By Bram Peters

Food systems are at a major transition point as accelerating forces like climate change, shifting shared realities, and growing uncertainties in global trade, AI, health, and the environment shape urgent questions, especially in Kenya, where concerns about the cost of living, democracy, and youth voices are rising.

These uncertainties were the focus of a two-day foresight and systems-thinking workshop at the Kenya School of Government in Nairobi, where 40 national and county-level stakeholders came together to explore the question: how can foresight be activated to catalyse Kenya’s food system transformation process?

The workshop focused on sharing experiences with using foresight for food systems change in Nakuru and Marsabit Counties and was facilitated by Foresight4Food, together with partners Results for Africa Institute, ILRI, University of Nairobi and Society for International Development. It sought to unpack the challenges and opportunities facing Kenya’s food system transformation process and identify key areas where foresight can reinforce connections across scales and build on key models that can help national transformation pathways.

Keynote Insights: From Crisis to Permacrisis

In her opening keynote, Dr. Katindi Sivi emphasized the need for anticipatory policy as Kenya is moving from crisis to polycrisis to permacrisis. Multiple shocks collide, including debt stress, climate change, food insecurity, youth unemployment, and technological disruption. She highlighted key challenges that affect food system governance:

- Fragmented ministries (e.g., agriculture, water, roads, lands, environment) work on different timelines, weakening coordination.

- Government structures are too linear, slow, and siloed to handle interconnected risks.

- Policies often address yesterday’s problems instead of emerging ones.

Foresight provides a framework to: identify weak signals early, prepare for a range of plausible futures, build resilience into public institutions, improve policy coherence across sectors and ensure stewardship for future generations.

This is an urgent challenge, and it must be a priority, especially for public civil servants tasked with guiding governance. This message was echoed by Professor Nura Mohamed, Director General of the Kenya School of Government, who emphasized the critical need to invest in strategic foresight for driving public service reform in Kenya. He also pointed out the need to move from a tendency to ‘celebrate the intention’ to actually implementing the policy frameworks that exist.

The Role of Foresight in Governance

A closer look at process challenges shows that all stakeholders have a role to play, with counties offering important lessons. Key issues needing urgent attention include:

- Policy frameworks are strong but poorly coordinated: Counties like Nakuru and Marsabit use solid planning tools, but overlapping mandates and fragmentation slow progress.

- Blended finance works but must be locally grounded: Nakuru’s County Revolving Fund shows potential, offering affordable loans in partnership with local banks.

- Stakeholder ecosystems are rich but underused: Many actors—from county departments to universities, NGOs, and development partners—need clearer role mapping to reduce duplication and boost collaboration.

- Public participation is essential: Marsabit’s grassroots processes—ward-level engagement and community-led budgeting—strengthen legitimacy and local ownership.

- The research-to-action gap persists: Research often remains unused; living labs, innovation hubs, and university incubation centres are key to translating evidence into practice.

The Kabazi Foresight Innovation Model

A core discussion revolved around the opportunity to learn from the Kabazi Foresight Innovation Model, which has now been piloted in Nakuru and Marsabit throughout the FoSTr programme. Kabazi Ward Innovation Model shows how local food systems stakeholders and communities can work at Kenya county level to offer a locally rooted decision-support ecosystem. This model integrates systems thinking and foresight approaches with a multi-stakeholder partnership approach energised by community leadership. Named after the Kabazi ward in Nakuru, the central idea is to empower and leverage pre-existing Beyond 2030 Networks. These comprise ward departments, chiefs’ forums, school heads, women’s groups, local businesses, and community actors as the foundation for co-creation and systemic change towards a better food system future. This model can be replicated in any county in Kenya.

Workshop Recommendations for Food System Transformation

At the end of the workshop, participants agreed the following:

- Continue to strengthen and build a networked community of practice, integrating foresight, food systems change and facilitation to support Kenya’s food system transformation process

- Strengthen capacity building and communication materials on systems thinking and foresight, especially with the Kenya School of Government and key learning institutes

- Consolidate and scale the county-level ‘Kabazi Foresight Innovation Model’ to share experiences with other counties and support decentralised governance

- Invest in local learning ecosystems such as Community Research and Living labs to support locally embedded and applied sustainable innovation and farmer-centric learning

- Support legislators to adopt a futures perspective when it comes to laws and regulations, such as through the Senate Futures Caucus

- Work towards societal mindset shifts, behaviour change and accountability mentality. The participants noted that value cultivation is crucial for long-term change: values such as responsibility and awareness of food systems must be cultivated, while addressing entrenched social norms that stop us from reframing power and relations within the current food system

Voices of Change: The Power of Spoken Word

The session was enlivened by the spoken word performances of Dorphanage, who artfully captured the deep urgency for change but also reminded participants of the deeply political nature of food systems transformation.

Governments speak of empowerment

While selling futures to foreign hands

Signing away tomorrow for the comfort of today

Pretending not to see the blight they sow

Africa does not lack muscle or mind

Only the will to honor its own abundance

Our fields are fertile with potential

But the plow is steered by self-preserving hands

By Bram Peters

These days, the world is a turbulent place, posing challenges for all food systems stakeholders – and headaches for policymakers. Policy makers, tasked with key responsibilities in governance decisions and policy formulation and implementation, are faced with complex, interconnected and dynamic issues amid political sensitivity and ambiguity. How to be a 21st-century policy maker in the Arab region and in Jordan, when reacting is not enough, and transformation is the goal?

Foresight and Systems Thinking

In the face of these challenges, systems thinking and foresight are emerging as key approaches shaping anticipatory governance and participatory policy design. Embraced by institutions such as the European Union, OECD, and UN system, as well as by leading countries like Singapore, Finland, and the United Kingdom, systemic practice and foresight offer powerful perspectives and options for decision-makers. Today, foresight stands as a discipline that combines data, systems thinking, and stakeholder engagement to strengthen resilience, adaptability, and strategic preparedness in an increasingly uncertain world.

Foresight Workshop

In Amman, 27-29 October 2025, Jordan’s Ministry of Agriculture and Ministry of Planning and International Cooperation hosted an interactive high-level capacity workshop: “Foresight for Systemic Policy-Making”.

Foresight4Food, in collaboration with the National Alliance against Hunger and Malnutrition (NAJMAH) and the Arab Organisation for Agricultural Development (AOAD), facilitated the workshop based on experience supporting Jordan’s food systems transformation process. Over the past three years, the FoSTr Programme, supported by the Government of the Kingdom of the Netherlands through IFAD, in collaboration with the Higher Food Security Council (HFSC) in Jordan, has been working to develop foresight and scenario-building capacities as part of the country’s food system transformation process.

Engagement from the Government

Representatives from more than ten ministries came together – from Education and Finance to Energy, Water, Industry, Transport, Crisis Management and beyond — to explore how foresight and scenario thinking can be used to improve policy making in turbulent and uncertain times. In collaboration with the Arab Network for Agricultural Development, the event also welcomed representatives from Tunisia, Sudan, Lebanon, Somalia, and Yemen – adding valuable regional insights.

The success of the foresight work on food systems sparked interest from other ministries and led to this workshop on how foresight could support integrated policy making across government. Participants explored the future of employment, energy, water, and migration, recognising how these challenges intertwine. Insights emerging included the realisation that, to navigate the future, such collaboration across government is not just helpful — it’s essential. The representatives from other countries enriched the discussions with their experiences and brought a regional perspective while taking home valuable lessons from Jordan.

Participant Recommendations

Participants concluded the workshop by offering 11 recommendations to the Higher Council for Food Security and the Ministry of Planning. These recommendations included, among others, the following key messages:

- It is recommended that ministries and other public institutions integrate foresight and anticipatory approaches into their planning, policy formulation, and decision-support processes.

- National planning authorities or their equivalents should take the lead in identifying and harmonizing common drivers, assumptions and trends.

- The participants recommended organizing a Training of Trainers (ToT) workshop for participants from Jordan and other Arab countries.

- The participants called for the establishment of a national Jordan foresight network, enabling more national capacity building, coordination and regional collaboration.

By Jim Woodhill and Bram Peters

We’re excited to launch our new guide: “Using Foresight for Food Systems Transformation – A Guide for Policymakers, Practitioners, and Researchers.” Developed collaboratively by the UN Food Systems Coordination Hub and Foresight4Food, this guide is being released today to coincide with the UN Food Systems Summit +4 Stocktake (UNFSS+4), taking place in Addis Ababa, Ethiopia, from July 27 to 29.

Why This Guide Matters

Transforming food systems to ensure better health, greater equity, and environmental resilience demands future thinking. We must collectively envision how our food systems can evolve—and confront the risks of “business as usual.” Anticipating future shocks and stresses can help drive proactive policy, investment, and innovation before crises hit.

This guide is a hands-on resource for applying foresight and scenario analysis at national and local levels to accelerate food systems transformation. It demystifies the basics of foresight, lays out practical steps for launching a foresight process, and offers real-world examples and curated resources.

What You’ll Find in the Guide

- Clear explanations of foresight and scenario analysis methods

- Step-by-step guidance for facilitating participatory foresight processes

- Insights and tools drawn from the global Foresight4Food network

- Case examples illustrating how foresight is being used in diverse contexts

At the heart of this approach is bringing together diverse stakeholders—from farmers and consumers to policymakers and private sector actors—to build shared understanding, trust, and momentum for collective action.

Part of a Broader Set of Resources

This new guide complements the Foresight4Food “Foresight for Food Systems Change Process Guide & Toolkit”, which dives deeper into participatory tools and techniques for systems mapping and scenario building.

It also aligns with new resources like FAO’s “Transforming Food and Agriculture through a Systems Approach”, which supports systems thinking for transformation. In parallel, Alliance Biodiversity and CIAT are highlighting the importance of subnational stakeholder engagement as a critical entry point for change.

A Call to Action

Transforming food systems will require significant investment—but more importantly, it needs broad-based commitment. Consumers, producers, businesses, and political leaders must be aligned on the necessary changes and the trade-offs involved. That means shifting mindsets, creating political will, forging new alliances, and rebalancing power.

As we move beyond the UNFSS+4, we need renewed focus on investing in high-quality, inclusive stakeholder processes. The foresight approach outlined in our new guide offers a powerful pathway to doing just that.

By Bram Peters, Food Systems Programme Facilitator

The future is a mystery, full of uncertainties, risks and opportunities. Yet, humans and human systems have a remarkable ability to turn imagination into reality. In this landscape of uncertainty, foresight becomes an essential tool, helping us navigate what lies in the future. This is especially important when it comes to food systems transformation.

In this blog, I will endeavour to give you a glimpse at how foresight, awareness of the political nature of futures, and alternative scenarios can help us rethink and reshape our food systems for a more just and sustainable future.

Four Ways to Think About the Future

According to Muiderman et al. (2020), there are four main approaches to foresight:

- Assessing Probable (and Improbable) Futures

Example: The IPCC climate scenarios, which predict likely outcomes based on different climatic and environmental trends, and possible climate actions. - Contending with Multiple Plausible Futures

Example: Scenario matrices that explore what could happen in different situations under various combinations of uncertainties. - Imagining Diverse, Pluralistic Futures

Example: Visioning exercises where we picture a desired future, then work backwards (backcasting) to figure out how to get there. - Scrutinizing the Performative Power of Future Imaginaries

This approach examines how our collective visions of the future can actually shape reality.

Most foresight work focuses on the first three approaches. But in today’s world, shaped by pandemics, global conflicts, and rising political tensions, having the skills to apply the fourth approach can be considered to be more important than ever. A recent Synthesis Review of food system futures conducted by Foresight4Food identified that we can generally see various clusters of key food systems futures around ‘business as usual’, ‘global sustainability’,

‘local solutions’, ‘rising inequalities’, and ‘uncontrolled chaos’. However, it was also observed that none of these described scenarios portray very radically different food system futures.

The Power of Collective Imagination

Jasanoff and Kim, in their book Dreamscapes of Modernity (2015), introduce the idea of socio-technical imaginaries:

“Collectively imagined forms of social life and social order reflected in the design and fulfilment of nation-specific scientific and/or technological projects.”

In simpler terms, societies tell themselves stories about who they are, where they’ve been, and where they’re going. These stories—these imaginaries— can reshape history, redefine the present, and chart a course for the future. And often, they serve the interests of those in power.

The Future Is Political—and It’s Already Here

Why does this matter? Because the future isn’t just something that happens to us. It’s something that societies seek to actively shape, often through powerful narratives. Consider some current, concerning, imaginaries being promoted by powerful elites:

- Trump’s “Golden Dome” and the slogan “Make America Great Again”

- Elon Musk and other tech company elites’ visions of Artificial General Intelligence

Alternative imaginaries to counter power and transform societies toward a very different future also exist. Think about:

- The Degrowth Manifesto, as proposed by Kohei Saito in his book ‘Slow Down’

- Ministry of the Future, as narrated by Kim Stanley Robinson

Shaping Better Futures—Together

Foresight, when used critically, inclusively and deliberatively, has the power to shape more inclusive and constructive imaginaries. Jasanoff writes that these imaginaries “offers a glimpse into the realities of the known, the made, the remembered, and the desired worlds in which we live—and which we have the power to refashion through our creative, collective imaginings.”

In other words, we can—and should— together imagine alternative, inclusive, sustainable and transformative futures, making them tangible. The time to do this, at scale, is now. The Foresight4Food Global Workshop, taking place in Jordan from 15-19 June, will include an exercise on ‘Radical Food System Futures’. This will harness the collective intelligence of the foresight and food systems community, and enhance focus on imagining very different food systems than we see around us today.

By Bram Peters

The future of food systems is uncertain, yet one thing is clear—transformative change is urgently needed. Climate change, inequality, and geopolitical instability are reshaping how food is produced, distributed, and consumed. How can we navigate these complexities and create a more sustainable, resilient food system?

At the Power of Foresight Workshop held on 30-31 January 2025 at the FAO headquarters in Rome, experts and practitioners gathered to discuss how foresight can drive food systems transformation. Their insights reveal a crucial truth: the process itself— working with complexity, embracing inclusivity, diverse perspectives, and collective intelligence—is central to making real progress.

Insights from the ‘Power of Foresight’ Workshop

- 17 different cases and the stories of 48 participants from 27 countries demonstrated that foresight approaches have much to offer to the process of food systems transformation

- Working with complex systems is what it’s about, and effective foresight practices for food systems change to embrace this

- Openness to new and inclusive perspectives should be central to all foresight for food systems transformation efforts

- The process brings the answer – and foresight can bring awareness of crucial process elements such as collective intelligence, agency, time and scale

- Embracing the ‘ifs’: how you do foresight, and what comes before and after, is just as important as the development of scenarios

- Foresight is not one approach or one methodology – there are a diversity of ways to go about it

- The national food systems pathways can benefit from foresight approaches

Photos: 30 January 2025, Foresight4Food workshop. FAO Headquarters, Rome. Photo credit: ©️FAO/Cristiano Minichiello

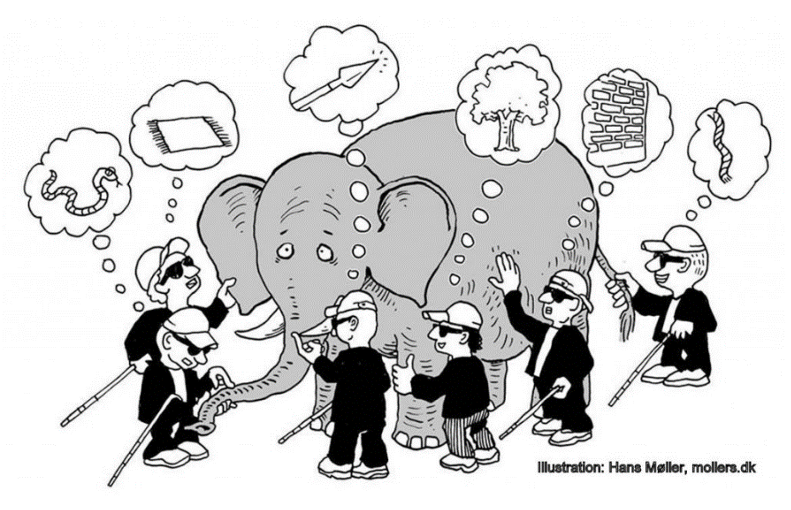

Working with complex systems: Let’s talk about the elephants in the room

When it comes to food systems transformation, there isn’t just one elephant in the room—there are many. These metaphorical elephants represent the complex, interconnected challenges we face, and ignoring them only hinders progress.

- First, as a whole range of interrelated challenges and assumptions we are not working on enough: whether that’s climate change, human rights, global geopolitical turbulence, growing inequality. All these challenges together form a context of global polycrisis.

- Second, we can see elephants in the room related to our apparent inability to take decisive transformative action in food systems: a lot of talk, limited action.

- Finally, we can see elephants as representing systems. An elephant can represent a dynamic, complex food system, of which we might only be able to see or understand the trunk, tusks, ears or tail.

Like the elephant and the blind men metaphor (see image to the right), food systems are deeply interconnected with global issues like climate change, inequality, and geopolitical instability. Tackling these requires a holistic approach, recognizing that transformation cannot happen in silos.

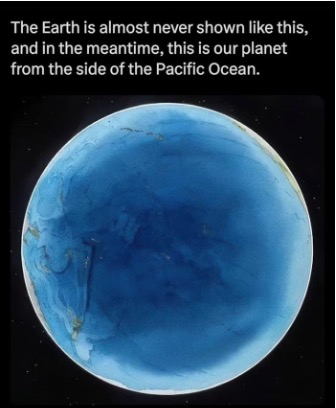

Gather new and inclusive perspectives – and change your own

What’s central to talking about complex food systems is perspective. We all have different mental images of food systems—whether local agriculture, marine ecosystems, or trade networks. Expanding our perspectives helps identify new entry points for addressing issues like malnutrition, poverty, and sustainability.

For some, like from the Pacific region, it’s about marine ecosystems in which food is central. Changing your perspective can be a helpful way of looking at a complex topic: such as to see the Pacific food system composed not of ‘small island states’ but rather ‘large ocean states’ connected with the global food system through trade, governance, and oceanic currents. Why is flipping your perspective so important? It helps to reframe entry points for discussion with other stakeholders and view the root causes of things like malnutrition, non-communicable diseases, poverty and human rights abuse in food systems differently.

If you are able to change your perspective, it helps to understand the viewpoints of those less heard. Having an inclusive process to gather different viewpoints is crucial to changing perspectives and behaviour, mobilising for collective action and creating shared visions of the future.

The process is the answer

Ever tried herding cats? Well, transforming food systems is about fostering C.A.T.S.—a process centred on:

- Collective intelligence – Multi-stakeholder collaboration and co-creation

- Agency – Empowering change through action

- Time – Bridging past, present, and future

- Scale – Recognizing interconnections between local and global systems

So, what does it mean to herd cats when talking about food systems? It means there are no magic bullets: the process is central to the outcome.

Effort on addressing the ‘ifs’

Foresight can be of great added value to support the food systems transformation process. Whether it is about co-creating alternative futures, conducting backcasting towards a more desirable scenario, highlighting the cost of delayed action, or informing anticipatory policy – foresight and scenario tools are a key toolbox in the hands of systems change champions.

In order for foresight to be effective, there are a number of conditional ‘ifs’ i.e., if foresight experts and facilitators:

- Are able to move beyond added value, tackling pre-conditions, obstacles, and constraints affecting how stakeholders prepare for the future.

- Not only preach to the converted – we need to involve stakeholders who think and act differently

- Are cognizant of power differences, lock-ins and political economy

- Build on other approaches that also provide value, such as design thinking, human-centred development and mission-oriented policy making.

- Pay attention to what comes before and after the development of scenarios

Scenarios only developed from the perspective of single organisations or without meaningful consultation and dialogue will not be effective.

Foresight approaches and national food systems pathways

There are a broad range of foresight approaches, some expert-driven or participatory, others quantitative, experiential, creative or analytical. Each has their value – but these needs come from a clear user need and scope within a food system. However, it is essential to keep in mind that foresight is a tool, not a panacea, and cannot address all questions.

With 156 national convenors driving progress through implementing 137 national food systems transformation pathways, the upcoming UNFSS+4 Stocktaking Moment (July, Addis Ababa) presents an opportunity to share lessons and strengthen impact. What we have seen the past two days in Rome, is the incredible richness and diversity of initiatives that use foresight to support the food systems transformation process.

Sharing the lessons from these initiatives, communicating the potential of foresight, and supporting the national convenors to further realise the impact on transforming food systems outcomes will be crucial in the run-up to the Stocktaking Moment.

By Bram Peters

The Foresight4Food FoSTr team has just returned from an active and productive trip to Kenya, despite the challenging political situation in the country. From our perspective, this highlights the need to adapt to turbulence and to use foresight to build resilience for Kenya’s food system.

From June 19 to 26, together with my team members including Jim Woodhill, Herman Brouwer, and Wangeci Gitata-Kiriga we conducted a range of food systems foresight workshops in Nairobi and Nakuru with a wide range of national food systems stakeholders. Here is a brief update on the action.

Navigating turbulence

On the morning of June 19, Foresight4Food, together with partners ILRI–CGIAR, Results for Africa Initiative and University of Nairobi, organised two sessions in Nairobi. The interactive breakfast session was all about ‘Navigating agri-business in turbulent futures’. The session was co-hosted by IFAD Kenya and was attended by a range of private sector associations, business support services, innovation facilitators and impact investors.

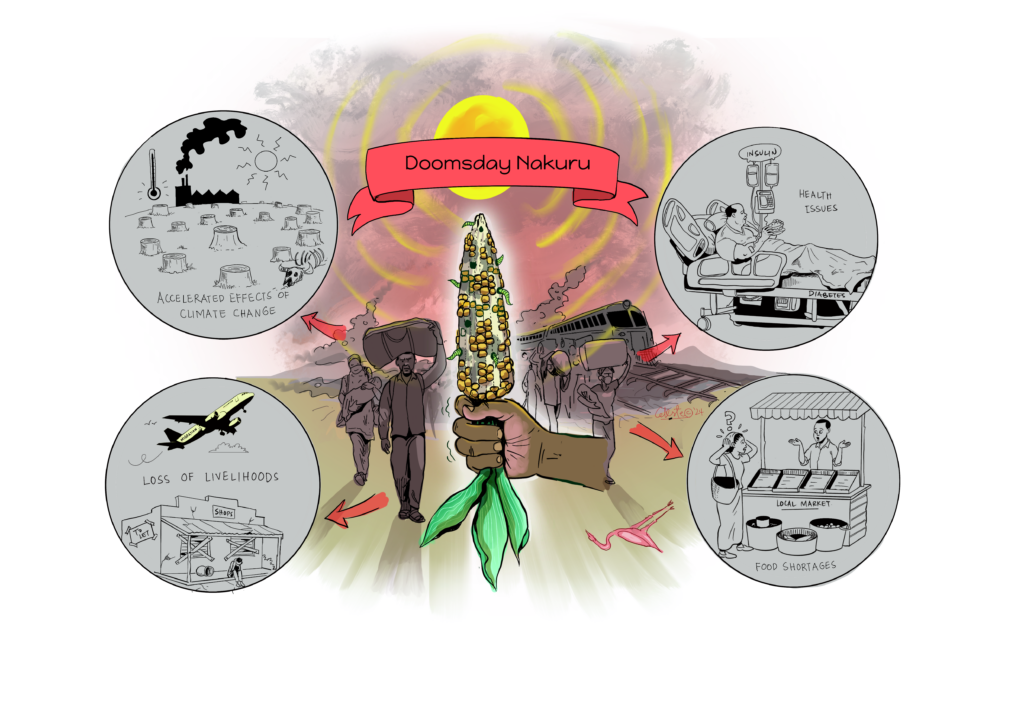

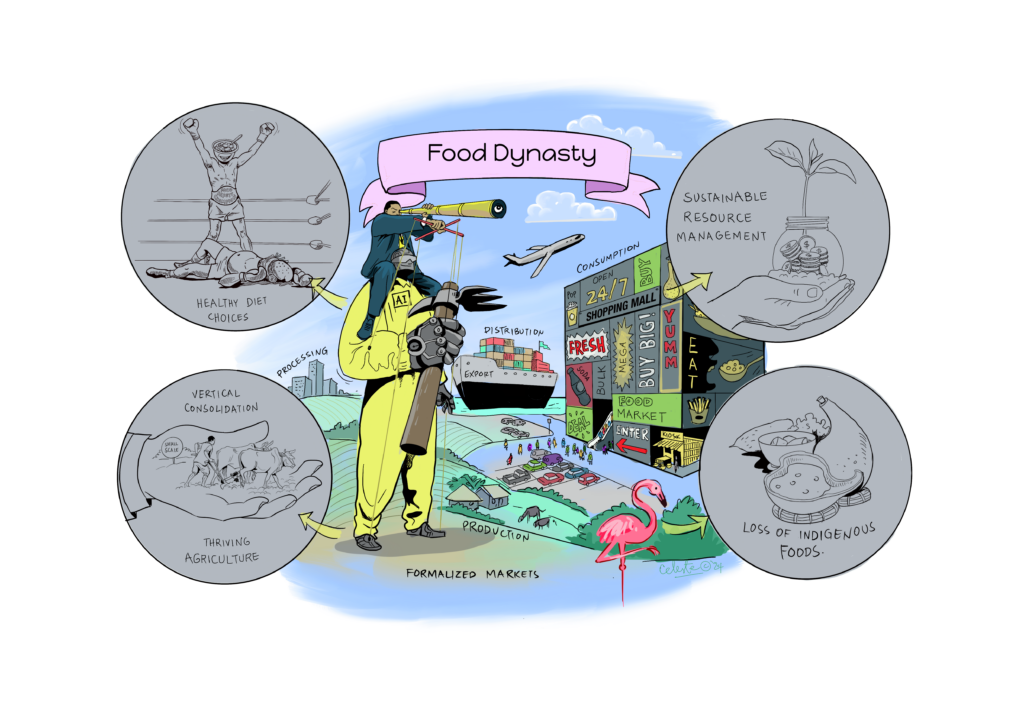

The focus of the meeting was to introduce the topic of foresight in relation to agribusiness in Kenya, share some of the scenarios that were developed in the context of Nakuru, and discuss the implications of different futures of the food system. Participants were shown five different scenarios of how the food system might look in 2040 in Nakuru and were invited to think through and discuss the implications of these scenarios.

With a strong presence and involvement of leaders from various private sector associations such as the Agriculture Sector Network (ASNET) of the Kenya Private Sector Alliance, the discussion invited stakeholders to reflect not only on trends and uncertainties emerging in Kenya, but also how their own businesses are preparing for the future.

Supporting the pathways for food system transformation

In the afternoon of June 19, the FoSTr team organised a national update session on the progress of FoSTr since June 2023. The session was attended by many individuals from the morning session, as well as representatives from government, civil society and research organisations. The FoSTr team presented the latest updates, including the launch of a ‘Kenya Food Systems Mapping Report’, and with a collection of scenarios for the Nakuru food system.

With a special presentation by the Ministry of Agriculture and the Food Systems Technical Working Group and special remarks from IFAD on the 3FS tool, it was discussed how a wide range of ecosystem support initiatives are buttressing the national food systems transformation pathways in Kenya. The approach by Foresight4Food to engage with two counties, Nakuru and Marsabit, and to build on Bottom-up initiatives showed how our approach complements the ongoing national-level initiatives.

Systemic Theory of Change

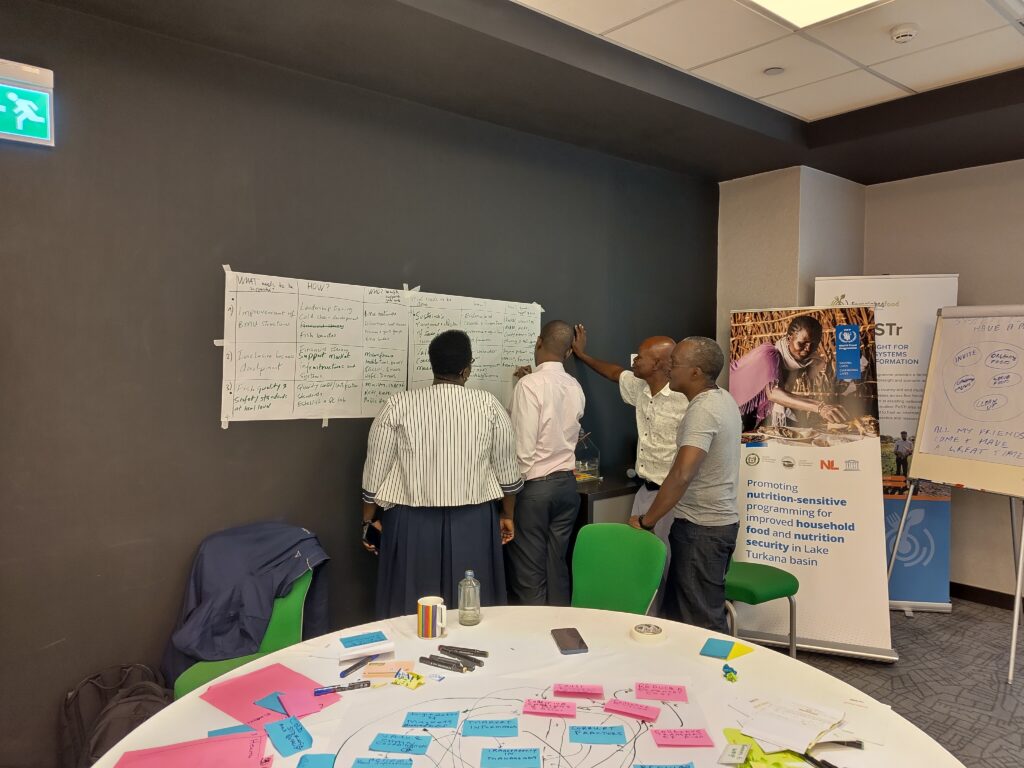

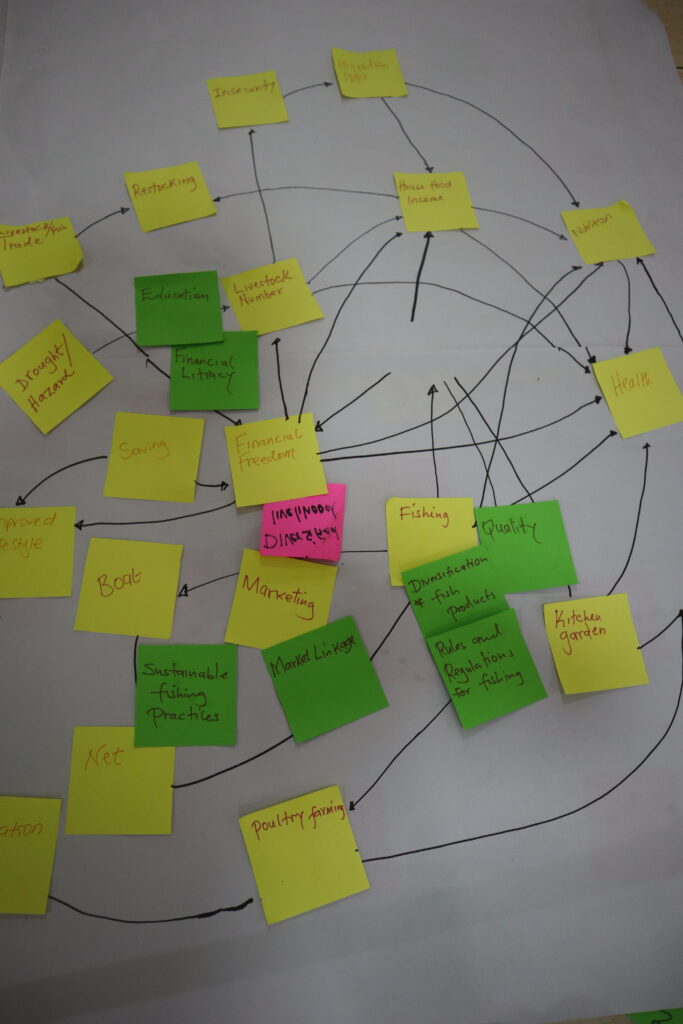

From June 19 to 21, the Foresight4Food FoSTr team facilitated a 3-day workshop for the inception phase of the new Netherlands-funded, World Food Programme and UNESCO on ‘Sustainably Unlocking the Potential of Lake Turkana. Stakeholder representatives from the Lake Turkana region (both on the Marsabit and Turkana sides of the lake) gathered in Nairobi to engage in a shared analysis of the complex food system and co-create the high-level focus of the programme.

The Turkana Lake food system is highly complex, with high food insecurity, vulnerability to climate change and conflict, and many cultural dynamics around pastoralist and fisheries livelihoods. Finding market opportunities and strengthening resilience is not easy, and requires a different way of working. Using the Foresight4Food approach, and building on 6 scenarios that were developed in previous workshops in Marsabit and Turkana, stakeholders explored what might need to be done to understand systemic risks and how lasting opportunities can be triggered.

Preparing a Systemic ToC is all about analysing the context, articulating the transformations needed in light of various future scenarios, and developing the building blocks for action. The building blocks include pathways, processes and partnerships. Through many interactive discussions and exercises, the stakeholders conducted value chain mapping of the fish value chain, CATWOVE for articulating systemic change narratives, and Causal Loop Mapping.

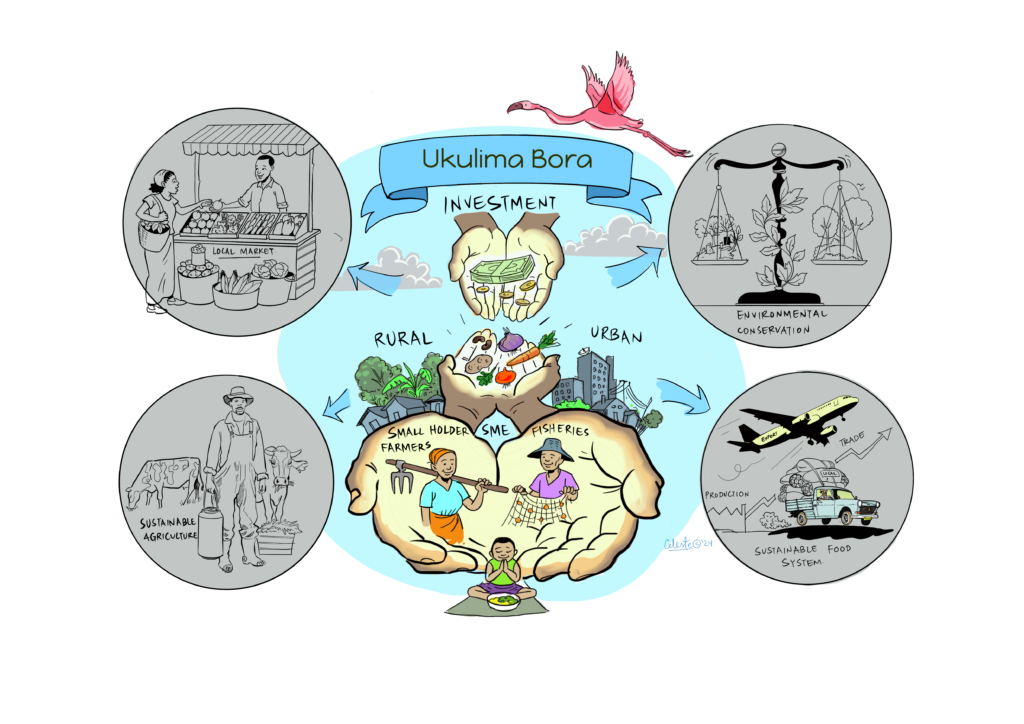

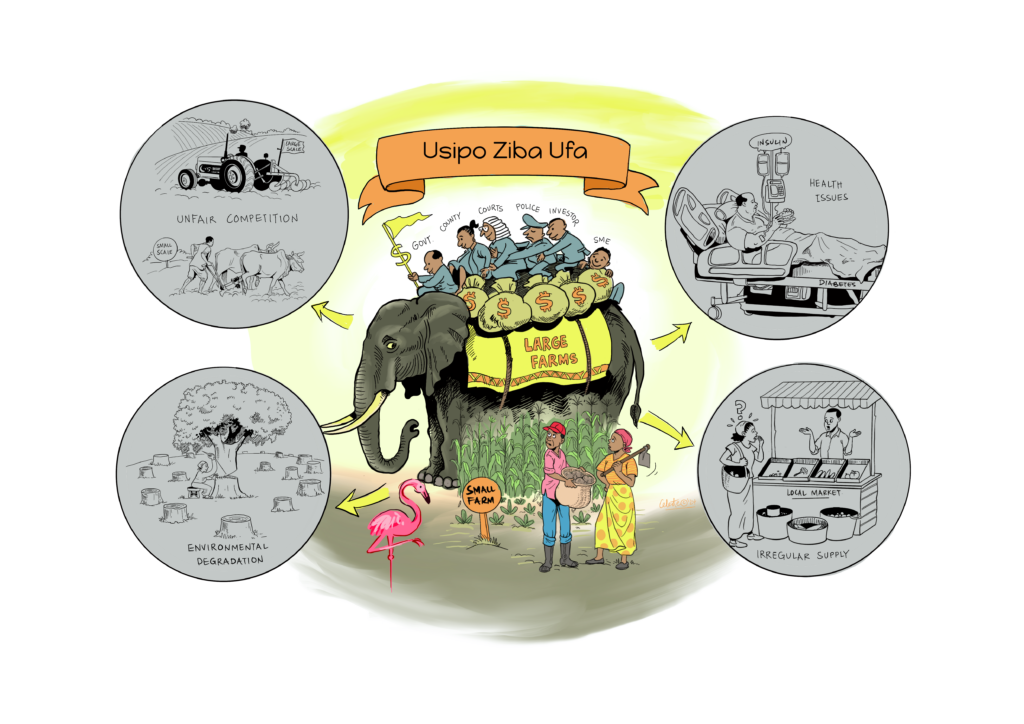

Manifesto for Change for the Nakuru Food System

On June 24 and 25, the FoSTr team including partners ILRI-CGIAR, Results for Africa Initiative and University of Nairobi once again visited Nakuru, now to explore systemic change pathways. As we already noted from previous workshops, the food system of Nakuru County is full of potential, as Nakuru’s natural resources are rich and a wide range of agricultural value chains are represented. However, challenges related to food and nutrition security and environmental sustainability exist. Trends of climate change, unhealthy diets and land fragmentation are appearing. The future holds many uncertainties. In order to future-proof the food system, it is urgent that investments are made to further enhance the resilience and sustainability of food and agriculture in Nakuru.

Since November 2023, a diverse group of more than 40 different stakeholders from Nakuru county have been coming together to consider the future of food system, supported by researchers and facilitators of Foresight4Food. This inclusive group looked at the challenges and opportunities for food and agriculture today and how they might evolve in 10-15 years. Food system analysis, an assessment of drivers and trends relevant to Nakuru, and 5 scenarios were developed by this group.

During these two days, stakeholders from Nakuru engaged in scenario interpretation and Causal Loop diagramming to come up with key pathways to kickstart food system transformation in Nakuru. These outputs culminated in a Manifesto for Change: a vision for the desired future for Nakuru’s food system and a range of possible pathways that can set us in that direction, while preparing us for a range of uncertainties. The Manifesto calls upon all stakeholders to join and align their actions, and intensify collaboration to transform Nakuru’s food system so that it can feed its people nutritiously; advance economic development; restore balance with nature; grow in-county revenue and eventually GDP growth for Kenya.

by Bram Peters

As a part of the FoSTr programme, the Foresight4Food team organized the “Exploring Alternative Futures for Jordan’s Food System” workshop in Amman, Jordan that brought together food systems stakeholders in Amman to discuss the future of Jordan’s food security. Here are some of the observations and insights from the event.

With themes of resilience, adaptation, action, and collaboration, participants engaged in scenario planning and back-casting exercises to anticipate challenges and shape future outcomes. Key uncertainties like water availability, healthy diets, regional trade, and business structures were explored through four scenarios set in 2040. These insights, supported by quantitative modeling, fostered rich discussions about desirable futures and the actions needed today to create a sustainable, resilient food system for Jordan.

During the workshop, colleagues from the University of Jordan and Jordan University of Science and Technology presented four policy briefs. These were: Food Loss and Waste, Water-to-Food Conversion, State of Smallholder Farming in Jordan and Malnutrition. Each policy brief captures the state of knowledge and offers recommendations to explore how to address these issues from a food systems perspective.

The FoSTr team introduced four critical uncertainties that will be highly important and uncertain to the long-term future of the Jordan food system:

- The extent of fresh water available to agriculture

- The extent to which healthy diets are adopted

- Level of ease of regional trade

- The type of business structure the food system will have

Each of these uncertainties was combined to offer four scenarios, taking place in 2040, up for discussion with the participants. Supported by insights from quantitative simulation modelling, the implications on food systems outcomes were explored in each scenario. Some scenarios described that the people of Jordan adopt healthy diets despite a challenging regional trade situation. In others, severe limitations on fresh water for agriculture were seen in combination with a highly corporate-led food system.

Additionally, the participants explored how that situation might look in each. These scenarios served to open up minds towards the possibility of different situations emerging in the future and highlight the need for anticipatory action and systemic change.

The scenarios led to a discussion of what might be the ‘most likely‘ and ‘most desirable’ scenarios for the Jordan food systems stakeholders. The outline of a desirable future, informed by trends and uncertainties, was formulated to serve as a guiding star. A back-casting approach was used to then explore what events and turning points might occur between 2040 and now to realise that desired future. Based on this timeline, stakeholders brainstormed a range of different actions and stakeholders which are needed now, to already start pushing the system towards the Desired Future.

Building on the encouraging shared co-ownership of the results of the workshop, the Foresight4Food FoSTr team will continue efforts to develop policy briefs, deepen the action areas that were developed, and support the Food Security Council of Jordan in proving the underpinnings for the ongoing work on national food systems transformation.

By Bram Peters – Food Systems Programme Facilitator, Foresight4Food

In the north of Kenya, on the border with Ethiopia, the landscape is expansive and dry. Pastoralism is the main source of livelihood, but to the west of this landscape is Lake Turkana, one of the largest saline desert lakes of the world. Here communities engage, some productively and others reluctantly and out of desperation, in fishing.

In March 2024, the Foresight4Food FoSTr team traveled to the fascinating Kenyan county of Marsabit to facilitate a multi-stakeholder forum to support the co-creation of the new ‘Sustainably Unlocking the Economic Potential of Lake Turkana’ programme.

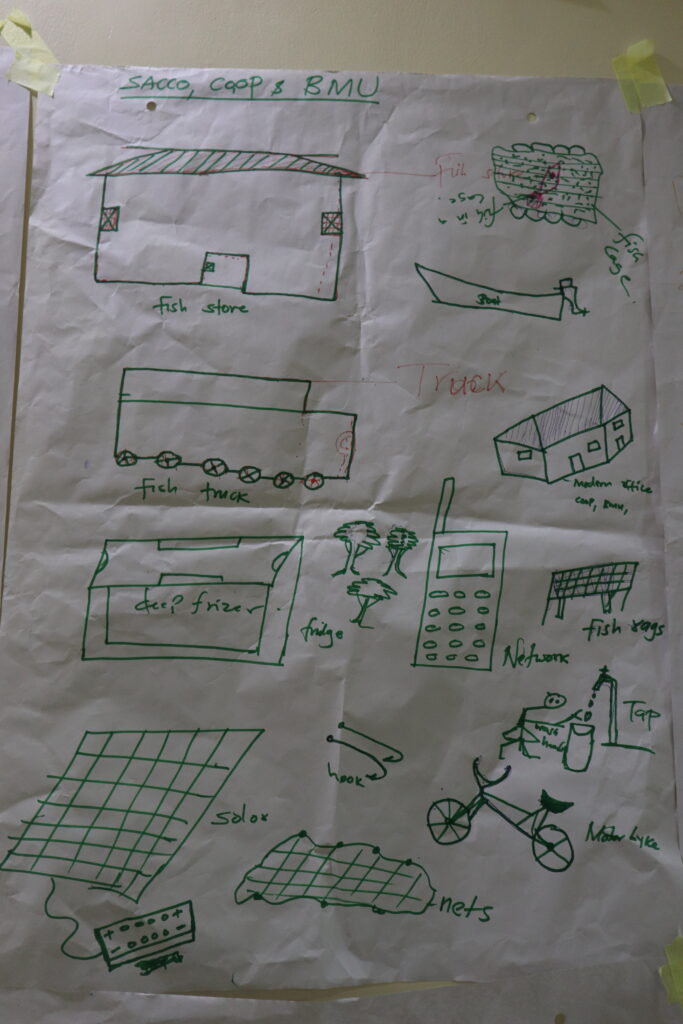

In Marsabit, stakeholders from around the Turkana Lake, including fishers, traders, service providers, county government technical officers, and non-governmental organizations, came together to analyze the context and co-create future scenarios and intervention areas for a new WFP and UNESCO programme, funded by the Embassy of the Kingdom of the Netherlands.

Together with the World Food Programme and the World Food Programme Innovation team, the FoSTr team held a highly interactive and productive three-day workshop. As most stakeholders mainly spoke Kiswahili, we switched to short presentations with much emphasis on interactive group work. On the first day, the workshop focused on contextual understanding of the Lake Turkana food system as well as the Marsabit county livelihoods, using the Rich Picture mapping exercise. Participants together drew the food system, the geography of the lake, but also the stakeholders, activities, key relations and dynamics.

On the second day, the groups presented their deep knowledge of the context to each other and elaborated on this. Workshop participants tackled key trends shaping the food and livelihoods system: groups discussed how various themes (for example: lake water levels, fish stocks to income sources, conflict, and education) changed over time and what they expect to happen 10 years into the future. Important in this discussion is their analysis of what driving issues would influence change in the future.

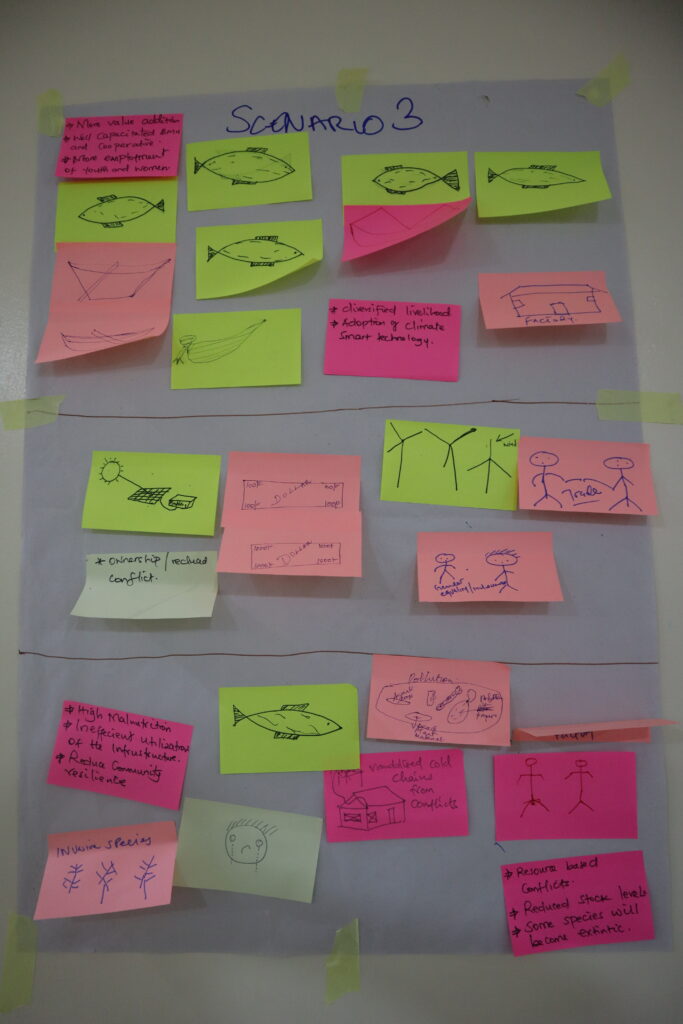

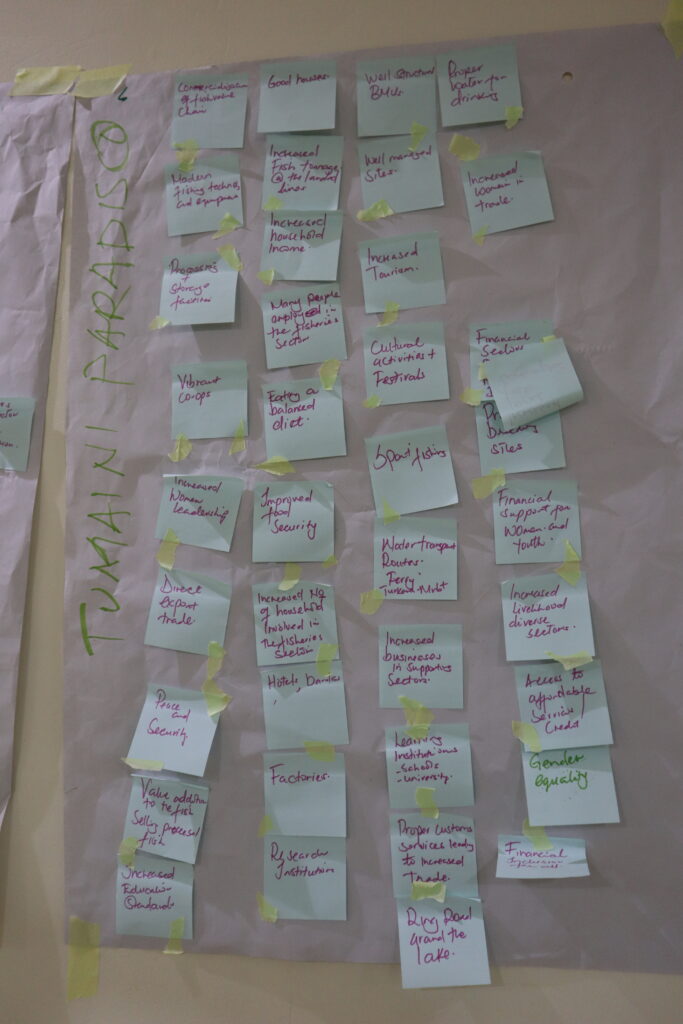

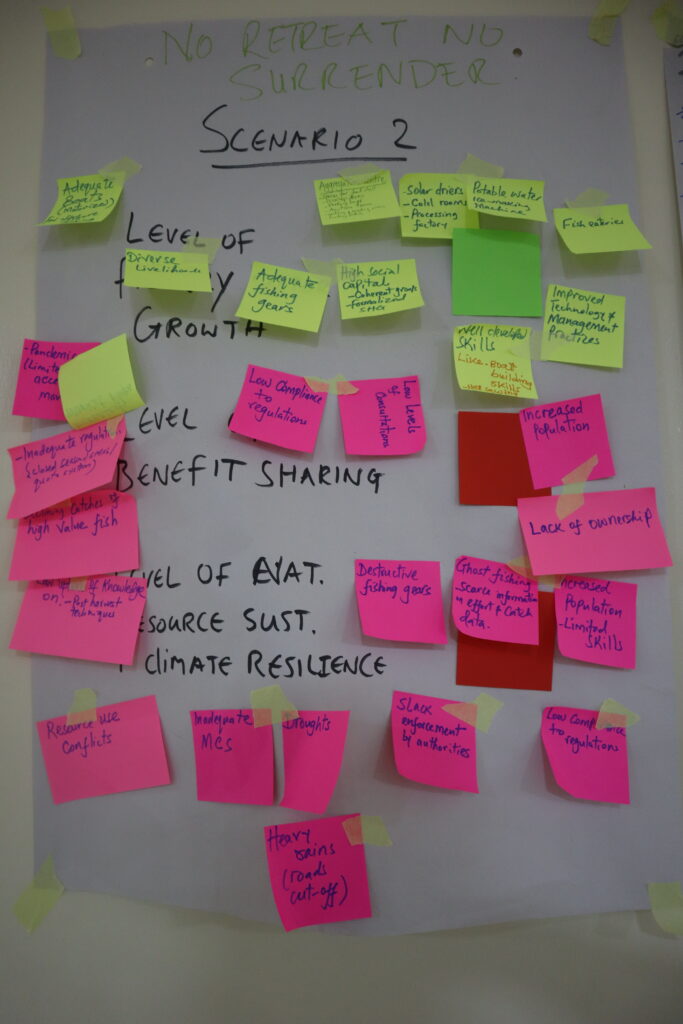

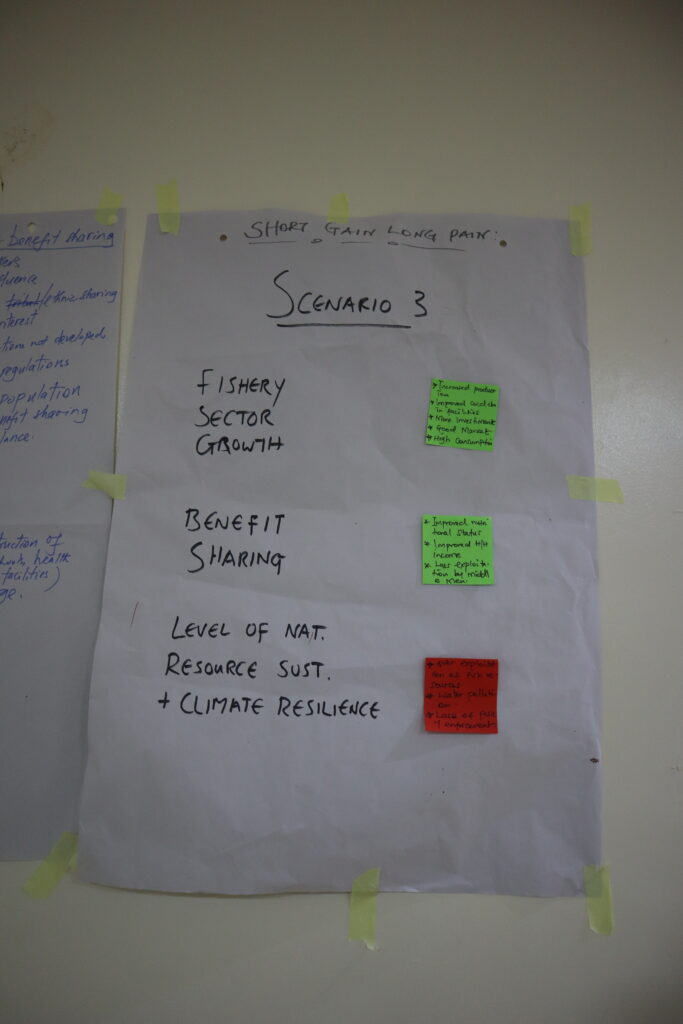

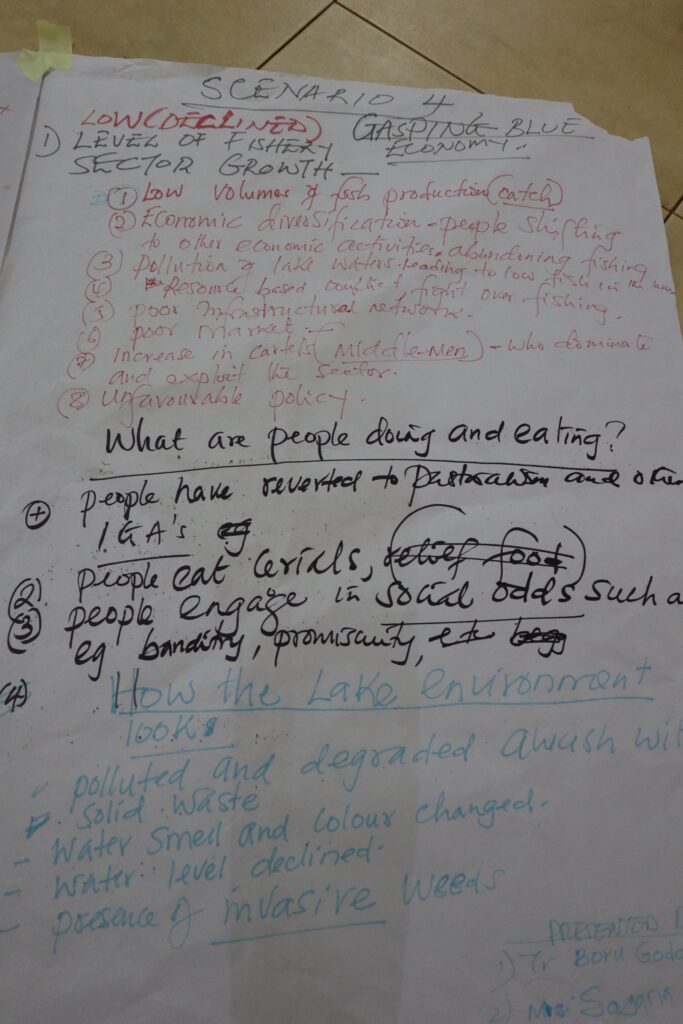

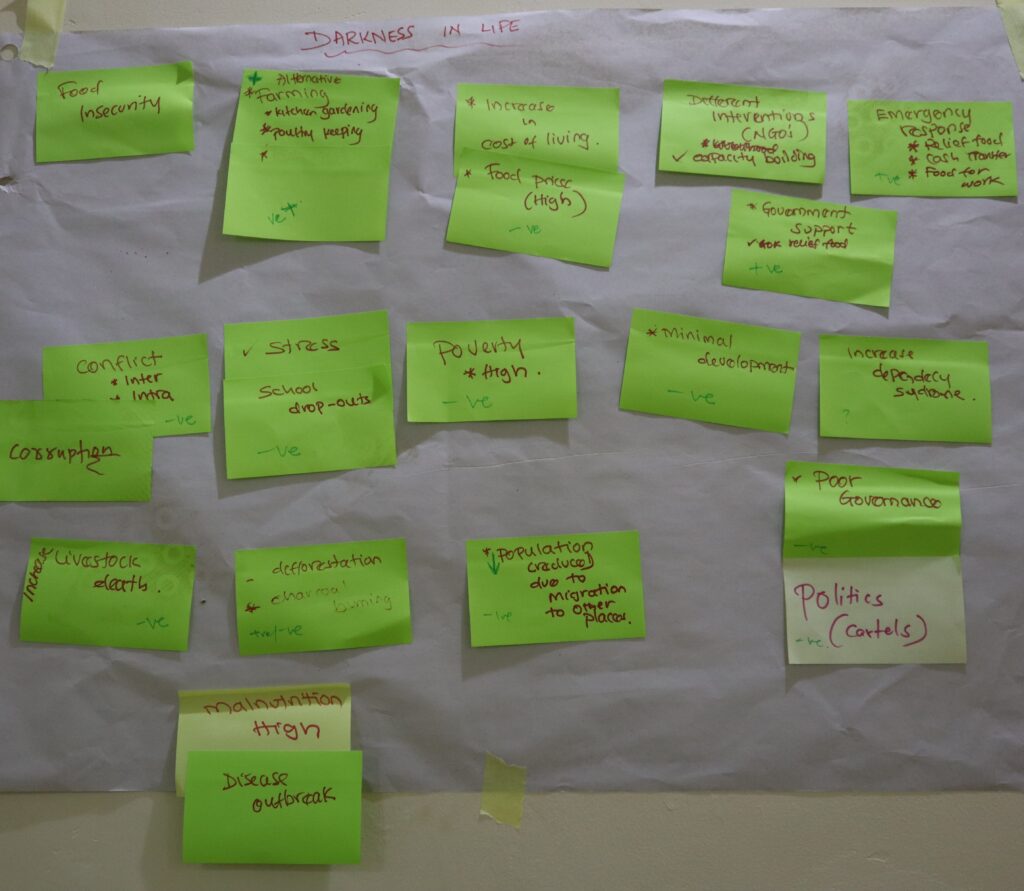

5 scenarios were created for the future regarding the fisheries sector and supporting livelihoods, as well as an in-depth discussion on key entry points for intervention in the system. These scenarios had names that described these futures succinctly:

- ‘Tumaini Paradiso’, a future with a growing fishing sector, inclusive benefit sharing and sustainable natural resource management;

- ‘No retreat, no surrender’, a situation in which the benefits of a growing fisheries sector are controlled by a few;

- ‘Short gain, long pain’, a scenario where the fisheries sector grows and livelihoods improve around the lake, but the environment is not maintained;

- ‘Gasping blue economy but others rise’, is a future where the fisheries sector remains marginal for communities, but other sectors are developed that also contribute to inclusive development and environmental sustainability

- ‘Darkness in life’, a bleak outlook where none of the envisioned sustainable economic development around the lake delivers and where climate resilience is low, and conflict is rife.

Different stakeholders participating in the workshop had different opinions on the likelihood of certain scenarios emerging. Some imagined the situation worsening, while a few viewed the future more positively. These reflections clearly showed a combination of outlook of participants as well as the signals they interpret from the current situation and the trends seen now. Interestingly, none of the stakeholders felt the ‘Paradiso’ scenario was likely, showing that the programme needs to be modest in its systemic ambitions, but also be ready to do things very differently. These scenarios showed what could become a very relevant frame of reference to the stakeholders as well as the programme implementors.

On the last day of the workshop, participants explored a common vision for the future, and how the food system is currently working. This led stakeholders to have a first try at exploring what is needed to change that system toward the common vision.

At the end of the workshop, I felt highly positive about these fruitful discussions that enabled participants to think about what might happen to the Marsabit food system in the years to come, and what factors would influence these changes. In addition to that, the insights gathered through the multi-stakeholder forum are expected to not only support the inception phase of the programme but will also support multi-stakeholder engagement throughout the programme.

The Foresight4Food FoSTr team will continue to support the World Food Programme team in realizing the ‘Sustainably Unlocking the Economic Potential of Lake Turkana’ programme inception phase. A follow-up workshop will take place in Turkana County from March 25 to 28, with stakeholders from that side of Lake Turkana.

by Bram Peters

The UN Food System Summit +2 StockTakingMoment is behind us. It was attended by more than 155 National Food Systems Convenors were in place and 107 countries shared their national food system transformation pathways accounts. 3300 participants, including delegations from 182 countries, 21 world leaders, and 126 ministers (particularly from the Global South) joined.

What highlights and insights remain from the 3-day event in Rome? Joining on behalf of Foresight4Food, I felt it was a mixed bag, with both positives and negatives. Below are some insights, facts, backdrop, and other observations:

First off, a few facts were shared which really hit home:

According to Amina Mohammed, Deputy Secretary General of the UN, we are in the worst possible shape to reach the SDGs. Almost all indicators are lagging behind.

- 2.4 billion people across the globe, mostly women and people in rural areas, did not have consistent access to nutritious, safe, and sufficient food in 2022 (according to the latest SOFI report 2023).

- The world is not on track to reach the SDGs: only 15% of the 140 targets are on track since the 2015 baseline. Close to half of the targets are moderately or severely off-track.

- To achieve the Zero Hunger goal by 2030, IFAD stated that an additional $400 billion investment, per year in food systems is required, meaning efforts must be doubled in half the time. For reference: not doing anything would cost $12 trillion.

- It is projected that, by 2050, 70% of people will live in cities. At the same time, in those areas, consumption of processed and convenience food is increasing, with impacts on obesity, diabetes and other non-communicable diseases.

Some geopolitical and climate change-related dynamics in the backdrop:

- Southern Europe has experienced a heatwave of unprecedented levels, with high temperatures and wildfires from Rhodes to Spain. In Rome, temperatures have peaked at 41.8 degrees Celsius in recent weeks.

- The Russia-Ukraine war and Russia’s intention to withdraw from the Black Sea Grain Deal (BSGD) and a forum with African leaders was to be held in Saint-Petersburg after the summit. According to IFPRI, under the BSGI, about “65% of wheat was exported to developing countries. This includes 725,167 tons of wheat exported through the World Food Programme to help relieve hunger in Afghanistan, Djibouti, Ethiopia, Kenya, Somalia, Sudan, and Yemen. By contrast, about 83% of maize exports under the BSGI have gone to developed countries and China” (IFPRI, July 2023). This comes in the wake of a report that indicated that majority of the Black Sea Grain Deal production was consumed in Europe and used for animal feed.

- Italian host, Prime Minister Meloni, opened the summit, referencing the positive nutritional aspects of the ‘Mediterranean’ diet, but also had just a week earlier co-led the signing of a controversial migration pact between the EU and Tunisia. This was alluded to in her welcoming speech, where she urged for further investment especially in Africa so that jobs are created on the continent and sought in Europe.

- Ethiopian Prime Minister Abiy Ahmed was one of the speakers at the Opening Ceremony. Ethiopia and her northern neighbours are still negotiating on the planned dam along the Nile, which would directly affect food systems in Egypt and Sudan—no mention of cross-border resource sharing in his remarks.

Key takeaways:

- Food systems knowledge has deepened and capacities on food systems approaches have generally grown. This includes how countries use this but also the application within various Rome-based agencies. Now it will need to be seen whether coordination on such a diverse range of issues can improve and whether implementation increases pace. A hint of this integration was seen in the fact that clear links are made to the upcoming SDG conference and the COP28.

- Urgency is recognized as high, which made it very relevant to hold this UNFSS+2 StockTake to maintain momentum. Having a visible and active participation of high-level political representatives showed widespread commitment. However, the lack of substantial presence from Northern countries with commitments to their own national transformations was a missed opportunity.

- ‘Transformation’ was spoken about often, but the sense of real transformation ongoing is not apparent yet. A few insightful examples: the discussion on true pricing of food, a study in Andhra-Pradesh where agro-ecological farm production empirically demonstrated equal economic earning and better social and environmental benefits compared to conventional farming approaches; and the example by Switzerland on the establishment of a citizens’ assembly to offer recommendations for Switzerland’s food policy to break their parliamentary deadlock surrounding agricultural policy (something the Netherlands can learn from?).

- A side event about livestock was interesting with debate about the contribution that the sector has regarding GHG emissions, livelihoods, nutritious food, and what was being done in different parts of the globe.

- It was heartening to hear the enthusiasm in the stories of the national convenors, the driving forces for coordination and collaboration at national levels. However, it was also seen that many countries do not yet have strong institutional mechanisms in place to support cross-sectoral decision-making.

- A lot of important topics were addressed, including multi-stakeholder collaboration; inclusion; school meals; food security in (poly)crises; budgeting and financing for national Action Plans; policy alignment across sectors; and climate resilience. Multiple leaders from South America and EU mentioned agro-ecology. Some topics I missed included tackling unfair international trade agreements and improving global food trade governance (as referenced here in a (Dutch) long read by colleague Bart de Steenhuijsen Piters from WUR).

- Foresight approaches appeared highly relevant, as stakeholders shared the need to scan horizons for upcoming trends; build resilience for anticipatory approaches (WFP shared an example from Niger where less food aid was needed due to improved resilience approaches); and include ‘lived’ (indigenous) interpretations of past and future- alongside scientific evidence- in our transition pathways.

- Accountability did not receive much attention. With the exception of special events on the first day of the UNFSS on measuring and bench-marking, there was relatively little accountability of progress toward promises made at the 2021 Summit. It will be very important, at a next StockTake, to get more metrics and data of countries on their national transformation pathways progress.

Other observations:

- The UN agencies were pleased to see the high-level turnout, especially from the South. Private sector, youth, and indigenous groups were represented in smaller numbers but made active contributions.

- Engagement from member countries, the private sector, civil society as well as the scientific community seemed less than before.

- Limited (or less visible?) participation of Europe and the USA. Whether this is a sign of decreased interest, or because there were fewer planned preparations for UNFSS+2 compared to UNFSS, is yet to be seen.

- (only) A few countries from the global North reported on their own food systems pathways and challenges instead of reporting on their ODA-funded food system support to partners in the global South.

- A counter-summit was organised, raising issues of lack of inclusion and corporate-led influence.

- Quite a few UN Agencies are investing and learning about foresight. For example, the Future of Food and Agriculture publication (FOFA DDT) was presented at a side event. Also, the newly reinvigorated FAO Office of Innovation is actively interested in foresight methods and eager to exchange with Foresight4Food.

- A nice photo exhibition was held in the main atrium, called ‘Food Futures’, funded by the European Commission Joint Research Centre, with the objective to explain food systems and realising that cultural shifts are needed to transform these.

Side-event on multi-stakeholder collaboration

At the Stock Take Moment, Foresight4Food was able to contribute to a side event called ‘Multi-stakeholder collaboration for food systems transformation: From concepts to Action ‘. This side event (see here the recording), organised together with UNDP, UNEP, FAO, Global Alliance for Improved Nutrition (GAIN) and Netherlands Food Partnership focused on the need to bring people together to bring change. How to ensure inclusion, tackle power differences, and create a shared language to help with the national pathways? There is such a diversity of food system stakeholders. In a diverse panel with representatives from Vietnam, South Sudan, Nigeria, Switzerland, and Kenya, the question asked was: ‘How’ do we do a multi-stakeholder collaboration?

Key experiences shared included how the Vietnamese government went down to the local level to collect insights, conveners who actively consulted the grassroots level in South Sudan, iterative rounds of consultations at different levels and regions in Nigeria, and how a citizen’s assembly was established in Switzerland to advise on food systems.

Wangeci Gitata-Kiriga, representing Foresight4Food Initiative, shared how in Kenya, Foresight4Food combines a participatory process with an evidence-based understanding of the current food system and the possible future of the food system. Using participatory visual approaches such as Rich Picturing, stakeholders exchange perspectives, talk openly about power, and start developing a shared language on uncertainties and possible futures of the food system.

The session concluded with the observation that we need to understand ‘transformation’ better, that this requires a huge effort, and needs inclusiveness and diversity. We have a broad range of tools at our disposal that we can use. It is also not about the powerful vs the powerless, but rather also about breaking barriers, creating and maintaining an equal playing field, and involving the unexpected and unusual players.

See the website NFP Connects of the Netherlands Food Partnership for a more detailed summary.

Reflections on the Third Global Foresight4Food Workshop in Montpellier 2023

By Bram Peters, Food Systems Programme Facilitator

Strike? What strike?

Amid the turbulence created by strikes in France, a diverse and committed group of people still managed to get to and from the Third Global Foresight4Food Workshop in Montpellier from 7-9 March.

Perhaps, as foresight practitioners, we should have seen it coming! You would think that foresight practitioners who make it their business to look into the future might be better at anticipating turbulence, or at least a substantial level of social upheaval.

Why go through the trouble to come anyway? Because food systems are in turbulence as well. Never has there been a more urgent need to transform food systems. More than 3.1 billion people globally do not have access to healthy diets. The impact of climate change in the form of droughts and disasters is increasing. Agri-food systems are responsible for one-third of greenhouse gas emissions. The Covid-19 pandemic and the Russia war in Ukraine have shown how integrated, yet fragile, the global food system is.

We need foresight in food systems transformation

Yet, “the greatest danger in times of turbulence is not the turbulence; it is to act with yesterday’s logic” (according to futurist Peter Drucker). That’s where foresight comes in.

We need a long-term perspective to explore alternative pathways to reach desirable or avoid undesirable food system changes.

Following from the UN Food Systems Summit in 2021, many countries are searching for ways to navigate change and develop anticipatory policy to guide them.

As such, the issue on the table was: how can the foresight community of practice offer support and relevant advice to food system stakeholders?

Creating a safe space to think, connect and engage

In Montpellier, Foresight4Food brought together a diverse group of foresight practitioners, researchers, users of foresight and implementors of food systems approaches to discuss how foresight can contribute to national level food systems transformation pathways amid all this turbulence.

The Masterclass on the 7th generated a lot of energy, a shared language, and many practical explorations of tools and methods. The main Workshop on the 8th and 9th saw interactive exchanges, presentations of valuable projects and sharing of insights.

Among others, organisations such as FAO, CGIAR, GFAR and CIRAD shared ground-breaking applications of foresight thinking linked to food systems. There were cases from Asia, Africa; thematic cases on food systems data; new and past initiatives; dashboards and multi-stakeholder processes.

Researchers and data experts, such as from Wageningen University and Food and Land Use Coalition, shared innovative tools and models to advance new ways of projecting trends.

Critical perspectives were shared. Insights were brought from Africa and Asia, such as by Forum for Agricultural Research in Africa, and much more.

Moving the needle: developing our forward agenda

We, as Foresight4Food team, gained a lot of energy and motivation to continue fostering this vibrant network.

A few pickings of things we want explore moving forward. Develop and encourage ‘Communities of Practices’ through active partnership principles. Make a meta-analysis of existing food system foresight cases and comparative insights and lessons. Create guidance for foresight community on the process of actually doing foresight for food systems. Develop key principles for quality approaches and a toolbox to support implementation.

Thankfully, even in the face of the French strikes, a quality characteristic among foresight practitioners is the ability to be adaptable and flexible – as is needed when you work with the complexity of food systems.

FAO’s new insightful scenarios for the future of food systems

By Bram Peters, Foresight4Food Global Facilitator

What drivers can trigger food systems transformation? How can we move beyond business as usual in the face of rising food insecurity, environmental degradation and economic instability? The good news is that we can shape food systems to be more resilient and sustainable. The challenge: trading off short-term benefits in search of longer-term outcomes. FAO developed four future scenarios that explore that explore these questions and how we can navigate such paths.

End of 2022, the United Nations Food and Agriculture Organisation (FAO) published the report ‘The Future of Food and Agriculture – Drivers and triggers for transformation’. The key triggers and drivers for transformation are identified based on a diverse and wide range of literature and expert knowledge and then applied to four scenarios to achieve the FAO goal of ‘Four Betters’: better production, better nutrition, better environment and better life. Trade-offs over time and the key use of policy triggers are at the centre of the report’s conclusions. This blog dives into these drivers and futures, and delves into the key implications of this report.

In Search of ‘Four Betters’

FAO strives for ‘Four Betters’: better production, better nutrition, better environment and better life. How to achieve such a vision, and how will this look in the future?Much depends on how drivers play out, how stakeholders tackle trade-offs, and how certain triggers are turned into policy options and implemented. The recent report makes clear that the historical development paths followed by high-income countries, drawing from hegemonic power, colonial wealth and unsustainable practices, are impossible for current low- and middle-income countries to follow. This requires a mindset shift regarding taking responsibility, sharing burdens and investing in a new type of focus on the long-term objective.

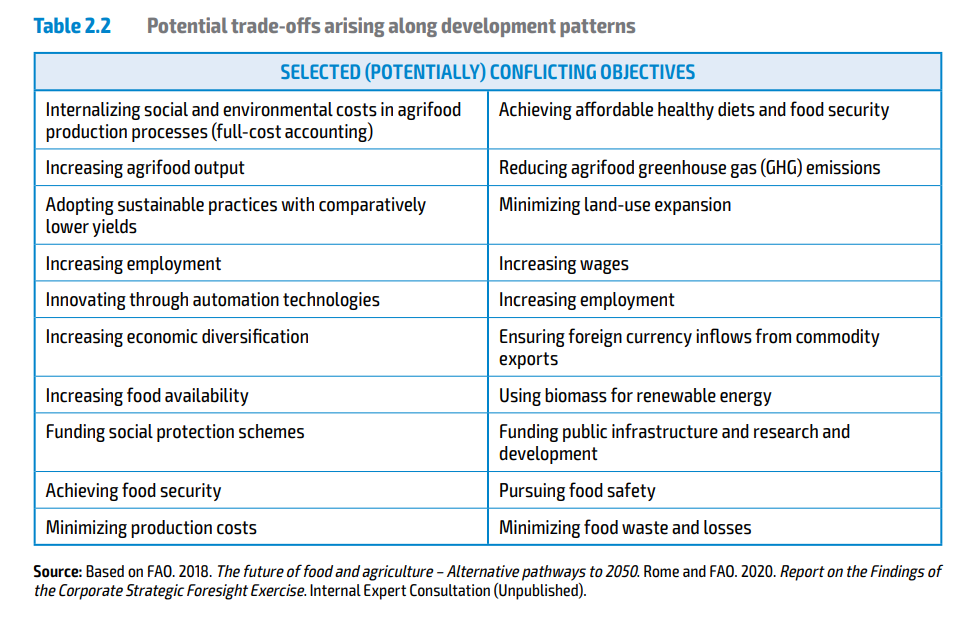

Difficult-to-navigate trade-offs and choices include:

- Short-term productivity gains against greater sustainability and reduced climate impact; “Better production starts from better, critical and informed consumption, but producing more with less will also be unavoidable”.

- Efficiency against inclusiveness; for instance, “technological innovations are part of the solution – provided new technologies and approaches are also accessible to the more vulnerable”.

- Short-term economic growth and well-being against greater long-term resilience and sustainability. In concrete terms, this means “selling the message that well-off people have to lose out economically in the short run, in order to reap environmental benefits and resilience for all in the medium and long term is counterintuitive in this short-termism era”.

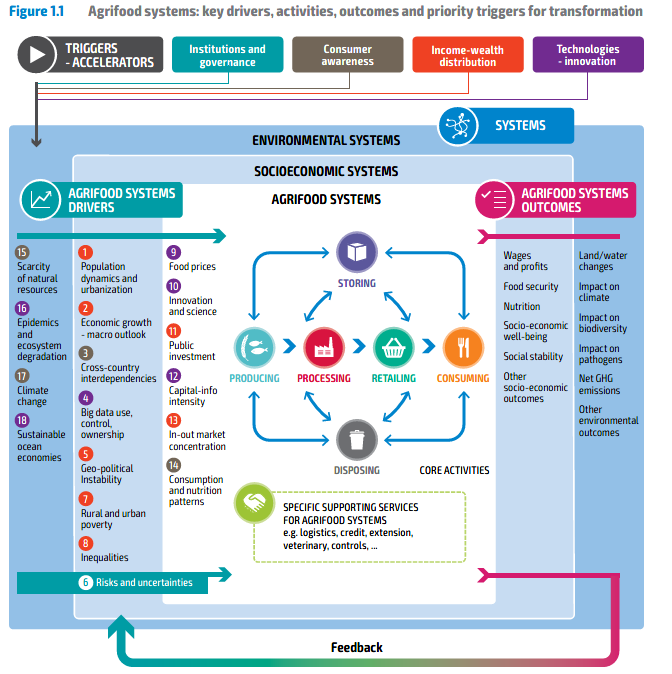

These are difficult but essential messages. The report highlights the importance of realising that food systems transformation is an inherently political and cultural process. Promising drivers and triggers for change are occurring globally, but must be harnessed and adapted. Let’s have a look at some of the drivers identified. Drivers are categorised as ‘overarching, systemic drivers’, which often include global, geopolitical and demographic elements, ‘drivers affecting food access and livelihoods’, and ‘drivers that affect food and agricultural production and distribution processes. Drivers within these categories affect agri-food, socioeconomic and environmental systems (Figure 1.1).

Captured in an agri-food system framework (partially based on previous work from Foresight4Food), some predominant drivers include scarcity of natural resources, epidemics and ecosystem degradation, cross-country interdependencies, inequalities, big data use and control, geopolitical instability, food prices, public investment and consumption and nutrition patterns. Cutting through these drivers are ‘risks and uncertainties’, as many drivers can turn into hazards, risks and cascading crises.

New Future Scenario Narratives

Radically divergent futures can emerge if the interactions of drivers, changes in individual and collective behaviour, the materialization of natural events, risks and uncertainties, and the influence of public strategies and policies play out differently. FAO developed four scenarios from the near future to the end of the century and explored the implications of each for food systems. The FAO ‘Four Betters’ were used to formulate four visions and narratives of the future. Using a ‘back-casting approach’ (where a number of aspirational visions are developed and it is then explored what future pathways could lead to these futures). The FAO team explored how each of these futures could be reached through combinations of key drivers, interconnections between agri-food, socioeconomic and environmental systems and ‘weak signals’ of possible futures.

By imagining alternative pathways and priority trigger points, the four scenarios are not defined as separate destinations to get to by moving along four different train tracks. Instead, each future

scenario could be reached at different points depending on the strategic policies and decisions implemented, the trade-offs in policymaking, and unless irreversible processes are triggered.

Trade-offs now and in the future will offer wicked dilemmas for decision-makers. Foresight thinking highlights that certain current decisions may lead to short term results but can increase medium and long-term uncertainty and, in the worst situations, foreclose certain long-term futures. See various conflicting policy objectives in Table 2.2.

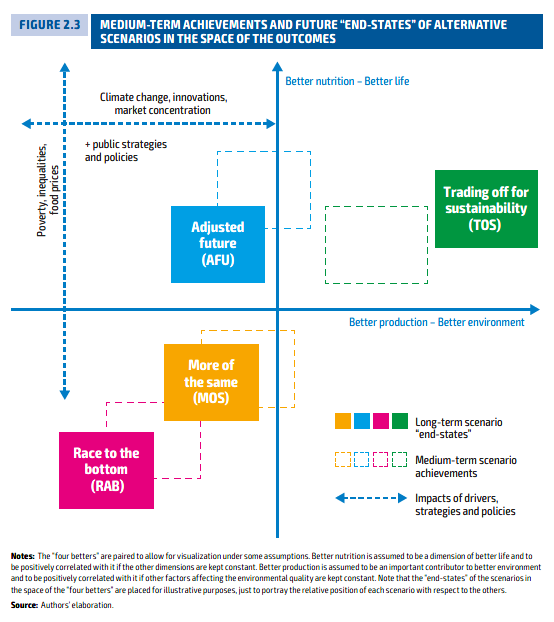

The four scenarios are visualised on a juxtaposition of 2 paired FAO ‘Betters’: ‘Better nutrition/Better life’; and ‘Better production/Better environment’. These betters were paired to enable visualisation and relative positioning of futures vis-à-vis each other in a matrix.

The four scenarios include:

1. More of the Same (MOS)

2. Adjusted Future (AFU)

3. Race to the Bottom (RAB)

4. Trading off for Sustainability (TOS)

More of the Same involves muddling through reactions to events and crises while doing just enough to avoid systemic collapse, which will lead to the degradation of agri-food systems’ sustainability and to poor living conditions for many, increasing the long-run likelihood of systemic failures. Adjusted Future entails that some moves towards sustainable agri-food systems will be triggered in an attempt to achieve Agenda 2030 goals. Some improvements in terms of well-being will be obtained, but the lack of overall sustainability and systemic resilience will hamper their maintenance in the long run.

Race to the Bottom is characterised by gravely ill-incentivized decisions that will lead to the collapse of substantial parts of socioeconomic, environmental and agri-food systems, with costly and almost irreversible consequences for a vast number of people and ecosystems. Trading off for Sustainability would mean that awareness, education, social commitment, sense of responsibility, participation and critical thinking will trigger new power relationships and shift the development paradigm in most countries. Short-term gross domestic product (GDP) growth will be traded off for the inclusiveness, resilience and sustainability of agri-food, socioeconomic and environmental systems.

Each scenario narrative explores how certain key domains could develop. What would geopolitics, economic growth, demographics, resources and climate, agriculture, and technology and investment in food systems look like in each future? How each key driver would materialise in each future is also illustrated. For instance, the driver ‘Innovation and Science’, in the MOS scenario, imagines that various agricultural technologies such as robotics, blockchain and AI were developed and were expected to support data-driven transformation but failed in the face of too much focus on means and not enough institutional and social innovation. In the AFU scenario, some investments in novel technologies helped improve productivity and resource use efficiency.

However, more systemic approaches such as agroecology and multi-cropping were not followed through and unequal investment across countries took place, meaning that real transformation was incomplete. In the RAB scenario, science was further used to ensure control of corporate entities or geopolitical allegiance, reinforcing inequalities and further exclusion of small-scale actors and leading to faster exhaustion of natural resources. Finally, in the TOS scenario, science and innovation are fully geared toward sustainable food systems and involve strong contributions from educated and aware civil societies using innovative decision-making processes. Greater awareness of consumers facilitated the trade-off of outputs with sustainability and supported the creation of a diverse and resilient agri-food system across communities.

Various assumptions always play a role in developing scenarios and their policy triggers. Compared to previous scenario exercises, a key assumption, due to updated data models and prognoses, is that the collapse of substantial parts of agri-food, socioeconomic and environmental systems is almost certain(!). A second important assumption in the TOS and RAB scenarios is that ‘globally emerging well-educated, informed, critical, increasingly aware and non-manipulable civil societies’ are a crucial factor that either can enable or prevent those futures from being realised. Another assumption is that governance of markets is important to address inequalities. This is contrary to scenarios developed by the World Economic Forum, where the assumption was that if markets are connected and economic growth is fast, inequalities will also decrease.

So, what does it mean to work with these futures?

Concluding most directly: the picture is not reassuring, but something can be done if with urgency. SDG achievement is off track, finding ‘win-win’ solutions is difficult if not impossible, and MOS and RAB scenarios must be avoided with great urgency as they could very well become reality. However, the implications of the scenarios and the complexity of food systems also mean that other lessons require deeper reflection. Two elements are essential to underline: the interconnectedness of systems and our abilities to boost transformative change.

The interconnectedness of systems means that negative trajectories and global challenges can cascade into even bigger crises. Solutions cannot emerge easily due to entangled problems within agri-food, socioeconomic and environmental systems. Climate change, shock resilience, sustainable resource use, poverty and ending hunger are at the top of overarching challenges.

Agency grants us the means to set a new path, but it may be challenging to implement change under the influence of drivers and opposing power and interests. As such, being on the path toward MOS or RAB does not mean that we cannot set in a new direction. We must utilize ‘priority triggers of change’ or boosters of transformative processes to move away from business as usual. The report identifies four key policy triggers: institutions and governance; consumer awareness; income and wealth distribution; and innovative technologies and approaches.

Following a systemic logic, changes made through these triggers within the agri-food system should also impact socioeconomic and environmental systems. Activation or deactivation of these triggers (especially regarding which stakeholders gain the power to influence the manner of their activation) will highly influence the realisation of certain scenarios. For instance, better institution and governance mechanisms will influence on a range of key drivers and domains, such as better institution and governance mechanisms will influence on a range of key drivers and domains, such as governance of new technologies, migration, market power and intergenerational equity.

The report concludes with the words of Antonio Gramsci, Italian philosopher and radical journalist. “My mind is pessimistic, but my will is optimistic. Whatever the situation, I imagine the worst that could happen in order to summon up all my reserves and will power to overcome every obstacle”: words to be taken to heart. Acceptance of long-term perspectives by citizens and their governments is crucial for transformative action to start now. We must ‘outsmart’ political-economic constraints and enlarge agency space.

As Foresight4Food, we are committed to promoting and enhancing foresight approaches to strategically prepare for different food systems outlooks, by learning from the past but especially looking forward to explore.