By Bhawana Gupta and Monika Zurek

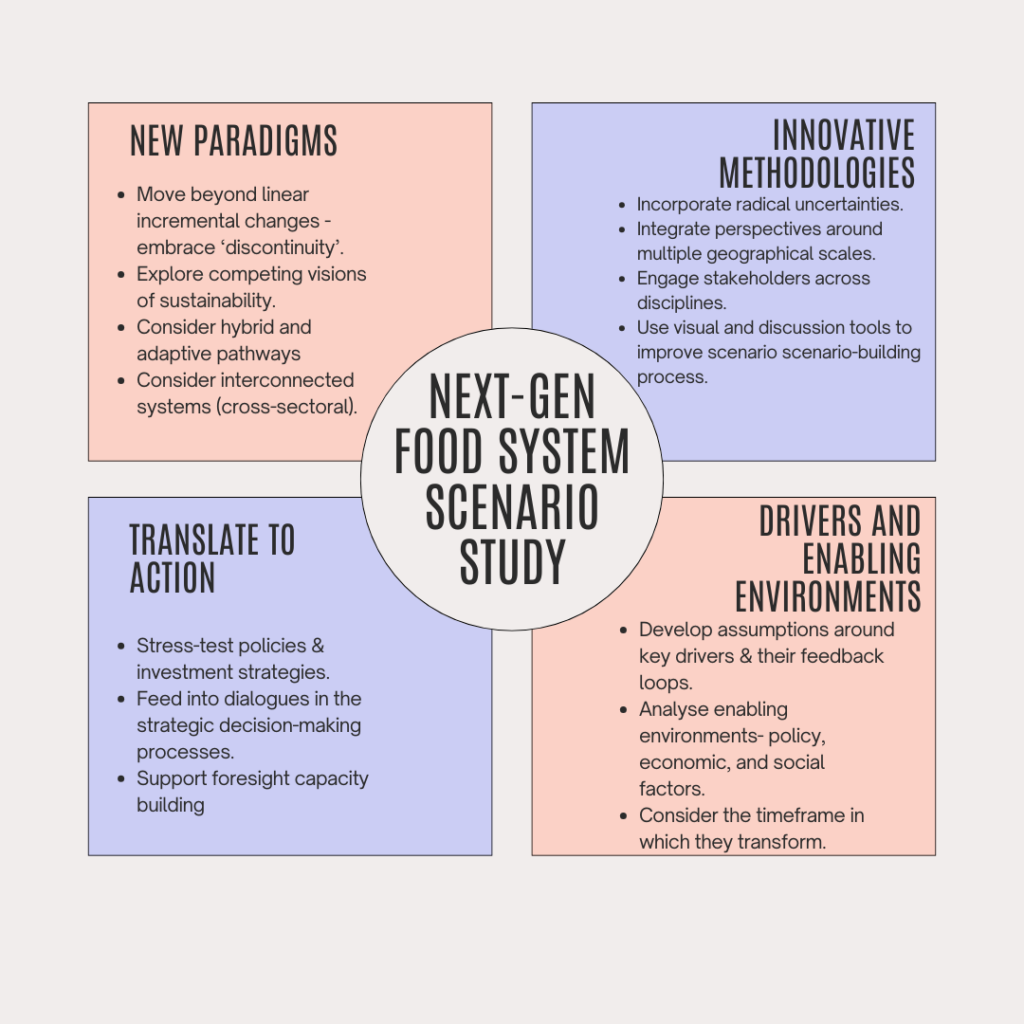

What if the future of our food system looks nothing like what we’ve imagined so far? Our recent report “Food systems of the future” examines how foresight studies are shaping our view of what’s to come. It reveals the urgent need for a new wave of forward-thinking work that dares to imagine fundamentally different food system configurations. Next-generation food system scenarios must embrace a new change paradigm, innovative methodologies, and a clear pathway to incentivise action through a deeper understanding of future drivers and enabling environments.

Why do we need another global-level scenario study?

We live in what many call the acceleration phase of the Anthropocene, an era defined by rapid and unpredictable change. For years, scholars and practitioners across disciplines worked to unravel the complexities of our global food system, using scenarios as vital tools to explore how different forces shape its future. But it’s crucial to remember that these scenarios are not only built on data; our assumptions, beliefs also shape them, and our constantly evolving grasp of the drivers of change[i].

The evolution of food system scenarios reflects this shift. Early models mostly focused on projecting food production and demand based on population growth. Over time, their scope broadened to encompass factors like resource availability, climate change, policy shifts, and socio-economic dynamics. Yet, the turbulent events of the past five years—think of the global pandemic, geopolitical tension, and unexpected supply chain disruption—have shown us that even the most sophisticated scenarios failed to capture certain uncertainties.

Grappling with the multifaceted complexities of the future is undoubtedly a wicked problem. But by continually refining our foresight techniques, we can better prepare for future shocks and proactively design alternative pathways. Let’s explore the critical building blocks for this next generation of global food system scenarios.

1. New paradigms

In Donella Meadows’ view, a paradigm is a shared set of beliefs, values, and assumptions that underlie a system. This core mindset dictates the system’s goals, structures, and operational rules. It follows that a paradigm shift is one of the most powerful drivers of lasting change within a system. For our discussion, there are three aspects that should be considered:

- Discontinuity: Past scenario studies often urged the inclusion of a surprise element or discontinuity[ii] (read box 1 for definition). However, these discontinuities were considered weak in almost all scenarios, especially quantified ones. Instead, scenario studies emphasised continuous incremental changes in the system. Going forward, our scenarios must move beyond a smooth and predictable evolution to explicitly explore non-linear changes, tipping points, and abrupt shifts.

BOX- 1

The term discontinuity is used variously in scenario literature, broadly signifying a sharp departure from past trends caused by high-impact developments, phenomena, and events. The significance of a discontinuity depends on its character, magnitude, speed, and ripple effects, and whether it has been anticipated and ameliorated. Here, a discontinuity refers to a significant shift of social-ecological structure and dynamics, rather than a transient perturbation after which the system reverts to its original trajectory. Related terms are surprises, bifurcation, critical transition, tipping points, tipping elements, wild cards, and black swan events. More recently, the phrase game changers has been introduced for shifts in how society is organized through understandings, values, institutions, and social relationships.

- Mental models: Since the IPCC’s ‘Shared Socio-economic Pathways’, most global scenario studies have relied on a mental model that assumes four broad pathways:

- A sustainable pathway characterised by progressive policy and technological adoption.

- A business-as-usual pathway, projecting a continuation of current trends.

- A collapse or environmental destruction pathway, depicting worst-case outcomes.

- A divided world pathway, where inequalities worsen and cause socioeconomic distress.

While seemingly intuitive the widespread use of this mental model is influenced by cultural biases, cognitive processes[iii], and the culture of scientific reticence[iv] (read box 2 for more). These factors can lead to the design of scenarios that are overly simple, feel intuitively right, and align with common ways of thinking about the future: an optimistic view, a middle ground, and a pessimistic view. We must challenge this reliance on simplistic archetypes and embrace more nuanced and multi-dimensional perspectives in our scenario development.

BOX- 2

Anchoring bias: We tend to rely too heavily on initial information, making it difficult to envision radically different futures.

Confirmation bias: We seek out information that confirms our existing beliefs, reinforcing the status quo.

Incrementalism: We assume change will be gradual and predictable, neglecting the potential for sudden, non-linear shifts.

Lack of interdisciplinary input: Many scenario studies are limited by the perspectives of a narrow range of experts, missing crucial insights from other fields like sociology, ecology, and complexity science.

- Cross-sectoral linkages: Too often, scenario studies operate in isolation, focussing on a single system like food. They fail to incorporate the strong interdependencies with other critical systems such as energy, water, or social systems. This approach can create a lack of understanding of the potential for cascading system failures, or conversely, unexpected positive feedback loops. Future scenarios must explicitly model these intricate interconnections, exploring how changes in one sector can trigger ripple effects across others.

2. Innovative methodologies

Advancing food system scenarios requires leveraging innovative methodologies, for example:

- Multi-scale analysis: Most past food system scenario studies focused on processes at specific geographic scales. Yet food systems operate across a spectrum, from individual households to global markets, with numerous complex inter-dependencies. These dynamics need to be captured in the future studies. The methodology for linking scenarios at different scales was explored by Zurek et al[v]. By integrating local, regional, and global food system dynamics, we gain a more holistic understanding of potential futures.

- Radical scenario development: The scenarios developed in the last decade have often underplayed outlying, surprise, or disaster events[vi]. Yet the inclusion of diverse and radical uncertainties can advance the quality and utility of scenarios[vii]. The development of radical scenarios combines established scenarios with group discussion techniques, as discussed in Talwar et al.[viii]. We need to better embrace wild cards and black swans as integral parts of scenario development, exploring how low-probability, high-impact events can reshape the future.

- Multi-disciplinary expert involvement: Food systems are inherently complex and interconnected, necessitating the involvement of actors across multiple sectors (e.g., agriculture, trade, health, and environment) and governance levels (from local to global). Innovative participatory methodologies such as Transdisciplinary Foresight Labs[ix] and Causal Layered Analysis (CLA)[x] can unpack issues on various levels and uncover underlying assumptions around litany, systemic causes, worldviews, and myths that shape expert opinions. Together, these methodologies support more holistic, inclusive, and imaginative scenario processes.

3. Drivers and enabling environments

Today’s scenarios commonly describe assumptions around the drivers of change (e.g. technological shifts, demand patterns, and trade dynamics). Next-generation studies must go further and reflect on the enabling environments that shape the dynamics of future food system drivers and the timeframe within which the change unfolds. This includes[xi]:

- Policy and governance: How do regulations, institutional capacity, and international agreements shape food system operations?

- Economic and financial structures: How do investment patterns, trade dynamics, and economic inequality influence food access and production?

- Social and cultural context: How do changing consumer preferences, social equity, and cultural norms drive food demand and system practices?

- Technological and infrastructural frameworks: How does digital connectivity, research and development (R&D), and infrastructure development enable or constrain food system innovation?

- Environmental governance: How do policies and practices regarding resource management and climate change impact food production sustainability?

4. Translate to action

Developing next-generation scenarios is not just an academic exercise. To be truly impactful, these studies must bridge the gap between foresight and implementation, ensuring that scenario narratives translate into policy and strategic actions. This involves:

- Using real-world stress tests: Running policies and investment strategies against multiple scenario conditions to assess their resilience.

- Embedding scenario thinking: Integrating foresight and scenario planning directly into decision-making processes at national and global levels. (Read about institutionalising foresight in decision-making in another blog).

- Engaging non-traditional stakeholders: Involving a broader range of voices, including grassroots organizations, indigenous groups, and regenerative farmers, to develop a shared language around food systems and future pathways.

Conclusion

Essentially, the prevailing paradigm in many current scenario studies inadvertently restricts our imagination and limits our collective ability to envision and prepare for truly transformative change. It creates an illusion of control in a world that is far more contingent and unpredictable. The necessary shift towards scenario studies that adequately reflect paradigm shifts is a complex but crucial endeavour, requiring a fundamental rethinking of how we construct and interpret future possibilities.

The food system of tomorrow will not be shaped by predictions, but by our collective capacity to anticipate, adapt, and transform. Advancing next-generation global food system scenarios requires bold thinking, cross-sector collaboration, and an openness to radical possibilities. The question remains: are we ready to embrace this challenge?

[i] Cork, S., Alexandra, C., Alvarez-Romero, J.G., Bennett, E.M., Berbés-Blázquez, M., Bohensky, E., Bok, B., Costanza, R., Hashimoto, S., Hill, R. and Inayatullah, S., 2023. Exploring alternative futures in the Anthropocene. Annual Review of Environment and Resources, 48(1), pp.25-54.

[ii] Rothman, D.S., Raskin, P., Kok, K., Robinson, J., Jäger, J., Hughes, B. and Sutton, P.C., 2023. Global Discontinuity: Time for a Paradigm Shift in Global Scenario Analysis. Sustainability, 15(17), p.12950.

[iii] Cork, S., Alexandra, C., Alvarez-Romero, J.G., Bennett, E.M., Berbés-Blázquez, M., Bohensky, E., Bok, B., Costanza, R., Hashimoto, S., Hill, R. and Inayatullah, S., 2023. Exploring alternative futures in the Anthropocene. Annual Review of Environment and Resources, 48(1), pp.25-54.

[iv] Rothman, D.S., Raskin, P., Kok, K., Robinson, J., Jäger, J., Hughes, B. and Sutton, P.C., 2023. Global Discontinuity: Time for a Paradigm Shift in Global Scenario Analysis. Sustainability, 15(17), p.12950.

[v] Zurek, M.B. and Henrichs, T., 2007. Linking scenarios across geographical scales in international environmental assessments. Technological forecasting and social change, 74(8), pp.1282-1295.

[vi] Gupta, B., Zurek, M.B., Woodhill, J. and Ingram, J. 2025 submitted for publication to Frontiers in Sustainable food systems

[vii] Gordon, D., 2021. Radical Uncertainty: Decision-Making Beyond the Numbers. Quarterly Journal of Austrian Economics, 24(1), pp.206-210.

[viii] https://jfsdigital.org/2019/06/15/the-future-of-energy-reinvented-case-study-of-the-radical-scenario-development-approach/

[ix] Pólvora, A. and Nascimento, S., 2021. Foresight and design fictions meet at a policy lab: An experimentation approach in public sector innovation. Futures, 128, p.102709.

[x] UNDP (2022). UNDP RBAP: Foresight Playbook. New York, New York.

[xi] Gupta, B., Zurek, M., Woodhill, J., Ingram, J. (January, 2025). Food Systems of the Future: A synthesis of food system drivers and recent scenario studies. Foresight4Food. Oxford, United Kingdom.

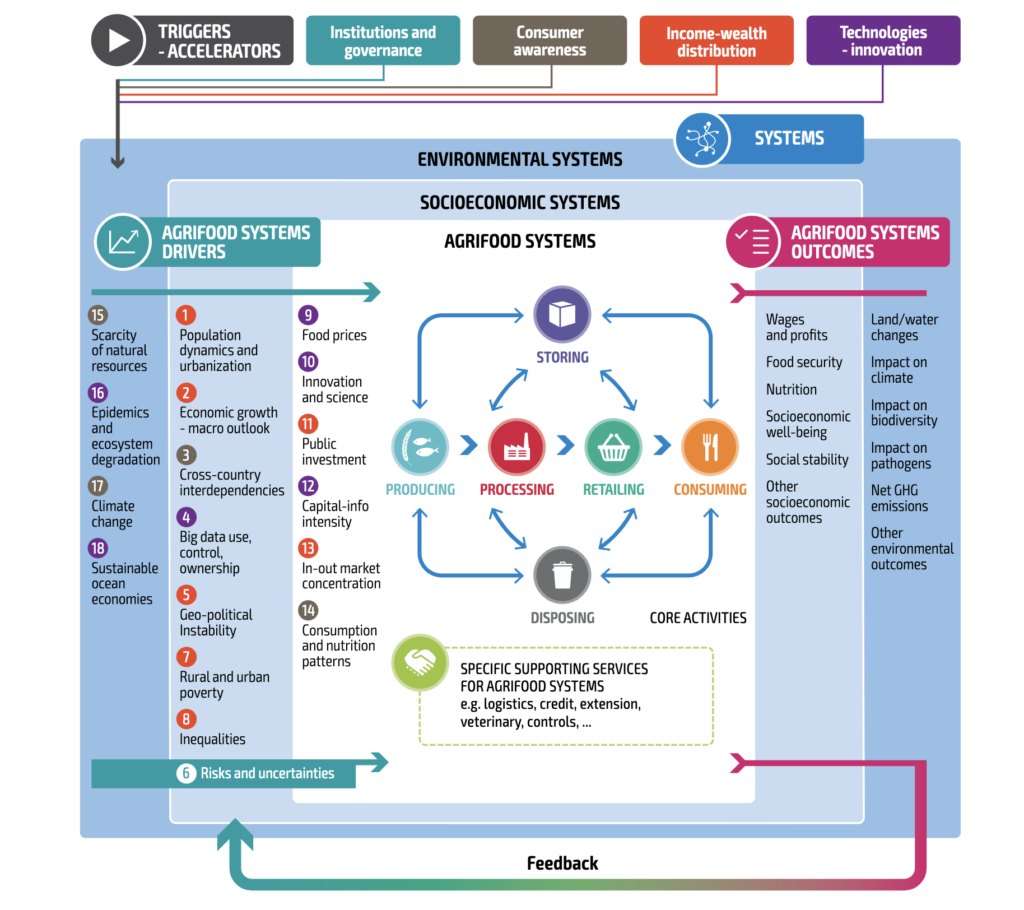

The global food system needs to be transformed. It needs to deliver better health and improved livelihoods while protecting the environment and minimizing negative social impacts.

However, there are many interconnected factors playing a role. Food Systems are complex adaptive systems which require a deep analysis of their various driving forces and dynamics. They are shaped by a multitude of interconnected factors or drivers, some well-defined, others with a lot of uncertainties with them. A recent study by Forsight4Food identified the most critical drivers of the global food system as described by a set of 19 recent foresight reports. It was not easy to define and categorize these very drivers, and we will also discuss these challenges in this blog.

The Entangled Web of Drivers

Many studies, from the 2003 Millennium Assessment report to FAO 2022 have defined what is a ‘driver’. But the challenge is the lack of a universally agreed-upon definition for a driver. This means that categorizing these drivers is problematic. For instance, they can be classified based on their relationship with other drivers (direct or indirect), external factors (like PESTLE analysis- Political, Economic, Sociological, Technological, Legal and Environmental), or the extent of our knowledge about them (known knowns or unknown unknown).

What makes it even more intricate is that, due to the systemic nature of the food system, its nutrition, environmental condition, and economic development outcomes feedback indirectly becomes driver themselves. This creates feedback loops that complicate pinpointing which drivers are truly direct and which are indirect. Ultimately, it depends on the specific part of the system you’re focusing on. This is nicely depicted in the FAO’s food system diagram, however, it does not show the interconnections between different factors which is what needs careful consideration.

Source: FAO 2022

Here’s another layer of complexity: There are “known knowns” drivers like climate change and population growth and many models have been developed to understand the future trend. Then there are drivers such as government interventions (trade policies and subsidies) which is undoubtedly an important driver, but predicting the future impact of specific interventions is challenging. Similarly, we understand that diets are shifting towards more protein, but whether this trend holds true depends on the specific scenario we’re considering. These are “known unknowns” – we know they exist, but their future impact is a mystery. But the complexity is even deeper: “unknown unknowns”. Take the influence of social media on food choices. This is a relatively new area of study, and its full impact on the food system remains unclear. There can be overlaps in any type of categorisation system. Therefore, it is important to involve experts at this stage.

Identifying the Critical Few

The next hurdle is identifying “critical drivers” – those with the most significant potential to impact the food system. These drivers can influence various stages through established historical trends or emerging uncertainties. A key challenge lies in determining their relative importance across diverse contexts, often depending on stakeholder perspectives. For instance, immigration policies can have a significant impact on agricultural workforces in some regions. Incorporating stakeholder consultations is crucial to prioritize the most impactful drivers in these specific contexts.

Keeping the Conversation Open

It’s vital to remember that the impacts of drivers manifest differently across various socio-economic settings and among different food systems stakeholders. Highlighting the context in which a driver is critical helps us develop more targeted solutions.

We must also acknowledge that new or emerging drivers with unclear trends can also have profound impacts. For example, as mentioned earlier, the role of social media in influencing food choices is a relatively new area of study.

Therefore, the conversation around identifying critical drivers needs to be open to periodic updates. As we uncover new information and witness the emergence of new drivers, we can refine our understanding of the food system and adapt our strategies accordingly.

Future Trends and Projections

The future trajectory of these drivers is influenced by various factors, both internal and external to the system. Climate change, consumer behaviour, and technological advancements all play a role in shaping the path ahead. These complexities of cross-impacts create uncertainties about the future, often interpreted through different assumptions in various projections.

Many reports from IPCC, FAO and UNDP present some of the trends and projected trends around food system drivers. But these vary due to the underlying assumptions. Moreover, deciphering these projections can be challenging due to two key factors: 1) varying timescales and 2) diverse representations of what a sustainable food system actually looks like. However, by delving deeper into these assumptions and comparing them, we can gain a more comprehensive understanding of the possible futures that lie ahead.

What we found…

The review of recent studies on food system drivers revealed a mix of established and emerging influences. We categorised drivers using the known-knowns and known-unknowns classification. Long-standing factors like demographic changes, climate issues, technological innovation, resource efficiency, socio-economic inequalities, government interventions, health considerations and level of connectivity continue to shape food systems, while new drivers such as the rise of e-commerce post-COVID-19, concerns about power imbalances in food value chains, labelling and packaging, data ownership issues, the role of indigenous knowledge, labour migration policies and perceptions around vegan and vegetarian diets are gaining importance. The relevance of these drivers varies based on stakeholder perceptions, indicating the diverse issues decision-makers must consider for effective management and adaptation.

The review also noted varying levels of uncertainty associated with these drivers. Established drivers, such as demographic trends, have narrower uncertainty ranges due to extensive research, leading to more consistent projections. However, differences in time frames, methods, and assumptions among studies complicate direct comparisons of quantitative trends. Emerging drivers, like government interventions and social media’s influence on consumer behaviour, exhibit broader uncertainty ranges and diverse trend directions, making them particularly significant for developing future scenarios. Our upcoming report will discuss these critical points in detail.

Conclusion

Transforming global food systems to deliver better outcomes is a complex and urgent challenge. Understanding the critical drivers shaping these systems, both well-known and emerging, is essential for creating the societal understanding and political will needed for meaningful change. Just as a map evolves with new discoveries, our understanding of these critical drivers needs constant refinement. Through ongoing research, collaboration, and open communication, we can navigate the complexities of the food system and support targeted solutions towards a more sustainable food system.