By Jim Woodhill and Bram Peters

We’re excited to launch our new guide: “Using Foresight for Food Systems Transformation – A Guide for Policymakers, Practitioners, and Researchers.” Developed collaboratively by the UN Food Systems Coordination Hub and Foresight4Food, this guide is being released today to coincide with the UN Food Systems Summit +4 Stocktake (UNFSS+4), taking place in Addis Ababa, Ethiopia, from July 27 to 29.

Why This Guide Matters

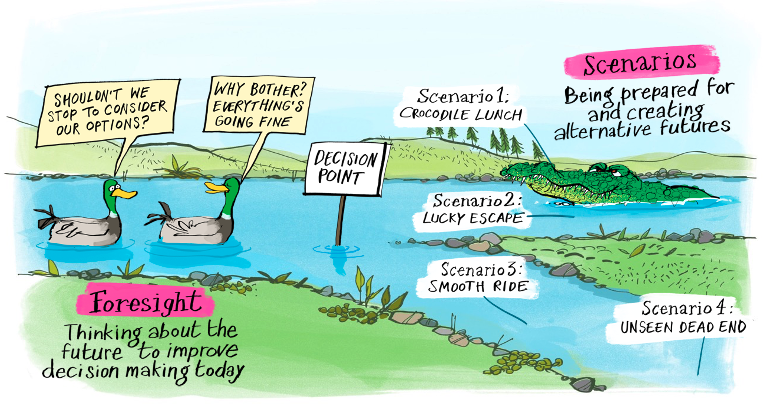

Transforming food systems to ensure better health, greater equity, and environmental resilience demands future thinking. We must collectively envision how our food systems can evolve—and confront the risks of “business as usual.” Anticipating future shocks and stresses can help drive proactive policy, investment, and innovation before crises hit.

This guide is a hands-on resource for applying foresight and scenario analysis at national and local levels to accelerate food systems transformation. It demystifies the basics of foresight, lays out practical steps for launching a foresight process, and offers real-world examples and curated resources.

What You’ll Find in the Guide

- Clear explanations of foresight and scenario analysis methods

- Step-by-step guidance for facilitating participatory foresight processes

- Insights and tools drawn from the global Foresight4Food network

- Case examples illustrating how foresight is being used in diverse contexts

At the heart of this approach is bringing together diverse stakeholders—from farmers and consumers to policymakers and private sector actors—to build shared understanding, trust, and momentum for collective action.

Part of a Broader Set of Resources

This new guide complements the Foresight4Food “Foresight for Food Systems Change Process Guide & Toolkit”, which dives deeper into participatory tools and techniques for systems mapping and scenario building.

It also aligns with new resources like FAO’s “Transforming Food and Agriculture through a Systems Approach”, which supports systems thinking for transformation. In parallel, Alliance Biodiversity and CIAT are highlighting the importance of subnational stakeholder engagement as a critical entry point for change.

A Call to Action

Transforming food systems will require significant investment—but more importantly, it needs broad-based commitment. Consumers, producers, businesses, and political leaders must be aligned on the necessary changes and the trade-offs involved. That means shifting mindsets, creating political will, forging new alliances, and rebalancing power.

As we move beyond the UNFSS+4, we need renewed focus on investing in high-quality, inclusive stakeholder processes. The foresight approach outlined in our new guide offers a powerful pathway to doing just that.

By Jim Woodhill, Lead Foresight4Food Initiative

Last week, I had the wonderful opportunity to support a regional training workshop on foresight for systems change in Nepal, in collaboration with the International Centre for Integrated Mountain Development (ICIMOD).

The workshop brought together a group of 35 development practitioners from across the Hindu Kush Himalaya region, including participants from Nepal, Bangladesh, Bhutan, India, and Pakistan. The focus was on how to use foresight to help tackle the big regional issues of climate adaptation, creating diversified and resilient livelihoods in mountain areas, migration, and disaster preparedness.

ICIMOD invited Foresight4Food to collaborate in facilitating the training, using Foresight4Food’s Framework of foresight for systems change following the organization’s participation in a similar leaders capacity development workshop held in Africa in 2023 (see report and video here) and Foresight4Food’s 4th Global Meeting in Bangladesh.

The Nepal event was a good chance to build on Foresight4Food’s capacity development experience in Kenya, Jordan, Bangladesh, and Uganda. These are focus countries for the Foresight for Food Systems Transformation (FoSTr) programme, supported by the International Fund for Agricultural Development with funding from the Dutch Government.

While food issues were only part of the focus of the workshop, the issues raised during the week yet again highlighted that the way food is consumed and produced is central to all development issues. Migration, climate adaptation, equitable livelihoods and managing disasters are all interconnected with agrifood systems.

What was covered in the training workshop?

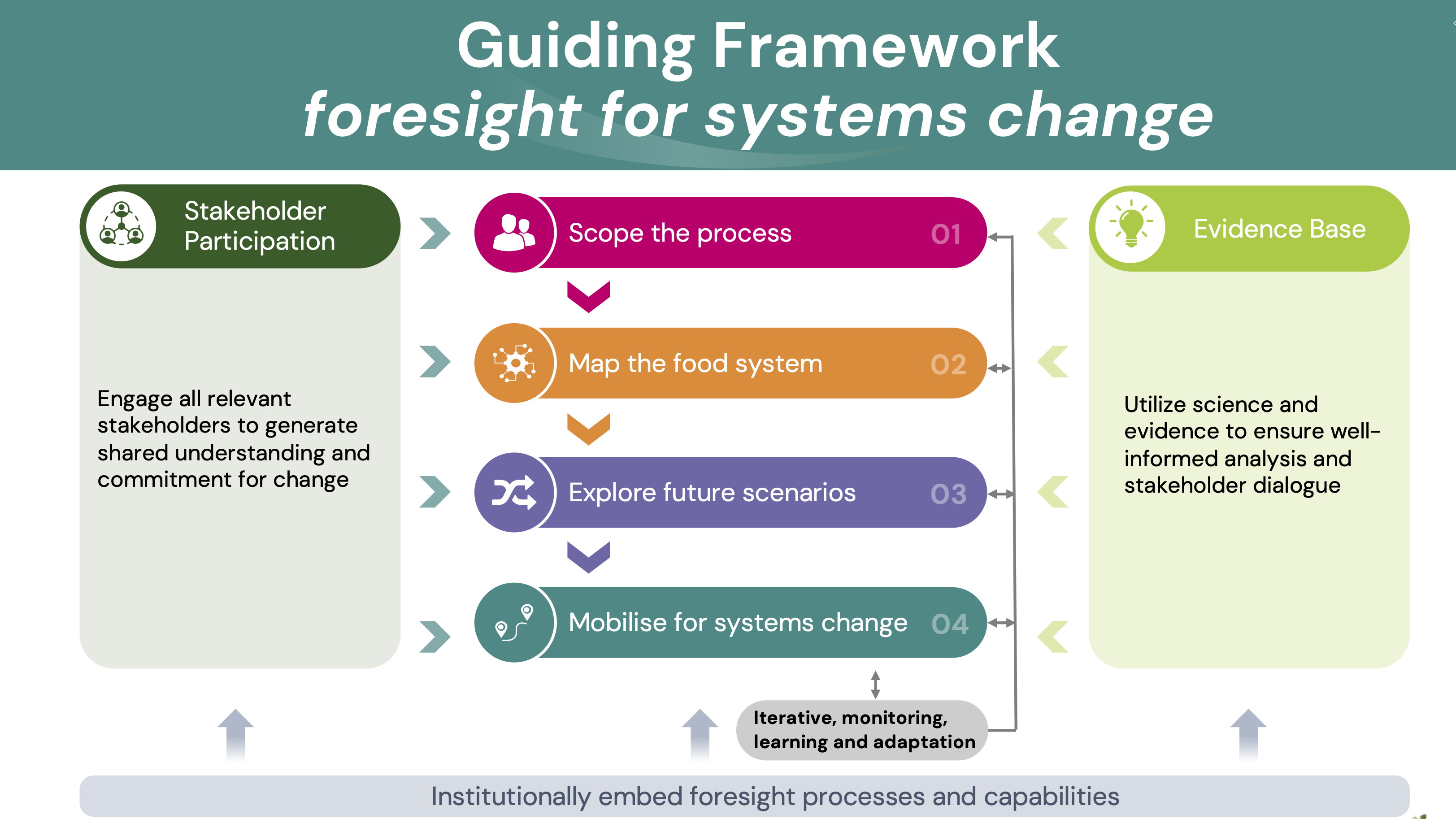

During the week, the participants worked through the four main phases of the Foresight4Food Framework:

- Scoping the process

- Mapping the system

- Exploring future scenarios

- Mobilising for systems change

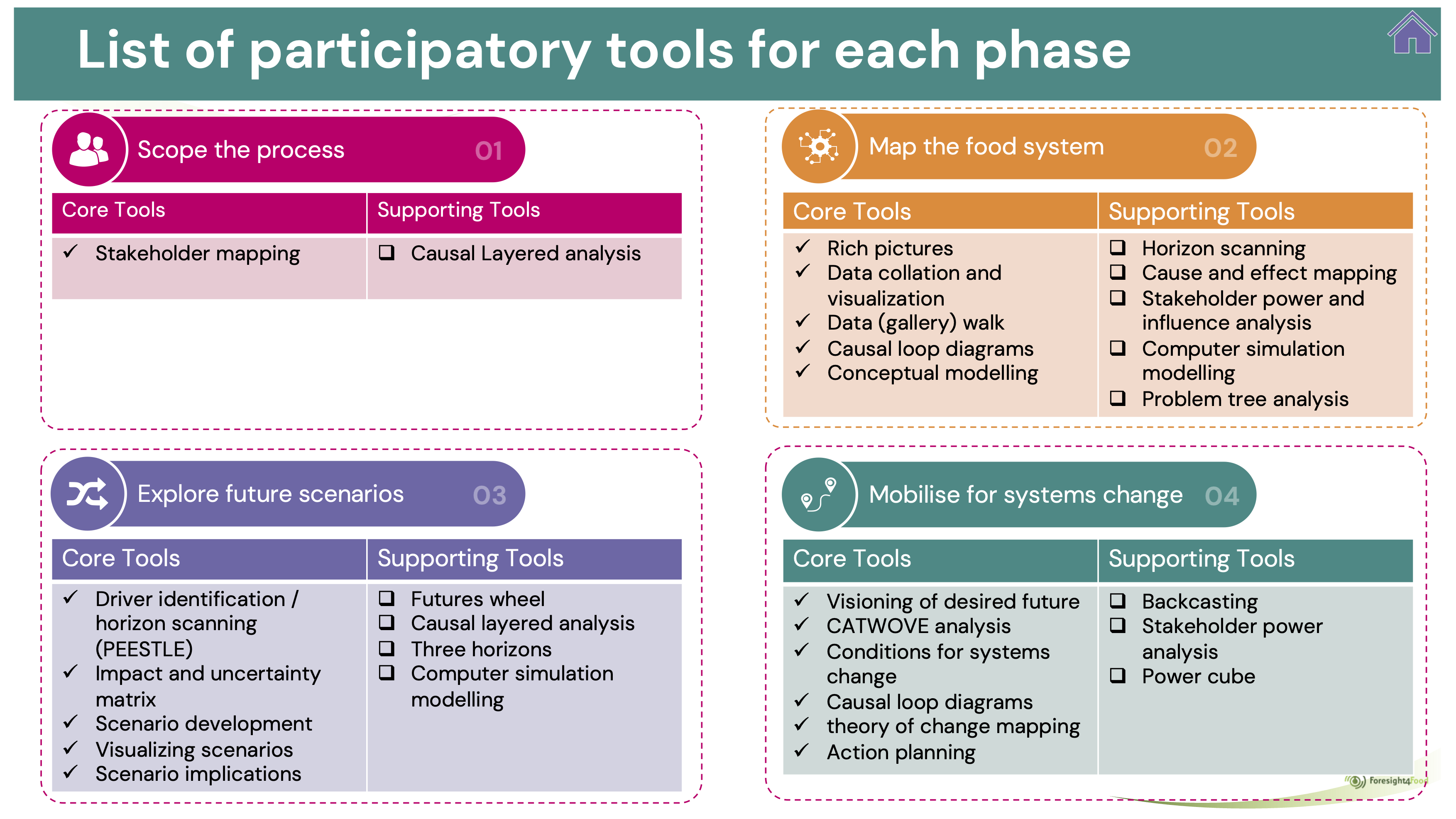

For each phase, participants were introduced to background concepts and theory, and relevant participatory foresight and systems thinking tools. Rich pictures, drawn by participants to illustrate the whole system, is always a favourite. Other tools we worked with included horizon scanning of future trends and uncertainties (guided by the PEESTLE acronym), data exploration, causal loop diagrams, scenario development, visioning, back casting and conceptual modelling of systems.

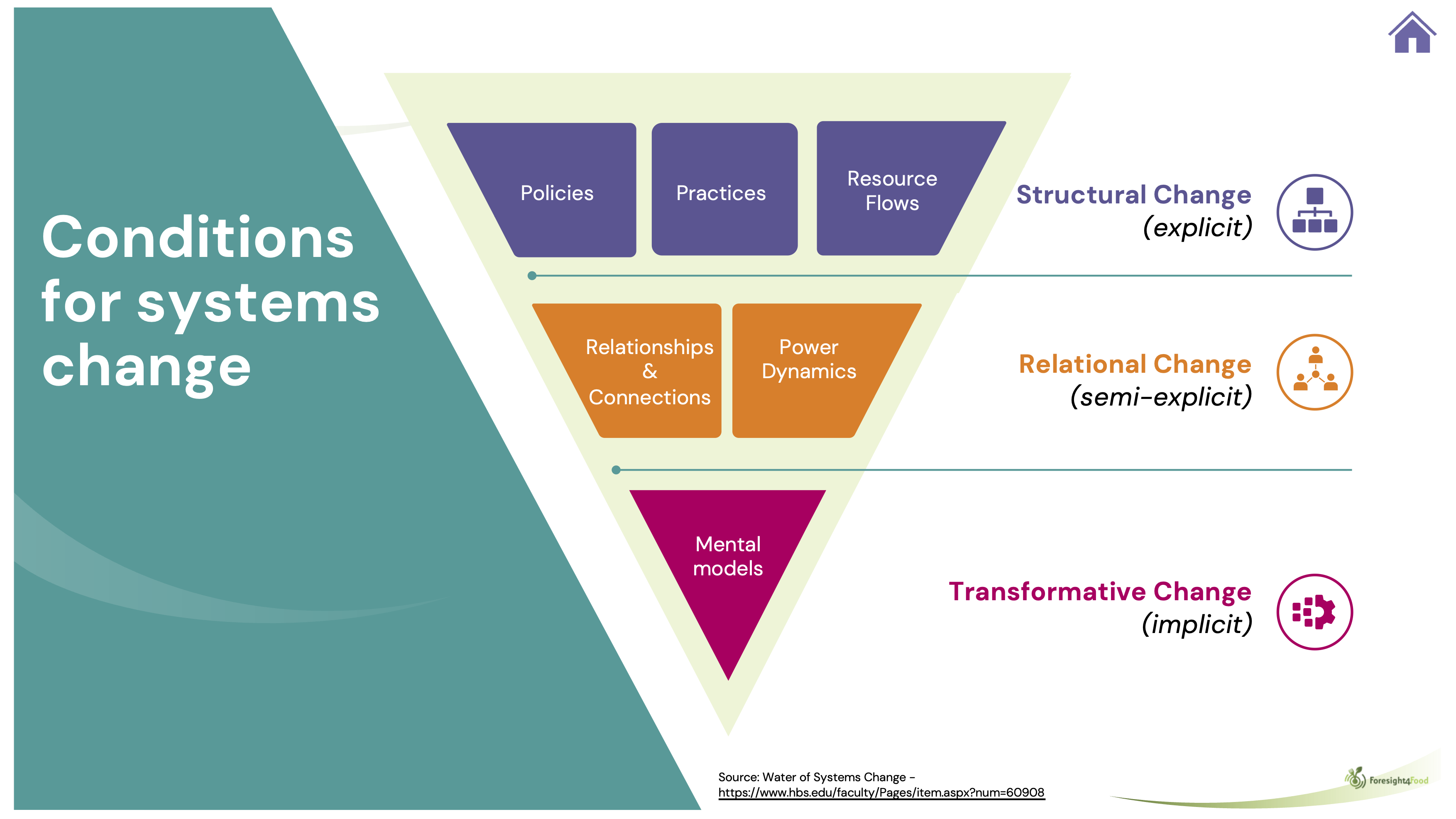

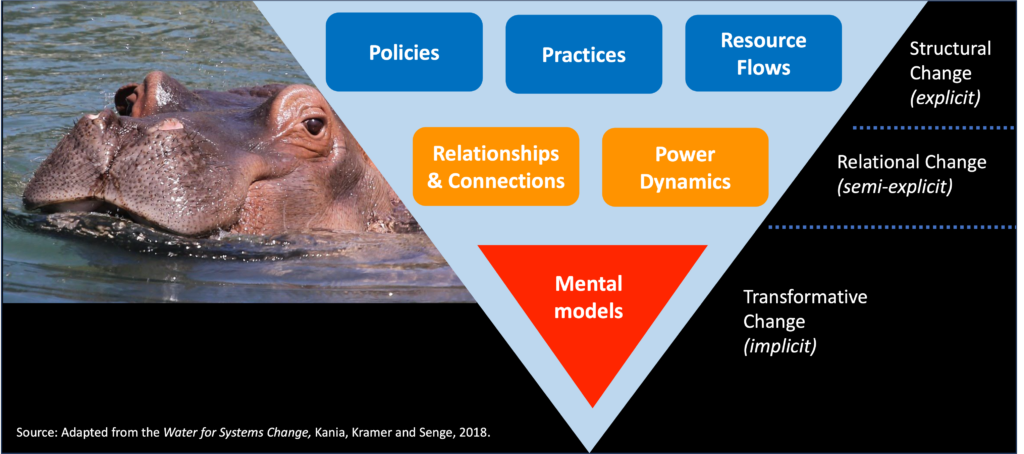

We discussed how change happens in complex adaptive (human) systems. The systems change “triangle” helped thinking about the role that mindsets and different forms of social and political power play in enabling or constraining change. The importance of bringing a gender equity and social inclusion (GESI) perspective to foresight was highlighted.

Participants applied their learning directly to the issues of climate adaptation, pastoralism, migration, and disaster preparedness.

The need for foresight

The global polycrisis is having a big impact on the Himalayas. The confluence of climate change, conflict, disease risk, inequality, biodiversity loss and geopolitical instability are bringing high levels of uncertainty and turbulence for citizens, businesses and governments across the region. For example, the melting of glaciers and the impact of extreme rainfall has profound implications for life in the mountains as well as for the billions of people who depend on the river systems that flow out of the Himalayas.

The Himalayas sit in the middle of a region with significant political tensions and shifting powers, which has major implications for the collaborative governance needed to effectively respond.

Foresight for systems change can help communities, organisations and governments better anticipate future risks and reimagine the future, so as to be more adaptive and resilient.

Thinking ‘out of the box’ – Foresight or “shortsight”?

Challenging discussions emerged during the week about how to ensure that foresight processes don’t just end up with the same old stuff – “old wine in new bottles”. To avoid this, we explored the need for “out of the box” thinking. This means looking for weak signals that might indicate a coming disruption, challenging assumptions about the future, bringing different perspectives to the table, using creative techniques to imagine radically different futures, and using the insights of “futurists”. A comprehensive horizon scanning process that explores mega-trends, trends, weak signals, critical uncertainties and wildcards helps to ensure foresight rather than “shortsight”.

Beyond tokenistic stakeholder participation

Across the Himalayas, it is local communities, local government and local businesses who must cope with the direct impact of floods, extreme heat, price fluctuations or disease outbreaks. Time and again participants returned to the importance of engaging local stakeholders to understand the challenges, and to generate pathways for greater resilience.

The discussion led to a shared understanding that this kind of participation from stakeholders requires genuine and open dialogue, made possible by using participatory workshop tools and techniques. However, all too often stakeholder engagement processes, when they do happen, fall back to formalised meeting structures, with speeches and presentations by “important” people, with little or no use of the sort of participatory analysis and dialogues tools participants engaged in during the training week. Advocating for effective, participatory and transformative stakeholder engagement processes is an obvious role for ICIMOD.

Institutional barriers to foresight and systemic practice

At the end of the week participants explored how to use foresight and systems thinking and practice in their own working context. Then some of the realities hit home.

Funders and donors often still force very linear, short-term and inflexible modes of programme design and management. Policymakers struggle to work effectively in a cross-ministerial way. People who see themselves as “senior” resist rolling up their sleeves and actively engaging in participatory processes with other stakeholders. Response strategies often stick to the safe space of technical analysis and technical solutions ignoring how mindsets and power structures block transformational change.

These are challenges that organisations like ICIMOD and initiatives like Foresight4Food need to help tackle if foresight is to have a real impact on policy and local action.

Cultivating a cadre of foresight and systems change practitioners

Participants recognised there is a limited number of practitioners/professionals across the region who have the knowledge, skills and experience to effectively design and facilitate foresight and systems change processes. A big effort is needed to create a cadre of practitioners who do have these capabilities.

To tackle this gap, governments can develop foresight units, universities could make futures literacy and systems thinking part of their curriculum, and development organisations need to in invest more in such human capabilities.

Way forward

On the last day of the workshop, the “collective intelligence” of participants was used to start framing a new horizon scan for the region that could follow up on the highly influential 2019 HIMAP report on the region.

Participants left with many practical ideas of how they could apply the foresight thinking and tools directly to their work.

For ICIMOD and Foresight4Food hopefully, this was just the start of collaborating to strengthen regional capacities for foresight.

The energy and commitment of participants were astounding, especially given long days of challenging discussions.

All in all, it was a super inspiring week – giving hope that with committed people like those in the workshop, supported by organisations like ICIMOD, we can together create a more resilient and equitable future.

By Jim Woodhill, Lead Foresight4Food Initiative

Why do we need to transform our food system and how can foresight help?

The way food is consumed and produced is central to the polycrisis afflicting today’s world – said Ravi Khetarpal (APAARI), Amina Maharjan (ICIMOD), and Patrick Caron (University of Montpellier) in their keynote presentations at the 4th Global Foresight4Food Workshop.

The Foresight4Food Initiative held its fourth global gathering in the beautiful setting of BCDM Savar, Dhaka from June 3 to 7, 2024. Over 120 foresight practitioners from across 22 countries came together to share ideas and discuss the latest thinking on applying foresight to the challenges of transforming food systems. The event was hosted by the Government of Bangladesh and the Global Alliance for Improved Nutrition (GAIN) Bangladesh, with support from the Food and Agriculture Organization (FAO) and the World Food Programme in Bangladesh.

In a highly interactive week, participants engaged in a masterclass on foresight approaches, shared their experiences and lessons, heard from thought-leaders on food systems and foresight, and identified ways of strengthening foresight practice in their own countries and regions.

What does the future hold for our food systems?

Feeding the world contributes over 30% of greenhouse gases, and without change increasing population and wealth will drive this even higher. Meanwhile, diets are changing, often towards more unhealthy options. It is estimated that, by 2035, diet-related poor health could cost the global economy about 3% of GDP annually: this is the same negative impact that COVID-19 had on the economy. Environmentally, land use associated with food production is the main reason for the world’s massive loss of biodiversity and collapsing ecosystems.

And all of this is set against a background of increasing geopolitical tensions, and uncertainties for trade and access to resources.

As discussed during the different workshop sessions, foresight helps to understand the longer-term consequences of these trends, and the risks of “business as usual”. Even more importantly, participatory foresight and scenario development engages stakeholders in imagining how the future for our food systems could be different, in order to achieve sustainability, equity and resilience.

Highlights of the week included:

- Sixteen case studies on the use of foresight across Africa, Asia and the Middle East shared by participants – offering a wealth of insights, lessons and inspiration.

- Senior-level engagement from the Government of Bangladesh with insight into how foresight is seen as a key tool for helping to achieve their goals for food systems transformation.

- A deeper look at simulation modelling for foresight, and how a combination of qualitative and quantitative approaches can bring a range of important insights.

- Reflections on ensuring foresight processes are inclusive and consider gender dynamics.

- Six thematic sessions on cutting edge foresight issues which helped in mapping out a forward agenda for Foresight4Food.

- Strategic sessions on knowledge platforms and financing of food systems.

- Field trips where participants used insights from food system issues in Bangladesh to stimulate discussion on the future of the food system and sharing of cross-country lessons and experiences.

From my perspective, the key takeaways from the week were:

- The value of connecting foresight with a deeper understanding of the political economy of systems change, which is needed to help tackle the structural barriers to transforming food systems.

- Recognition of the critical importance of effective multi-stakeholder processes at national and local levels in driving food systems change, and the value of the foresight for systems change approach in supporting such processes.

- The necessity of increasing and reconfiguring investments in food systems and the need for this to be informed by the longer-term perspectives that foresight can bring.

- The value of integrating participatory foresight processes with quantitative modelling and use of data, while realising the constraints of limited food systems data at national and local levels.

- The importance of having foresight units and processes institutionally embedded in government, with a mandate and scope to challenge policy assumptions.

- A recognized need and growing demand for enhancing the capacities of policymakers, researchers and think tanks/consultants to design, facilitate and use foresight processes.

Participants left highly motivated to take forward the foresight work they are involved in and to help support the Foresight4Food network. The event ended with strong calls for the network to collaborate in helping to set up regional foresight support hubs across different continents.

By Jim Woodhill, Foresight4Food Initiative Lead

Last month (November 2023) I had the wonderful experience of engaging with over fifty young leaders from across Africa, joined by colleagues from Bangladesh, Nepal, and Jordan. We had all gathered in Naivasha, Kenya, to explore how skills in facilitating foresight can be used to help bring about food systems transformation.

The fascinating work these young leaders are involved in and their deep interest in understanding how to be more effective change-makers was truly inspiring. It was encouraging to see how valuable they found the foresight for the food systems change framework and the associated set of participatory tools for engaging stakeholders.

Participants all came with projects from their own countries where they are keen to use foresight and systems thinking to help facilitate change in food systems by bringing together different stakeholders. The participants were from diverse backgrounds representing policy, the private sector, NGOs, and academia.

A Guiding Framework: During the workshop we introduced participants to an overall guiding framework for facilitating foresight for food systems change. A range of participatory tools were used for systems analysis, development of future scenarios and exploring systemic interventions. To bring reality into the workshop, the Kenya horticulture sector was used as a case study for the foresight analysis. Participants spent a day visiting horticulture farms, packing and processing facilities and the local market. They explored with local stakeholders how they saw the future for the horticulture sector and the issues that “keep them awake at night”.

Visualising the system: The workshop was highly interactive with participants practicing in the facilitation of a range of participatory tools which can be used to bring stakeholders into dialogue around systems change. One of my favourite participatory tools “rich picturing”, which enables a diverse group of stakeholders to develop a shared understanding of a system by drawing it, was found by participants to be especially powerful.

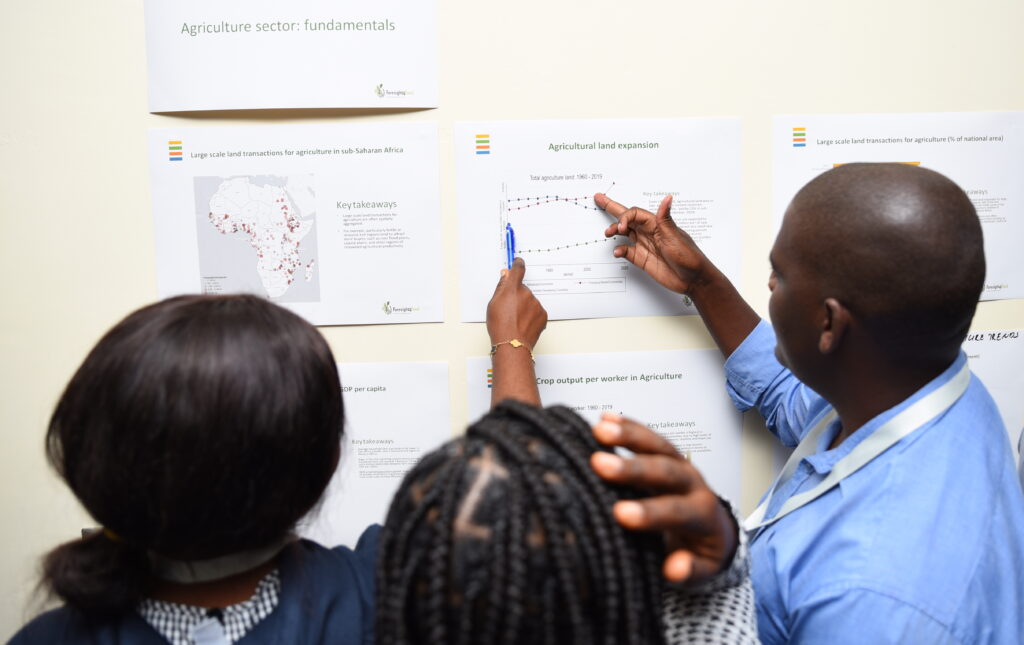

Data-driven dialogue: To go deeper into the systems analysis it is valuable for stakeholders to explore the available data on key drivers and trends. Over 100 graphs visualizing key data points related to the Kenya horticulture sector and food systems at national, continental, and global scales were collated and posted around the walls. The participants then explored this data in groups of three and discussed its implications and how it perhaps challenged their existing assumptions.

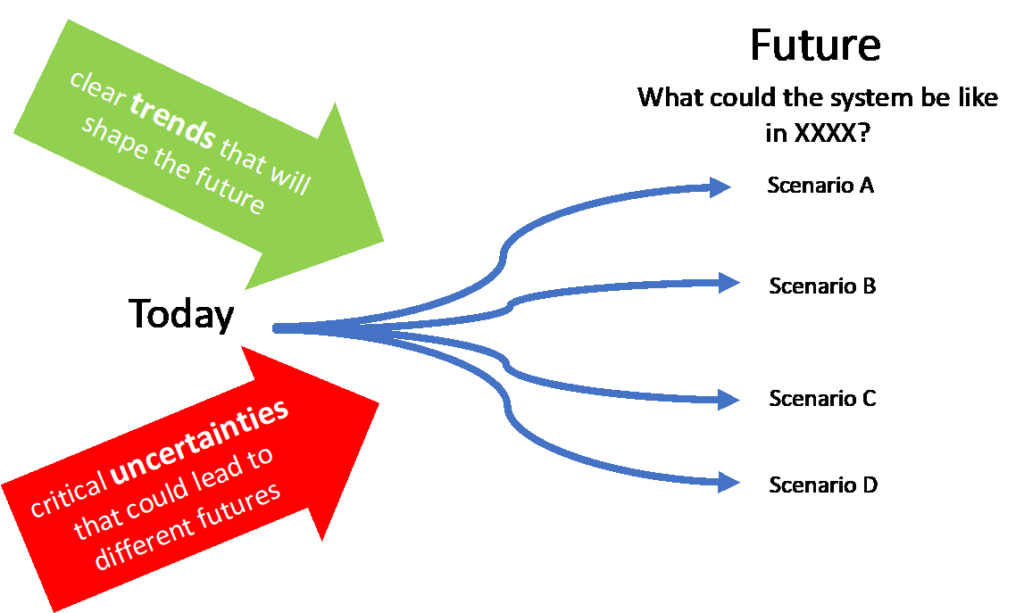

Exploring the future using scenarios: Central to the foresight approach is developing a range of different plausible future scenarios (generally with a 10 to 30-year horizon) for how the system might evolve given critical uncertainties. Workshop participants did this for the horticulture sector, looking at factors such as how diets might change in the future, regional and global trading relations, severity of climate change, and the enabling policy environment for small-scale producers and the small- and medium-scale enterprises (SME) sector. The scenarios help to identify future risks and opportunities for different stakeholder groups and society at large. They also help to unlock creative thinking about how to “nudge” systems towards more desirable futures and away from less desirable ones.

The deeper issues of systems change: It is easy to talk about systems change. In reality trying to change systems bumps into all the difficult issues of vested interests, power relations, ideologies, and deeply held cultural beliefs. On top of this human and natural systems are complex and adaptive and behave in self-organising, dynamic, and often unpredictable ways. It doesn’t mean you can’t intervene to try and bring positive change. But it does mean that top-down, linear, and mechanistic models of change generally don’t work. The workshop engaged participants in deep and challenging discussions about what it means to be a leader of systems change. This included the need to be adaptive, how to create alliances for disrupting existing power relations, the importance of building relations between diverse stakeholders, and the importance of patience. Systems change often requires taking time to build the foundations for change without being able to know when circumstances might suddenly unlock opportunities for big steps forward.

Identifying directions for change and intervention options: Developing directions and pathways for systems change is the most difficult and challenging part of the foresight for systems change process. It is highly context-specific and requires a deep insight into the political economy of the situation. Cause and effect mapping, theory of change thinking, and causal loop analysis can all help in identifying opportunities for intervening which could help to drive systems change in desired directions. Bringing change will often require an integrated approach to technological, institutional and political innovation. During the workshop causal loop diagrams were used to explore possible entry points for shifting horticulture systems in ways that could improve health, livelihoods and the environment.

New friends, new networks and big ambitions: After an intense week of learning and sharing participants left inspired to apply the foresight approach back in their own work environment. New friends were made and there were clear calls to find mechanisms to support ongoing networking and peer support.

Many thanks to the facilitation and support team who made a fantastic week possible, Gosia McFarlane, Marie Parramon-Gurney, Kristin Muthui, Bram Peters, Joost Guijt, Riti Herman Mostert, and Abdulrazak Ibrahim. The event was made possible by support from the Mastercard Foundation.

More information about the Foresight4Food Framework of Foresight for Food Systems Change can be found on our website, and an updated approach paper will be published in January 2024.

By Jim Woodhill, Lead Foresight4Food Initiative

How can we understand the multiple dimensions of transforming food systems? On top of the disruptions to peoples’ incomes and food supply chains caused by COVID, the Russia war in Ukraine has pushed fertilizer, energy and food prices to all-time highs. Millions are falling back into hunger and poverty. Even in the affluent world, many poorer people in society are being forced to use food banks, eat lower nutritional value food, and make tough decisions between using their dwindling financial resources to pay for food or keep their houses warm in winter.

This situation underscores the conclusions of the UN Secretary General’s 2021 Food Systems Summit that highlighted the need for a far more resilient, equitable and sustainable food system. Heads of state universally declared that a transformation of food systems is needed to cope with climate change, tackle hunger and poor nutrition, reduce poverty, and protect the environment.

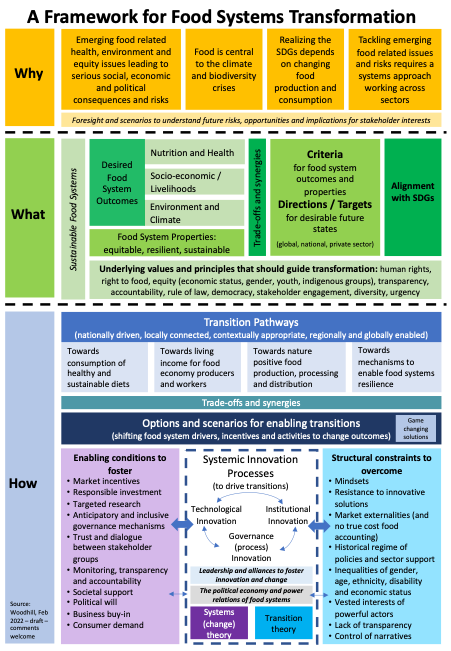

But what does food system transformation actually mean? In this blog, I outline a framework (Figure 1 below) for thinking about food systems transformation. It is based on WHY change is needed, WHAT needs to change, and HOW change can be brought about.

Introducing food systems transformation

“Food systems” has provided a new framing for a more integrated approach to the issues of food security and nutrition, agriculture, climate change, environment and rural poverty. This systems view makes a lot of sense as, one way or another, how we consume and produce food is central to all the Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs). Billions of people work in the agri-food sectors, everyone needs a healthy diet, food is central to culture, food trading and retailing are huge markets and agriculture is the biggest user of land and water resources.

This systems perspective is bringing together a plethora of associated ideas, language and concepts. Terms such as food system outcomes, transformation, transition pathways, resilience, equity, trade-offs and synergies, living income, nature positive approaches, agroecology and the true-cost of food are just a few of these. The emerging food systems discourse is also giving more attention to power structures, the political economy, stakeholder engagement and dialogue, empowering excluded voices, market externalities, coalitions, economic incentives, and data needs.

Before explaining the framework, let’s ask what is meant by a transformation of food systems. Transformation means a complete or radical change of something in form, function or appearance. So, transforming food systems means fundamentally changing how they operate to dramatically improve environmental, health and livelihood outcomes for society at large. This requires fundamental changes in the behaviour of consumers, investors, agri-food sector firms, farmers, researchers and political leaders. In turn, a dramatic shift in economic and social incentive structures is needed, with the true cost of food embedded into how markets function. To avoid future risks these fundamental changes are needed with urgency.

To-date, and perhaps not surprisingly, much of the debate and political narrative has focused on what needs to change and why. The more difficult question of how change can actually be brought about has so far received less attention. Perhaps this is because such discussion cannot avoid difficult political-economic issues of long-term collective interests versus short-term vested interests. We are still a long way from having sufficiently detailed strategies, plans of action, policy commitments and investments to bring about the transformation. How to get from WHY to HOW?

WHY transform food systems?

Why food systems need to change has been well analysed, is clear to most stakeholder groups, and is increasingly articulated by political leaders. The problems and longer-term impacts and risks of the way food is currently consumed and produced is well-evidenced in terms of the negative consequences for health, the environment, and equitable economic development. If this interconnected set of issues is not tackled effectively and promptly the risks of dire longer-term social, economic and political consequences are high.

Food value chains contribute about a third of total greenhouse gas emissions. Agriculture and fishing are by far the largest causes of biodiversity loss and ecosystem degradation. These impacts on the environment cycle back to undermine the Earth’s very capacity to produce food for the long run.

Further, it is increasingly clear that the SDGs and in particular SDG1 – no poverty – and SDG2 – zero hunger – will not be achieved without a fundamental change in how food systems function.

The work of the Food Systems Summit brought a much wider understanding and acceptance that the numerous development issues linked to food can only be effectively dealt with through a cross-sectoral and systems-oriented approach. An additional critical aspect of the food systems framing is an acceptance that these issues are of equal importance for countries in the Global North and the Global South.

Foresight and scenario analysis can make a vital contribution in helping to explore the ways food systems might change and with what risks and opportunities for different stakeholder interests.

WHAT needs to be transformed?

The desired outcomes from food systems have become well-articulated in terms of three main areas:

- ensuring food security and optimal nutrition for all.

- meeting socio-economic goals, in particular reducing poverty and inequalities.

- enabling humanity’s food needs to be met within planetary environmental and climate boundaries.

Overall, food systems are recognized as needing to function with the properties of being resilient to shocks, sustainable over the long-term and equitable in terms of the costs and benefits to different groups in society.

Across these food system outcomes and properties, there are inevitable trade-offs and synergies, which bring with them the potential for both conflict and collaboration between different interest groups. While the broad directions for desired food system outcomes and properties are relatively well established, the nature and extent of these synergies and trade-offs is much less well understood. More work is also needed to establish specific criteria, directions for change and targets for food system outcomes, which will be necessary to guide transformation at national or local levels, within sectors or across business operations. More attention needs to be given to how the criteria and targets for food systems transformation align with those of the SDGs.

The Food Systems Summit and the work of the Committee on World Food Security (CFS), in particular its recently adopted Voluntary Guidelines of Food Systems and Nutrition (VGFSyN), have identified underlying values and principles that should guide the processes and outcomes of food systems transformation. These include human rights (incl. the right to adequate food), sustainability, resilience, transparency, accountability, adherence to the rule of law, stakeholder engagement, gender equality, and inclusivity (particularly for women, youth, indigenous groups and small-scale producers).

Food systems that deliver on the desired outcomes and properties, and function in adherence with the underlying values and principles articulated above, can be considered as sustainable food systems.

HOW can food systems be transformed?

The transformation of food systems will require a focus on transition pathways, largely driven at the national level but connected with local processes and enabled by larger-scale system shifts at regional and global scales. Four main transitions can be identified from the Food Systems Summit deliberations:

- a consumption shift to sustainable and healthy diets.

- an equitable economic shift to ensure food economy producers and workers, have a fair living income including being able to afford healthy diets.

- a shift toward nature positive approaches for food production, processing and distribution which have a net-zero climate impact and operate within a sustainable and safe zone of utilizing natural resources.

- a shift towards mechanisms of resilience for food systems which can ensure societies a large to not risk food insecurity and that groups who are poor or vulnerable are protected.

Desired food system outcomes can potentially be achieved through multiple different pathways and scenarios with numerous different trade-offs and synergies. For example, consumption shifts could be influenced by food prices and taxes, public education, product labelling or shifts in food marketing practices. Resource efficiency and circularity could be achieved by a number of measures, including consuming (at a global level) less animal protein, adopting agroecological approaches, energy efficiency, water management, reducing waste, or new technologies which reduce methane emissions from cattle farming. Equity for those working in the sector could be improved through various combinations of increasing food prices, implementation of labour and land tenure rights, improved social protection, improving overall rural economic development or creating greater economic opportunity outside the food sector.

Developing and assessing the options and scenarios to enable transitions is where a vast amount of investment and work is needed if food systems are to be sustainably transformed. The Food Systems Summit process identified a significant number of “game changing solutions”, ideas that could contribute to developing viable transition pathways. Further assessment and work will be needed to refine, prioritize and build on this contribution from the Summit.

Scenarios can help identify potential trade-offs and co-benefits of those solutions across intended food system outcomes. The principles of equity and inclusion are especially important to consider when analysing options and trade-offs. For example, gender equality is not guaranteed to improve with increased income from food systems activities, so attention must be paid to gender-transformative and inclusive value chain development.

Generating viable options for transforming food systems will require systemic innovation that connects processes of innovation across the domains of technology, institutions and social norms, and politics and governance. Food systems transformation will be impeded or enhanced depending on the constellation of power relations across societies and the agri-food sector. This is particularly salient where influential actors are prepared to defend vested interests at the cost of changes for the wider collective good. Such systemic innovation will require profound paradigm shifts and completely new approaches to policy coherence.

Insights from systems theory and transition theory have much to offer in terms of how to guide and broker change in complex (food) systems. For example, encouraging, supporting, linking and scaling up “niche” innovations that can respond to new needs, challenges and opportunities. This requires adaptation to local contexts that can be supported by territorial approaches to development. Over time, such innovations can help to disrupt existing and unsustainable food systems “regimes” (attitudes, policies, power relations, market relations) and enable more sustainable alternatives to become embedded.

The Food System Summit has helped to identify numerous factors that can be considered as enabling conditions or structural constraints for food systems transformation. Systems change involves “nudging” systems in desirable directions by working to amplify enabling conditions and dampening structural constraints. This requires attention to the underlying political economy. Strategic alliances and political leadership are needed to help shift understanding, narratives and power dynamics.

By Jim Woodhill, Lead Foresight4Food Initiative

A dramatic and rapid transformation of food systems is necessary to end poverty and hunger, protect the environment, improve rural livelihoods, and ensure resilience to future shocks. This transformation must include structural changes in how our political, economic, social and technological systems function. Such transformative change requires a long-term perspective and understanding of the risks and opportunities in different possible food system futures – the purpose of foresight.

Foresight and Food Systems

Foresight offers one approach to support transformational change for a more equitable and sustainable global food system. It uses futures thinking and scenario analysis to help diverse food system actors (e.g., rural farmers, food manufacturers, small agri-food businesses, governments) imagine, together, how the future might unfold. Considering future scenarios enables possible risks and vulnerabilities to be understood and mitigated. It also enables opportunities for positive food systems transformation to be identified and explored.

Foresight analysis helps to create understanding about how key trends and critical uncertainties (e.g., changing diets, climate impacts, demand for certain foods) could impact food systems. It supports preparedness for different possible futures.

Food systems are extremely complex, with all of the activities of food systems from production to consumption affecting global health and nutrition, environmental sustainability, and livelihoods and employment. Globally, agri-food work is the largest economic sector, employing over a quarter of the world’s workers. The scale alone of global food systems makes achieving change complicated and slow. Fear of the unknown, combined with vested interests of powerful food systems players, can bring resistance to innovation and change. This results in a lack of effective responses to already pressing issues. The challenge Is compounded by the difficulties of creating sufficient collective understanding and commitment among the highly diverse groups involved in food systems.

However, while change often seems slow and difficult, stuck or even regressing, there are endless positive examples of individuals, communities, groups and organisations working for more sustainable and equitable food systems. Especially when the life force of food is involved, people are deeply capable of innovation, creativity, social organisation and activism.

However, while change often seems slow and difficult, stuck or even regressing, there are endless positive examples of individuals, communities, groups and organisations working for more sustainable and equitable food systems. Especially when the life force of food is involved, people are deeply capable of innovation, creativity, social organisation and activism.

While foresight and scenario analysis is no panacea to the complex and overlapping issues within our food systems, it offers two critical contributions:

- Motivation and clarity for change by offering stakeholders a window into the future, through which they can see how their longer-term interests and aspirations would be affected by different future scenarios.

- Helping break down the barriers of vested interests by facilitating stakeholders to collectively explore options and pathways for change that can balance individual and common interests.

The Foresight4Food Approach

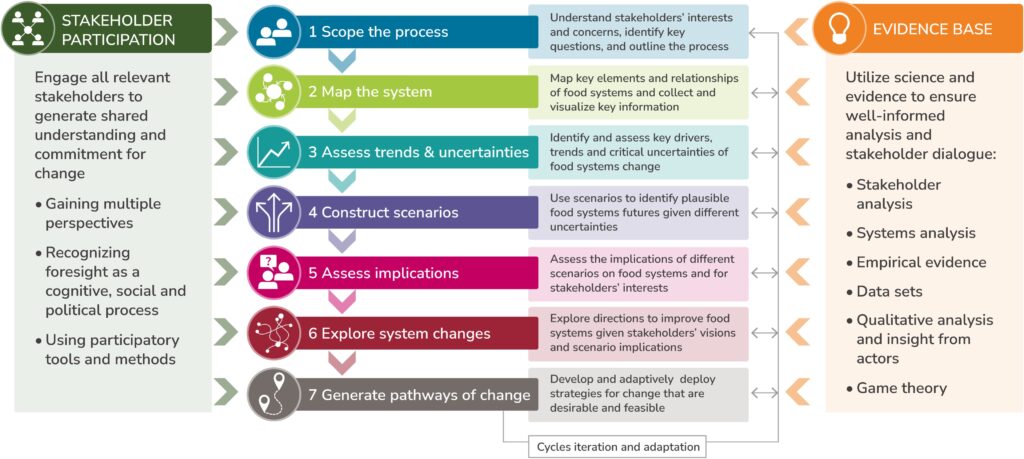

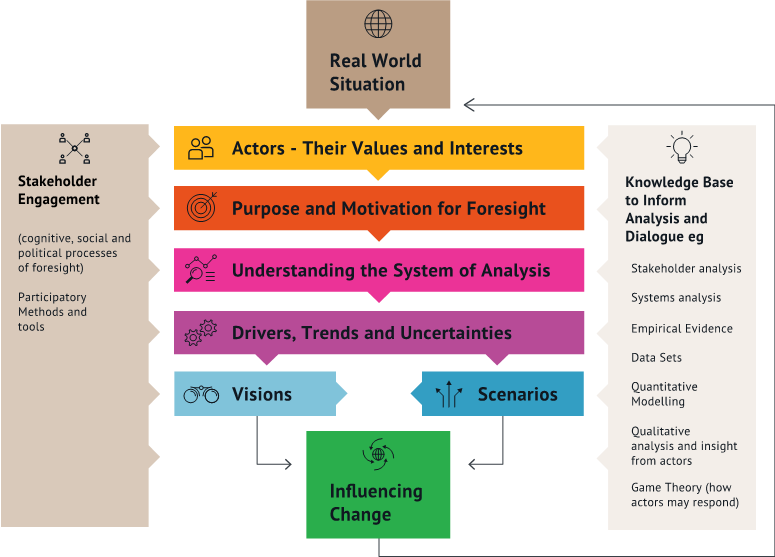

The Foresight4Food Initiative has developed a framework and process to guide foresight and scenario analysis for food systems change. The framework (Figure 1) links a participatory process of stakeholder engagement with a strong scientific evidence base and the use of computer-based modelling and visualisation. The approach starts by understanding how food system actors “see” the food system – their actions, values and interests – and their motivation for engaging in foresight. It maps out and examines how social, technical, economic, environmental and political (STEEP) factors interact within food systems, and how food systems are influenced by the power dynamics between actors.

A food systems framing is critical to identify and assess key drivers, trends and uncertainties, to develop alternative future scenarios (Figure 2). The approach creates dialogue between stakeholders about their assumptions on how the future food system may unfold and what this implies for their visions and aspirations. The discussions that ensue provide a foundation for exploring what directions for food systems change would be in the collective interest and how trade-offs or synergies between the specific interests of different groups can be best managed.

Central to this approach is the development and analysis of future food system scenarios, based on data about key trends and critical uncertainties. This is often the most challenging yet insightful part of the process. It takes various actors ‘outside the box’ to imagine how the future of food systems could be fundamentally different, with what implications.

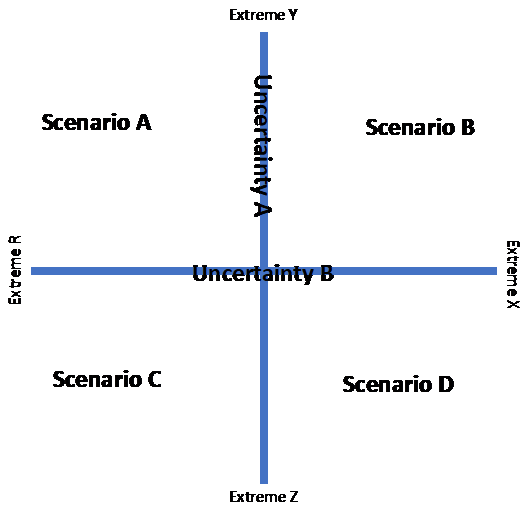

A simple way to develop scenarios is to identify two independent critical uncertainties that then create a matrix of four different scenarios (Figure 3). For example, critical uncertainties in food systems could be dietary changes, climate impacts on agricultural production, malnutrition levels, market and trade functioning, and many others. Scenario story lines are then developed that outline what each of these four futures would be like, based on the two chosen uncertainties. ‘Back casting’ is used to look backwards from an imagined future scenario to construct the possible events and decisions that could have led to such a future.

The framework integrates four elements:

- A futures orientation that invites stakeholders to develop a longer-term perspective on how food systems may unfold in the future, and what decisions are needed today to avoid future risks and build resilience into our food systems.

- Ways of thinking about how change happens in food systems – by linking theories and schools of thought on complex systems, socio-technical transitions, wicked problems, anticipatory governance, cognition, and human bias.

- Practical methods from strategic foresight, scenario planning, multi-stakeholder processes, soft systems analysis, and theory of change.

- Participatory tools for analysis and group facilitation, which enable food system actors to collectively analyse situations and data, create scenarios, engage in dialogue and critical conversations, build trust, and generate pathways of action.

Rethinking Food System Change

Foresight4Food’s approach recognises that elements in the system (i.e., people and nature) interact in complex and adaptive ways; therefore, change in food systems does not occur in easily predicable or linear and hierarchically controlled ways. The complex nature of food systems deeply challenges reductionist mindsets that continue to dominate in public policy making and organisational management. Food systems thinking recognises that change happens through nudging systems, rapid experimentation and learning, and scaling niche innovations. It explores how locked in structures and power relations can be disrupted, yet recognises that building the foundations for desired change takes time, with the eventual outcomes and moments of change being uncertain.

Food systems transformation will require ongoing innovation and learning, with strong networks to obtain feedback and decentralised responsibilities for decision-making and action. Real changes in food systems will depend on shifting underlying structures related to power dynamics, relations between different actors, and the mental models of society, leaders and politicians. Foresight and scenario analysis can help to surface and examine these dimensions of change in a complex and adaptive food system. It is an approach to help generate the critical thinking, leadership and stakeholder engagement needed for food systems transformation.

By Jim Woodhill, Ken Giller and John Thompson

The final eDialogue in our five-part series on the ‘What Future for Small-Scale Farming?’ finished off by exploring policy implications for the inclusive transformation of small-scale agriculture in challenging times.

A stellar panel of experts from five continents brought a rich and insightful set of perspectives to the table.

We asked: “Is a fundamental shift in incentives and policies needed to tackle the ongoing issues of poverty and malnutrition facing rural-households who farm, and to align small-scale agriculture with the goals of a transformed food system? If so, how might such shifts be brought about?”

Rhetorical questions perhaps, but it was enlightening to hear from a group of highly knowledgeable panellists that profound shifts in policy are needed and that such change is possible, despite the difficulties. The need for new visions of policy goals, that take a much more integrated approach to food systems was a clear message.

It was also clear that policy does matter. Current incentive structures and market externalities are often driving food systems and the conditions for small-scale farming in the wrong direction. Past policy settings may have been appropriate for a staple crop-oriented approach to food security, prior to times of resource scarcity, climate change, the growing nutrition crisis, and more complex rural-urban interlinkages. Today, however, emerging challenges and future risks require a substantial policy rethink.

Against a backdrop of ‘progress’, too many people are being left behind: Given a set of mega-trends, we were encouraged to be optimistic about the future. Taking Africa for example, wage rates, education levels, health status, financial inclusion, access to mobile phones, and off-farm employment rates have all improved dramatically and appear to be heading in the right direction. However, this does not mean that specific groups aren’t being left behind or that there aren’t fundamental challenges in the food and farming sectors related to livelihood security, health and nutrition and the environment. These are very real challenges that affect large numbers of the most vulnerable male and female farmers, and farm workers, and they require substantial policy innovation. This wider positive development trajectory does though give hope for change. However, linking back to the theme of ‘recognising diversity’, what is possible is profoundly shaped by a country’s specific economic status and its particular political economic dynamics.

Recognising good public benefits: It was observed by the panel that farming and food is a largely a private sector activity. Yet, depending on the way food systems are functioning, the outcome can lead to huge public good benefits or costs. Basic, public investments in agricultural research and development, and in ensuring rural infrastructures such as roads and communication along with the right incentive mix for good health and environmental protection are foundations for society to reap benefits rather than costs from the ways we produce and consume food. Deeper discussions about public costs and benefits, both in the short and longer-term and how they link to market failures and incentive structures is a critical starting point, for the transformations that are increasingly recognised as necessary.

Working backwards from a new vision for food systems and rural economies: Arguably, policies related to small-scale farming have focused too narrowly on immediate issues rather than longer-term visions for change. The food systems agenda creates an opportunity to rethink small-scale farming within a wider context of creating visions and transformation pathways for food systems that are oriented towards improved livelihoods, good nutrition, environmental sustainability, and that are economically inclusive. This ties into utilising what will be substantial growth in the value of both domestic and regional food markets to help drive wider rural economic development. But all this requires longer-term and more integrated and dynamic policy thinking that works back from these visions of possible ‘food futures’ to the policies, practices and programmes that are needed to guide the transformation. At the same time, the risk and uncertainty of such complex and dynamic socio-technical systems must be recognised. Linear management and control approaches to policy are increasingly ineffective. Framed by a risk-based approach, our institutions and policies are often poorly equipped for our uncertain world.

An enabling pathway for ‘small food system entrepreneurs’: An underlying message was that the future for many small-scale producers will most likely not be as farmers, but rather as ‘small-scale food system entrepreneurs’, generating income and employment opportunities from diversified sources both on and off the farm. Policies are needed to support this entrepreneurial transition and capture the value from food markets to help drive wider rural economic development.

Responding to vulnerability: Future policies must prepare for and be able to effectively respond to the increasingly complex, intersecting social, economic, and environmental vulnerabilities faced by farmers and farm workers. COVID-19 has well illustrated the devastating impact of the pandemic on household incomes and their ability to purchase sufficient healthy food. The climate crisis is likely to dramatically increase the risks of droughts, natural disasters, disease outbreaks and even conflicts, all of which disproportionately impact on small-scale producers. This uncertain context with its overlapping short- and long-term shocks and stresses, presents a complex set of challenges for food and farming policy, demanding more adaptive, experimental, reflexive forms of governance and institutional arrangements. This call for much more innovative forms of affordable insurance schemes and risk-oriented social protection.

Territorial innovation: Forget the notion of large cities and rural areas. Increasingly populations are spread across a vast number of towns and small- and medium-sized cities, creating vast peri-urban areas and stronger rural-urban connections. This creates tremendous opportunities for small-scale farmers, both in terms of new market linkages and value addition, but also in terms of off-farm employment opportunities that can complement farm income. However, at national and sub-national scales, tailored policies are needed to support such territorial development and the often unique conditions of different locales.

Land reform and inequality: Equitable land access and rights that balance the needs and interests of small-scale farmers with small-holder commercialisation and the development of larger-scale farming remains one of the most critical aspects of policy. Land policies have a profound influence on gender equality and empowerment, the rights and livelihoods and vulnerable groups, and investment by both small-scale farmers and larger operators. The world is seeing an increasing polarisation between consolidated large-scale agri-food sector investments and small-scale family farming which risks growing inequalities and difficulties in creating a more economically inclusive food system. Policymakers need to come to terms with the sort of land and investment policies that can better balance food system outcomes of health, equitable livelihood opportunities and environmental sustainability.

Cultural identity: Farming and rural lives are about peoples cultural identities. Policies need to be careful of instrumental approaches that ignore the cultural connections with land and the role that food plays in culture and identity. These factors also have a significant role to play in the decisions farmers take and the importance of land beyond pure economic returns. Empowering rural groups to express and strengthen cultural identities that help maintain social cohesion solidarity should not be overlooked.

Access to capital: Although access to land matters, equally important for many households is credit and longer-term investment funds. For all the talk of rural banks and micro-finance, most small farmers simply cannot get working capital. They rely on whatever they have as ready cash which often must be spent on pressing priorities, such as school fees, medical bills, and household consumption. Thus, many small farmers struggle to buy quality inputs or hire labour when they need it the most, and in the process forego yields they can ill-afford to miss.

Fundamentally perverse incentives: Our panellists left no doubt that past policy decisions that have resulted in a set of deeply perverse incentives, at both the global and domestic scales. Too often existing public expenditures drive towards the production of calorie-rich rather than nutrient-dense foods and put ‘band-aids’ on poverty rather than enabling the conditions for rural economic development. Current subsidies drive unsustainable use of natural resources or distort trade to the disadvantage of small-scale farmers. The extent to which small-scale farmers receive public support varies enormously among continents and countries. In South Asia, where public support to rural households is multi-layered, a wider view of how policies impact on food prices makes it clear that small-scale farmers are often ‘net taxpayers’. Essentially, they subsidise cheap food for consumers and value extraction by more powerful enterprises further along the food value chain.

Beyond “subsidies” to investing for the public good: Panellists stressed the point that the right kind of targeted subsidies can make a difference to agricultural productivity and livelihood security. While the pros and cons of input and price subsidies have been hotly debated over the past decade, a rethink around the language of subsidies is needed. Given market externalities, the huge public costs and risks of a failing food system, widespread rural poverty and inequality corrective public good investments are essential. These include for example creating incentive mechanisms to drive the demand for and production of a diversity of more nutritious food, incentives for good environmental practices, ensuring rural infrastructure, or improving social protection schemes, particularly in relation to risk. The challenge is to design so-called ‘smart’ subsidy programmes that have a significant impact on the availability of food and the improvement of household incomes in the short run while stimulating growth and rural development and increasing (or at least not suppressing) effective demand for and commercial distribution of inputs in the long run.

Political realities: No one should be naive about the political imperative of keeping food prices low and ensuring national food security. For a majority of people in low- and middle-income countries food is a large proportion of their expenditure and even slight rises in food prices can easily push them into a food deficient situation and dramatically impact on their ability to pay for other life needs. As was well seen in the 2008 food prices crisis, this has significant implications for social and political stability, something of which most governments are acutely aware. Further, many poor farming households are net purchasers of food. Consequently, governments are often very risk-averse in terms of changing policies that relate to food prices and food security. Further, the existing regimes of input and price subsidies have significant benefits for some, often influential, interest groups who bring their influence to bear in maintaining the status quo.

Practical realities: As one panellist highlighted, even with strong political will to reform food systems, incentive structures and how these impact on small-scale farmers, there are significant practical challenges. In general, more effective use of public investment requires effective targeting to the needs of specific communities and households in specific locations, often involving direct cash payments. However, many of those who need such support do not have bank accounts. There are huge data gaps in knowing who to target in what sort of ways and significant administrative challenges. This is one of the reasons more broad-based approaches are often used, despite the challenges of a distorting influence, poor targeting, and leakage of resources.

Mobilising political commitment for change: There is a tendency for people (and governments) to overplay the risks of doing something differently and underplay the risks of the status quo. Consequently, policy innovation and reform to drive the transformation of small-scale farming within a broader vision sustainable and socially-just food systems require four things: One, a clear perspective of the negative consequences of ‘business as usual’ that is understood not just by a small network of informed researchers and activists, but by political leaders of all stripes and wider society (after all, we are all consumers of the goods and services provided by our food system). Two, evidence that alternative pathways can work, based on sound research and detailed case studies documenting the emergence and persistence of ‘islands of innovation’ to provide ideas and inspiration for future policy and practice. Three, practical transition strategies to bring about change and which can balance out the interests of the ‘winners’ and ‘losers’ and ensure ‘no one is left behind’. Finally, sufficiently strong international and national coalitions for change from across government, business, civil society, and science are required. Global public goods need to be invested in helping to generate the data and evidence, and the informed processes of dialogue and coalition-building necessary for change. Such processes are needed from local to global in ways that help to link understanding of how issues connect across scales. Of critical importance is building national and local level capability for generating and synthesising data and supporting stakeholder and policy dialogue with foresight and scenario analysis.

Farmers voices: The fundamental importance of engaging farmers themselves, with all their diversity, in policy dialogue was underscored. This is vital for understanding what farmers are actually experiencing, hearing their ambitions and ensuring they are able to protect their interests. Inclusive processes of policy dialogue from local to global levels need support and investment.

——————————–

Acknowledgement: This blog drew in particular from the comments and inputs of the panellists of the fifth session of the eDialogue and we are very thankful for their rich contribution to the discussion. The blog is the authors’ interpretation of the session and may not necessarily represent the overall perspective or specific opinions of the individual panellists.

Panellists: David Nabarro, Meike van Ginneken, Thomas Jayne, Elena Lazos Chavero, Rebbie Harawa, Ángela Panegos, and Avinash Kishore

By Jim Woodhill, Ken Giller and John Thompson

Tuesday 10 November was another fantastic session of our eDialogue series on ‘What Future for Small-Scale Farming?: Inclusive Transformation in Challenging Times’.

The panellists explored the complementary roles of commercialisation, food production for self-consumption and social protection in tackling farming household poverty and poor nutrition.

Now with four eDialogue sessions under our belt, a set of very thought-provoking perspectives are starting to crystallise. They have profound policy implications.

Achieving the SDGs hinges on transforming small-scale farming. Let’s step back to the fundamental issue. The world has an estimated 500 million small-scale farmers. In terms of rural households this represents a population of some 2.5 – 3 billion people – over a third of the world’s population. On the one hand, this group produces much of the food consumed in low- and middle-income countries. On the other, this group encompasses the majority of those who still live in extreme poverty and suffer hunger. A transformation of small-scale farming is fundamental to eradicating poverty and hunger, to feeding the world sustainably and well, and to tackling the climate crisis.

Small-scale farming households are very diverse. In thinking about this necessary transformation, our eDialogue panellists time and time again stressed the point that small-scale farmers are not a homogenous group. We often hear it said that there are no “one size fits all” solutions. We would go further and say that generalisations are not only misleading, they can be very dangerous and lead to ineffective policy directions and sub-optimal outcomes.

Gender dimensions are critical. In understanding household diversity, it is critical to understanding the roles and changing role of women. For example, as male members of households seek employment outside the farm, either locally or further afield, the women take on greater farming responsibilities, but often without commensurate decision-making power, access to finance and expertise and security of land tenure. Women’s and girls’ empowerment remains a critical element of any transformation strategy for small-scale farming.

Most small-scale farming households don’t just farm. It is vital to recognise that rural households who farm are not only farmers. Farming households have a diversity of income sources. Household members engage in a combination of farming, off-farm micro-enterprises, rural wage labour, and migrating to work in urban areas. Poorer households may also rely on various forms of social protection. A shift of perspective is needed from “small-scale farmers” to “rural households who also farm”, recognising that farming is often just one of several important income streams.

The number of small-scale farms are not declining as economies develop. There is another critical observation. In OECD countries, economic development during the 20th Century saw a very rapid decline in farm numbers and significant land consolidation. Although there is a trend towards consolidation of farms in some countries of East Asia, this is not happening in most low- and middle-income countries. In fact, in South Asia and Africa farm numbers are increasing and farm sizes are shrinking, while perhaps counter-intuitively in parallel there is also an increase in the number of medium-sized farms. Two factors are at play. First, increasing populations without commensurate employment opportunities create an increasing demand for land. Second, without employment security, social protection, health insurance or pension schemes, many people hang on to their land as security. This occurs even if the land area is very small and even when they have substantial off-farm income. This situation is also leading to forms of informal and temporary land leasing and consolidation, in ways that enable people to maintain their legal or customary title.

Most small-scale farmers can’t make a living from farming. Against this background, we need to understand the profitability of farming. The harsh reality is that for many farmers growing staple crops – or even traditional cash crops such as coffee and cocoa – on small areas of land it is hard to make a living, given the low productivity and current market prices. Production of low-value commodities on small parcels of land generates small, often negligible, surpluses that make it difficult for the household to cover the basic income requirements for daily living. Some crop sales by poor semi-subsistence households are, therefore, not sales of surplus, but so-called “distress sales” to meet immediate cash needs, even if the household then has to buy in quantities of the same crop a few months later – when prices are higher. This makes livelihood diversification essential. Very small-scale farmers who are unable to diversify their livelihoods remain the poorest and most malnourished group of people on the planet.

On its own, linking farmers to markets is not a solution. The last decades have seen a development ethos around the idea of linking farmers to markets and agricultural commercialisation as a core strategy for tackling rural poverty. On its own, this focus on ‘making markets work’ is not a solution for the complex challenges faced by a majority of small-scale farming households. There is a reality of how much can be produced on a given area of land. With the very small land holdings many farm families maintain, the numbers simply don’t add up for the many crops they grow and the prices they receive for their produce. It is not a question of investing in “sustainable intensification” to increase yields by 20, 50 or even 100 percent nor of improving prices by similar amounts. Most small-scale farmers would need a multifold increase in farm income to get anywhere close to a living income. Without doubt, connecting to markets is important, but only part of the issue. It is what can be earned from producing for markets from a given area of land combined with other sources of off-farm income that ultimately matters.

A Pareto Principle for small-scale farming? The economic value of growth in the food sector will be very substantial over the coming decades. This leads to the argument that there will be significant opportunities for small-scale farming households in agriculture. However, this assumption needs to be unpacked carefully. It is already clear that a small minority of larger, more viable small- and medium-scale farmers produce the bulk of food being consumed by urban populations. Future demands for food will be for high-value perishables and will have requirements for quality, safety, traceability and volumes of delivery which create substantial barriers for most small-scale producers. The degree to which future food demands will be inclusive and translate into viable futures for large numbers of more marginal, small-scale producers is questionable at best.

Food system opportunities beyond the farm. Growth in food demand can help to drive overall rural economic development and create a diversity of both on- and off-farm employment and enterprise opportunities. The pathway out of poverty for many small-scale farmers is most likely through diversified livelihood strategies where they become more integrated into off-farm economic activity and much greater levels of value addition. In the medium term, many will take up these opportunities while still doing some farming. The scale of off-farm food system employment opportunities along and beyond the value chain needs to be better understood. These are the places likely to create multiplier effects in the wider rural economy to drive structural transformation.

Don’t forget informal markets. While some supply chains are formalising, for the foreseeable future informal and semi-formal markets will dominate domestic food trade in most countries. They have supply networks that may stretch over great distances. At the consumption end, these systems meet the growing demand for prepared foods, with the role of women and youth being particularly important throughout. Optimising inclusive on and off-farm economic opportunities in these markets is essential for reducing rural household poverty. Policies need to be geared towards supporting more pluralistic arrangements, strengthening both informal and formal marketing channels to meet the growing demands of a diverse set of rural and urban consumers. At the same time, it is important to recognise that employment and trading conditions in the informal sector can be very exploitive, making it difficult for people to escape poverty and move towards a living income.

The need for holistic approaches. Tackling the poverty, food insecurity and malnutrition faced by many rural households whose livelihoods largely or partly depend on farming will require a multi-pronged and integrated approach. Strategies need to be targeted to the specific circumstances and needs of particular households and particular geographic locations. Broadly, four elements need to be integrated into a coordinated approach:

- Enabling inclusive commercialisation opportunities for those who have the potential for farming to be a viable element of their livelihood mix, with a particular focus on diversifying production systems to support more nutrient-rich diets.

- Optimising the potential for farming households to improve their nutrition and food security through what they can produce for self-consumption.

- Extending, targeting and innovating social protection to support those who are most vulnerable, to provide better risk management and insurance mechanisms and to support people to become economically active and self-reliant.

- Creating enabling conditions for farming households to diversify into off-farm income earning activities.

An enabling rural environment remains critical. Alongside initiatives that target the needs of individual households, there is also a need to put in place the public goods and services, including infrastructure, telecommunications, energy, education and health services, and sustained business investment and dynamic small and medium-scale enterprises which are needed to underpin the overall economic development of any rural area. Striving to create a vibrant rural environment where people actively choose to live – including young people – is key for the long-term future.

Getting the data. The eDialogue posited many observations about the trends and emerging opportunities and challenges for small-scale farmers. But the message was clear – the data does not exist to adequately understand what is happening locality by locality or country by country. There is a big gap in knowing who is on a pathway to greater prosperity and who is being left behind. Targeted and effective support strategies need to be based on a much more granular understanding of the livelihood strategies of diverse range of farming households and how their circumstances are changing. Investing in longitudinal, multi-sited, interdisciplinary research that can track livelihood trajectories over time and space and assess differential outcomes of various strategies and interventions will be essential if we are to fill those knowledge gaps.

Utilising digital potential. In all aspect of transforming small-scale farming digital solutions are seen as critical. This includes generating data, providing market information and access, payment systems, insurance, banking and finance, providing targeted social protection, and providing technical services. However, it must be stressed that these are not a panacea. They cannot replace, but only enhance other public and private services that are essential for creating and sustaining a vibrant rural economy.

Services to society. Rethinking the contribution of small-scale farmers. Instead of looking at the plight of small-scale farmers as a problem to be solved, what happens if we look at how small-scale farming can be part of the solution to a wider set of societal challenges? Four areas are key, providing a more nutrient-rich and diverse diet for society at large, providing eco-services that protect the environment, carbon sequestration through land use, and diversified and attractive rural livelihood options that help avoid large out-migrations (which put unmanageable pressures on urban areas and exacerbate the problems of cross-border migration).

Diversification – an underlying theme. Across the eDialogue series, diversification has become a common thread that has bound the panel discussion together. The diversity of farming households. The diversifying nature of household livelihoods. The need to diversify food production and marketing arrangements to meet nutritional needs. The diverse ways in which small-scale farming can contribute to society’s needs. And the need for a diverse yet integrated set of support measures to enable a socially just, environmentally sustainable, nutritionally smart and a resilient transformation of small-scale farming.

Acknowledgment. This blog draws on the views and perspectives offered by the eDialogue panellists (listed below) in the first fours sessions of the eDialogue and we thank them very much for their inputs and insights. The conclusions in this blog are those of the authors and may not necessarily be those of the panellists.

Panellists: Gilbert Houngbo, Jemimah Njuki, Milu Muyanga, Julio Berdegue, Avinash Kishore, Irene Annor Frempong, Theresa Ampadu-Boakye, Ajay Vir Jakhar, Kofi Takyi Asante, Regis Chikowo, Audax Rukonge, Hannington Odame, Steve Wiggins, Heitor Mancini Teixeira, Milena Umana, Claus Reiner, Maija Peltola, Alejandra Arce, Abdelbagi M Ismail, Aida Isinika, Martin T Muchero, Cyriaque Hakizimana, Adebayo Aromolaran, Aditi Mukherji, Sudha Narayana, Mekhala Krishnamurthy, Jeevika Weerahewa, Mamata Pradhan, Ranjitha Puskur, Grahame Dixie, Fabrizio Bresciani, Andrew Powell, Marlene Ramirez, Irish Baguilat, Tran Cong Than, Mario Herrero, Fábio Veras, Namukolo Covic, Felix Kwame Yeboah, Iris van der Velden, and Clara Colina.

Our first online session of this eDialogue began by “Setting the Scene” with a range of global and regional perspectives, and in the second session we heard more “Local Perspectives on Small-Scale Farming”, with a focus on sub-Saharan Africa. These vlogs are largely contributed by researchers, but a few farmers have shared their ideas and we’d love to hear from many more people so we encourage you to submit vlogs to us.

What we have heard to date only scratches the surface of the huge diversity of smallholder farming systems around the world. This is not surprising given that the best estimates are that there are more than 500 million small-scale farmers worldwide! Reflecting on what we have heard so far, what can we learn? For a start – small-scale farmers are key to both local and global food and nutrition security, and to rural livelihoods throughout the world. Second – generalisations are dangerous! All of us are influenced by our own experiences and examples. The huge diversity among what are termed small-scale farmers manifests itself not only in terms of differences among continents and regions, but also within countries and, the deeper we look, even within each village.

When thinking about the future of small-scale farming, we hear highly optimistic voices with some wonderful examples of individual farmers and farmer groups and cooperatives who are carving out their own future through farming. At the same time we recognise there are major challenges faced by small-scale farmers, not least due to the continual pressure to drive down food prices globally. We certainly don’t have all the answers so we’re counting on hearing many more voices and perspectives in the coming sessions.

Two critical questions come to mind for me, which I’d like to share and hear your comments on:

- We realise that simply tweaking the current systems is not enough – and we are challenged through the SDGs to think about “transformation”. To be honest I find this really hard – as a scientist I am pretty good at unpacking why things don’t work – but not great at imagining new futures. What would this transformation look like? I discuss this in an article just published which I entitled the “Food Security Conundrum of sub-Saharan Africa”. I’d love to hear your thoughts on what sort of policies and actions could support a transformation of small-scale farming on Africa.

- To what extent can successful models for rural development around small-scale agriculture in one part of the world be an inspiration for change and transformation elsewhere? It seems to me that the differences among continents – in terms of opportunities both within the agricultural sector, in terms of alternative employment beyond the farm, in terms of cultures and the general economy to name a few – are so different that we must be cautious in trying to transplant approaches from one place to another.

So there is plenty more to discuss – and in our next session we are planning a series of separate meetings for different regions to address some regional specificities. Then we will have a joint session to explore some of the similarities. This will hopefully provide guidance for our two sessions in November where we will think about transition pathways and then finally policies to support future transformations.

Please do join us! We need your input.

We’re pleased to release our report Farmers and food systems, what future for small-scale agriculture? (PDF: 10MB; opens in a new window)

Please note: the table in Box 1, page 13 was updated in August 2021 to reflect new information.

As we trundle through our supermarkets, or wander through an open market, looking for good deals we all to easily take for granted the food we purchase and the farmers who produce it. Most of what the world eats is produced by family farms and 90% of all farms are family run. These family farms vary from large commercial operations to tiny plots of land where producing enough to even feed the family is impossible.

With rapid urbanisation the pressure is on from consumers and governments for low food prices. The end result are low returns for most farmers, and most farm families are doing it tough.

It is critical to get our heads around the scale of the issue. Of the world’s approximately 560 million farms of <20 ha, 410 million or 72% are less than 1 ha, mostly in low- and middle-income countries. To make a living from 1 ha of land is not easy if not impossible. Yet, taking a family size of five, the livelihoods of over two billion people are linked to farms of <1ha. Taking all small-scale farms below 20ha and rural labourers this number gets closer to three billion or 40% of the world’s population.

While huge strides have been made in tackling poverty and hunger on a wider scale, the one to two billion people being left behind at the very bottom of the economic pyramid, often with very poor nutritional status, are predominantly rural people linked to agriculture.

The report puts this challenge in a wider context of changing food systems. That food systems, over the last half century, have met the huge increased demand for food has been an astonishing achievement. However, we now face the downsides as recognition grows about how unhealthy, environmentally unsustainable and inequitable many of the ways we produce, distribute and consume food have become.

A profound transformation is needed in how food systems function and in small-scale agriculture. Drawing on latest data, the report assesses the state of small-scale agriculture and the implications of structural changes in food systems for their future. It provides a set of conceptual framings that can help to unpack the complex issues around small-scale agriculture, highlight where more data and understanding is needed, and provides a reference point for debate.

Moving forward will require a much better country-level analysis of the structure of small-scale agriculture and rural poverty, coupled with long-term visions and strategies for transformation set within a wider food systems framework. Enhanced national level multi-stakeholder and cross-sector foresight and scenario processes, underpinned by better data, are needed to develop such visions and strategies. Ultimately, greater political commitment is required to bring about change. This calls for stronger and more influential coalitions for change, and greater public understanding and support.

Jim Woodhill

Saher Hasnain

Alison Griffith