Involving a broader range of voices, including grassroots organizations, indigenous groups, and regenerative farmers, to develop a shared language around food systems and future pathways.

Conclusion

Essentially, the prevailing paradigm in many current scenario studies inadvertently restricts our imagination and limits our collective ability to envision and prepare for truly transformative change. It creates an illusion of control in a world that is far more contingent and unpredictable. The necessary shift towards scenario studies that adequately reflect paradigm shifts is a complex but crucial endeavour, requiring a fundamental rethinking of how we construct and interpret future possibilities.

The food system of tomorrow will not be shaped by predictions, but by our collective capacity to anticipate, adapt, and transform. Advancing next-generation global food system scenarios requires bold thinking, cross-sector collaboration, and an openness to radical possibilities. The question remains: are we ready to embrace this challenge?

[i] Cork, S., Alexandra, C., Alvarez-Romero, J.G., Bennett, E.M., Berbés-Blázquez, M., Bohensky, E., Bok, B., Costanza, R., Hashimoto, S., Hill, R. and Inayatullah, S., 2023. Exploring alternative futures in the Anthropocene. Annual Review of Environment and Resources, 48(1), pp.25-54.

[ii] Rothman, D.S., Raskin, P., Kok, K., Robinson, J., Jäger, J., Hughes, B. and Sutton, P.C., 2023. Global Discontinuity: Time for a Paradigm Shift in Global Scenario Analysis. Sustainability, 15(17), p.12950.

[iii] Cork, S., Alexandra, C., Alvarez-Romero, J.G., Bennett, E.M., Berbés-Blázquez, M., Bohensky, E., Bok, B., Costanza, R., Hashimoto, S., Hill, R. and Inayatullah, S., 2023. Exploring alternative futures in the Anthropocene. Annual Review of Environment and Resources, 48(1), pp.25-54.

[iv] Rothman, D.S., Raskin, P., Kok, K., Robinson, J., Jäger, J., Hughes, B. and Sutton, P.C., 2023. Global Discontinuity: Time for a Paradigm Shift in Global Scenario Analysis. Sustainability, 15(17), p.12950.

[v] Zurek, M.B. and Henrichs, T., 2007. Linking scenarios across geographical scales in international environmental assessments. Technological forecasting and social change, 74(8), pp.1282-1295.

[vi] Gupta, B., Zurek, M.B., Woodhill, J. and Ingram, J. 2025 submitted for publication to Frontiers in Sustainable food systems

[vii] Gordon, D., 2021. Radical Uncertainty: Decision-Making Beyond the Numbers. Quarterly Journal of Austrian Economics, 24(1), pp.206-210.

[viii] https://jfsdigital.org/2019/06/15/the-future-of-energy-reinvented-case-study-of-the-radical-scenario-development-approach/

[ix] Pólvora, A. and Nascimento, S., 2021. Foresight and design fictions meet at a policy lab: An experimentation approach in public sector innovation. Futures, 128, p.102709.

[x] UNDP (2022). UNDP RBAP: Foresight Playbook. New York, New York.

[xi] Gupta, B., Zurek, M., Woodhill, J., Ingram, J. (January, 2025). Food Systems of the Future: A synthesis of food system drivers and recent scenario studies. Foresight4Food. Oxford, United Kingdom.

By Marcos Esau Dominguez Viera, Foresight Modeling Expert, FoSTr Jordan

In early April 2025, I had the opportunity to attend the 10th Global Workshop of the Agricultural Model Intercomparison and Improvement Project (AgMIP10) in Texcoco, Mexico. The event brought together a vibrant international community of researchers dedicated to advancing the intersection of agriculture, climate change, and food systems transformation.

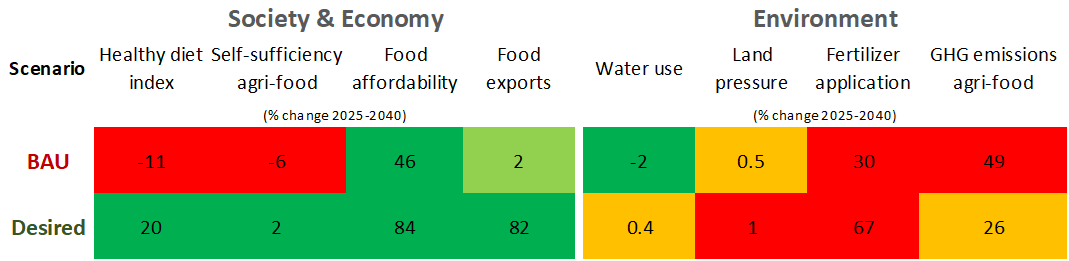

Marking a decade of collective progress, the workshop underscored the growing importance of rigorous, data-driven insights to inform transformative decisions at both local and global levels. In this blog, I spotlight a regional experience presented at the workshop—our work in Jordan, where we integrated quantitative simulation modeling with stakeholder engagement. This approach enabled local actors to explore and envision the potential impacts of diverse future scenarios on their national food system.

Participatory modelling approach for food system transformation in Jordan

Across the global econ modelling community, we are seeing growing interest in deep-dive studies at the country level. In this sense, I had the opportunity to speak at a session on regional integrated assessments of risk and adaptation options. I shared insights from our ongoing work under the FoSTr (Foresight for Food Systems Transformation) programme in Jordan. Over the past three years we’ve combined the power of MAGNET—a global general equilibrium model—with inclusive, participatory foresight approaches in the country. This iterative process brought together data and diverse perspectives to explore two very different scenarios for Jordan’s food system between 2025 and 2040.

I break down these scenarios in more detail below.

Two Futures: Business-As-Usual vs. Desired Transformation

Business-As-Usual (BAU)

- Jordan’s population hits 16 million by 2040

- GDP grows modestly at 2.6% annually

- Agricultural productivity is input-driven (mainly fertilizer use)

- Trade barriers and climate change threaten food security

- A continued shift toward Western diets

Desired Scenario

- Population growth slows (13 million by 2040)

- Regional conflicts do not affect trade

- Climate resilience increases

- Food loss and waste is cut by 50%

- Population shifts to Jordanian Mediterranean diet

What we’ve learned from the simulations

Our analysis shows that in a business-as-usual world, Jordan faces escalating challenges:

- Socially: Diets become less healthy

- Economically: The country grows more dependent on food imports

- Environmentally: Fertilizer use and greenhouse gas emissions intensify

In contrast, the desired future—though ambitious—offers promising synergies:

- A healthier population

- Stronger domestic production and potential export growth

- Reduced vulnerability to climate shock

But not all looks bright in the desired future. Some trade-offs remain, especially environmental ones. Increasing the production of healthy foods could still lead to a rise in chemical fertilizer use. A so-called “efficiency paradox” may occur, where a highly productive agricultural sector creates incentives to increase production for export markets, potentially intensifying emissions. That’s why we advocate for holistic policy bundles that tackle health, trade, and sustainability together.

Building Trust and Enhancing the Usefulness of Foresight Modeling

By actively involving local stakeholders—from government agencies to civil society—we were able to strengthen both trust in the modeling process and its perceived relevance. Partnering with the right in-country actors significantly increases the likelihood that simulation results will inform real-world decision-making.

Key partnerships played a critical role in this effort. In addition to the indispensable contribution of in-country facilitators, we collaborated closely with the Food Security Council, NAJMAH (National Alliance Against Hunger and Malnutrition), and the Embassy of the Netherlands in Jordan. This inclusive, participatory approach laid the foundation for developing context-specific solutions, such as strategies to reduce food loss and waste tailored to Jordan’s unique food system challenges.

What Sparked Participant Interest

Workshop participants were particularly engaged during the presentation, raising thoughtful questions about both the participatory process and the technical foundations of the work. Many wanted to understand the core components that defined our participatory approach and the key assumptions behind the contrasting scenarios—especially the policy mechanisms underlying the “desired future” pathway.

There was also strong interest in how the modeling results could be translated into action, particularly how they might shape or influence policy development. Some attendees were curious about the data sources used for the Mediterranean diet, while others focused on the composition of stakeholders and whether that mix evolved over the project’s three-year duration.

By Bart de Steenhuijsen Piters

Foresight4Food is organizing its 5th Global Workshop in June titled “Foresight for Transformative Action in Food System”. To raise the tip of the curtain on this exciting event, we have asked Bart de Steenhuijsen Piters, Senior Scientist Food System at the Wageningen University and Research and Foresight4Food FoSTr programme facilitator, to share some of his thoughts and expectations. Here is what he has to say:

The myth of the “Global” food system

As we approach the 5th Global Foresight4Food Workshop in Jordan, I find myself reflecting on what it truly means to transform our food systems—and what role foresight can play in helping us get there.

Let me begin with a provocation: I believe the idea of a global food system is, in many ways, an illusion.

When we speak about the global food system, we often forget that it’s simply the aggregation of countless national and subnational systems. No one actor is responsible or able to govern it. The UN may think so, but that is an illusion. Instead, we have trillions of individuals, institutions, and businesses shaping the system every day. This diffused responsibility makes governance incredibly complex and leads to a kind of mystification, where the real (geo)political and economic dynamics at lower levels are ignored or misunderstood. Yet, all these food systems are connected for sure. Just look at the effect of the Trump administration and its tariff policies on food markets worldwide.

This is precisely where foresight can help—not by giving us a top-down blueprint but by helping us navigate complexity, anticipate challenges, and co-create transformative pathways.

What success looks like for the 5th Global Foresight4Food Workshop

For me, success for the 5th Foresight4Food Workshop doesn’t lie in just producing new scenarios. It lies in helping us figure out how to act in those scenarios.

I want us to co-develop a joint narrative around food system transformation. I want us to compare how different countries are exploring their options. Most importantly, I want us to dive into the real-world, practical question: how do we move from insight to impact? How do we build pathways for change that involve multiple actors, each taking responsibility? And how do we lead, especially when the pathway forward is contested and uncertain?

These are the questions I hope we will tackle together in Jordan.

Regional collaboration is crucial

One of the most powerful levers for transformation is regional cooperation. Not only does it allow us to share experiences and foresight approaches among practitioners, but it also aligns with the need for more localized, resilient food systems. This is especially critical in times when global markets are being challenged, multinational food companies continue to concentrate their power and food is more and more used for geopolitical purposes.

We need shorter, regional supply chains and production systems that are better tailored to local contexts. Regional platforms are essential for this. They help us valorise knowledge and foster innovation where it matters most—on the ground.

The leadership we need

Food system transformation demands leadership on many fronts.

We need business leaders who are willing to shift course—who can rethink business models that currently drive unsustainable outcomes and align their strategies with public goals like healthy diets and environmental sustainability.

But we also need leadership that can manage conflict and mediate between diverse interests. Sometimes, this means making bold policy decisions, even when powerful actors resist change. That kind of leadership isn’t easy—but it’s necessary.

A call for courage and collaboration

My hope for this workshop is that it becomes a space of real collaboration. A space where participants listen to each other, share not only their successes but also their failures, and resist the urge to simply push their own agendas.

We need the courage to explore the unknown together. To ask hard questions. To face the uncomfortable truths. Because only then can we unlock the systemic changes our societies so urgently need—and that, too often, are still moving too slowly or stalling altogether.

I look forward to learning with and from all of you in Jordan.