FAO’s new insightful scenarios for the future of food systems

By Bram Peters, Foresight4Food Global Facilitator

What drivers can trigger food systems transformation? How can we move beyond business as usual in the face of rising food insecurity, environmental degradation and economic instability? The good news is that we can shape food systems to be more resilient and sustainable. The challenge: trading off short-term benefits in search of longer-term outcomes. FAO developed four future scenarios that explore that explore these questions and how we can navigate such paths.

End of 2022, the United Nations Food and Agriculture Organisation (FAO) published the report ‘The Future of Food and Agriculture – Drivers and triggers for transformation’. The key triggers and drivers for transformation are identified based on a diverse and wide range of literature and expert knowledge and then applied to four scenarios to achieve the FAO goal of ‘Four Betters’: better production, better nutrition, better environment and better life. Trade-offs over time and the key use of policy triggers are at the centre of the report’s conclusions. This blog dives into these drivers and futures, and delves into the key implications of this report.

In Search of ‘Four Betters’

FAO strives for ‘Four Betters’: better production, better nutrition, better environment and better life. How to achieve such a vision, and how will this look in the future?Much depends on how drivers play out, how stakeholders tackle trade-offs, and how certain triggers are turned into policy options and implemented. The recent report makes clear that the historical development paths followed by high-income countries, drawing from hegemonic power, colonial wealth and unsustainable practices, are impossible for current low- and middle-income countries to follow. This requires a mindset shift regarding taking responsibility, sharing burdens and investing in a new type of focus on the long-term objective.

Difficult-to-navigate trade-offs and choices include:

- Short-term productivity gains against greater sustainability and reduced climate impact; “Better production starts from better, critical and informed consumption, but producing more with less will also be unavoidable”.

- Efficiency against inclusiveness; for instance, “technological innovations are part of the solution – provided new technologies and approaches are also accessible to the more vulnerable”.

- Short-term economic growth and well-being against greater long-term resilience and sustainability. In concrete terms, this means “selling the message that well-off people have to lose out economically in the short run, in order to reap environmental benefits and resilience for all in the medium and long term is counterintuitive in this short-termism era”.

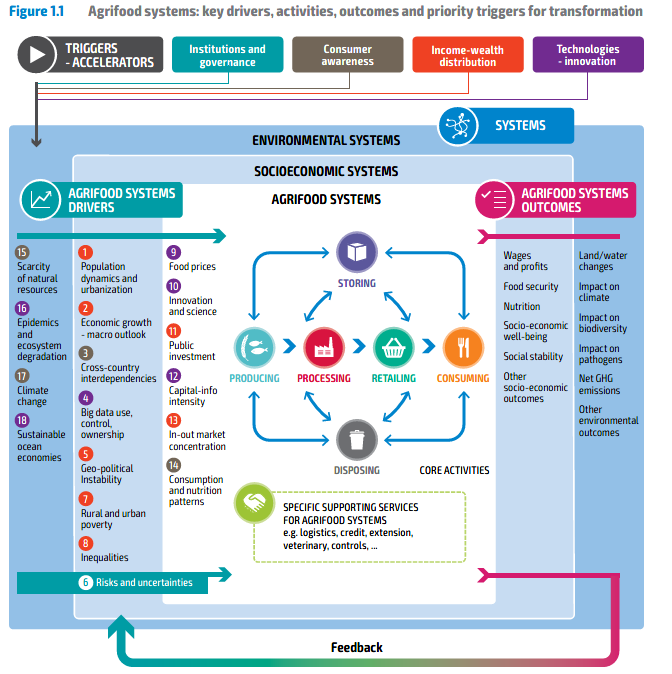

These are difficult but essential messages. The report highlights the importance of realising that food systems transformation is an inherently political and cultural process. Promising drivers and triggers for change are occurring globally, but must be harnessed and adapted. Let’s have a look at some of the drivers identified. Drivers are categorised as ‘overarching, systemic drivers’, which often include global, geopolitical and demographic elements, ‘drivers affecting food access and livelihoods’, and ‘drivers that affect food and agricultural production and distribution processes. Drivers within these categories affect agri-food, socioeconomic and environmental systems (Figure 1.1).

Captured in an agri-food system framework (partially based on previous work from Foresight4Food), some predominant drivers include scarcity of natural resources, epidemics and ecosystem degradation, cross-country interdependencies, inequalities, big data use and control, geopolitical instability, food prices, public investment and consumption and nutrition patterns. Cutting through these drivers are ‘risks and uncertainties’, as many drivers can turn into hazards, risks and cascading crises.

New Future Scenario Narratives

Radically divergent futures can emerge if the interactions of drivers, changes in individual and collective behaviour, the materialization of natural events, risks and uncertainties, and the influence of public strategies and policies play out differently. FAO developed four scenarios from the near future to the end of the century and explored the implications of each for food systems. The FAO ‘Four Betters’ were used to formulate four visions and narratives of the future. Using a ‘back-casting approach’ (where a number of aspirational visions are developed and it is then explored what future pathways could lead to these futures). The FAO team explored how each of these futures could be reached through combinations of key drivers, interconnections between agri-food, socioeconomic and environmental systems and ‘weak signals’ of possible futures.

By imagining alternative pathways and priority trigger points, the four scenarios are not defined as separate destinations to get to by moving along four different train tracks. Instead, each future

scenario could be reached at different points depending on the strategic policies and decisions implemented, the trade-offs in policymaking, and unless irreversible processes are triggered.

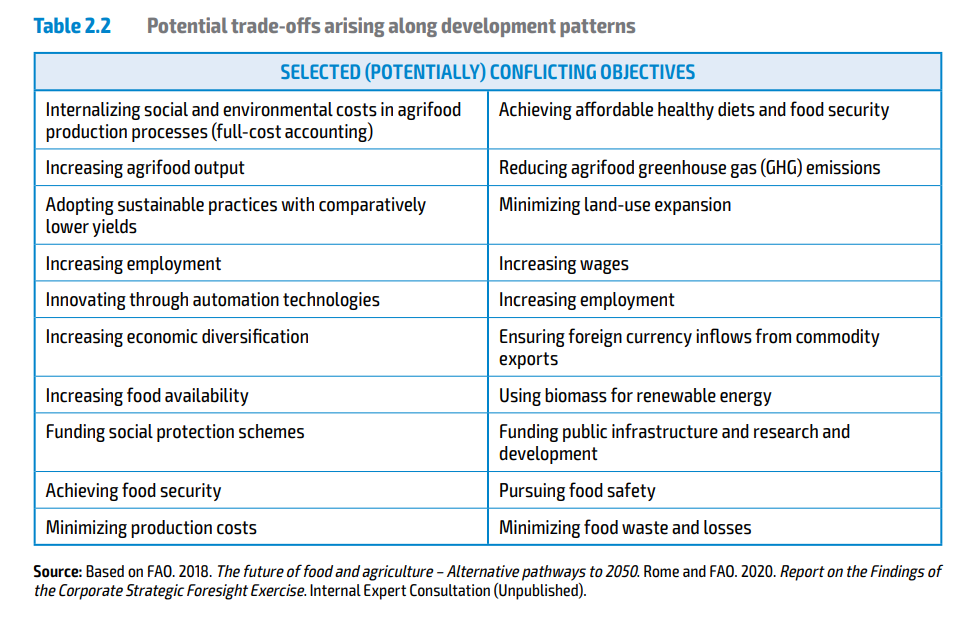

Trade-offs now and in the future will offer wicked dilemmas for decision-makers. Foresight thinking highlights that certain current decisions may lead to short term results but can increase medium and long-term uncertainty and, in the worst situations, foreclose certain long-term futures. See various conflicting policy objectives in Table 2.2.

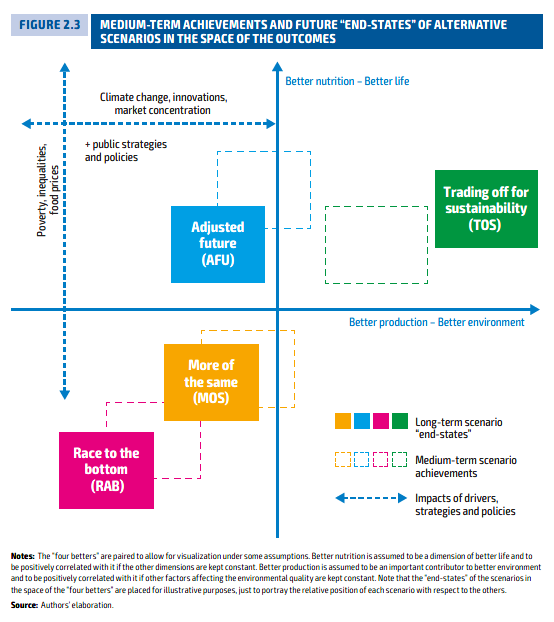

The four scenarios are visualised on a juxtaposition of 2 paired FAO ‘Betters’: ‘Better nutrition/Better life’; and ‘Better production/Better environment’. These betters were paired to enable visualisation and relative positioning of futures vis-à-vis each other in a matrix.

The four scenarios include:

1. More of the Same (MOS)

2. Adjusted Future (AFU)

3. Race to the Bottom (RAB)

4. Trading off for Sustainability (TOS)

More of the Same involves muddling through reactions to events and crises while doing just enough to avoid systemic collapse, which will lead to the degradation of agri-food systems’ sustainability and to poor living conditions for many, increasing the long-run likelihood of systemic failures. Adjusted Future entails that some moves towards sustainable agri-food systems will be triggered in an attempt to achieve Agenda 2030 goals. Some improvements in terms of well-being will be obtained, but the lack of overall sustainability and systemic resilience will hamper their maintenance in the long run.

Race to the Bottom is characterised by gravely ill-incentivized decisions that will lead to the collapse of substantial parts of socioeconomic, environmental and agri-food systems, with costly and almost irreversible consequences for a vast number of people and ecosystems. Trading off for Sustainability would mean that awareness, education, social commitment, sense of responsibility, participation and critical thinking will trigger new power relationships and shift the development paradigm in most countries. Short-term gross domestic product (GDP) growth will be traded off for the inclusiveness, resilience and sustainability of agri-food, socioeconomic and environmental systems.

Each scenario narrative explores how certain key domains could develop. What would geopolitics, economic growth, demographics, resources and climate, agriculture, and technology and investment in food systems look like in each future? How each key driver would materialise in each future is also illustrated. For instance, the driver ‘Innovation and Science’, in the MOS scenario, imagines that various agricultural technologies such as robotics, blockchain and AI were developed and were expected to support data-driven transformation but failed in the face of too much focus on means and not enough institutional and social innovation. In the AFU scenario, some investments in novel technologies helped improve productivity and resource use efficiency.

However, more systemic approaches such as agroecology and multi-cropping were not followed through and unequal investment across countries took place, meaning that real transformation was incomplete. In the RAB scenario, science was further used to ensure control of corporate entities or geopolitical allegiance, reinforcing inequalities and further exclusion of small-scale actors and leading to faster exhaustion of natural resources. Finally, in the TOS scenario, science and innovation are fully geared toward sustainable food systems and involve strong contributions from educated and aware civil societies using innovative decision-making processes. Greater awareness of consumers facilitated the trade-off of outputs with sustainability and supported the creation of a diverse and resilient agri-food system across communities.

Various assumptions always play a role in developing scenarios and their policy triggers. Compared to previous scenario exercises, a key assumption, due to updated data models and prognoses, is that the collapse of substantial parts of agri-food, socioeconomic and environmental systems is almost certain(!). A second important assumption in the TOS and RAB scenarios is that ‘globally emerging well-educated, informed, critical, increasingly aware and non-manipulable civil societies’ are a crucial factor that either can enable or prevent those futures from being realised. Another assumption is that governance of markets is important to address inequalities. This is contrary to scenarios developed by the World Economic Forum, where the assumption was that if markets are connected and economic growth is fast, inequalities will also decrease.

So, what does it mean to work with these futures?

Concluding most directly: the picture is not reassuring, but something can be done if with urgency. SDG achievement is off track, finding ‘win-win’ solutions is difficult if not impossible, and MOS and RAB scenarios must be avoided with great urgency as they could very well become reality. However, the implications of the scenarios and the complexity of food systems also mean that other lessons require deeper reflection. Two elements are essential to underline: the interconnectedness of systems and our abilities to boost transformative change.

The interconnectedness of systems means that negative trajectories and global challenges can cascade into even bigger crises. Solutions cannot emerge easily due to entangled problems within agri-food, socioeconomic and environmental systems. Climate change, shock resilience, sustainable resource use, poverty and ending hunger are at the top of overarching challenges.

Agency grants us the means to set a new path, but it may be challenging to implement change under the influence of drivers and opposing power and interests. As such, being on the path toward MOS or RAB does not mean that we cannot set in a new direction. We must utilize ‘priority triggers of change’ or boosters of transformative processes to move away from business as usual. The report identifies four key policy triggers: institutions and governance; consumer awareness; income and wealth distribution; and innovative technologies and approaches.

Following a systemic logic, changes made through these triggers within the agri-food system should also impact socioeconomic and environmental systems. Activation or deactivation of these triggers (especially regarding which stakeholders gain the power to influence the manner of their activation) will highly influence the realisation of certain scenarios. For instance, better institution and governance mechanisms will influence on a range of key drivers and domains, such as better institution and governance mechanisms will influence on a range of key drivers and domains, such as governance of new technologies, migration, market power and intergenerational equity.

The report concludes with the words of Antonio Gramsci, Italian philosopher and radical journalist. “My mind is pessimistic, but my will is optimistic. Whatever the situation, I imagine the worst that could happen in order to summon up all my reserves and will power to overcome every obstacle”: words to be taken to heart. Acceptance of long-term perspectives by citizens and their governments is crucial for transformative action to start now. We must ‘outsmart’ political-economic constraints and enlarge agency space.

As Foresight4Food, we are committed to promoting and enhancing foresight approaches to strategically prepare for different food systems outlooks, by learning from the past but especially looking forward to explore.